Сергей Павлович Дягилев (31 марта 1872, Селищи, Новгородская губерния - 19 августа 1929, Венеция) - русский театральный и художественный деятель, один из основателей группы «Мир Искусства». Своей просветительской деятельностью внес существенный вклад в развитие русского изобразительного искусства. Организатор «Русских сезонов» в Париже и труппы «Русский балет Дягилева», антрепренер.

When Sergei Diaghilev was five, he got the title role in a home production of the Hop-o'-My-Thumb fairy tale. While rehearsing, he was not afraid of the ogre (played by his uncle Nikolai) at all, and even sat on his lap. In the pre-premiere turmoil, the boy did not notice that his uncle had carefully made up.

The uncle was tall and obese, his fake beard and moustache made him unrecognisable. Tangled jet black hair, eyes burning with hell-fire, it was no longer Uncle Nikolai, but a huge hungry monster. Little Sergei ran from the stage in tears. And although he got a standing ovation (the adults thought that the boy was only playing fright), he could not come to his senses for a long time — he first felt the terrible power of art.

You cannot say for sure how important was the role of this episode in the further fate of Sergei Diaghilev. But since then, Diaghilev, a man whose name is strongly associated with the theatre, has never appeared on stage himself.

Under the dingy provincial sky

Sergei Diaghilev’s mother died shortly after his birth. Two years later, his father, Pavel Diaghilev, remarried. At that time, he served in St. Petersburg with the rank of colonel as a cavalry officer. Pavel Pavlovich was a musically gifted person. The possessor of an excellent tenor, he was a welcome guest in the capital’s salons and at high society parties, he even conducted the orchestra at balls in the palace of Grand Duke Nikolai Nikolaevich the Elder. In addition to the musical talent, Pavel Diaghilev had another one, to make debts. It would seem that many people know how to borrow, so what is the precedent? But Pavel Pavlovich was not a red tape, he virtually did not drink or play cards, according to the testimony of relatives, he did not tolerate gambling at all. Nevertheless, by 1882, he had accumulated about 200 thousand of debt — creditors were tightening the ring.

Seeing no other way out, Pavel Diaghilev agreed to his father’s offer — to pay off the debts if he returned to the family nest with his wife and children.

In 1965, a Parisian square would be named in honour of Sergei Diaghilev. In the meantime, he found himself in Perm, being ten years old.

Provincial life was not so bad for the Diaghilevs. Thanks to his network, Pavel Pavlovich received the post of a district military commander. The transfer from cavalry to infantry did not cause him much enthusiasm, but in a sense he managed to stay in the saddle. His military career continued (in the end, Pavel Diaghilev rose to the rank of general). As for the cultural life, it lacked the capital’s splendour, but was still in full swing. Sergei’s grandfather, Pavel Dmitrievich, was a wealthy man; it would not be an exaggeration to say that the elder Diaghilev was a city-forming figure in Perm. Having made his forutne on the supply of alcohol to the treasury (among other things, Pavel Diaghilev ran his own vodka distillery), he rebuilt the local opera house, actively donated to monasteries and almshouses, was a member of all kinds of boards of trustees, in a word, was a prominent public figure. The owner of a solid collection of paintings and a rich library, it was he who instilled an interest in painting in Sergei.

In addition, he was a connoisseur of music, and also a brilliant pianist. Now, when his sweet-voiced son has moved to Perm, music in the Diaghilevs’ house sounded constantly. Often they were joined by Pavel Dmitrievich’s eldest son, Ivan, also a brilliant pianist and cellist, a student of Anton Rubinstein. Sometimes a real orchestra would gather in the house — musicians from the local opera would come to see the Diaghilevs. They played Dargomyzhsky, Glinka, Tchaikovsky. The latter was Diaghilev’s relative; in the house, they called him “Uncle Petya”.

Concerts, home performances, literary evenings — the local intelligentsia called the Diaghilevs’ house “Perm Athens”. And this definition was used without a shadow of irony.

Genes and incessant cultural accompaniment did their job — creativity awakened early in Sergei Diaghilev. He played music, composed, sang. The environment in which he grew up left him no choice. Going to St. Petersburg to study law, he knew that he would become neither a lawyer nor a judge.

The Perm idyll of the Diaghilevs ended with Sergei’s childhood. In 1890, the court declared his father an insolvent debtor. Almost all his property, including the house, was auctioned off.

The chronicles are silent about how Pavel Pavlovich lost not only his own fortune, but also that of his father. Maybe, he sang it off.

The uncle was tall and obese, his fake beard and moustache made him unrecognisable. Tangled jet black hair, eyes burning with hell-fire, it was no longer Uncle Nikolai, but a huge hungry monster. Little Sergei ran from the stage in tears. And although he got a standing ovation (the adults thought that the boy was only playing fright), he could not come to his senses for a long time — he first felt the terrible power of art.

You cannot say for sure how important was the role of this episode in the further fate of Sergei Diaghilev. But since then, Diaghilev, a man whose name is strongly associated with the theatre, has never appeared on stage himself.

Under the dingy provincial sky

Sergei Diaghilev’s mother died shortly after his birth. Two years later, his father, Pavel Diaghilev, remarried. At that time, he served in St. Petersburg with the rank of colonel as a cavalry officer. Pavel Pavlovich was a musically gifted person. The possessor of an excellent tenor, he was a welcome guest in the capital’s salons and at high society parties, he even conducted the orchestra at balls in the palace of Grand Duke Nikolai Nikolaevich the Elder. In addition to the musical talent, Pavel Diaghilev had another one, to make debts. It would seem that many people know how to borrow, so what is the precedent? But Pavel Pavlovich was not a red tape, he virtually did not drink or play cards, according to the testimony of relatives, he did not tolerate gambling at all. Nevertheless, by 1882, he had accumulated about 200 thousand of debt — creditors were tightening the ring.

Seeing no other way out, Pavel Diaghilev agreed to his father’s offer — to pay off the debts if he returned to the family nest with his wife and children.

In 1965, a Parisian square would be named in honour of Sergei Diaghilev. In the meantime, he found himself in Perm, being ten years old.

Provincial life was not so bad for the Diaghilevs. Thanks to his network, Pavel Pavlovich received the post of a district military commander. The transfer from cavalry to infantry did not cause him much enthusiasm, but in a sense he managed to stay in the saddle. His military career continued (in the end, Pavel Diaghilev rose to the rank of general). As for the cultural life, it lacked the capital’s splendour, but was still in full swing. Sergei’s grandfather, Pavel Dmitrievich, was a wealthy man; it would not be an exaggeration to say that the elder Diaghilev was a city-forming figure in Perm. Having made his forutne on the supply of alcohol to the treasury (among other things, Pavel Diaghilev ran his own vodka distillery), he rebuilt the local opera house, actively donated to monasteries and almshouses, was a member of all kinds of boards of trustees, in a word, was a prominent public figure. The owner of a solid collection of paintings and a rich library, it was he who instilled an interest in painting in Sergei.

In addition, he was a connoisseur of music, and also a brilliant pianist. Now, when his sweet-voiced son has moved to Perm, music in the Diaghilevs’ house sounded constantly. Often they were joined by Pavel Dmitrievich’s eldest son, Ivan, also a brilliant pianist and cellist, a student of Anton Rubinstein. Sometimes a real orchestra would gather in the house — musicians from the local opera would come to see the Diaghilevs. They played Dargomyzhsky, Glinka, Tchaikovsky. The latter was Diaghilev’s relative; in the house, they called him “Uncle Petya”.

Concerts, home performances, literary evenings — the local intelligentsia called the Diaghilevs’ house “Perm Athens”. And this definition was used without a shadow of irony.

Genes and incessant cultural accompaniment did their job — creativity awakened early in Sergei Diaghilev. He played music, composed, sang. The environment in which he grew up left him no choice. Going to St. Petersburg to study law, he knew that he would become neither a lawyer nor a judge.

The Perm idyll of the Diaghilevs ended with Sergei’s childhood. In 1890, the court declared his father an insolvent debtor. Almost all his property, including the house, was auctioned off.

The chronicles are silent about how Pavel Pavlovich lost not only his own fortune, but also that of his father. Maybe, he sang it off.

Portrait of Sergei Pavlovich Diaghilev with his nanny

1906, 161×116 cm

Young lions

In the Perm gymnasium, Sergei Diaghilev was one of the best students. He was not notable for diligence, rather the opposite. But the cultural baggage received at home raised him above the average classmate to an unattainable height. Fluent in French and German, musically gifted, versed in literature and painting, he was developed beyond his years, had a reputation for being an intellectual and witty against the background of others. Diaghilev was everyone’s favourite — not only of his peers, but also mentors listened to him with admiration. He himself treated others with the condescending benevolence that came so easily to those who felt superior.

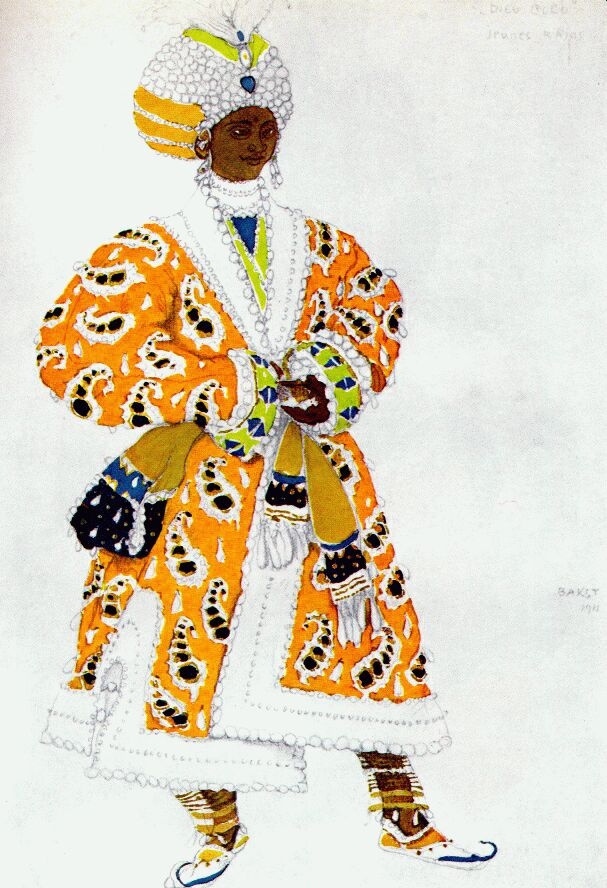

The situation changed after Diaghilev had met his cousin Dmitry Filosofov and his friends Alexander Benois, Valentin Nouvel, Léon Bakst (still Leib Rosenberg at that time). It was the capital’s gilded youth. They were smart. They were obsessed with art. They were really talented. In simple terms, they showed off terribly. This time Diaghilev seemed simple, superficial and hopelessly provincial against their background.

Recalling his acquaintance with Diaghilev, Alexander Benois wrote: “He seemed a fine guy to us, a big provincial man, perhaps not very smart, a little heavy-footed, a little primitive, but generally nice.” He was accepted into the company, but only as a supplement to his brilliant cousin.

Diaghilev used his studies at the university as a screen. He did not associate his future with legal practice, he was going to become a singer and took vocal lessons from the Italian Antonio Cotogni. Beside that, Diaghilev studied composing under Rimsky-Korsakov. His voice, according to eyewitnesses, had a strong, but too shrill, unpleasant timbre. His cousin Zinaida Kmenetskaya wrote in her memoirs that Sergei, “according to a strange fantasy, sang a lot of female arias”, making his unhappy audience bewildered.

As for his musical compositions, even his friends found them too pretentious, chaotic and redundant in terms of his Italian manner. This did not stop Diaghilev, he was arrogant, painfully ambitious, and stubborn. Once he had a serious quarrel with his mentor. Rimsky-Korsakov, when having lost all his patience, he bluntly declared that Diaghilev would not be a composer. Sergei turned pale and blurted out: “You will see which of us will be more famous!”

The spirit of friendly but no less fierce rivalry, which reigned in the Diaghilev’s new environment, forced him to develop. However, the provincial duckling did not immediately turn into a beautiful swan.

At first, Diaghilev, with his exorbitantly large head and the same ambitions, pretty much annoyed his urbanely friends from the capital. For example, making his way to his place in the theatre, he barely nodded to his acquaintances from the “ordinary people”, but obsequiously bowed to those who, in his opinion, had weight in society. When abroad, he emphasized his noble origins, introducing himself exclusively as “Serge de Diaghileff”. Upon his return, he tried to “amaze” friends with stories about his personal meetings with the great ones: Émile Zola, Adolph von Menzel or Jules Massenet. His new friends saw signs of snobbery, if not foppery in him.

In addition, the young Diaghilev was noisy and greedy for special effects. He laughed deafeningly, grew a mustache to resemble Peter I, wore a monocle that was useless in an ophthalmological sense. It’s enough to say that in the opinion of some of his associates, he chose the Faculty of Law for the sake of the dandy uniform with a sword attached.

And yet, behind all this annoying provincialism, there was something captivating in him — spontaneity, optimism, and irrepressible energy.

In the Perm gymnasium, Sergei Diaghilev was one of the best students. He was not notable for diligence, rather the opposite. But the cultural baggage received at home raised him above the average classmate to an unattainable height. Fluent in French and German, musically gifted, versed in literature and painting, he was developed beyond his years, had a reputation for being an intellectual and witty against the background of others. Diaghilev was everyone’s favourite — not only of his peers, but also mentors listened to him with admiration. He himself treated others with the condescending benevolence that came so easily to those who felt superior.

The situation changed after Diaghilev had met his cousin Dmitry Filosofov and his friends Alexander Benois, Valentin Nouvel, Léon Bakst (still Leib Rosenberg at that time). It was the capital’s gilded youth. They were smart. They were obsessed with art. They were really talented. In simple terms, they showed off terribly. This time Diaghilev seemed simple, superficial and hopelessly provincial against their background.

Recalling his acquaintance with Diaghilev, Alexander Benois wrote: “He seemed a fine guy to us, a big provincial man, perhaps not very smart, a little heavy-footed, a little primitive, but generally nice.” He was accepted into the company, but only as a supplement to his brilliant cousin.

Diaghilev used his studies at the university as a screen. He did not associate his future with legal practice, he was going to become a singer and took vocal lessons from the Italian Antonio Cotogni. Beside that, Diaghilev studied composing under Rimsky-Korsakov. His voice, according to eyewitnesses, had a strong, but too shrill, unpleasant timbre. His cousin Zinaida Kmenetskaya wrote in her memoirs that Sergei, “according to a strange fantasy, sang a lot of female arias”, making his unhappy audience bewildered.

As for his musical compositions, even his friends found them too pretentious, chaotic and redundant in terms of his Italian manner. This did not stop Diaghilev, he was arrogant, painfully ambitious, and stubborn. Once he had a serious quarrel with his mentor. Rimsky-Korsakov, when having lost all his patience, he bluntly declared that Diaghilev would not be a composer. Sergei turned pale and blurted out: “You will see which of us will be more famous!”

The spirit of friendly but no less fierce rivalry, which reigned in the Diaghilev’s new environment, forced him to develop. However, the provincial duckling did not immediately turn into a beautiful swan.

At first, Diaghilev, with his exorbitantly large head and the same ambitions, pretty much annoyed his urbanely friends from the capital. For example, making his way to his place in the theatre, he barely nodded to his acquaintances from the “ordinary people”, but obsequiously bowed to those who, in his opinion, had weight in society. When abroad, he emphasized his noble origins, introducing himself exclusively as “Serge de Diaghileff”. Upon his return, he tried to “amaze” friends with stories about his personal meetings with the great ones: Émile Zola, Adolph von Menzel or Jules Massenet. His new friends saw signs of snobbery, if not foppery in him.

In addition, the young Diaghilev was noisy and greedy for special effects. He laughed deafeningly, grew a mustache to resemble Peter I, wore a monocle that was useless in an ophthalmological sense. It’s enough to say that in the opinion of some of his associates, he chose the Faculty of Law for the sake of the dandy uniform with a sword attached.

And yet, behind all this annoying provincialism, there was something captivating in him — spontaneity, optimism, and irrepressible energy.

SP Dyagilev e V.F. Nouvelle in 15 anni. caricatura

1901, 24.5×21.1 cm

In his memoirs, Alexander Benois described one of his first meetings with Diaghilev. Wanting to “probe” his new acquaintance for his tastes and mental abilities, Benois started another art criticism discussion. It was out of town. It was a hot afternoon, the young men stretched out on the grass. Lying on his back with his eyes closed, Benois selflessly played smart and missed an attack. “On my back, I could not follow what Sergei was doing, and therefore I was taken by surprise when he pounced on me and began to pummel me, challenging me to fight and hooting with laughter. We never did anything like this among us; we were all “well-bred mama’s sons”. Moreover, I immediately realized that the fat sturdy Sergei was stronger than me and that I was not good. The elder risked being humiliated. All that remained was to finagle and I yelled shrilly: “You broke my arm!” I will remember this incident forever. He even acquired the character of the famous symbol. In my relationship with Sergei, I often recalled it, both in those cases when he pounced on me again (already in a figurative sense), and when I managed to get revenge and I turned out to be the winner. The mutual relations of a certain struggle continued between us for many subsequent years, but I’d rather say that this competition gave a special vitality and acuteness to our friendship and affected our activities in a beneficial way.”

Igor Stravinsky, Sergei Diaghilev, Léon Bakst and an unknown lady. Switzerland, 1915 (photo source forbes.ru)

In the Mir Iskusstva — World of Art

A certain “turning point” occurred after his trip to Europe in 1895. Much to the relief of those around him, by that time Diaghilev had practically abandoned singing and was disillusioned with composing. Painting attracted him more and more. It started with collecting — from the trip, Sergei brought several portraits by Franz von Lenbach, watercolours by Hans von Bartels, a large painting by Ludwig Dill, Menzel’s drawings — such a collection made him at least a serious amateur in the eyes of his fellow artists. A year later, Diaghilev published an article titled “Aquarelle Exhibition” in the Novosti i Birzhevaya Gazeta newspaper, making his first public appearance as an art critic. And a year later, he organized an exhibition of English and German watercolours in the museum of the Stieglitz School — Diaghilev’s debut as an impresario.

In this role, Diaghilev unexpectedly brightened up: his remarkable organizational skills (which even close people did not suspect of him), his ebullient energy and insatiable pride, finally headed in the right direction. In modern terms, Diaghilev, who seemed a superficial dilettante, suddenly became a perfectionist in the field of producing. Working on articles or art books, he immersed himself so deeply in the topic that he became a real expert. While preparing exhibitions, he delved into every detail. Diaghilev personally supervised all the accompanying processes — the cost of loaders, advertising in newspapers, decoration of halls, selection of paintings. He travelled around Europe, met progressive artists, persuaded, charmed, infected with his enthusiasm. Or, on the contrary, he made enemies by choosing paintings that seemed secondary to the artists, and rejecting those that they liked more. In his work, Diaghilev was a dictator and relied solely on his tastes and flair.

Anna Ostroumova-Lebedeva recalled: “There used to be a great rush at the exhibition; Diaghilev, like a whirlwind, rushed over it, keeping up everywhere. He does not go to bed at night, but he takes off his jacket and carries pictures along with the workers, unpacks the boxes, hangs and re-hang items — dusty but cheerful, he infected everyone around him with enthusiasm. The workers, the artel men obeyed him implicitly, and when he addressed them with a joking word, they smiled broadly at him, sometimes laughing loudly. And everyone kept up on time.”

Coming home in the early morning, Diaghilev would take a bath, change into clean clothes and return to the exhibition first to meet the guests. Among whom, by the way, there were also Nicholas, empresses, and the Grand Dukes — the habit of bowing to the right people in the theatre came in handy to Sergei Pavlovich.

The third exhibition of paintings by the Mir Iskusstva magazine at the Academy of Arts, 1901. Photo: State Russian Museum, source: russiainphoto.ru

Diaghilev quickly realized that his ambitions extended beyond organizing art exhibitions. Together with Alexander Benois, he founded the Mir Iskusstva art association, and the magazine of the same name after it. The core of the association, in addition to Diaghilev and Benois, consisted of the same Dmitry Filosofov, Léon Bakst and Walter Nouvel. However, now no one doubted that the main driving force and the undoubted leader was Diaghilev.

Mir Iskusstva was conceived as an alternative — to the Academy, the Itinerants, everyone. The goals and objectives of the association were formulated by Alexander Benois as follows: “Coming out of our secluded cells into the public arena, we made a voluntary commitment to monitor what is being done and was done throughout the vast territory of the true ‘world of art’ in the present and past, to introduce the most striking and characteristic phenomena and to fight any undead.”

Certainly, like anyone who dared to rebel against the foundations and traditions, Diaghilev had to resist a barrage of criticism. The Mir Iskusstva was accused of mediocrity, declared a gathering of decadents, called a bunch of aesthetic clowns. This did not stop Diaghilev. He cajoled investors, fought with critics, quarrelled with Repin and Serov, quarrelled with his associates, organized exhibitions, edited the magazine, made peace with Repin and Serov, cajoled investors again and again. This non-stop, desperately non-profit activity bordered on missionary self-denial. However, Sergei Diaghilev had some self-interest: he invested his strength and resources not only in the formation of a new cultural environment, but also in his own name, reputation, and his insatiable ego.

A born promoter, Diaghilev even knew how to turn criticism to the benefit of his cause. Almost single-handedly, he turned the Mir Iskusstva into the most authoritative formation, which became a real milestone in the cultural life of Russia.

In 1903, at a general meeting in St. Petersburg with a huge number of artists from Moscow and Paris, it was decided to deprive Diaghilev of his “dictatorial” powers. It was the beginning of the end: Mir Iskusstva was another worthy venture ruined by democracy.

Diaghilev quickly realized that his ambitions extended beyond organizing art exhibitions. Together with Alexander Benois, he founded the Mir Iskusstva art association, and the magazine of the same name after it. The core of the association, in addition to Diaghilev and Benois, consisted of the same Dmitry Filosofov, Léon Bakst and Walter Nouvel. However, now no one doubted that the main driving force and the undoubted leader was Diaghilev.

Mir Iskusstva was conceived as an alternative — to the Academy, the Itinerants, everyone. The goals and objectives of the association were formulated by Alexander Benois as follows: “Coming out of our secluded cells into the public arena, we made a voluntary commitment to monitor what is being done and was done throughout the vast territory of the true ‘world of art’ in the present and past, to introduce the most striking and characteristic phenomena and to fight any undead.”

Certainly, like anyone who dared to rebel against the foundations and traditions, Diaghilev had to resist a barrage of criticism. The Mir Iskusstva was accused of mediocrity, declared a gathering of decadents, called a bunch of aesthetic clowns. This did not stop Diaghilev. He cajoled investors, fought with critics, quarrelled with Repin and Serov, quarrelled with his associates, organized exhibitions, edited the magazine, made peace with Repin and Serov, cajoled investors again and again. This non-stop, desperately non-profit activity bordered on missionary self-denial. However, Sergei Diaghilev had some self-interest: he invested his strength and resources not only in the formation of a new cultural environment, but also in his own name, reputation, and his insatiable ego.

A born promoter, Diaghilev even knew how to turn criticism to the benefit of his cause. Almost single-handedly, he turned the Mir Iskusstva into the most authoritative formation, which became a real milestone in the cultural life of Russia.

In 1903, at a general meeting in St. Petersburg with a huge number of artists from Moscow and Paris, it was decided to deprive Diaghilev of his “dictatorial” powers. It was the beginning of the end: Mir Iskusstva was another worthy venture ruined by democracy.

However, the director of the Imperial Theaters, Prince Volkonsky noticed the success of Diaghilev. Back in 1899, he appointed Sergei Pavlovich as an official for special assignments. And although two years later he was dismissed with a scandal without the right to enter the civil service, Diaghilev managed to become interested in ballet.

Russian Seasons poster, 1909. Valentin Serov

Attracted by theatre

In 1906, Diaghilev organized an exhibition of Russian art at the Autumn Salon in Paris. The success was tremendous, and soon, in the wake of Parisians’ interest in Russian culture, Sergei Pavlovich returned with Historical Russian Concerts. Concerts with the participation of Rimsky-Korsakov, Rachmaninov, Chaliapin, the “Boris Godunov” opera by Musorgsky — publc liked them all, but they turned out to be commercially unprofitable.

Diaghilev was quite indifferent to the box office success of his endeavours. He was much more interested in his own reputation and imperial splendour — how Russia looked in the eyes of sophisticated Europeans. But he had investors.

Therefore, since 1909, Diaghilev decided to focus on ballet in the Russian Seasons, which he considered democratic art.

“Both the smart and the stupid can watch the ballet with equal success — all the same, there is no content or meaning in it; and even small mental abilities are not required to perform it,” Diaghilev said.

The premiere of the ballet seasons turned into a triumph. “The red curtain rises over the holidays that turned France upside down and carried the crowd in ecstasy after the chariot of Dionysus,” Jean Cocteau wrote about it. Experiencing ups and downs, Diaghilev’s entreprise existed for 20 years. The enterprise almost collapsed next to immediately — in 1909, Diaghilev’s high patron, Prince Vladimir Alexandrovich, died, moreover, Sergei Pavlovich quarrelled with the ballerina Mathilde Kschessinska, who was the mistress of Tsarevich Nicholas, the future Nicholas II. The troupe was left without funding and without their rehearsal base in the Hermitage. But Diaghilev was unsinkable — a cunning fox, a born politician, he knew how to attract new investments, charm new patrons, recruit, and sometimes open new primas. During those 20 years, he raised the prestige of Russian ballet in Europe to cosmic heights. And he made “Ballets Russes” and “Diaghilev’s entreprise” synonyms.

Attracted by theatre

In 1906, Diaghilev organized an exhibition of Russian art at the Autumn Salon in Paris. The success was tremendous, and soon, in the wake of Parisians’ interest in Russian culture, Sergei Pavlovich returned with Historical Russian Concerts. Concerts with the participation of Rimsky-Korsakov, Rachmaninov, Chaliapin, the “Boris Godunov” opera by Musorgsky — publc liked them all, but they turned out to be commercially unprofitable.

Diaghilev was quite indifferent to the box office success of his endeavours. He was much more interested in his own reputation and imperial splendour — how Russia looked in the eyes of sophisticated Europeans. But he had investors.

Therefore, since 1909, Diaghilev decided to focus on ballet in the Russian Seasons, which he considered democratic art.

“Both the smart and the stupid can watch the ballet with equal success — all the same, there is no content or meaning in it; and even small mental abilities are not required to perform it,” Diaghilev said.

The premiere of the ballet seasons turned into a triumph. “The red curtain rises over the holidays that turned France upside down and carried the crowd in ecstasy after the chariot of Dionysus,” Jean Cocteau wrote about it. Experiencing ups and downs, Diaghilev’s entreprise existed for 20 years. The enterprise almost collapsed next to immediately — in 1909, Diaghilev’s high patron, Prince Vladimir Alexandrovich, died, moreover, Sergei Pavlovich quarrelled with the ballerina Mathilde Kschessinska, who was the mistress of Tsarevich Nicholas, the future Nicholas II. The troupe was left without funding and without their rehearsal base in the Hermitage. But Diaghilev was unsinkable — a cunning fox, a born politician, he knew how to attract new investments, charm new patrons, recruit, and sometimes open new primas. During those 20 years, he raised the prestige of Russian ballet in Europe to cosmic heights. And he made “Ballets Russes” and “Diaghilev’s entreprise” synonyms.

The gay deity

Sergei Diaghilev was gay. He recognized his homosexuality early and never resisted it — his first partner, apparently, was his cousin Dmitry Filosofov, this relationship arose when Diaghilev was 18.

In this context, many biographical details, such as the female arias that Diaghilev performed in his youth, the discussion with Alexander Benois, which developped into a sort of comic fuss on the grass, acquire a slightly different vein.

In today’s world, Diaghilev could make use of this feature. But in those days, different morals reigned, and homosexuality could become a serious obstacle to an artistic career. The most popular version explaining Diaghilev’s dismissal from public service portrays him in an almost heroic light: Diaghilev was allegedly fired due to the fact that he invited artists from Mir Iskusstva to design the productions. Other officials considered the works too avant-garde, and Diaghilev did not agree to compromise and slammed the door. There is another, more prosaic version: the authorities were furious about Diaghilev’s affairs with dancers.

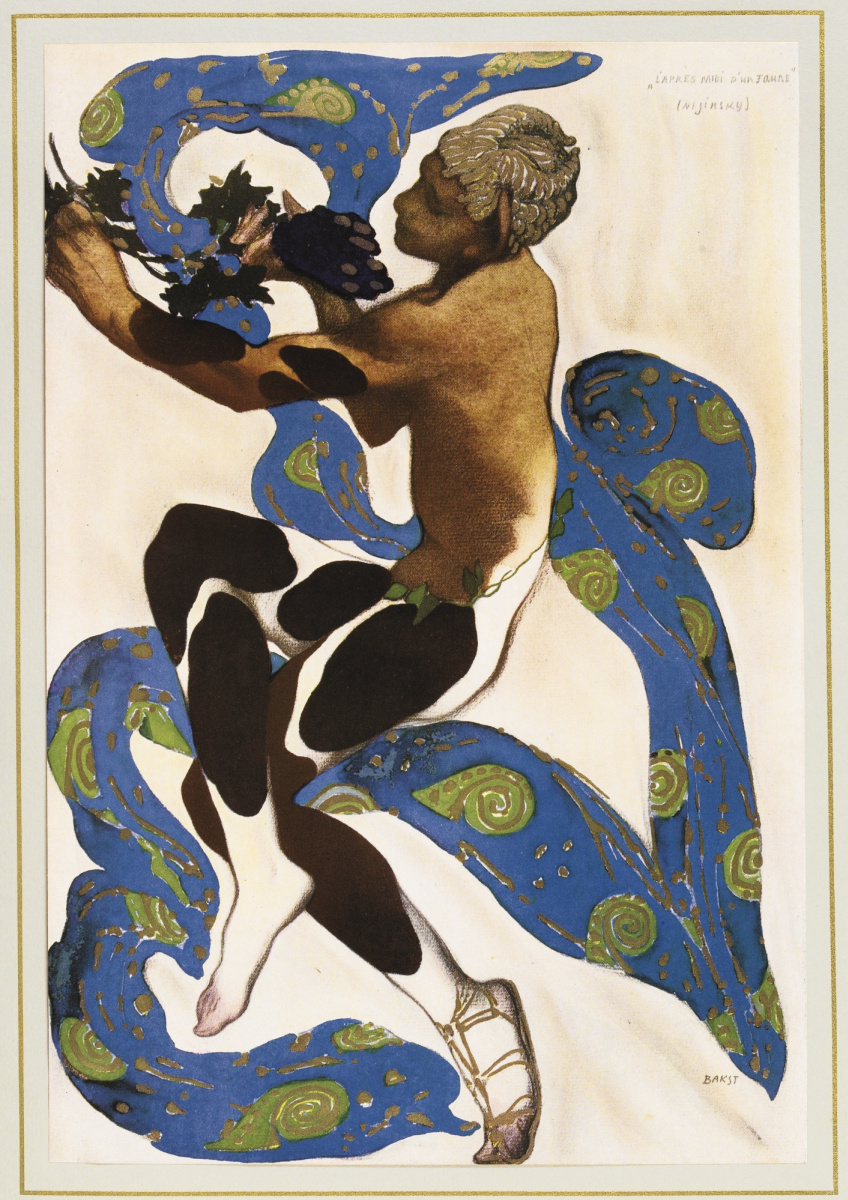

Over the 20 years of the existence of Russian Seasons and the Ballets Russes, the great impresario had many such affairs (with some of them being platonic). Diaghilev and his reputation were harmed by these affairs, whereas they acted as a powerful catalyst in the careers of his partners (among them, there were such stars as Vaslav Nijinsky and Serge Lifar). During their relationship with Diaghilev, they rose up in a creative sense and shone especially brightly. Diaghilev often hinted at his kinship with Peter I and tried to emphasize his resemblance to him in every possible way. But here, perhaps, a comparison with Catherine the Great is more appropriate — she also knew how to recognize and unleash the potential of her favourites.

In the end, the world had to reckon with both Diaghilev’s creative dictatorship and his sexual orientation. According to the composer Nikolai Nabokov, he became “the first great homosexual to declare himself and be recognized by society”.

An abstract society often did not know how to treat such an ambiguous character, as a great professional and devoted servant of art, a poser and an upstart, as a careerist or even a scoundrel, whereas the attitude of his artists was much more definite: Diaghilev was a deity for them. And, as befits God, he caused various, sometimes contradictory emotions and actions. They adored him. They were afraid of him. They revered, denied, regained him, were jealous of him. From time to time, they tried to crucify him — in the press or retroactively in memoirs and autobiographies. Having a reputation as one of the cleanest, regularly paying entrepreneurs, Diaghilev nevertheless became the object of financial claims. Everyone tried to get into his troupe. And yet, his artists were often unhappy, claiming that they were underpaid, that Diaghilev was an idle calculating businessman who used parasitizing their talent. This jealousy, of course, can be understood. Diaghilev, who never took a brush in his hands, played a crucial role in the history of Russian fine art. Diaghilev, who did not know how to make an entrechat, became the face, the driving force, the symbol of Russian ballet.

What explains the Diaghilev phenomenon? How the provincial, ridiculous Diaghilev, who tried to impress his friends with a fake pince-nez, turned into Diaghilev the “crusader of beauty” and the “Nero in a black tuxedo over flaming Rome”?

Diaghilev had a secret, but it was quite open. His initially condescending attitude towards ballet soon gave way to obsession. He worked like a navvy. Extremely sensitive to creative falsehood, during rehearsals, he did not spare artists, forcing them to repeat the same steps hundreds of times. He was no less demanding of himself — he came first, left last, sometimes did not leave at all.

As once at the Mir Iskusstva exhibitions, Diaghilev personally supervised all the nuances of the upcoming show, from choreography to the arrangement of seats in the stalls. The artistic component of Diaghilev’s performances is a separate topic. Illustrated programs, posters, costumes and sets created by Bakst, Benois, Matisse, Picasso — all of this was of its independent value. It happened that painting inspired, provoked by Diaghilev and his ballets, went beyond the scope of scenography. For example, the famous portrait of Ida Rubinstein painted by Serov, according to a version, appeared at the suggestion of Diaghilev, he conceived it as a promo for his seasons.

The incredible success of Diaghilev, his worldwide fame can be explained simply — he was a man of action. According to Alexander Benois, Diaghilev became a creator after he realized and accepted his mission. His mission was to say “Let it be” where others said “How nice it would be”.

Sergei Diaghilev was gay. He recognized his homosexuality early and never resisted it — his first partner, apparently, was his cousin Dmitry Filosofov, this relationship arose when Diaghilev was 18.

In this context, many biographical details, such as the female arias that Diaghilev performed in his youth, the discussion with Alexander Benois, which developped into a sort of comic fuss on the grass, acquire a slightly different vein.

In today’s world, Diaghilev could make use of this feature. But in those days, different morals reigned, and homosexuality could become a serious obstacle to an artistic career. The most popular version explaining Diaghilev’s dismissal from public service portrays him in an almost heroic light: Diaghilev was allegedly fired due to the fact that he invited artists from Mir Iskusstva to design the productions. Other officials considered the works too avant-garde, and Diaghilev did not agree to compromise and slammed the door. There is another, more prosaic version: the authorities were furious about Diaghilev’s affairs with dancers.

Over the 20 years of the existence of Russian Seasons and the Ballets Russes, the great impresario had many such affairs (with some of them being platonic). Diaghilev and his reputation were harmed by these affairs, whereas they acted as a powerful catalyst in the careers of his partners (among them, there were such stars as Vaslav Nijinsky and Serge Lifar). During their relationship with Diaghilev, they rose up in a creative sense and shone especially brightly. Diaghilev often hinted at his kinship with Peter I and tried to emphasize his resemblance to him in every possible way. But here, perhaps, a comparison with Catherine the Great is more appropriate — she also knew how to recognize and unleash the potential of her favourites.

In the end, the world had to reckon with both Diaghilev’s creative dictatorship and his sexual orientation. According to the composer Nikolai Nabokov, he became “the first great homosexual to declare himself and be recognized by society”.

An abstract society often did not know how to treat such an ambiguous character, as a great professional and devoted servant of art, a poser and an upstart, as a careerist or even a scoundrel, whereas the attitude of his artists was much more definite: Diaghilev was a deity for them. And, as befits God, he caused various, sometimes contradictory emotions and actions. They adored him. They were afraid of him. They revered, denied, regained him, were jealous of him. From time to time, they tried to crucify him — in the press or retroactively in memoirs and autobiographies. Having a reputation as one of the cleanest, regularly paying entrepreneurs, Diaghilev nevertheless became the object of financial claims. Everyone tried to get into his troupe. And yet, his artists were often unhappy, claiming that they were underpaid, that Diaghilev was an idle calculating businessman who used parasitizing their talent. This jealousy, of course, can be understood. Diaghilev, who never took a brush in his hands, played a crucial role in the history of Russian fine art. Diaghilev, who did not know how to make an entrechat, became the face, the driving force, the symbol of Russian ballet.

What explains the Diaghilev phenomenon? How the provincial, ridiculous Diaghilev, who tried to impress his friends with a fake pince-nez, turned into Diaghilev the “crusader of beauty” and the “Nero in a black tuxedo over flaming Rome”?

Diaghilev had a secret, but it was quite open. His initially condescending attitude towards ballet soon gave way to obsession. He worked like a navvy. Extremely sensitive to creative falsehood, during rehearsals, he did not spare artists, forcing them to repeat the same steps hundreds of times. He was no less demanding of himself — he came first, left last, sometimes did not leave at all.

As once at the Mir Iskusstva exhibitions, Diaghilev personally supervised all the nuances of the upcoming show, from choreography to the arrangement of seats in the stalls. The artistic component of Diaghilev’s performances is a separate topic. Illustrated programs, posters, costumes and sets created by Bakst, Benois, Matisse, Picasso — all of this was of its independent value. It happened that painting inspired, provoked by Diaghilev and his ballets, went beyond the scope of scenography. For example, the famous portrait of Ida Rubinstein painted by Serov, according to a version, appeared at the suggestion of Diaghilev, he conceived it as a promo for his seasons.

The incredible success of Diaghilev, his worldwide fame can be explained simply — he was a man of action. According to Alexander Benois, Diaghilev became a creator after he realized and accepted his mission. His mission was to say “Let it be” where others said “How nice it would be”.

Tableau

In 1921, Diaghilev was diagnosed with diabetes. Despite the warnings of doctors, Sergei Pavlovich refused to comply with the regime, neglected the diet. On the contrary, in the last years of his life he drank more than usual, became very stout. He did not like to lose, he simply did not know how to give up. Diaghilev continued to live as he was accustomed to — impetuously, in constant trouble, for wear and tear. The disease progressed.

In 1927, he developed furunculosis. The doctors feared that the case would end in sepsis — there were no antibiotics yet. Two years later, he was prescribed thermal water treatment. Diaghilev interpreted the prescription in his own way: instead of a trip to the Vichy water resort, he went on a “musical journey” along the Rhine. With his new (and last) protégé, the seventeen-year-old composer Igor Markevich, he visited Baden-Baden, Munich, Salzburg, Vevey. During the trip, Diaghilev listened to operas by Mozart and Wagner, cheered up, joked a lot.

In 1921, Diaghilev was diagnosed with diabetes. Despite the warnings of doctors, Sergei Pavlovich refused to comply with the regime, neglected the diet. On the contrary, in the last years of his life he drank more than usual, became very stout. He did not like to lose, he simply did not know how to give up. Diaghilev continued to live as he was accustomed to — impetuously, in constant trouble, for wear and tear. The disease progressed.

In 1927, he developed furunculosis. The doctors feared that the case would end in sepsis — there were no antibiotics yet. Two years later, he was prescribed thermal water treatment. Diaghilev interpreted the prescription in his own way: instead of a trip to the Vichy water resort, he went on a “musical journey” along the Rhine. With his new (and last) protégé, the seventeen-year-old composer Igor Markevich, he visited Baden-Baden, Munich, Salzburg, Vevey. During the trip, Diaghilev listened to operas by Mozart and Wagner, cheered up, joked a lot.

Sergey Dygilev and Leonid Myasin at the table

1910-mo

, 23×37 cm

In Switzerland, Sergei Pavlovich felt very bad. Having sent Markevich away, he left for Venice, where he summoned several close people by telegram. He stayed in bed for a week. He was looked after by a longtime friend and business partner Misia Sert, his assistant Boris Kokhno and dancer Serge Lifar (both more than friends). It seemed that everyone, except Diaghilev, had seen death at the head of the bed. Even the incurable disease could not break this restless person. With a temperature of over forty, half-delirious, he hummed something from Wagner and Tchaikovsky and made plans for the future. Diaghilev died on 19 August 1929.

In her memoirs, Misia Sert wrote: “…in the small room of the hotel, where the greatest art wizard had just died, a purely Russian scene was played out, which can be found in Dostoevsky’s novels. Serge’s death became a spark that blew up the long-accumulated hatred that the young men who lived next to him had for each other. In the silence, full of genuine drama, there was a growl: Kokhno rushed at Lifar, who was kneeling on the other side of the bed. They rolled on the floor, tearing, biting each other like animals.” They could not share their god even after his death.

Author: Andrii Zymohliadov

In her memoirs, Misia Sert wrote: “…in the small room of the hotel, where the greatest art wizard had just died, a purely Russian scene was played out, which can be found in Dostoevsky’s novels. Serge’s death became a spark that blew up the long-accumulated hatred that the young men who lived next to him had for each other. In the silence, full of genuine drama, there was a growl: Kokhno rushed at Lifar, who was kneeling on the other side of the bed. They rolled on the floor, tearing, biting each other like animals.” They could not share their god even after his death.

Author: Andrii Zymohliadov

The main illustration: Valentin Serov. Portrait of Sergei Diaghilev