Engraving as a guarantee of independence

"…I shall stick to my engraving," wrote the upset 38-year-old Dürer in a letter to the merchant Jacob Heller in 1509. "And if I had done so before I should today be a richer man by 1,000 florins."A few years before that, the wealthy and haughty Heller commissioned Dürer to create an altarpiece for the Dominican church in Frankfurt, promising 200 florins as payment for it. That wasn’t much, Dürer's teacher Wolgemut would have jacked up the price five-fold, but the strapped Dürer had to agree. The work involved a lot of difficulties, the artist was exhausted because of that altar, had a fever, was tormented by the problems regarding composition and color. Considering the fact that he spent half of the promised fee on an expensive blue pigment only, Dürer first asked, and then demanded to increase his payment, because, being completely occupied with the altar, he wasn’t able to do anything else! But the moneybag Heller was uncompromising: he wouldn’t pay him even a florin more, while Dürer had to think about finishing his work on time instead of looking for excuses. Who cared about his creative search, when the money had been paid in advance?

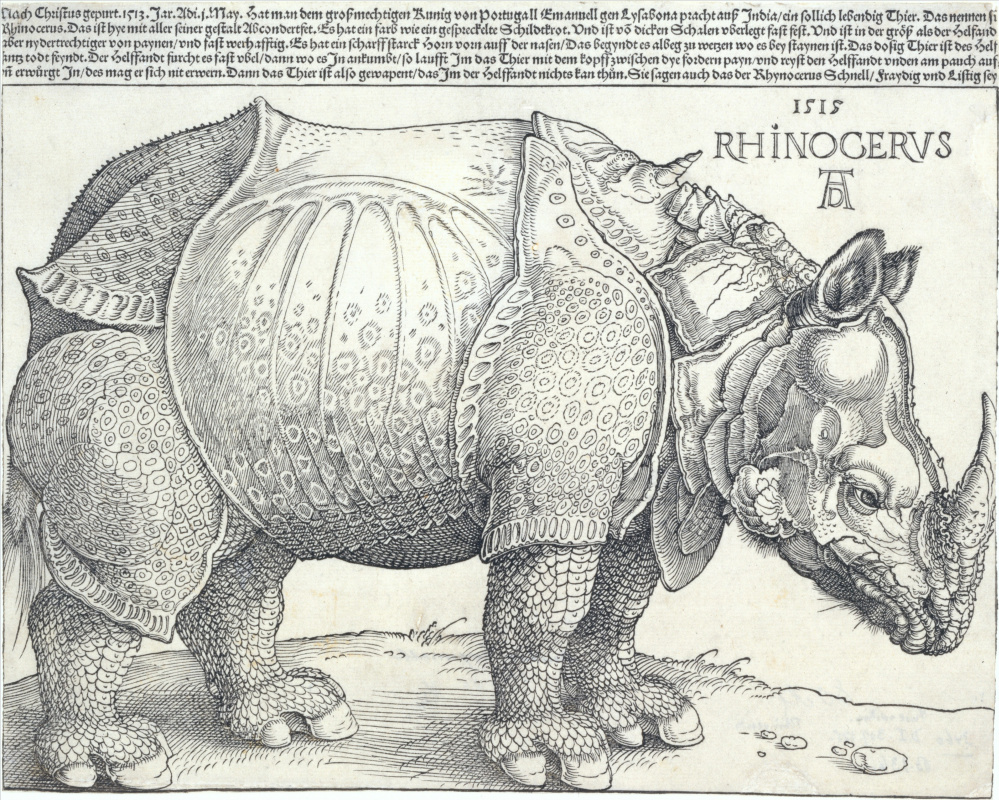

Engravings once again became the artist’s salvation in a desperate situation when he was morally exhausted and financially desperate. Paintings always had their commissioners — a merchant, a patrician, a monastery, a monarch — and that often limited the artist in choosing means. When it came to engraving, Dürer was free to do anything that was interesting to him. Sometimes a painting board or canvas cost more than a dissatisfied customer was willing to pay — but engravings printed in the large printing house of Dürer's godfather Anton Koberger enjoyed mass circulation and brought in a big revenue. A painting in a single copy can make you known to a narrow circle of connoisseurs, hence only the lucky ones will see it. Engraving , accessible even to the poor, is a nationwide recognition and fame that will quickly cross the borders of Germany.

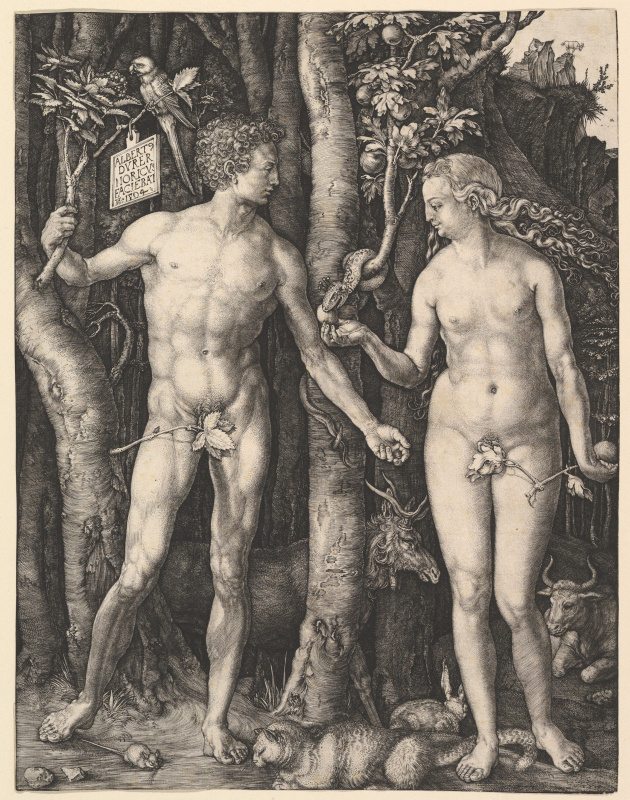

Painting (in Dürer's case) is risky and difficult experiments. Engraving is money, fame and independence. And while Dürer had countless rivals in painting, he was second to none in Europe when it came to engraving. This what Erasmus of Rotterdam said about Dürer as an engraver: "He needs only two colors to convey all the splendor of the visible world."

Apocalypse today

In the year before Dürer's birth, his godfather Anton Koberger established a printing house in Nuremberg. It was the second printing house in the city — the first one was established shortly before that by Johann Sensenschmidt. His enterprise went so well that Koberger, who, like Dürer's father, was a skilled jeweler, abandoned his "gold and silver craftsmanship" and spent his savings on the purchase of printing presses. Quite soon, Nuremberg became one of Europe’s largest publishing centers. Vladimir Vernadsky wrote: "Nuremberg's printers were distinguished by their entrepreneurial spirit, they took orders from distant cities: for example, they printed books at the expense of Polish scientists and amateurs long before the opening of the first printing houses in the Kingdom of Poland. They also made and cast letters for the first Russian books of the late 15th- early 16th centuries, which were published in Kraków and Prague."Koberger’s printing house became the largest in Germany; more than a hundred people worked on 24 presses at the peak of the company’s activity. Of course, the young Dürer often visited his godfather’s estate. He smelled fresh printing ink, learned to handle a heavy press and examined numerous engravings which mainly served as book illustrations back in those days. Dürer saw woodcarvers at work — xylography was very popular in Germany. He could examine the artists' manner from its different sides.

Dürer learned the art of metal engraving from his father, who believed that his son would continue the jewelry dynasty; moreover, Nuremberg carved dishes, goblets, and jewelry collet setting were highly valued in Europe. When Albrecht decided to become an artist instead of a jeweler, it really shocked his father. It was the "apostate" Koberger who managed to convince his friend to let his son become an apprentice in the shop of the painter Michael Wolgemut and even paid half of its cost: if Albrecht had failed to become a painter, he would have been able to engrave illustrations for the books of the Koberger printing house.

After finishing his studies under Wolgemut, Dürer, as befits any beginner artist, went on a "pilgrimage". In Italy, he had to prove to local artists that he was skilled not only in drawing (hand steadiness and the perfect eye-sight are the most important qualities of an engraver), but also in paints. Dürer, in turn, was surprised that the Italians paid so little attention to engraving — only Mantegna was really interested in it. Dürer copied his engravings for educational purposes.

And that’s when Dürer experienced a real "insight" - a kind of mystical enlightenment, when you inevitably understand what you have to do next. Being deeply and passionately religious, Dürer re-read the Revelation of Saint John the Theologian many times and realized: that was exactly what he had to depict. The end of the world and the final judgment, four horsemen of the Apocalypse and the Wormwood star, a "woman clothed with the sun" and Saint John devouring a book, a vision of seven candlesticks and the Archangel fighting a dragon … 16 large-format woodcuts, each of which has a verse from the Apocalypse printed on its back. Dürer worked on them very quickly, feeling that an invisible hand was leading him. The woodcuts of the Apocalypse series cut by the best carvers and printed in the Koberger printing house were sold at the market fairs by Dürer's wife Agnes or his mother Barbara. Neurotised by the approaching doomsday, the townspeople bought them up instantly. Merchants brought the woodcuts of the Apocalypse series abroad as the most popular goods. On the part of the author, it was hitting the bull’s eye, or as they would say now, a real "hype".

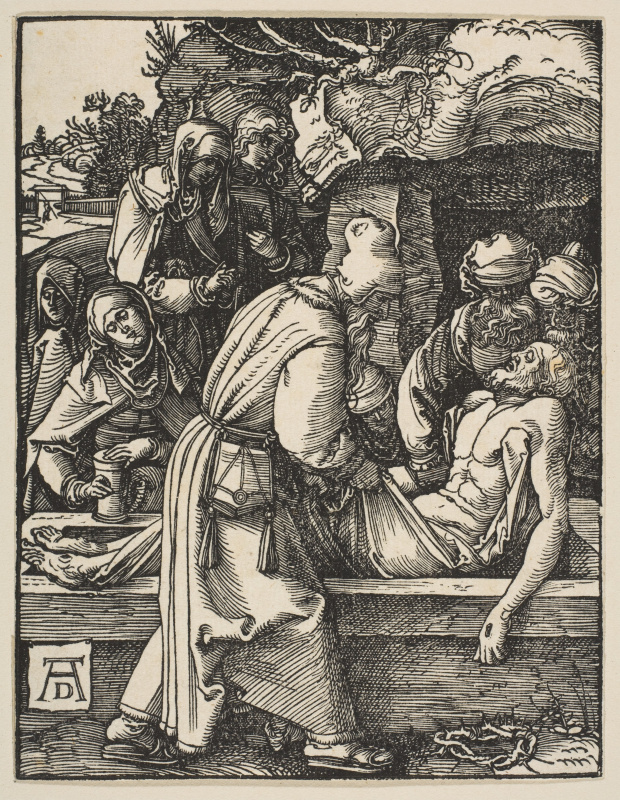

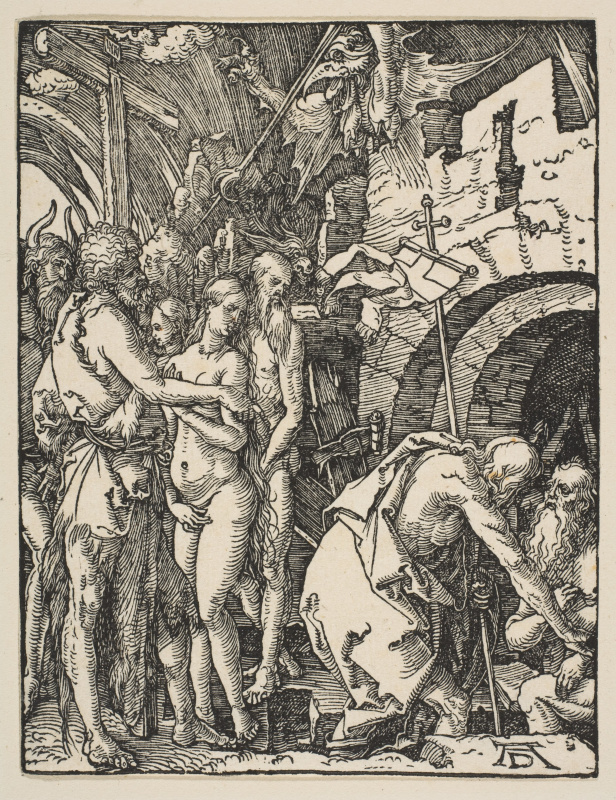

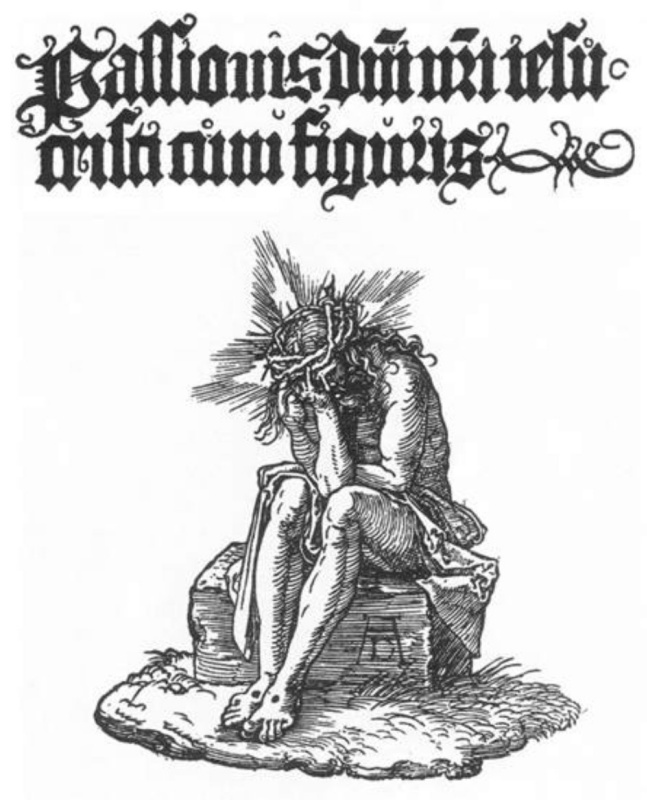

"Passion" – large, small, green and other

While the Apocalypse was created at once (or, as contemporaries said, "whispered by angels"), Dürer was working on the theme of the last days of the Savior’s earthly life ("passion") back and forth. He came back to his Passion in various states of mind, tried using different formats and techniques. However, his interest was not unique: Gospel descriptions of the torment of Jesus Christ are generally the leitmotif of the art of the 15th century. But Dürer, solving the most complex plastic problems, brought real sophistication to the topic, which was well studied by other artists.Dürer has several cycles of Passion. In 1511, he published a series of 11 woodcuts, called The Large Passion (the number of prints varies from 11 to 15, depending on the source). At the same time, the artist worked on the engravings on the same topic, but on small boards — it’s the so-called Small Passion series, consisting of 36 woodcuts. Since about 1507, Dürer performed similar plots not only on wood, but also on copper — these engravings got the name Passion.

There is also the unusual term "Green Passion". It’s used to refer not to the engravings themselves, but to Dürer's preliminary drawings. They are distinguished by great dramatic power and artistic value. "This unique technique consists in combining a pen and a brush against a green background, which gives the bright places of the picture a powerful dramatic shade, some kind of supernatural glow," explains Marcel Brion.

Christ before Caiaphas. Pen drawing on green primed paper. 1504, Albretina, Vienna.

Albrecht Dürer's Mary

Perhaps the most popular topic among ordinary people (the main buyers of Dürer's woodcuts) was not his Apocalypse, not the Passion, and certainly not the intellectuals' joy — his skilful engravings. Dürer's most popular engravings were those about the life of the Virgin Mary (Dürer created a cycle of the same name in 1511, and also made individual engravings on the subject in different years). Here the elderly Joachim and Anne stand embracing: childlessness makes them look ignominious in the eyes of their compatriots and they pray to be blessed with a child. And here the angel tells Joachim: you will have a daughter. Here the girl is brought to the Temple. And here Anne is looking at the already adult Mary, who gave birth to a Son … What was not in the Gospels was broadly described in the apocryphal literature (for example, "The Golden Legend" by Jacob Voraginsky), and Dürer used those subjects. Just like some modern "real-life" series, Life of the Virgin met all the hidden sentimental aspirations of the viewers.Wood engraving and copper engraving: what's the difference?

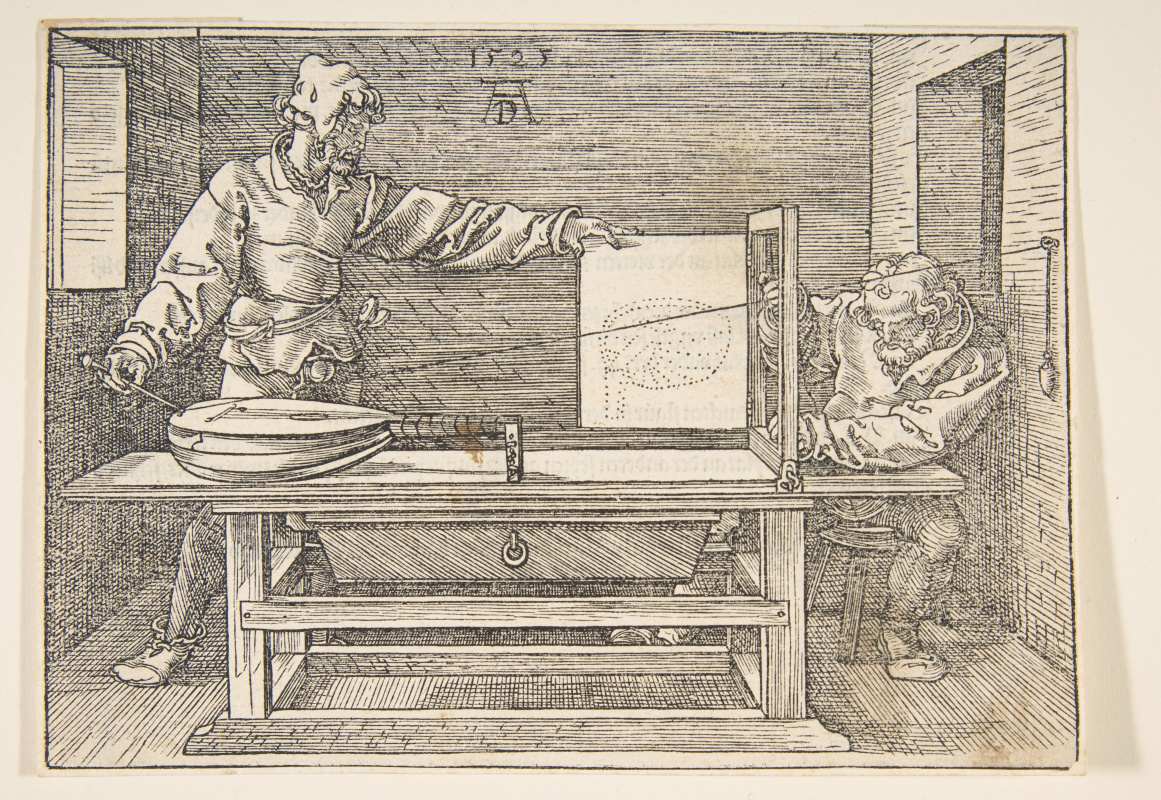

At the time of Dürer, there existed two main engraving techniques — wood engraving and copper engraving , xylography and calcography (from the Greek. ξύλον - wood, χαλκός - copper and γράφω - I write). Usually, artists specialized in one of the techniques, but Dürer was the only one who equally mastered both.The procedures of making wood and copper engravings are essentially the opposite. In both cases, it all starts with a drawing created by the artist. Then carvers come into play — and their actions vary depending on the material chosen. If the matrix with the drawing is wooden, then the cutter begins to deepen the unfilled spaces around the image. Thus, the contours become raised, and the background is deepened. A print from such a matrix is called a letterpress technique. Working with a metal plate, a cutter uses a graver directly on the drawing. The image deepens, while the background remains intact. This is an intaglio printing technique.

It is clear that working on metal, you can get much more differentiated and thin strokes, which means much more detailed images. At the same time, woodcuts have their own advantages and their own aesthetics — their strokes are more powerful, more expressive. Woodcuts are very popular among the general public, while calcography is often engravings for connoisseurs and intellectuals.

It is difficult (if not impossible) to imagine, for example, Dürer's Melencholia I performed on wood: such sharpness of the image and the fineness of strokes can be achieved only on metal. At the same time, the graphic expression of the Apocalypse requires a soft and compliant wood panel.

Making his woodcuts, Dürer used the services of highly professional carvers. However, he always applied drawings to copper plates himself.

The advantage of letterpress printing was that it was possible to make more prints from a wooden matrix — up to a thousand, while a copper matrix usually made it possible to create only about two hundred copies without a complete loss of "sharpness". Thus, copper engravings were more expensive.

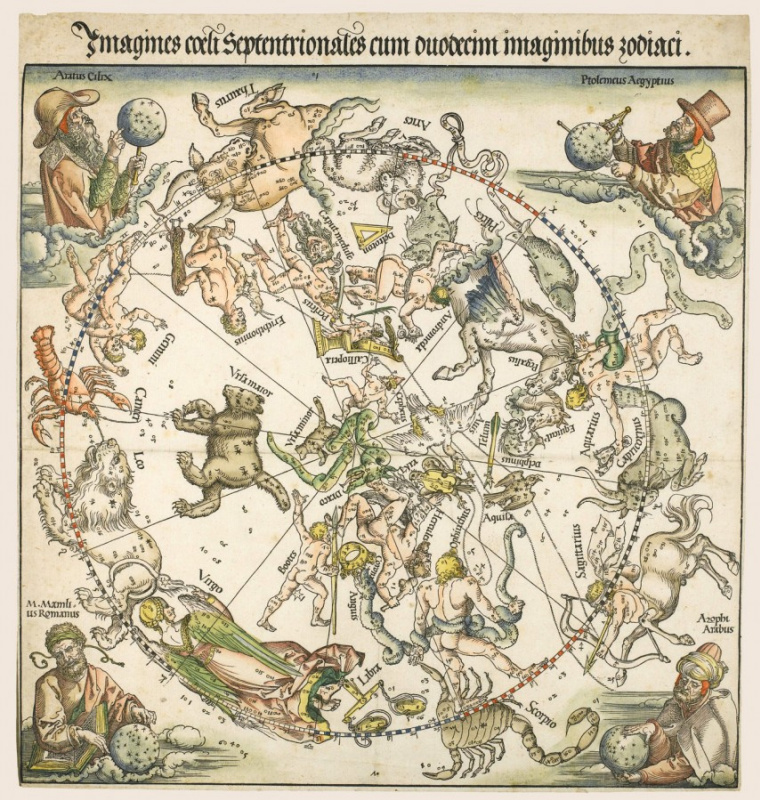

"Dürer was interested in geometry and the theory of perspective, tried his hand at cartography, left a noticeable mark on the history of astronomy, was engaged in the construction of scientific instruments. Many of Dürer's drawings and engravings can be considered as monuments of science of his time," wrote Galina Matvievskaya in her book "Dürer The Scientist".

Naming, branding, copyright

Dürer is rightly called the main artist of the German Renaissance due to his creative universality (painter, graphic artist, scientist), but not only because of that. He had a stable author’s identity that fundamentally distinguishes him from medieval masters. No wonder that Dürer became the first woodcut artist to systematically sign his engravings.Actually, naming — the composition of the original name of the brand — was conducted by Albrecht Dürer the Elder, a Nuremberg jeweler and Dürer's father. As it is known, he was a Hungarian immigrant whose last name was not Dürer at all. Here’s what the son wrote about his father’s origin in the autobiography: "Albrecht Dürer was born in the Kingdom of Hungary, near the small town of Gyula, in a village called Ajtós, and his family earned their living by breeding bulls and horses." The original surname of Dürer's ancestors was Ajtósi. "Ajtós" is "doormaker" in Hungarian (from "ajtó", meaning door). In German, the "door" is "die Tür". After moving to Germany, father Albrecht Ajtósi changed his "door" surname so it sounded more German. At first, it became Türer, but later turned into Dürer, to adapt to the local Nuremberg dialect.

To make the name a brand, the son invented the "logo" for it — he signed his engravings with the letters A and D (his initials) in a unique way — A was depicted as a doorway.

This engraving from the Metropolitan Museum of Art (illustration above) is an image of the family coat of arms of the Dürers. It includes not only Dürer's signature itself (above, on the scroll), but also its prototype — an open door. The same one was depicted on the sign of the jewelry workshop of Dürer the Elder.

Copyright case

Dürer's success (both creative and commercial) caused a surge of interest in engraving in Germany, Flanders and Italy. Many artists began to engrave their own and other people’s works, and Dürer served as a model for them — variations on his plastic solutions were created, for example, by Lucas Cranach. However, many of them quickly realized that creating something original is longer and more expensive than faking other people’s "hits". Across Europe, artisans of various skill levels began to create "pirate copies" of Dürer's prints. And, despite the fact that counterfeits often came out rather rough, fakes were sold like hot cakes — after all, they were decorated with the Dürer's famous "logo".Once Dürer got a small engraving from his Passion cycle from Venice. He immediately recognized the fake. The copy was made skillfully! But Dürer's original work was a woodcut, while the carver for some reason decided to repeat the same on copper, which gave him the opportunity to add new and interesting small details. Yet, the "counterfeiter" decided to leave Dürer's "logo" unchanged. In a letter, Dürer was informed that the plagiarist’s name was Marcantonio, who was a Bolognese by origin. "He flew into such a rage that he left Flanders and went to Venice, where he appeared before the Signoria and laid a complaint against Marcantonio," wrote Vasari.

And here’s probably the most unusual way of using engravings. Emperor Maximilian commissioned a monument glorifying his wisdom and greatness — a triumphal arch three and a half meters wide, consisting of 192 wooden blocks with engravings. The best minds of Germany (including Dürer's friend Pirckheimer, who was a humanist) worked on the program of the arch, i.e. those feats of the emperor and his ancestors, which had to be immortalized, and their allegorical interpretations. Dürer took part in the creation of engravings, although he understood that it was plain impossible to achieve at least some integrity of impression in such a monstrous structure.

Master prints

After lengthy experiments with engraving , Dürer switched to a new technique: he began using a dry needle instead of a cutter. The finest needle with a steel or diamond tip glided so easily over the surface of the copper that it was more convenient for the artist to hold the brush motionless by rotating a metal plate under it. If you look at such work under a magnifying glass, you can see the burrs on the sides of its contour — the so-called "barbs". Thanks to these barbs, the contour loses its rigidity, while the strokes become flexible and the lines seem to vibrate. Three engravings with complex symbols, created in this, without exaggeration, unique technique, are called master prints.The engravings Knight, Death and the Devil, St. Jerome in His Study and the famous Melencolia I were created by Albrecht Dürer in 1513−1514. And despite the fact that the relation between their plots is far from being obvious, the works still make up a kind of an "engraving triptych." These are the master’s top works.

Though Erasmus of Rotterdam was essentially right when stating that Dürer embodied all the splendour of the world only in two colours, he wasn’t entirely accurate.