The exhibition of Russian icons in the City Museum of Ljubljana, Slovenia, is the end result of three years of discussion, exploration and cooperation of the museum’s director Blaž Peršin and curator Blaž Vurnik with the Russian counterparts from the State Tretyakov Gallery, the Yaroslavl Art Museum and the Sergiev Posad State History and Art Museum. The icons included in this exhibition and catalogue span the late 13th to the early 20th centuries: from the point when Russian icon painting had already outgrown its adopted Byzantine traditions, to the time of the Bolshevik revolution, when icons as objects of veneration were relegated to storerooms and museum depositories, many even destroyed during the systematic elimination of everything associated with church and religion.

Icons are a distinctive visual feature of Orthodox Christianity and hence of Russian culture in general. The earliest icons were brought to the Russian lands during the time of Christianisation, at the end of the 10th century. In their wake came Byzantine icon painters, who passed their skills on to local students in various Russian principalities. As the demand for icons in the vast Russian territories grew over the centuries, icon-making prospered to the point where at the turn of the 20th century, Russia was known as the land of icons.

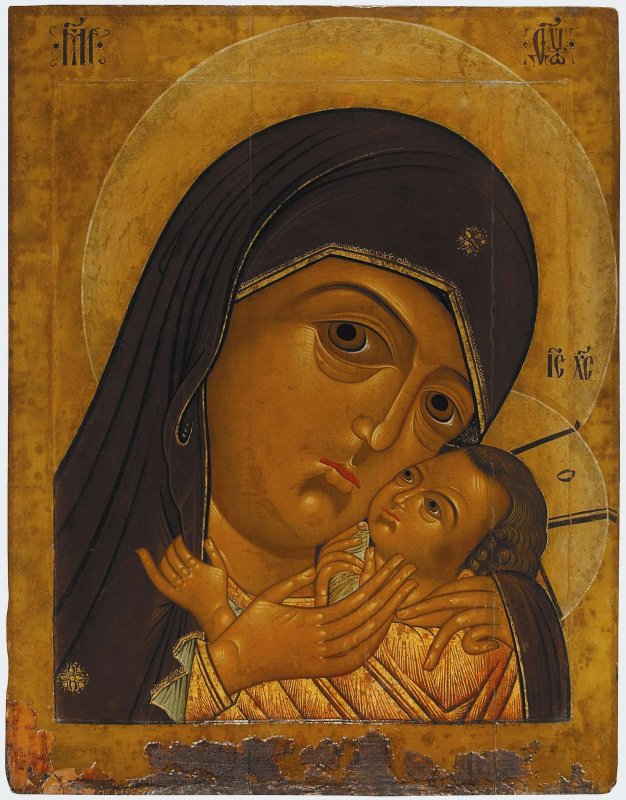

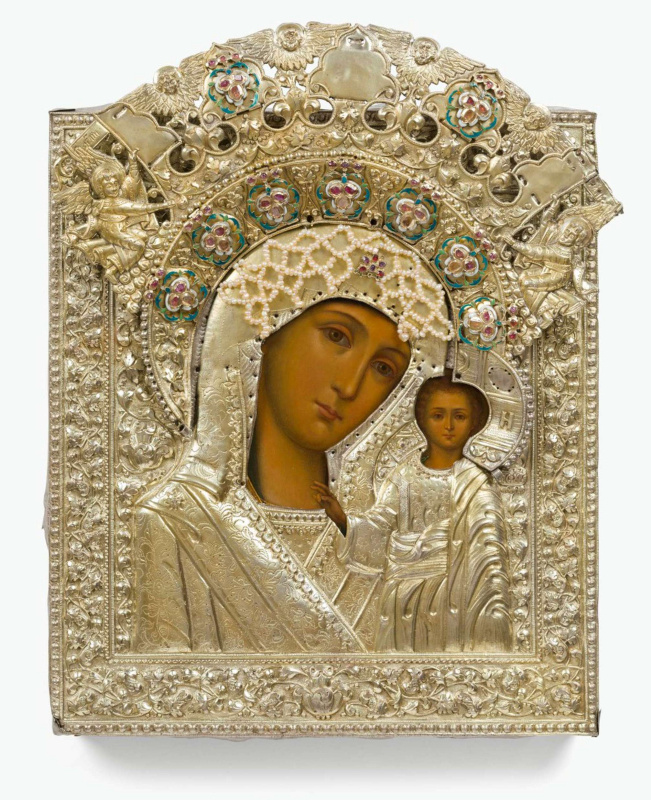

The dominant motif of the works on display here is the Mother of God, whose icons are the most widely venerated and hence the most widely painted in Russia. It is a particularity of icons that they are generally reworkings of ancient originals. These are copied from century to century, their power passed from image to image. Hence the many images of the Mother of God whose titles recall their originals: the Bogolubskaya, the Virgin of Korsun, the Shuisky Virgin, Our Lady of Tikhvin, the Virgin of Vladimir and others. At the start of the 20th century there were over 400 different types of the Mother of God.

The dominant motif of the works on display here is the Mother of God, whose icons are the most widely venerated and hence the most widely painted in Russia. It is a particularity of icons that they are generally reworkings of ancient originals. These are copied from century to century, their power passed from image to image. Hence the many images of the Mother of God whose titles recall their originals: the Bogolubskaya, the Virgin of Korsun, the Shuisky Virgin, Our Lady of Tikhvin, the Virgin of Vladimir and others. At the start of the 20th century there were over 400 different types of the Mother of God.

The idea of recreating an original image is of great significance. Ever since the Second Council of Nicaea toward the end of the 8th century, which marked the end of iconoclasm, tradition has held that adoration is not accorded to the icon but to its prototype: Jesus, the Mother of God, or a saint. The icon allows the faithful to enter into contact with its prototype by establishing two-way communication between the holy figure, who addresses the faithful through the icon, and the faithful, whose duty it is to return the gaze and offer adoration to the depicted figure. Only in this way can the icon become a window to the other world, a way for the faithful to be granted divine benevolence or saintly intercession.

In the more distant past, icons were also used for storytelling and teaching purposes. This was how the common people learned about the lives of Jesus, the Virgin Mary or the saints; this was what perpetuated the memory of rulers and other important figures depicted on the icons they had commissioned or hung in churches whose building they had financed. Icons transmitted biblical teachings and taught the faithful to respect the church and the state. Finally, they represented Russia’s spirit and religious tradition, as attested by attempts to prevent the intrusion of Western styles into Russian icon painting. One of the central actors in these processes in the mid-16th century was Tsar Ivan the Terrible.

In the more distant past, icons were also used for storytelling and teaching purposes. This was how the common people learned about the lives of Jesus, the Virgin Mary or the saints; this was what perpetuated the memory of rulers and other important figures depicted on the icons they had commissioned or hung in churches whose building they had financed. Icons transmitted biblical teachings and taught the faithful to respect the church and the state. Finally, they represented Russia’s spirit and religious tradition, as attested by attempts to prevent the intrusion of Western styles into Russian icon painting. One of the central actors in these processes in the mid-16th century was Tsar Ivan the Terrible.

Also read

Icon painting

The exhibition of Russian icons at the City Museum of Ljubljana is the first in Slovenia to focus on this outstanding cultural patrimony. The last exhibition in Slovenia dedicated to Orthodox icons was held at the National Gallery in 1964; it presented some eighty "Yugoslav" icons, as they were called. Since then, those interested in the cultural patrimony of Orthodox Europe have been limited to a small number of exhibitions in neighbouring countries if they wished to see icons in a museum or gallery setting. This makes the hosting of this precious patrimony at the City Museum of Ljubljana all the more important.

Фото: Городской музей Любляны

The City Museum of Ljubljana has been entrusted with some of the finest works from the collections of three major museums, all of them important guardians of cultural heritage: the State Tretyakov Gallery, the Yaroslavl Art Museum and the Sergiev Posad State History and Art Museum. At all three institutions, icons were carefully selected to fit the theme and chronological framework of the exhibition.

"When planning the exhibition, we decided to complement the icons themselves with a contemporary perspective on the significance of Russian icons in the history of world art, bringing Russian icon painting closer to visitors by addressing its value as it is understood today in the field of contemporary art," the exhibition catalog says. This task was undertaken by exhibition designers Miran Mohar and Luka Savić, who brilliantly arranged the exhibition space to create a discourse on the significance of icons for, and their influence on, 20th century art.

Icons are brought into dialogue with details from works by Robert Mangold, Yves Klein, Mark Rothko, Kazimir Malevich and Josef Albers.

"When planning the exhibition, we decided to complement the icons themselves with a contemporary perspective on the significance of Russian icons in the history of world art, bringing Russian icon painting closer to visitors by addressing its value as it is understood today in the field of contemporary art," the exhibition catalog says. This task was undertaken by exhibition designers Miran Mohar and Luka Savić, who brilliantly arranged the exhibition space to create a discourse on the significance of icons for, and their influence on, 20th century art.

Icons are brought into dialogue with details from works by Robert Mangold, Yves Klein, Mark Rothko, Kazimir Malevich and Josef Albers.

This is why it was decided to have the exhibition of Russian icons coincide with the opening of an exhibition by the IRWIN arts collective entitled Was ist Kunst Hugo Ball. This project by the IRWIN group, whose conceptual premises are often connected with Russian icons, is an homage to this important artistic tradition, which has inspired both modernist and contemporary artistic practices. This exhibition opens up fresh possibilities for new beginnings and interesting collaborations.

"The exhibition of Russian icons is a significant cultural event, adding to the collaboration between two Slavic nations, as well as appealing to the spirit of ecumenism," the curators claim.

Photo: the City Museum of Ljubljana

RUSSIAN ICONS Treasures from Russian Museums exhibition will be on view in the City Museum of Ljubljana until September 15, 2019.

Based on materials of the City Museum of Ljubljana