Perhaps the commonest phrase found in Claude Monet’s letters to his friends is the request to enclose a hundred francs with the reply letter. For decades, he was living on the edge of starvation. If he happened to get some money, he was quick and lavish in spending it on wine, expensive food, the trendiest dresses and bonnets for his wife, and on renting a studio close to the Gare Saint-Lazare. As soon as a week later, he would ask again for so much as a hundred francs — ‘If I don’t get some help, we’ll die of hunger.' Yet Monet believed charity to be a matter of individual concern, so he hardly found it necessary to pay the money back to his benefactors.

Claude Monet reading

1872, 65×50 cm

His good fortune did care for him and blessed him with true friends and devotees. Well, they groaned about it, got angry or annoyed, tried to stonewall on the matter, but, again and again, they gave up in the end and enclosed another hundred francs in a letter. Perhaps, they could not resist Monet’s natural charisma. Or believed honestly in his painting, and understood that, for the sake of French art, nay of the entire Universe, Monet should stay fit — at least well-fed.

Self-portrait with palette

1866, 108.9×71.1 cm

Frédéric Bazille

When Bazille was leaving for Paris, he quite sincerely promised his father to be diligent in studying medicine. But however great pains he took, this science was too hard for him to master. His medical exams were an absolute disaster. So Frédéric started taking classes in Gleyre's studio — rather for fun, indeed, for he had no idea that there, he would meet his closest friends, discover his own artistic gift, and find his true vocation.Renoir, Monet and Bazille, Gleyre’s defiant students, the three peas in a pod, were the first who had an idea of giving a good shake to the dust-covered academic principles. Together they spent time hanging about bars and arguing over art, or rambling in the woods in search of themes and subjects that would be fresh and suffused with light.

They understood one another perfectly, shared the same thoughts, but Bazille’s father regularly sent him a sum of money that was enough to live on, and Monet and Renoir were as poor as church mice. So, Frédéric offered them his studio to work in — for free, just out of friendship. Later, out of friendship, Monet stayed to live there. Sharing meals with the friend seemed quite a natural thing, too.

Women in the garden

1866, 255×205 cm

Monet did not succeed in selling a single picture. A few years were yet to pass before people started paying a ridiculous fifty francs for his landscapes. What a surprise for him it was when Bazille bought his Women in the Garden and valued it himself at 2,500 francs. By comparison, at that time, Monet had to pay 800 francs a year for the studio he was renting. And to be given such money!

‘But I will only be able to pay it by instalments of fifty francs a month,' Bazille warned. Later, he must have wished, many a time, he had not got involved in that venture. Monet kept writing him letters — pleading letters, angry letters, accusing and reproachful ones, — and pressed him for the monthly payments. ‘On 25 July Camille’s baby is due. I’m going to Paris where I’ll be for ten or fifteen days and I’ll need money for a lot of things. Do try and send me a little more then, if only 100 or 150 francs. Please bear it in mind, without it I’ll be in a very awkward position,' ‘It is unbearable to see her suffering so much … I am myself embittered and my wife always sick,' ‘I have to think that what I tell you about my circumstances scarcely concerns you, because I tell you we’re starving,' ‘If I don’t get some help, we’ll die of hunger.'

‘But I will only be able to pay it by instalments of fifty francs a month,' Bazille warned. Later, he must have wished, many a time, he had not got involved in that venture. Monet kept writing him letters — pleading letters, angry letters, accusing and reproachful ones, — and pressed him for the monthly payments. ‘On 25 July Camille’s baby is due. I’m going to Paris where I’ll be for ten or fifteen days and I’ll need money for a lot of things. Do try and send me a little more then, if only 100 or 150 francs. Please bear it in mind, without it I’ll be in a very awkward position,' ‘It is unbearable to see her suffering so much … I am myself embittered and my wife always sick,' ‘I have to think that what I tell you about my circumstances scarcely concerns you, because I tell you we’re starving,' ‘If I don’t get some help, we’ll die of hunger.'

A makeshift hospital. Monet after his accident at Chailly

1865, 47×62 cm

Monet could jump into a railway coach and travel light to a place like Chailly, — to discover there that he had forgotten to take along pencils, paints, and canvases. Then, he would put pen to paper and produce a quick letter to Bazille — do bring me the painting stuff, or how else should I work! Yet again and again did Frédéric give in, though he could well guess what was behind such forgetfulness. Monet had no money for paints, of course!

Monet was a virtuoso of quarrels, and his stubbornness was often insufferable. Once, Bazille had to take great pains while persuading his friend to stay for some days in bed in a provincial hotel after Claude had badly injured his leg. To keep him from getting out of bed, Bazille had an idea of painting Monet with his leg in traction (that was how Bazille’s medical studies came in useful, as he himself made a sort of improvised field hospital in the hotel room).

Bazille was only twenty-nine when he was killed in the war. Then, Monet’s caring fate had to make some twists and turns, involving the war and England, before it was able to pass the ever-starving painter on to another guardian angel.

Monet was a virtuoso of quarrels, and his stubbornness was often insufferable. Once, Bazille had to take great pains while persuading his friend to stay for some days in bed in a provincial hotel after Claude had badly injured his leg. To keep him from getting out of bed, Bazille had an idea of painting Monet with his leg in traction (that was how Bazille’s medical studies came in useful, as he himself made a sort of improvised field hospital in the hotel room).

Bazille was only twenty-nine when he was killed in the war. Then, Monet’s caring fate had to make some twists and turns, involving the war and England, before it was able to pass the ever-starving painter on to another guardian angel.

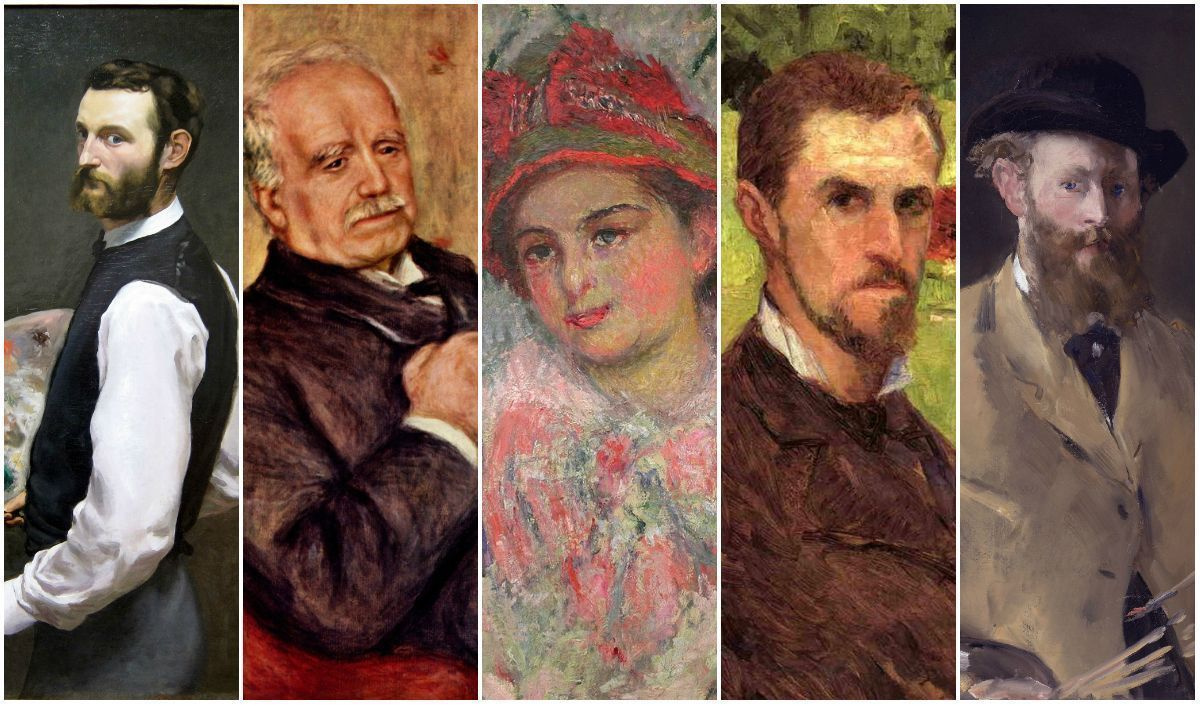

The artist's studio, rue de La Condamine

1870, 98×128 cm

In the picture Studio in Rue de La Condamine (or Bazille’s Studio), Claude Monet, in front of the easel with a canvas on it, is discussing the painting with Édouard Manet and Frédéric Bazille, the creator of the picture. On the stairs, Émile Zola is talking to Renoir sitting below.

The Portrait Of Paul Durand-Ruel

1910, 65×55 cm

Paul Durand-Ruel

Durand-Ruel did not bring Claude any bread (as Renoir sometimes did), and, unlike Bazille, never invited the painter to stay at his place. He was the first to invest money not in the poor and unrecognised artists, but in their art.Bazille was young, careless, and free, and could volunteer to defend his country in the war. Monet and Pissarro, though, could not afford such imprudence, as they had to defend their children. They both fled to England to save their families. Just as young, amazingly tall and singularly high-minded Bazille was killed in battle, these two met Durand-Ruel.

Now, Monet had his own art dealer, who did something more than merely buying his pictures for good money in the hope of selling them some time later. It was a person to turn to for money at any time, on the account of Monet’s paintings yet to be painted. Often, Monet did not scruple to blatantly use him — ‘be so kind to send me some thousands, as I have to pay the people renovating my studio.'

Starting his winter plein air session at Étretat, Monet had no doubt that Durand-Ruel was already waiting for him willing to pay, sight unseen, for all the pictures the artist would bring him. While Monet was obsessed with conveying the glow of sunsets and dawns on haystacks, Americans were lining up in Durand-Ruel's art salon to buy Monet’s new masterpieces.

Durand-Ruel, a respectable and reputable marchand, ran a big risk when he held the Second Impressionist Exhibition in his gallery. Outraged viewers could hardly be kept from spitting in disgust. There were moments when the paintings were under threat of physical attacks — visitors poked their umbrellas in the canvases. People whispered around that Durand-Ruel was mad. He was rapidly losing money, his trustworthiness was declining in his regular customers' eyes, but he kept following his instinct for discovering geniuses. Especially that he was no longer alone — in Paris, there had already appeared some other crazy art collectors who had taken to buying Impressionist paintings.

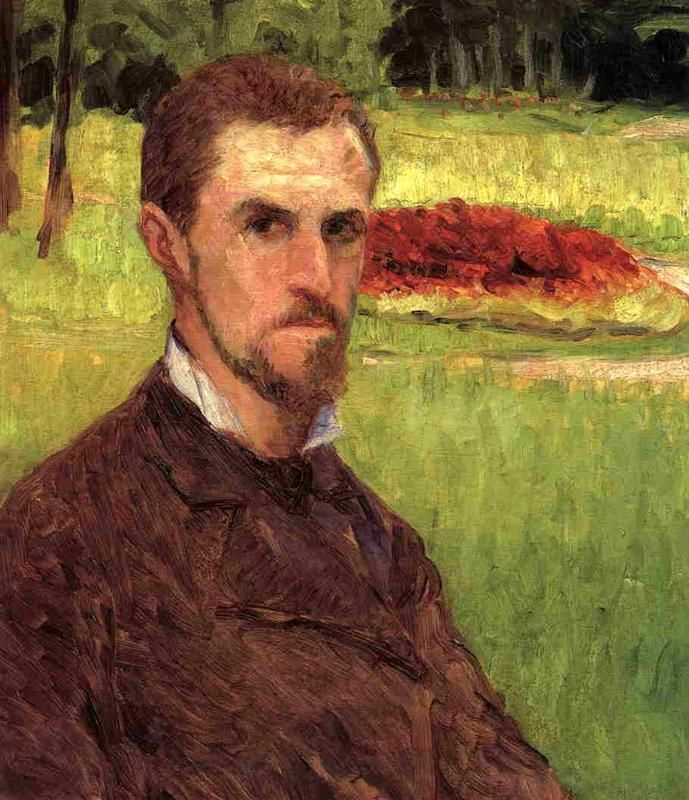

Self-portrait in the Park in hyères

1870-th

, 64×48 cm

Gustave Caillebotte

Caillebotte was rich — incredibly, fabulously rich. An aristocrat, a dandy, a brilliant Sorbonne student, a dedicated stamp-collector and yachtsman, a talented engineer, progressive and highly educated, — suddenly, Caillebotte took to painting. The new, revolutionary painting, of course.As an artist, Caillebotte is traditionally numbered among other Impressionists, mainly due to his long and close friendship with them. Caillebotte’s painting style is so distinctive and independent, and his outlook on the world so individual that they cannot be limited to Impressionism only. One thing is certain, though: if it had not been for Caillebotte, his artistic friends' life and welfare would have been quite miserable.

Caillebotte used to lend money to Claude Monet and Auguste Renoir — and the very next thing he did was adding an item to his will about releasing these two from all their debts. He bought Impressionists pictures when no one did so. Once, Caillebotte put up his collection of unappreciated paintings for an Impressionist auction. There was no one who would like to acquire such trash. Caillebotte refused to believe it, and bought the pictures he owned — anew, at inflated prices. It was an attempt to rouse the audience. It failed.

In 1877, Caillebotte, at his own expense, rented a room for the Third Impressionist Exhibition. He himself paid for the publicity, and himself hung up the pictures, most of which he was the owner of. This exhibition became known as Caillebotte’s Exhibition.

Gustave Caillebotte’s will included sixty-eight Impressionist paintings, among them fourteen works by Claude Monet. The artist stipulated that, after his death, these pictures must not be separated, but be displayed in the Luxembourg Palace, and later, in the Louvre. However, Caillebotte died too early, when the French government was not ready yet to execute this insane will — ‘there would have to be a great slackening of public morality for such filth to be accepted.' Two years later, though, thirty-eight pictures were taken to the Luxembourg Palace. The remaining, rejected ones were added to Albert C. Barnes's collection and travelled to Philadelphia.

Gustave Caillebotte’s will included sixty-eight Impressionist paintings, among them fourteen works by Claude Monet. The artist stipulated that, after his death, these pictures must not be separated, but be displayed in the Luxembourg Palace, and later, in the Louvre. However, Caillebotte died too early, when the French government was not ready yet to execute this insane will — ‘there would have to be a great slackening of public morality for such filth to be accepted.' Two years later, though, thirty-eight pictures were taken to the Luxembourg Palace. The remaining, rejected ones were added to Albert C. Barnes's collection and travelled to Philadelphia.

Blanche Aside

1880, 46×38 cm

Blanche Hoschedé

A friend of Monet’s, Georges Clemenceau called Blanche ‘Blue Angel' — as though to confirm our idea that a whole host of guardians were specially trained and detached to the earth, with the mission of supporting and rescuing the painter throughout his life.Blanche was Monet’s stepdaughter. Later, she became his daughter-in-law, as she married the artist’s son. She was only thirteen when her parents and Monet’s family shared the expenses of renting a house and started living there together. After some years, Blanche’s father left his family, and Monet’s first wife died. Claude’s two sons and Alice’s six children became one family. Together, they persisted through the years of starvation and cold. Very soon, the children fell out of the habit of hanging a Christmas stocking by the fireplace and waiting for miracles. Of all the big family, Blanche was the only one who became a true painter. Being only a teenager, she would get up at daybreak in order to see the sunrise in papa Monet's company, to follow him pushing a trolley with canvases, and to paint by his side. Monet really admired the girl’s talent and helped her with advice. Obviously, she was Claude Monet’s only student.

In the woods at Giverny

1887, 91.4×97.8 cm

Years later, when her mother Alice (by that time, the artist’s wife) and Blanche’s husband Jean, one after the other, had gone forever, Blanche returned to Giverny — to become the only person who did not let Monet die of grief, blindness, and helplessness.

At that time, Monet could no longer discern colours. So, every morning, Blanche laid out the tubes of paints in a certain order (see Monet’s works of the late period — 1, 2). No one else was allowed to approach the artist’s workplace. During World War I, Monet’s gardeners left to fight — and Blanche took over looking after his garden. She cooked for him, cleaned, washed his palettes, spoke to journalists, inspired him, and never allowed him to fall out of touch with the world. A letter by Monet has survived, written with a pencil. He believed, while writing, that it was a well-sharpened pencil — actually, the pencil lead was broken, and only ugly letter-shaped rips were left on the paper. He could hardly see anything, but Blanche was his eyes.

After papa Monet's death, his dearest one of all the young Monet-Hoschedé generation, his Blue Angel Blanche preserved the Giverny house and garden. It is owing to her labours that roses and rhododendrons still grow there, the window shutters are well-painted, and there are water-lilies floating on the lake below the Japanese footbridge. And Clemenceau believed that but for Blanche, Monet would have never painted his celebrated Nymphéas panels.

At that time, Monet could no longer discern colours. So, every morning, Blanche laid out the tubes of paints in a certain order (see Monet’s works of the late period — 1, 2). No one else was allowed to approach the artist’s workplace. During World War I, Monet’s gardeners left to fight — and Blanche took over looking after his garden. She cooked for him, cleaned, washed his palettes, spoke to journalists, inspired him, and never allowed him to fall out of touch with the world. A letter by Monet has survived, written with a pencil. He believed, while writing, that it was a well-sharpened pencil — actually, the pencil lead was broken, and only ugly letter-shaped rips were left on the paper. He could hardly see anything, but Blanche was his eyes.

After papa Monet's death, his dearest one of all the young Monet-Hoschedé generation, his Blue Angel Blanche preserved the Giverny house and garden. It is owing to her labours that roses and rhododendrons still grow there, the window shutters are well-painted, and there are water-lilies floating on the lake below the Japanese footbridge. And Clemenceau believed that but for Blanche, Monet would have never painted his celebrated Nymphéas panels.

Self-portrait with palette

1879, 83×67 cm

Édouard Manet

Claude Monet believed in the work he was destined to do, and this belief was almost beyond human imagination. As for money, it was number ten in the priority list. However, when he, at long last, rose to fame, wealth, and honours, he kept on grumbling and scolding, never abandoned his plein air painting sessions, and never lost a jot of his true self and of his faithfulness to the friends who used to save him. Now, he could afford it.Édouard Manet was one of the affluent dandies who Claude used to address with his send-me-money letters. Though Monet discharged those debts rather late, the interest he paid was extremely high: he saved his friend’s masterpiece from being sold abroad.

Olympia

1863, 130.5×190 cm

The Americans were especially keen to part with their money when they could scent true art where the French were only about to start recognising it. Édouard Manet’s Olympia was supposed to leave for America to join a private collection. An art lover from abroad offered the painter’s widow pretty good money for it. Then Monet put off his Grainstacks and got down to writing dozens of letters to artists, to writers — to everyone who was able to understand what he had in mind: raising twenty thousand francs to purchase Olympia and donate it to the State.

Of course, Monet was not so naïve to believe that the picture would be immediately accepted. Nevertheless, it remained in Paris. It found its way to the Louvre as soon as the situation changed and the French people’s eyes got adjusted to the shine of the new art. He himself contributed a thousand francs. Of his friends, one sent twenty-five, another one fifty, some gave five hundred, some a thousand — and in the end, he collected the sum that was needed! Some seventeen years were yet to pass — and Olympia would hang in the Louvre.

Of course, Monet was not so naïve to believe that the picture would be immediately accepted. Nevertheless, it remained in Paris. It found its way to the Louvre as soon as the situation changed and the French people’s eyes got adjusted to the shine of the new art. He himself contributed a thousand francs. Of his friends, one sent twenty-five, another one fifty, some gave five hundred, some a thousand — and in the end, he collected the sum that was needed! Some seventeen years were yet to pass — and Olympia would hang in the Louvre.

When Monet had sorted out everything about the picture, Manet, the old debts, and the Louvre, he returned to his grainstacks. Almost all the canvases of this series soon travelled overseas: American collectors bought them at a price of two thousand each.

Text by: Anna Sidelnikova

Text by: Anna Sidelnikova