A curious fact: everyone knows the Venus symbol, but few know that the picture signifying femininity is derived from a pictorial representation of the hand mirror popular in the classical world. There are some indications that the sign of Venus’s looking-glass is traceable to the Ankh, the Ancient Egyptian symbol of life, understood as the key of life, the symbol of eternity.

The sombre mediaeval glance

In the Dark Ages, when Europe looked into the mirror, it was an apprehensive look.Indeed, is it any good when lay people, instead of praying, keep staring at themselves? Well, pride feeds best on self-admiration. What is more, pastime like this can make women (and men, too) desire something quite far from pure and spiritual. So, the Church and the authorities tried to curb their flock’s demands. Thus, they insisted that the mirror was nothing else, but a mere luxury, a companion of vanity and narcissism, and preached that, if misused, it could make a person mad. In categorical terms, the Church diabolised mirrors and demonised their owners. Those who experimented with mirrors were accused of sorcery. A general belief was that reflections in some surfaces could cleave not only the body and the heart, but the mind and will as well.

But is there a lady that would miss a chance to cast a glance at herself? That is why it became absolutely necessary to popularise the moral virtues, thus setting the careless lovely creatures on the right pass. So, for a long time, allegoric subjects took their place in the history of painting.

Bellini portrayed a wise girl who averted her face from the mirror: the devil was looking out of it!

Didactic illustrations were a job for a lot of painters. For example, Albrecht Dürer's student Hans Baldung Grien (c. 1484—1545) showed the brevity of time: a woman with a mirror and an hourglass, in the company of Death, was a popular motif.

No intimidation, though, could stop the triumphant progress of mirrors. Different in size and shape, they found their way into grand parlours and humble abodes. Even ironic or moralising paintings failed to discourage people from feasting their eyes upon their reflections.

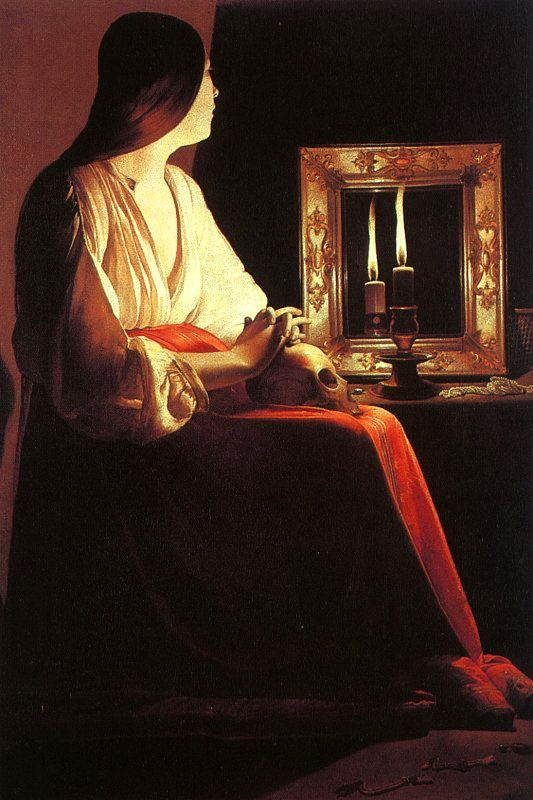

Though in those days, a mirror was an allegory of women’s vanity, a candle it reflected represented the flame of faith shining upon the young woman.

Georges de La Tour. The Penitent Magdalene.1638—1643

‘And here is mirror mine — thou take this gift, o Cypris!’

A woman contemplating herself in a mirror for hours is sure to be of no virtue. So, for a long time, this attribute of women’s love life was branded as ‘an accomplice to licentiousness.' Could it be a mere coincidence that the leading manufacturer of mirrors was Venice, the city notorious for its courtesans!So, in the early Renaissance , none other than Venus was drawn from non-existence to help protect the reputation of her favourite object. Though called Foam-Arisen, she came not on the crest of a wave, but fell from the sky. She entered iconography as a planet represented in the form of a goddess looking in the fatal glass.

At that time, nudity in art was strictly prohibited, and the disobedient ones could easily have found themselves burnt at the stake. Nevertheless, the public’s growing interest in classical culture allowed artists to ‘strip' women. That is how various subjects were introduced that enriched art history with charming images. One of those was Jan Gossaert’s Venus.

Perhaps, it is the mirror that makes an attentive viewer feel some sort of discord comparing the model’s beautiful body and the simplicity of her reflection.

A mirror cannot lie (especially a crooked one)

A common conception of the eighteenth century was that crooked mirrors were objects revealing a person’s true nature. Thus, the mirror, in human culture, started being a symbol of self-discovery.It is possible that this theory was given rise to by anamorphic mirrors — shiftable mirror-like canvases invented in the first half of the seventeenth century. In it, optical displacement made a chaotic picture assemble into an easily perceived image. The effect was even interpreted in a deeply philosophical way, as the truth revealed through mirrors.

A picture in the picture

The 16th century was the period of discoveries, inventions, and the extraordinary progress of science. Man became both the creator and the most important object of art. Human figures, as they were part of the world, were now depicted in most various poses, gestures, movements. Artists started using mirrors enthusiastically — to expand a composition, to show things that the viewers wouldn’t have seen otherwise.Velázquez had ten mirrors in his studio, though in his days, they cost quite a fortune. Once asked why he needed so many of them, he said that the mirrors were his assistants, almost his apprentices. Indeed, a reflection is a picture in a way, except that it only exists for a split second.

‘Tout m’appelle et m’enchaîne à la chair lumineuse Que m’oppose des eaux la paix vertigineuse!’

‘Everything calls me and enchains me to the luminous flesh, what is opposite me in the vertiginous peace of the waters!' — these are the words that Paul Valéry's Narcissus addressed his reflection that he had fallen in love with.The myth, which belongs to the most popular ones, throughout the centuries, has been interpreted in numerous ways. In the Renaissance , Narcissus was even proclaimed the inventor of the art of painting!

Especially popular the myth became in Modernist art that was highly interested in how the subconscious effects on the act of creation. For Modernists, water was not a mere reflection of the young man’s beautiful exterior, but rather a symbol of what he had deep in his soul. Peering into his mirrored image, Narcissus was trying to gain insight into his own subliminal consciousness.

The poetry of everydayness

At the end of the 18th century, the cheval glass was invented. That well-proportioned, portable mirror soon became an indispensable article of daily use for every self-respecting lady. And thus, artists got a blank check to poeticise a humdrum life and the commonest interiors.Pierre Bonnard stuck to depicting the same indoor environment. On the one hand, the indoor objects and furnishings he featured in his canvases were part of the ‘looking-glass world,' on the other hand, they were included into the real environment, where the viewer was standing in front of the picture.

‘Behind my shoulder, in the looking-glass, I saw so often something not called for…’

In the pagan Rus (as well as in other lands), the glass of the mirror was a border between the two worlds, the material and the transcendental ones. Even now, it is still considered that destroying this border — breaking the looking-glass — spells disaster. Russian Old Ritualists regarded mirrors as a gift of hell and never had them in their homes. Looking into a mirror meant committing a sin. The belief held till the end of the 17th century. Then, Peter the Great took power, and now everyone was free to admire their mirror image.This is the only folk subject Karl Bryullov ever painted. In this scene, the mirror is an instrument for Christmas divination. The heroine is peering, both fearfully and hopefully, into the dark shadows behind her.

Other worlds

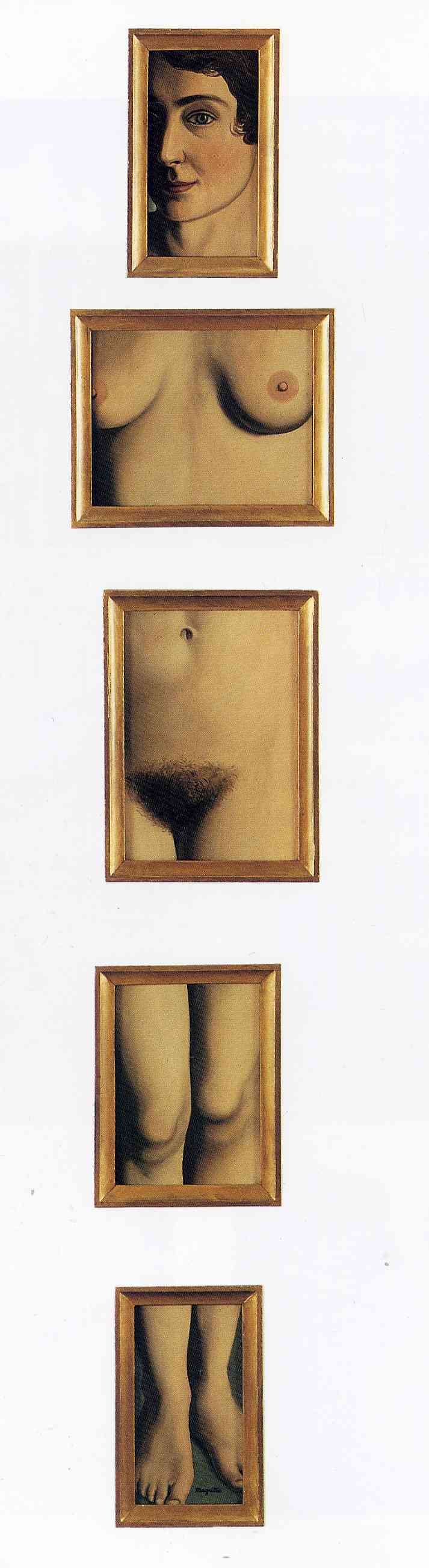

The 20th century was the time when the mirror resumed being regarded as something more than an ordinary everyday object. Again, it was ascribed the mystic power of showing anything it would like to and taking a person into another reality. For example, the Expressionist artists took a liking to the symbolism of vanitas, so they started showing the mirror as a mendacious structure that obscured the real nature of things.As the mirror symbolises truthfulness, it gave Delvaux reasons to believe: whatever attire a lady wears, her real self comes out, nevertheless.

In Magritte's work, a reflection no longer depends on what it is caused by, and starts conflicting — not with the body, but with the mirror and with the laws of physics.

Text by: Yelena Nastyuk