Germany’s Weimar Republic was established between the end of World War I and the Nazi rise to power. A thriving laboratory of artistic and cultural innovation, it documented the social tension, political struggle and turmoil after the violent and bitter war conflict. The country’s unprecedented upheaval impelled many artists to reject Expressionism in favor of a new realism to capture the new emerging society.

This new art movement, now known as Neue Sachlichkeit—New Objectivity—was also termed as 'magic realism' by the artist and critic Franz Roh in 1925 and demonstrated a transition from the anxious and emotional art of the Expressionism towards the cold veracity and unsettling imagery of the inter-war period. This new realism reflected more liberal society and moral depravity and decadence in the context of the economic collapse and growing political extremism.

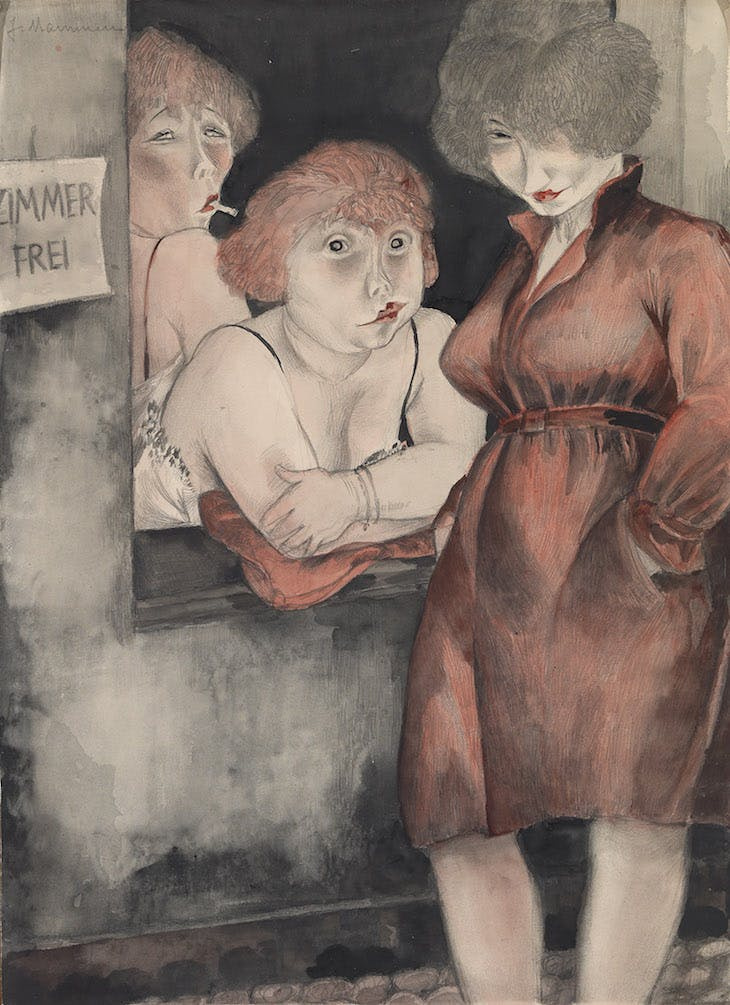

It was a very strange and chaotic time. Roving gangs of Communists, Anarchists, Pro-Republics, and right-wing Nazi SA stormtroopers were so passionate in their competition for government control that they battled each other right in the streets. The treaty of Versailles, and later the Great Depression, produced inflation, making German currency worthless. Many people went broke and they were pulling in tricks to make ends meet. As a result, crime and prostitution grew. During this time, police identified 62 organized criminal gangs operating inside Berlin.

The display showcases a watercolor by Rudolf Schlichter The Artist with Two Hanged Women, a dismal 1924 drawing portraying the artist who sits and contemplates two dead women in high button shoes hanging from his ceiling. Schlichter, the Dadaist and the New Objectivist, did like when his wife wore such boots, for which he displayed a marked fetish. And the artist has actually photographed his wife hanging from the ceiling in these shoes when holding the other end of the rope. This weird photo is not displayed at the show, thank goodness.

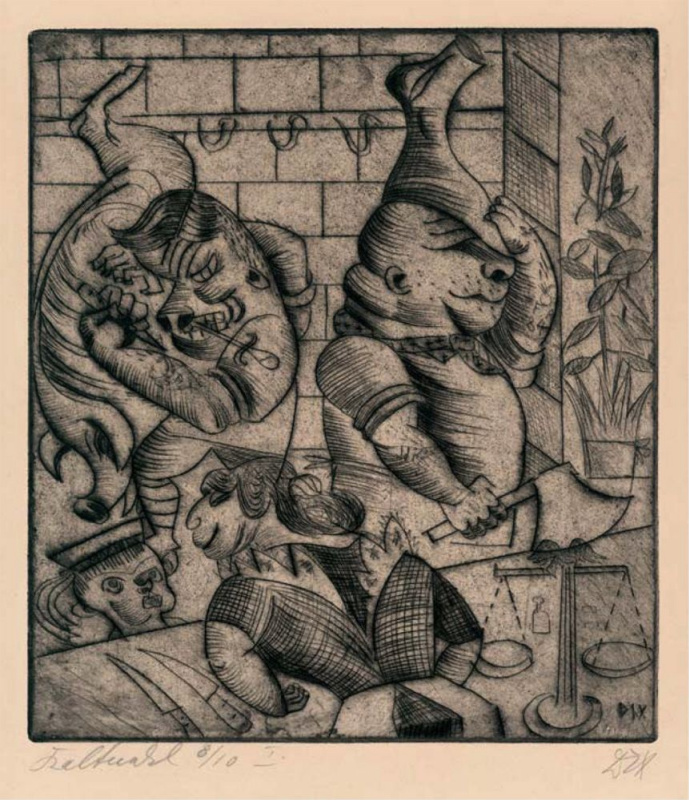

Lustmord theme continues in two works from 1920 and 1922 by Otto Dix at the exhibition, both entitled Lust Murderer. One depicts a killer dancing with the leg of his still-spurting, dismembered victim. These etchings are even more astonishing.

Maria Tatar, an expert in art of the Weimar era, in her book "Lustmord: Sexual Murder in Weimar Germany" quotes Dix’s explanation of why he painted murdered prostitutes: "I just had to get it out of me."

She traces much of Weimar’s "gender trouble" to Germany’s unprecedented defeat in World War I. She says that in the 1920s, German males felt emasculated by their military subjugation and invented a "stab in the back" theory to explain it. She writes: "The rank-and-file soldiers positioned themselves as victims or martyrs who sacrificed for the fatherland and then were betrayed by the women who stayed home and supposedly took over the labor force. Women became the enemy. You repair the trauma by killing the feminine."

Just add here the fact that women in Germany were granted the right to vote in 1918 and as a result, their emancipation gathered pace during the Weimar era. All these reasons may well explain why the sexually motivated murder of women was a weirdly prevalent theme in male artists' fantasies in 1920s.

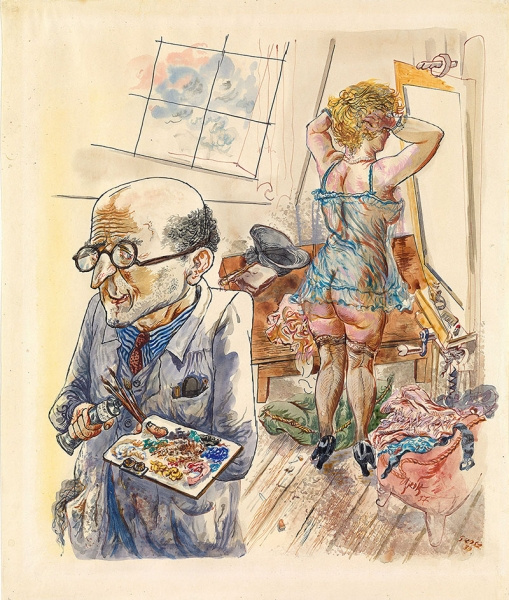

The representation of women is a recurring subject at the exhibition. Aside from pictures of prostitutes and violent attitude towards women, there are several portraits that depict women of a new era, with cropped hair, emancipated glance, full of confidence and self-esteem. Moon Women by Otto Rudolf Schatz were recognized by contemporary reviewers as works "from the margins of society, most concise." First shown by Schatz under the title "Girls in a Landscape," they created a shock effect on critics "with two rigid and cheerless female nudes, who looked like unclothed store window mannequins." The strikingly new and avant-garde approach evident in these female nudes combined Surrealism and New Objectivity. The naked female bathers wearing only shoes with their hands behind their back remind us more of businessmen dressed in suits that look straight into our eyes without any sings of shame or confusion as if telling us: "Nothing personal just business."

Left: Otto Rudolf Schatz, Moon Women. 1930. The George Economou Collection

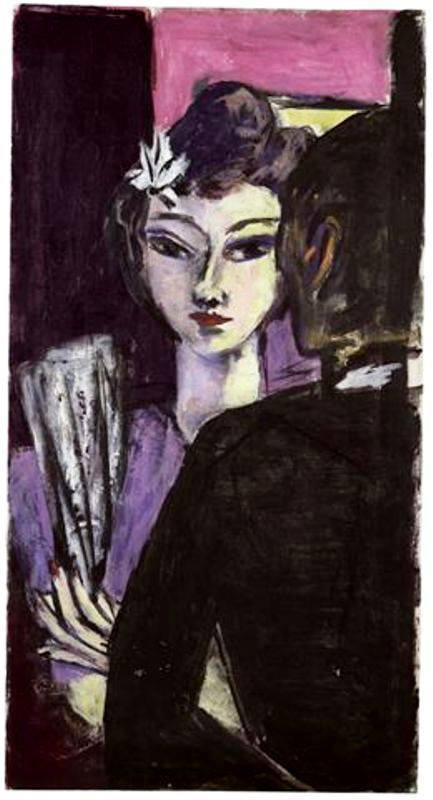

Cabaret and circus performers interested Dix and other artists as a subject because they lived on the fringes of society, free from moral constraints but subject to great personal danger. Artists felt great sympathy for them on the one hand, but being afraid of their aggressiveness and fantastic openness to sexual experiments, they distorted performers' traits making them look more like wild-beasts, on the other. Otto Dix’s pints at the show include images of trick riders, a tattooed lady, and an animal tamer which is dressed like a dominatrix, whose stubby features resemble a lion’s muzzle.

Left: Otto Dix, Lion-Tamer. 1922. The George Economou Collection

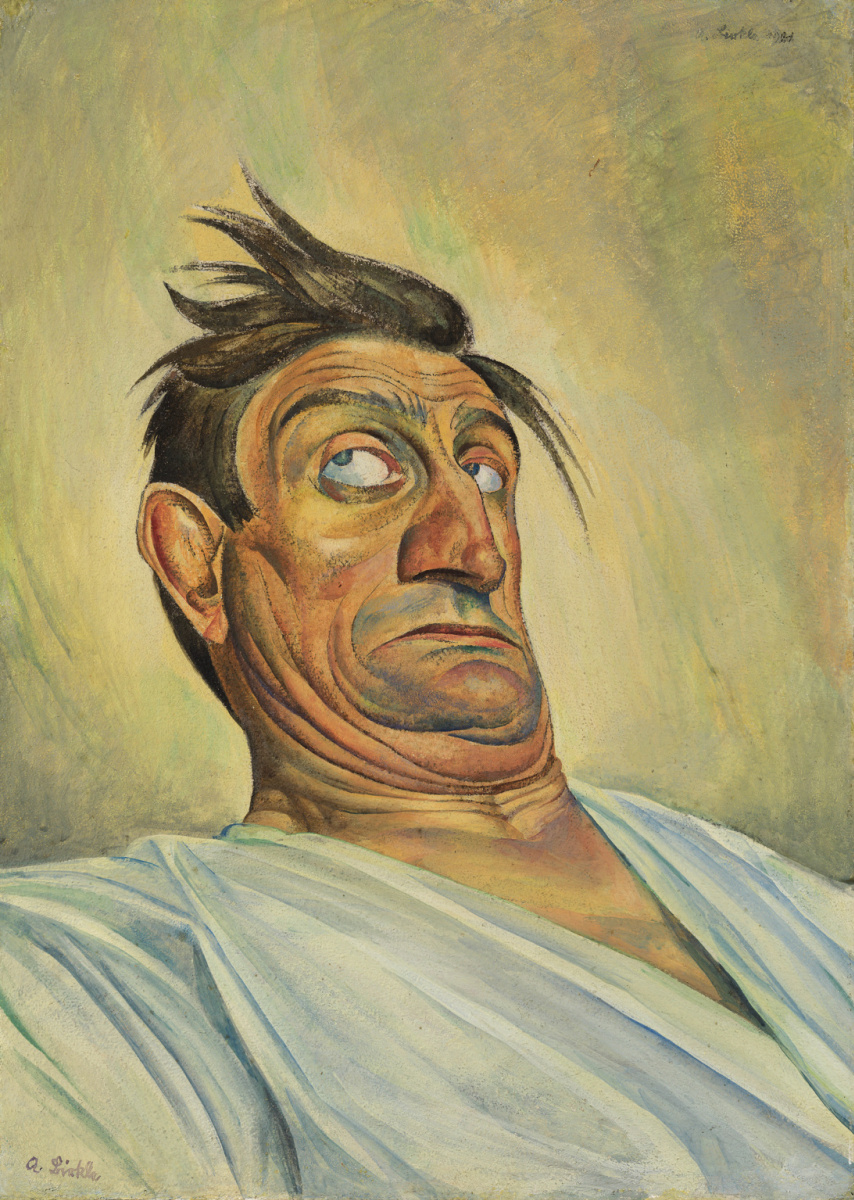

But who were those daredevils? Just look at Schulz, one of them. He’s a middle-aged man, his skin is flabby and wrinkled. He is staggering backwards and rolling his eyes upwards in bewilderment. Is there someone falling from the ceiling? Birkle does not show any action taken from his part, just his emotion. In his portrait, we see not only a shabby man, unsure how to react and what to do, but the whole German nation in a perplexed era of Weimar Republic.

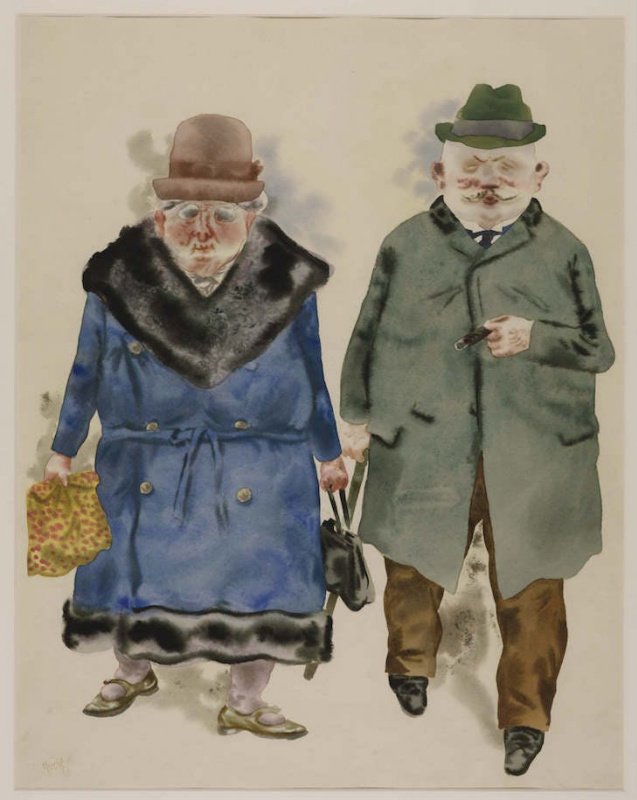

During the war, Grosz, along with his friend John Heartfield, began making the Dada anti-war art. After the war, he produced savagely satirical paintings and drawings that "expressed [his] despair, hate and disillusionment." He became a New Objectivity artist who examined the Weimar Republic’s desperate and wretched marginals, like wounded soldiers and prostitutes, and criticized politicians and profiteers.

As one critic put it, referring to the New Objectivity movement, painting like Grosz’s was "not likely to be acceptable to those who want art to be pretty". The same refers to all artworks exhibited in the Magic Realism . Don’t wander into the display in search of "pretty". It’s characterized by an unflattering realism and intense emotionalism that prompts us today to think where we were, where we are now and in which direction we are moving.

The show is accompanied by a fully illustrated catalogue from Tate Publishing.