Children are inquisitive. Often, even happy endings of fairy tales do not satisfy them — they keep wondering, ‘And what happened next?' When they see a portrait of a child, they ask, ‘What happened next to this boy (or girl)?' We are going to speak of what became of the young characters of famous artistic works. Most of them lived a fortunate, or at least bright, life. Arthive has selected some child portraits of different time periods and arranged them chronologically.

Self-portrait at the age of 13

1484, 27.5×19.6 cm

‘Self-Portrait at the age of 13’

The thirteen-year-old boy in the silverpoint drawing is the one who drew it. The great Albrecht Dürer (1471—1528) was a pioneer in a lot of fields. His life was remarkably rich in events and accomplishments — thus, there is every reason to call it happy. To start with, none other than Dürer was the first Western artist who painted self-portraits. Later, he became the first artist who wrote an autobiography. And this drawing is Dürer's first known self-portrait.Some critics believe that he drew himself because he wished to observe how his looks were changing. That is why he started as early as possible.

In the nearly sixty years of his life, Dürer got fame not only as an artist, but as a geometrician, art theorist, mechanic, and architect as well. Perhaps, the only sphere he failed in was his married life. Sadly, there was much chill between him and his wife, as attested by his contemporaries, and the couple had no children.

Portrait of Giovanni Medici in childhood

1545, 45×58 cm

The happy kid

The portrait of a jolly little boy holding a goldfinch was a complete revolution in then painting. The artist Agnolo Bronzino in his oil on panel painting featured a chubby baby laughing — not a mannered aristocrat, a miniature copy of an adult, as young descendants of the nobility were then traditionally portrayed. And the boy in the portrait is none other than Giovanni de' Medici (1543—1562), the second son of Cosimo I, Duke of Florence, Grand Duke of Tuscany, and Eleanor Álvarez de Toledo. The painter broke with even more traditions: Medici is only shown half length, with his face seen almost exactly from the front, not in a classical three quarter view.In the Renaissance centuries, the portrait was often referred to as the happiest and prettiest likeness of a child.

So, what future awaited the infant so high in rank and title? In the picture, there is an indication of what he was supposed to become. The bird in his hand — a goldfinch — is a Catholic symbol of Christ’s Resurrection. In this way, Agnolo Bronzino hinted at young Medici’s future cardinalship — in those days, a ruler’s second son was to be trained for a career as a clergyman.

At the age of only fifteen, Giovanni de' Medici did become a cardinal. His office, though, did not prevent him from being fond of hunting and collecting antique statues. Unfortunately, he did not live long. Being only nineteen, he died in his father’s arms. His contemporaries suspected Giovanni’s younger brother in poisoning him.

Portrait of the Infanta Margarita in a pink dress

1654, 128.5×100 cm

The best-known girl of Spain

Diego Velázquez eternalised Infanta Margarita (1651—1673). The great artist painted six portraits of the little princess, who would become Holy Roman Empress, German Queen, Archduchess of Austria, and Queen of Hungary and Bohemia. Up to now, artists and poets find inspiration in her image.However, her image has been far luckier than the girl herself, in her real life. Nevertheless, she had something that not every royal descendant of those days could boast of. Infanta Margarita’s marriage was a most happy one. Indeed, she was adored by her husband, Emperor Leopold I (it was him most of Margarita’s portraits were painted for), and she loved him as much. They had similar tastes, and both of them loved art. For Leopold, she was his ‘only Margareta.' But think how unlikely it was that it would be a love match: the marriage was a matter of agreement when the girl was born. It is not a common thing that one loves when they are ordered to love. The life of the most famous Spanish girl was brightened with happy love — but, unfortunately, she only lived twenty-two years. Margarita had been a sickly girl since her childhood, and her delicate organism broke down after numerous childbirths (during the six years of her married life, the Infanta had four children).

Portrait of Sarah Eleonora Fermor

1750, 114×138 cm

‘The faithful spouse and the virtuous mother’

In a Rococo painting, Ivan Vishnyakov portrayed a ten-year-old countess Sarah Eleonora Fermor (1740—1824). The work is one of the most celebrated pictures that appeared in Empress Elizabeth Petrovna’s reign. The texture of the fabric the young countess’s dress is made of is painted so scrupulously that modern English experts were even able to identify a sample of silk produced in England on the basis of French patterns in the middle of the 18th century.To return, however, to the portrait. The ten-year-old girl follows the ways of adult people in everything. She has assumed the right posture, doing her best to remain upright in her corset, holding her fan in a manner prescribed by etiquette, and smiling with a proper ‘society' smile. And to think that young Sarah had to be posing for hours and hours! Her patience would be amply rewarded: not only would the girl’s portrait painted by Vishnyakov get fame, but the girl herself would live a long and happy life.

Countess Sarah Fermor, the daughter of General William Fermor, a Russianised Scotsman, got married at the age of twenty — quite late, by the standards of that time. Her husband was her peer, Jakob Pontus Stenbock. According to some sources, Sarah Eleonora had nine children. In Tallinn (then Reval), the couple had a family palace, which is now used as the official seat of the Estonian government. It houses the prime minister’s and other statesmen’s offices.

Portrait of Alexander Alexandrovich Chelishchev

1809, 48×38 cm

The first Romanticist

In 1809, Orest Kiprensky showed the public the portrait of twelve-year-old Alexander Chelishchev (1797—1881). The moment it was presented, the picture became popular. It opened the era of Romantic portraits in Russian painting.Kiprensky portrayed a boy who was to become a cadet at the military academy called Corps des Pages — the Page Corps. Perhaps, for the first time in the Russian artistic tradition, the painter did nothing to make his model look older, closer to the adult world. On the contrary, the person we can see in the picture is a boy, indeed, with eyes beaming with childish simplicity and innocence. However, the colours — the dark jacket, the white collar of the shirt, not clearly seen, and the scarlet waistcoat — create an air of mystique about the character.

The character’s life was long, and it never lacked romanticity. In 1812, he took part in the war. With the Army of Silesia, he ended up in Paris and was honoured with a number of decorations for bravery under fire. Later, he joined a secret political society of the future Decembrists, but took no part in the revolt itself. Following his retirement from the service, at the age of thirty-six, he married Alexandre Pushkin’s distant relation and made a loyal landowner. The couple had four children. Chelishchev lived retired for almost half a century, and found pleasure in ‘talking of old times, of the days of their pride, and the fights where together they struck side by side.' He, who once was a romantic boy, had his share both of storms of life and of peace — is that not real happiness?

Portrait of the artist's children

1882, 192×82 cm

Children of the artist

The most expensive Russian artist of the late 19th century, Konstantin Makovsky, was greedily sought after. He was a court painter famed far beyond the Russian Empire . None other than him was the first to be invited to portray Theodore Roosevelt as President. And besides, the artist managed to find time to paint children, including his own ones, whom he had nine, from his three wives.The best-known are the portraits of his son Sergey (1877—1962) and daughter Elena (1878—1967). In the picture, Seryozha is wearing long hair. In those days, many artists did not allow cutting their little sons' hair short, as long tresses made a fine contrast to their juvenile delicacy (Renoir, too, portrayed his son long-haired — see below). And the children’s portrait that got the most fame is called by that name — Children of the Artist. It features Lena and Seryozha together. The two charming little ones in a garden — the two flowers amidst flowers.

Later, these two, Elena and Sergey, became the most famous of Makovsky’s children. In 1920, Sergey emigrated to Prague, and then to Paris. His education was excellent, and he became an art critic and poet. Sergey’s friend Nikolay Gumilyov spoke highly of his verse and dedicated to him the poem I thought, I believed. Makovsky wrote five monographs on visual and applied art, and the sixth one was on art criticism.

Elena Makovskaya emigrated to the German Empire (it was the country’s name then), where she became highly popular as a painter. She married the Viennese sculptor Richard Luksch and had three children: two sons and a daughter. A statue by Luksch-Makovskaya (also spelt as Luksch-Makowsky), Woman’s Fate, is one of the pieces still gracing a park in Hamburg. And a picture by her is exhibited in the Belvedere Palace, beside Gustav Klimt’s works.

Mika Morozov. Portrait of Mikhail Mikhailovich Morozov

1901, 62.3×70.6 cm

Who can tell by his features he will be a Shakespearean scholar?

The best-known portrait of a child painted by Valentin Serov is perhaps that of Mika Morozov. The four-year-old boy was a son of Mikhail Morozov, a merchant, patron of arts, and art collector, and Margarita Morozova (née Mamontova), a prominent figure in Russian cultural, religious, and philosophical education in the early 20th century. Mika disliked posing, so Serov had to paint his model in a series of short sittings, each lasting not more than twenty minutes.Mika (short for Mikhail) Morozov (1897—1952) started being taught English when he was two years old. Later, he studied in Great Britain, then returned to Russia and received education at the Faculty of Philology of Moscow State University. Mikhail Morozov became a reputable literary scholar, theatre theorist, teacher, and a founder of Soviet Shakespearean science.

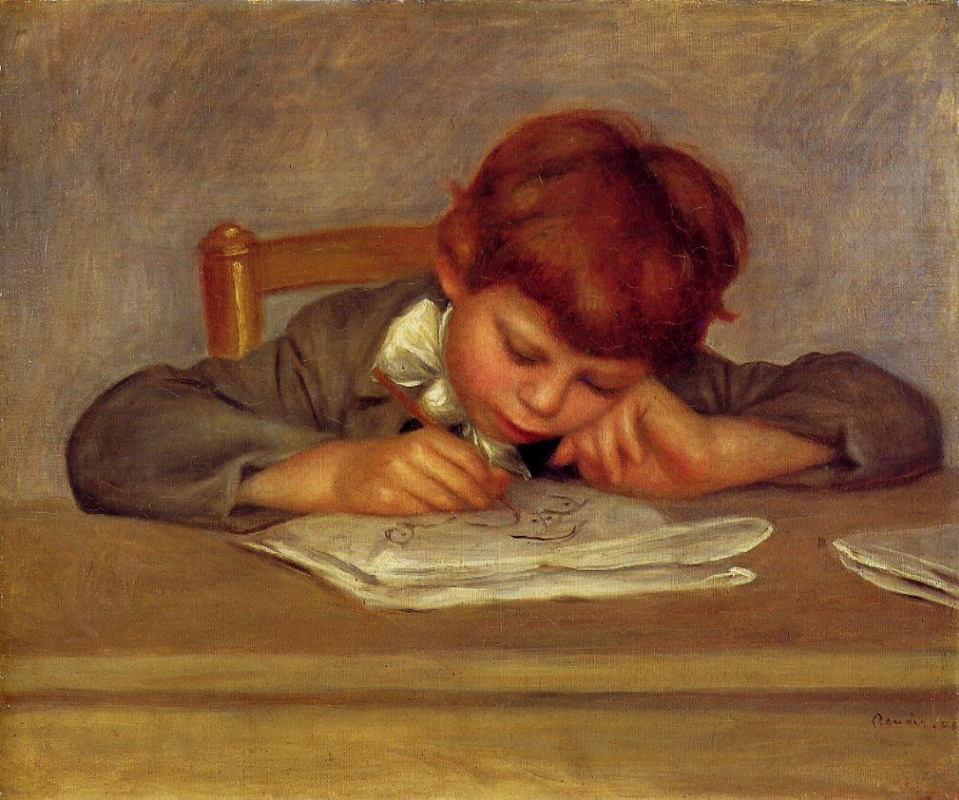

The great father’s great son

Pierre-Auguste Renoir, one of those who started French Impressionism , was said to be an artist ‘who never painted a sad picture.' He enriched the world with a good deal of children’s portraits. His own kids were his favourite models.Auguste Renoir was quite a crazy dad. To keep his little son Jean quiet for a half-hour sitting in his father’s studio, the boy was read aloud Andersen’s fairy tales. Jean was not a pretty boy, but his hair seemed to be real gold. The hair of Renoir’s sons was kept long for two reasons: to protect their heads against falls, and to provide Renoir with an inspiring opportunity to paint more golden glistening on the children’s locks. Jean only bid farewell to his hair when his younger brother was born.

Jean Renoir sewing

1900, 55×46 cm

Auguste Renoir and his wife Aline had three children: Pierre, Jean, and Claude. All of them engaged themselves in art, somehow or other. The youngest, Claude, became a ceramic artist, the eldest, Pierre, a talented actor, the middle child, Jean, a film director.

Jean Renoir’s (1894—1979) oeuvre refutes the popular belief that the mother nature rests from labour for children of geniuses. There are art lovers who consider that not Jean is the great father’s son, but Pierre Auguste is the great son’s father.

Jean Renoir made the greatest pre-war French film, The Grand Illusion (1937). There are no battle-scenes, and only one character perishes, yet The Grand Illusion is still regarded as one of the most significant anti-war films. At the Venice Film Festival in 1937, the jury did not find courage to give it the Grand Jury Prize, so they awarded it for the Best Artistic Ensemble — a consolation prize, invented for the occasion.

In Germany, the Nazi Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels banned the film. He declared Renoir ‘Cinematic Public Enemy No. 1,' and called on his Italian colleague from Mussolini’s fascist government to do the same — and it was done. For a long time, all European prints of The Grand Illusion were believed to have been destroyed by the Nazis, but in 1945, in Munich, the Americans found its negative (paradoxically, it had been kept safe by none other than the Germans). The film was then restored and ranked fifth in the list of the twelve best films of all time.

In 1974, Jean Renoir got an Academy Award as ‘a genius who, with grace, responsibility and enviable devotion through silent film, sound film, feature, documentary and television, has won the world’s admiration.' It is hard to be certain about every person living on the Earth, but for every filmmaker, this award is, no doubt, equivalent to HAPPINESS.

Jean Renoir’s (1894—1979) oeuvre refutes the popular belief that the mother nature rests from labour for children of geniuses. There are art lovers who consider that not Jean is the great father’s son, but Pierre Auguste is the great son’s father.

Jean Renoir made the greatest pre-war French film, The Grand Illusion (1937). There are no battle-scenes, and only one character perishes, yet The Grand Illusion is still regarded as one of the most significant anti-war films. At the Venice Film Festival in 1937, the jury did not find courage to give it the Grand Jury Prize, so they awarded it for the Best Artistic Ensemble — a consolation prize, invented for the occasion.

In Germany, the Nazi Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels banned the film. He declared Renoir ‘Cinematic Public Enemy No. 1,' and called on his Italian colleague from Mussolini’s fascist government to do the same — and it was done. For a long time, all European prints of The Grand Illusion were believed to have been destroyed by the Nazis, but in 1945, in Munich, the Americans found its negative (paradoxically, it had been kept safe by none other than the Germans). The film was then restored and ranked fifth in the list of the twelve best films of all time.

In 1974, Jean Renoir got an Academy Award as ‘a genius who, with grace, responsibility and enviable devotion through silent film, sound film, feature, documentary and television, has won the world’s admiration.' It is hard to be certain about every person living on the Earth, but for every filmmaker, this award is, no doubt, equivalent to HAPPINESS.

Afterword

The first one who read this article was neither a child nor an adult, but fourteen-year-old Valery, a student of a Physics and Mathematics Lyceum.‘A curious tendency,' he remarked. ‘The lives described are only those of the nobility and of people who, later, themselves pursued an artistic career or studied humanities. But why so? How about the great mathematicians?'

‘Dürer practised geometry, and was quite good at it,' I retorted. ‘However, in essence, you’re right. The reason is simple, though. Firstly, a noble descendant’s life is easier to trace. And secondly, remember the old adage "Where there’s an apple on the ground there must be an apple-tree around." In other words, painters' children tend to become painters themselves rather than take up exact sciences.'

‘That's true,' agreed the young mathematician. ‘Still, I find it sort of unfair to those who love sciences.'