log in

Enter site

Login to use Arthive functionality to the maximum

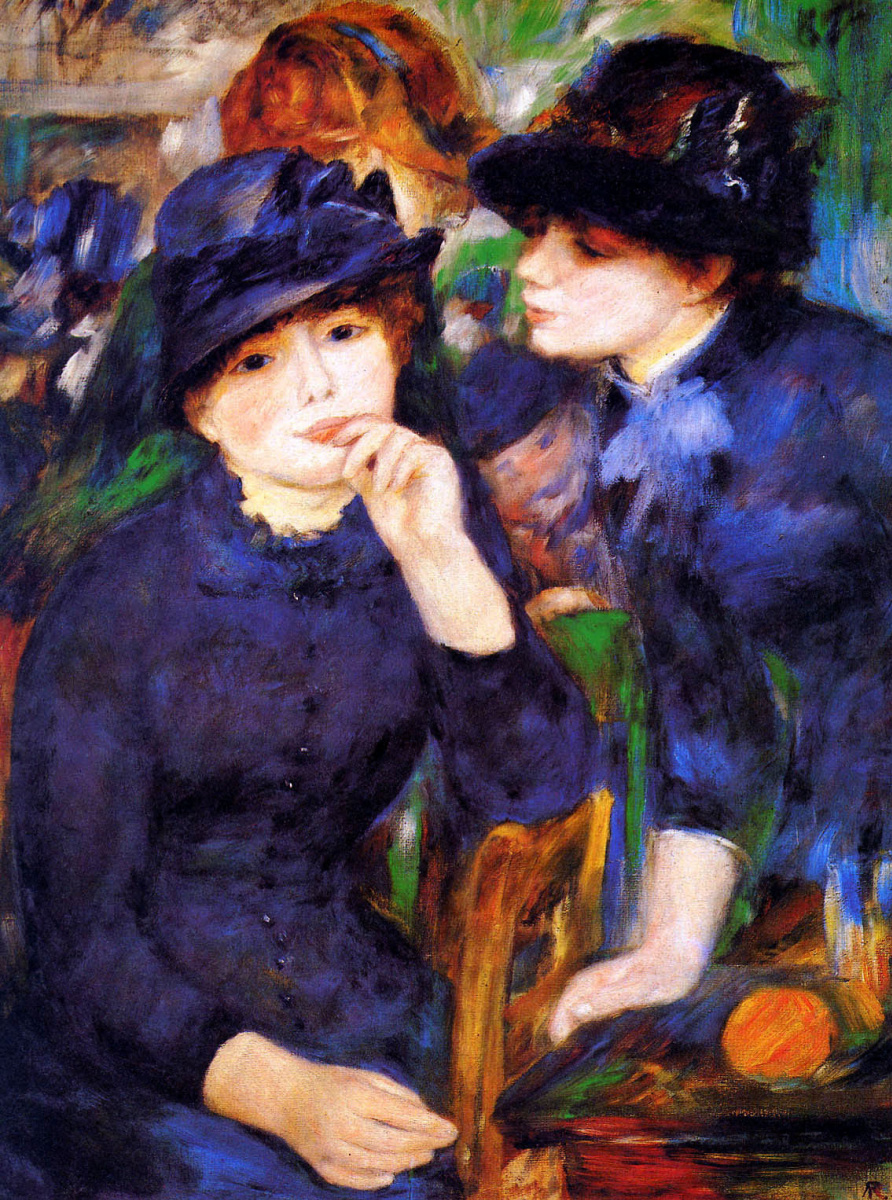

Two Girls in Black

Pierre Auguste Renoir • Peinture, 1882, 81.3×65.2 cm

Descriptif de la toile «Two Girls in Black»

In the early 1880s, Renoir was 40, it was exactly the middle of his life. He met Aline Charigot, who would soon become his wife. In those years, Renoir went to Italy, got tired of the skills of Michelangelo and Bernini, reached Naples and experienced the most powerful artistic shock in his life – the frescoes of Pompeii in the local Neapolitan museum. Later, he called it the painting, which looked eternal, but did not harp on about it, the eternity of everyday life, noticed from around the corner of the next house. Afterwards, Renoir went to Algeria, and back to Paris, intoxicated by the bright white light of the East. And in this middle of his life, enamoured and filled with new artistic impressions, he declared that he had come to the end of Impressionism.

It may seem strange, given that all the Renoir’s oeuvre is called Impressionism. What was it in the remaining 40 years? The Two Girls in Black was created just in this fracture period, at the end of Renoir’s personal Impressionism and at the beginning of the new period.

After he has returned from Italy and Algeria, he did not change his models. The subjects of his paintings are the same women of Montmartre who posed for the Ball in the Moulin de la Galette, seamstresses and laundresses, young girls who never concerned about the ideals of virtue. They worked hard during the day and danced carelessly in the night. They gave birth to children out of wedlock and willingly posed for young artists to earn extra money.

Renoir has changed neither the characters, nor motives, he has modified his painting technique. Keeping in mind the Pompeian frescoes, eternal and magnificent, he refused to use small, separate strokes, sharp sunlight glints on the skin, sketchiness. The foreground figures acquired clear outlines, as if Renoir brought them into focus, striving for greater clarity, smooth color transitions and splitting the deep versatile background into several saturated color spots.

The black color is an intruder here. It should not be there. After all, the Impressionists abandoned the dark colors and deleted them from the palette. Even the shadows, thrown away by objects and trees on a sunny day, they learned to paint them with purple and yellow. And here it shamelessly occupies two thirds of the picture space: dresses, hats. But the Renoir’s black turns out to be not black. These are the shades of blue ultramarine, yellow and madder lake.

The friend of the sitting girl runs up from the vivid red-hot space. Renoir did not like critics and art dealers to call his heroines meditating. “They are not meditating!” he laughed. She is thinking, watching, recalling something beautiful, waiting, dreaming, resting after a dance, but not meditating, by no means. Her friend breaks in from the outside, loud, dancing space, therefore she has motion blurred hat decorations and bow. In a moment, the sitting girl would turn back, and her hat would float in this general evening movement. A second to dance or laugh, to embraces or surprise.

Renoir was wrong. It was not he to say goodbye to Impressionism, it was Impressionism to change and accommodate somewhat more.

Author: Anna Sidelnikova

It may seem strange, given that all the Renoir’s oeuvre is called Impressionism. What was it in the remaining 40 years? The Two Girls in Black was created just in this fracture period, at the end of Renoir’s personal Impressionism and at the beginning of the new period.

After he has returned from Italy and Algeria, he did not change his models. The subjects of his paintings are the same women of Montmartre who posed for the Ball in the Moulin de la Galette, seamstresses and laundresses, young girls who never concerned about the ideals of virtue. They worked hard during the day and danced carelessly in the night. They gave birth to children out of wedlock and willingly posed for young artists to earn extra money.

Renoir has changed neither the characters, nor motives, he has modified his painting technique. Keeping in mind the Pompeian frescoes, eternal and magnificent, he refused to use small, separate strokes, sharp sunlight glints on the skin, sketchiness. The foreground figures acquired clear outlines, as if Renoir brought them into focus, striving for greater clarity, smooth color transitions and splitting the deep versatile background into several saturated color spots.

The black color is an intruder here. It should not be there. After all, the Impressionists abandoned the dark colors and deleted them from the palette. Even the shadows, thrown away by objects and trees on a sunny day, they learned to paint them with purple and yellow. And here it shamelessly occupies two thirds of the picture space: dresses, hats. But the Renoir’s black turns out to be not black. These are the shades of blue ultramarine, yellow and madder lake.

The friend of the sitting girl runs up from the vivid red-hot space. Renoir did not like critics and art dealers to call his heroines meditating. “They are not meditating!” he laughed. She is thinking, watching, recalling something beautiful, waiting, dreaming, resting after a dance, but not meditating, by no means. Her friend breaks in from the outside, loud, dancing space, therefore she has motion blurred hat decorations and bow. In a moment, the sitting girl would turn back, and her hat would float in this general evening movement. A second to dance or laugh, to embraces or surprise.

Renoir was wrong. It was not he to say goodbye to Impressionism, it was Impressionism to change and accommodate somewhat more.

Author: Anna Sidelnikova