Following Velázquez: Goya seeking his way

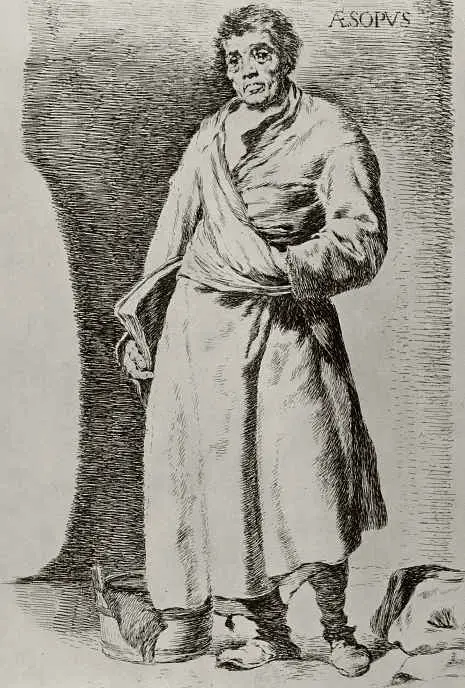

It is believed that the first truly original graphic works of Goya were Los Caprichos created in the 1790s. However, Goya began to look for his own style 20 years earlier, in the 1770s. At this time, he was an artist of the royal tapestry manufactory, made careful (maybe slightly exaggerated) graphic copies of paintings by Diego Velázquez "for himself".Why did he do it? Unlike many artists, Goya almost never theorized about art — his or anyone else’s. By nature, he was a practitioner and liked to repeat that he only recognized three teachers: Rembrandt, nature and Velázquez. Obviously, these were his universities.

The very career of Velázquez, who followed his way from the royal chamberlain to the quartermaster of the royal chambers and the main artist of the Spanish crown, at first seemed very attractive to Goya. In his youth, he consciously and consistently sought to ingratiate himself with the courtyard. And when, after many efforts, he received the title of court artist, he noted with satisfaction: well, now I am just like Velázquez!

The Álbum de Sanlúcar: Irrefutable Testimony

Goya’s romance with Duchess Cayetana Alba is not as accurate as the fiction assures us. Of course, Feuchtwanger’s novel Goya or the Hard Path of Knowledge and feature films about Goya are based on the love line of Goya, Alba. But these are a movie and a book. Science, on the other hand, sometimes doubts that a love story could really arise between people as dissimilar as the artist and the duchess.Goya was a baturro on his paternal side — in fact, a commoner, and the titles of María del Pilar Teresa Cayetana de Silva-Álvarez de Toledo y Silva-Bazán, Duchess of Alba took up half a page when written. Moreover, Goya was 20 years older. Middle-aged, heavy-tempered and completely deaf. It is unlikely, say those who question the very fact of the romance, that he could interest the widowed duchess who was always surrounded by admirers.

Skeptics have reasons: neither letters nor memoirs give sufficient grounds to say that the love affair between Goya and Alba really was.

However, on the picturesque portrait of Alba (under the feet of the duchess), the inscription ‘solo Goya' (‘only Goya') was found. But this ground is rather shaky for assertions. Perhaps this inscription is written later? And if not, perhaps it means something like "only Goya is the consummate master, whose brush is worthy to paint a magnificent duchess"?

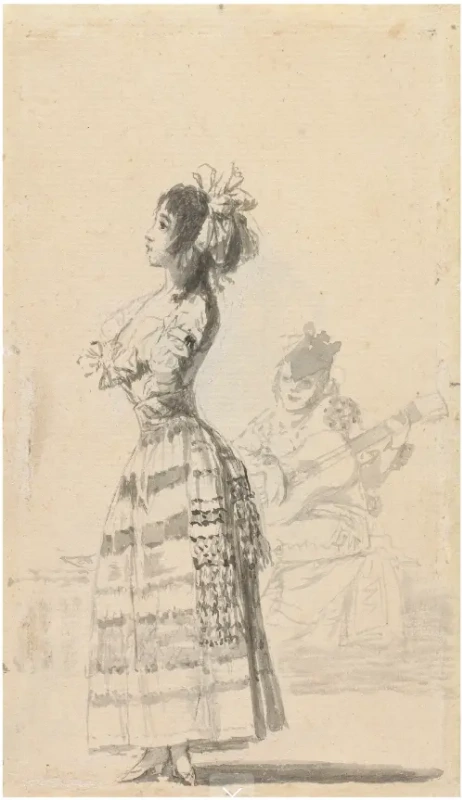

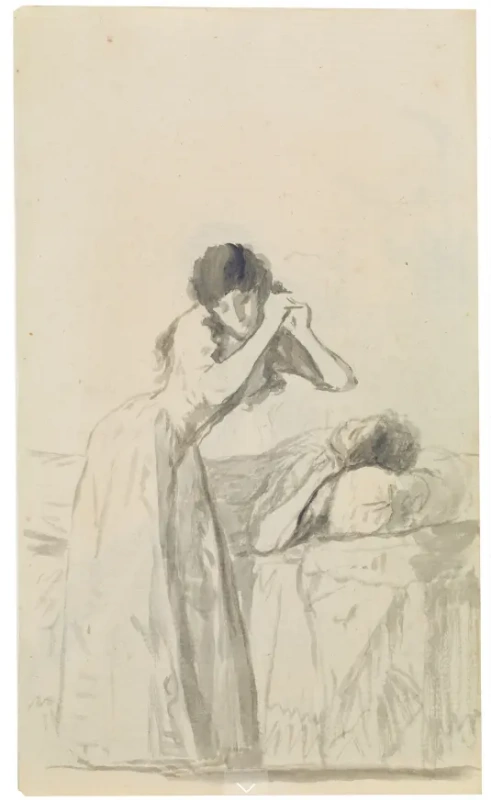

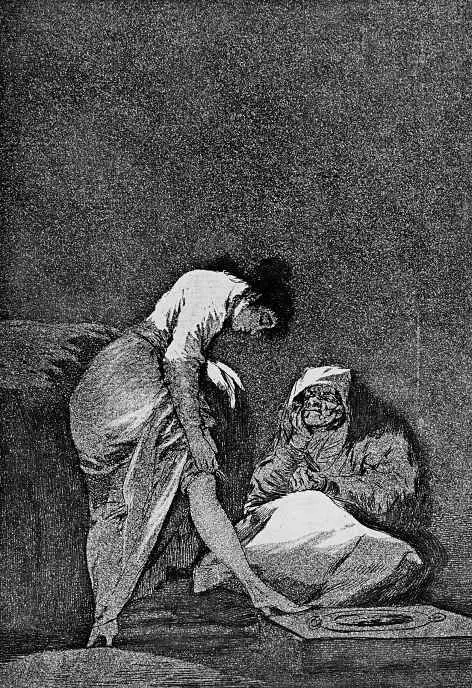

The artist did not stop painting. His album was so small (17.2 by 10.1 cm) that only one or two figures fit on a piece of paper. And often it was the figure of the duchess — or, to put it more carefully, someone extremely similar. In any case, a woman with a dark-skinned child on her knees is considered an indisputable portrait of Alba, the eccentric duchess took in little Maria de la Luz, whose parents were slaves; she became very attached to her and even left the girl an annuity in her will.

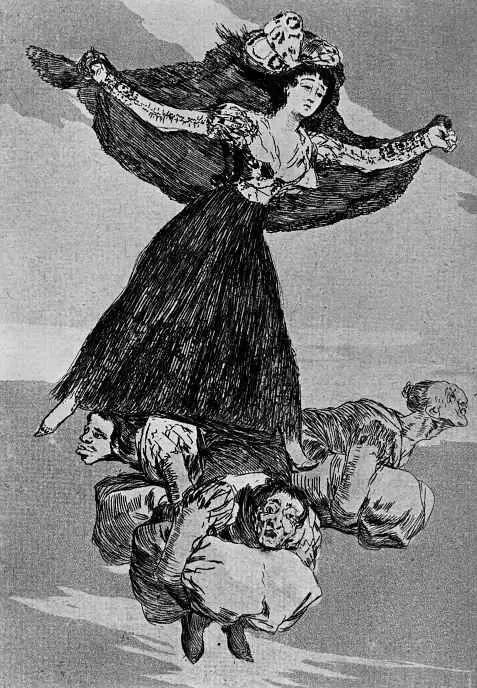

For example, what is she doing on this sketch? Is she drying and styling her wet hair? Or starting her favourite folk dance, shaking her bust hardly restrained with the corset? Clutching her head, she exclaims: "Blessed Virgin, why did Heaven send me this deaf jealous man?!" Maybe she just casts a spell for hair growth against the growing moon — for some reason, Goya portrayed her flying at night with witches.

On the side of the drawing is Goya’s note: "She is tearing her hair and stomping her feet because Abbot Pichurris told her she looked pale." There is so much admiration and tender irony in these letters that it is really easy to use it for a script, a romance, and a myth.

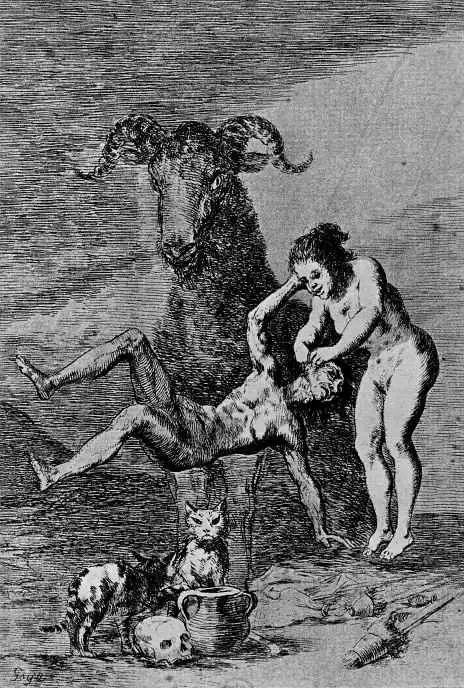

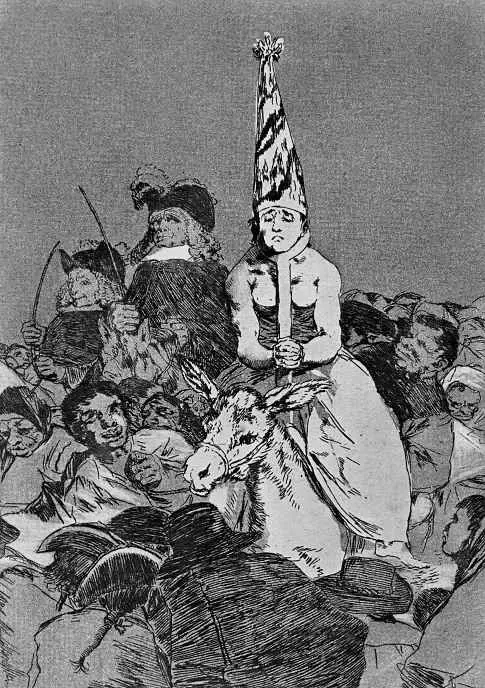

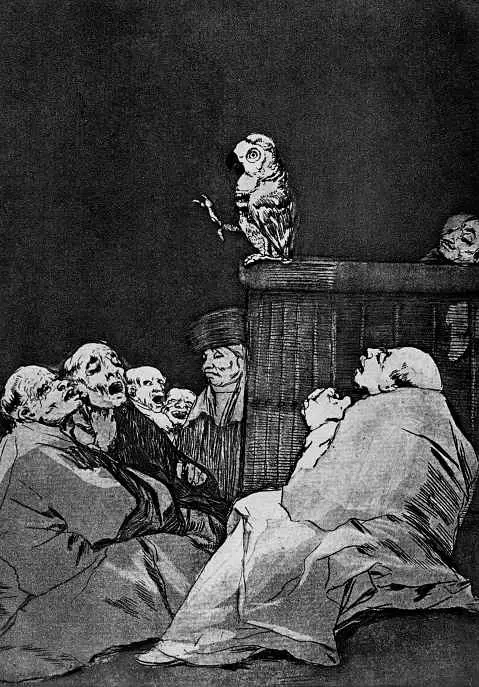

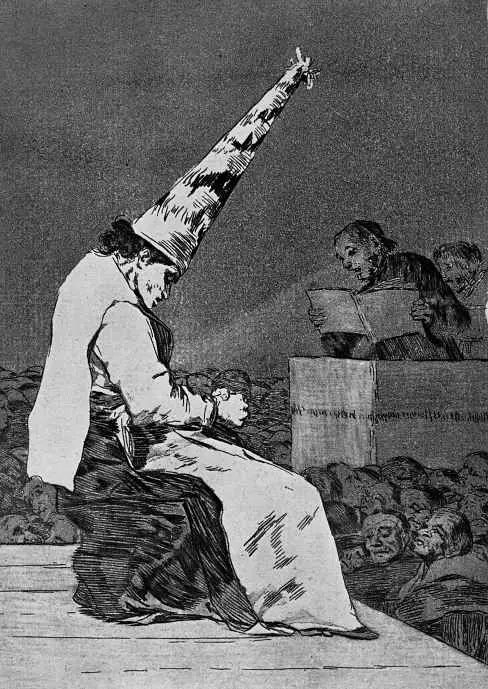

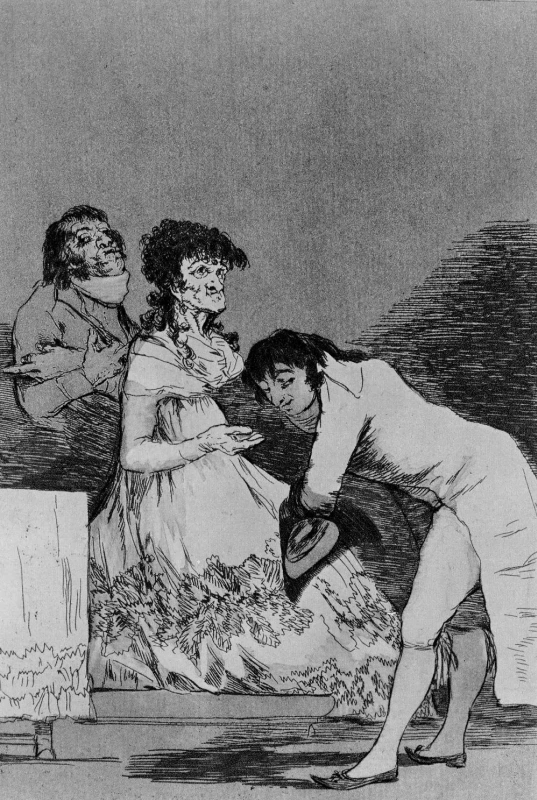

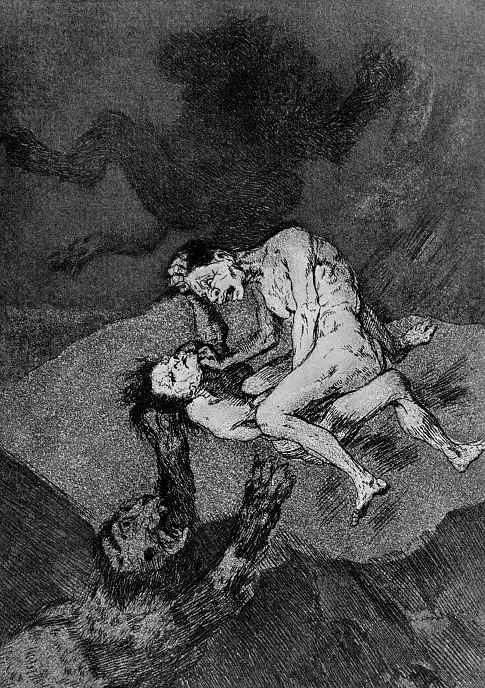

Los Caprichos: satire on thin ice

"Until the age of forty, Goya was a strong man, temperamental, sometimes unpredictable, he was a great lover of thrills, chocolate and partridge hunting," wrote art critic Pierre Gassier.

But why only until forty? And then what happened?

In the autumn of 1792, the 46-year-old artist leaves Madrid and travels to Seville. He takes off so suddenly that he doesn’t even bother to get permission from the king, his employer. Goya’s friends have to quickly sort out this difficult situation. And even now, this episode in Goya’s life remains one of the most mysterious ones. It is unclear what drove him away from the capital?

However, the fugitive did not make it to Seville. Feeling unwell, Goya stayed with his friend Martinez in Cádiz. The malaise, which began only with a "bad mood" and monstrous irritability progressed — severe headaches, tinnitus, darkening of the eyes and loss of coordination persisted. Goya lost the use of his right arm and got muscle cramps.

What was it? Diagnoses (viral meningitis, lead poisoning, complications of chronic syphilis, etc.) are only hypotheses for which there is insufficient data. But overall, Goya’s disease remains a medical mystery. It is known to have taken a long time to recover. The arm paralysis, fortunately, was temporary.

But something no less terrible happened: Goya became completely deaf.

It was a disaster. His former life was as if shamelessly kidnapped, thrown upside down, like the character of the etching of the same name.

It’s not just the disease. Remember that the relationship with Alba, full of jealousy and a consciousness of class inequality, did not add love to people either. In addition, Goya worked on the decoration of the palace of the upstart Manuel Godoy, the queen’s lover who usurped power in Spain — it is also a fair reason to be disappointed in humanity.

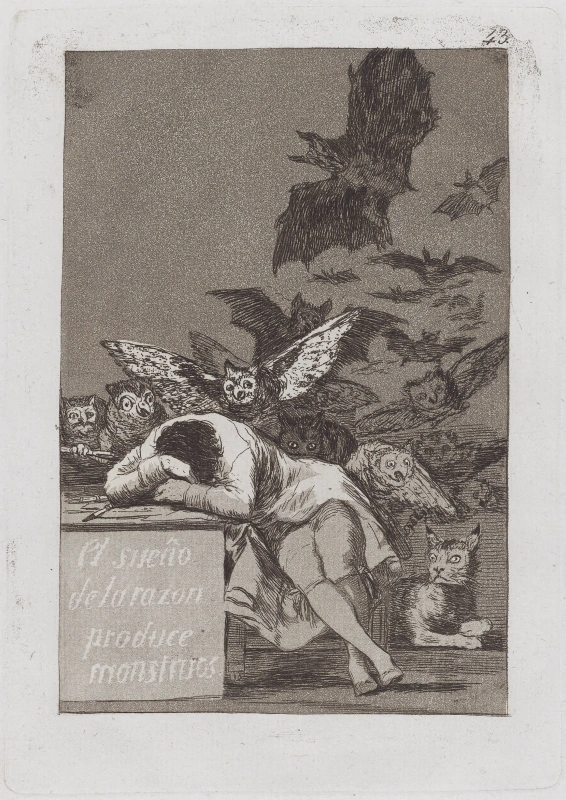

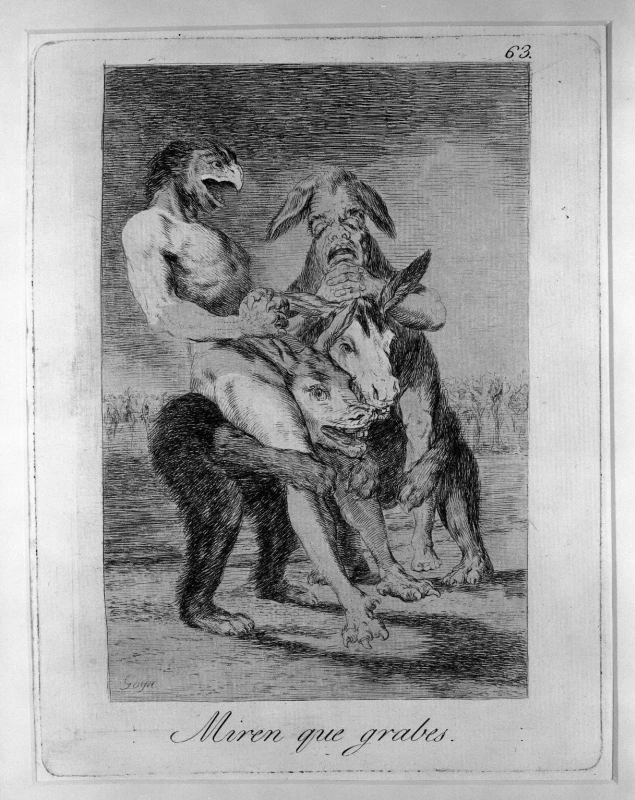

The logical end of this difficult life stage was Los Caprichos, the most famous series of etchings by Goya about how the sleep of reason produces monsters.

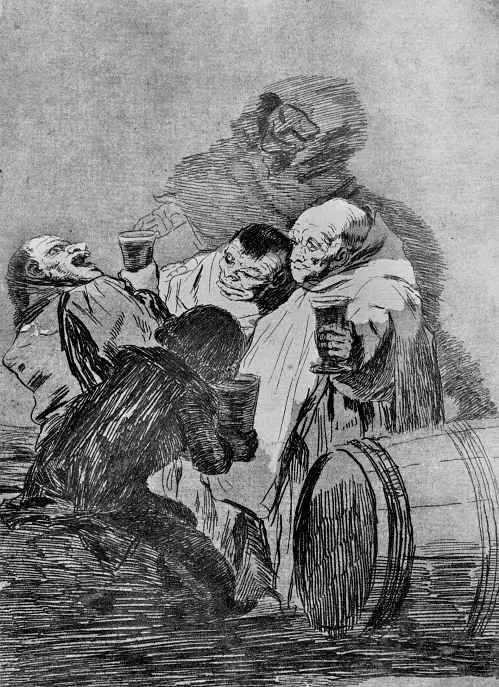

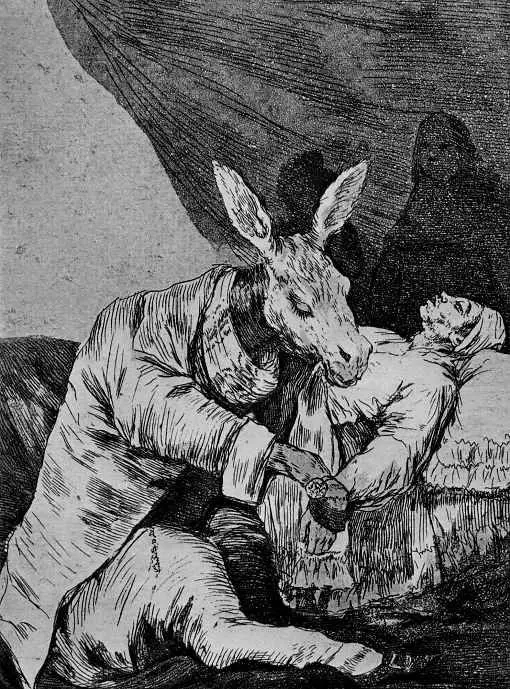

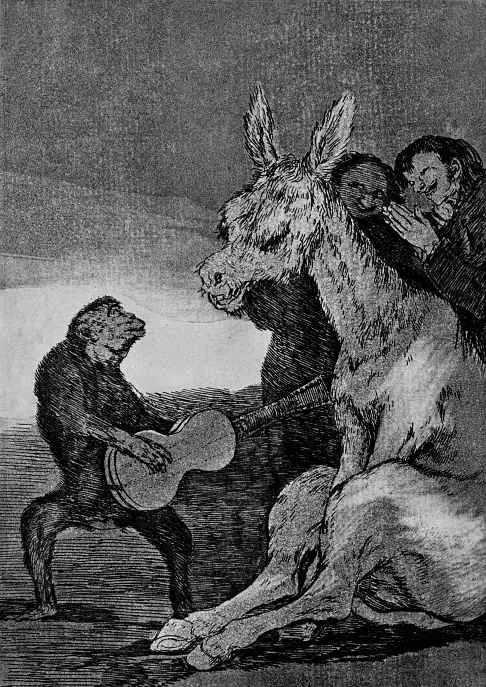

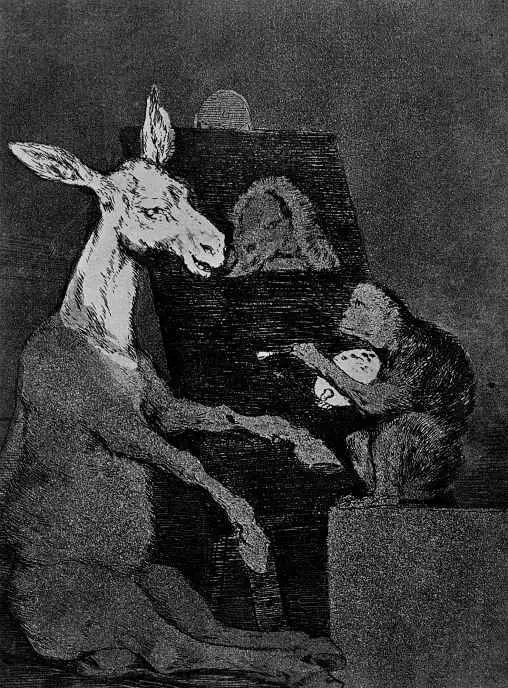

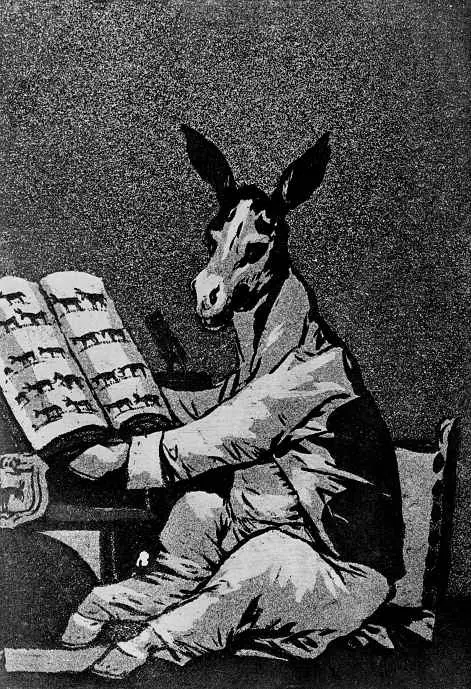

The name of sheet no. 50 of Los Caprichos is translated differently: Marmots, Hamsters, Sloths, although Goya called this etching Los Chinchillas. But animals are not depicted here. More precisely, not quite. We see two anthropoid creatures that may resemble the characters of some fantastic cartoons. Their eyes are closed voluntarily, and there are also padlocks on their ears, but they willingly open their mouths to absorb the brew given them by someone with a blindfold and donkey ears. Goya’s comment: "Those who do not want to know, see or hear anything belong to a large family of chinchillas (sloths, marmots, hamsters) who have never been useful for anything." But Goya could not know anything about such phenomena of the modern world as, for example, television propaganda or network "hamsters"!

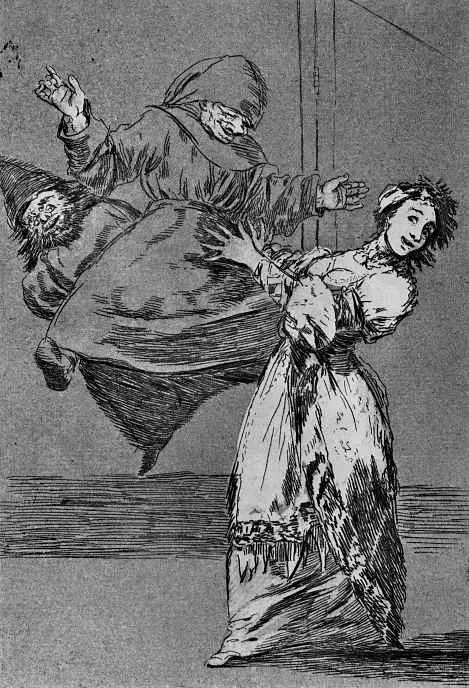

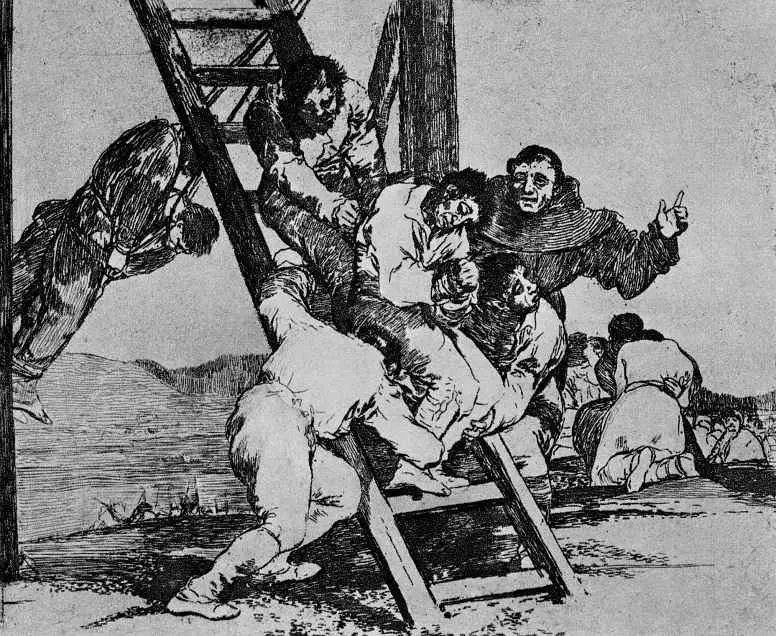

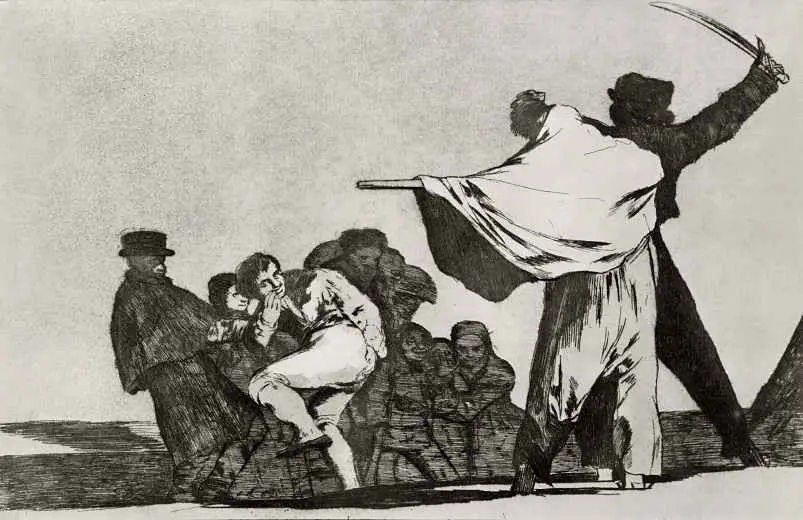

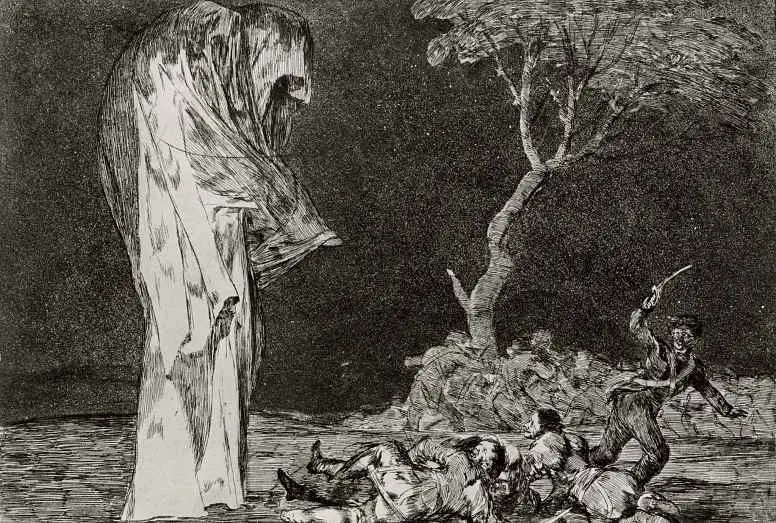

In the What a Tailor Can Do! etching, Goya depicts a crowd that, according to art critic Tatyana Kaptereva, "bow in fear before the formidable figure of a monk advancing on them, but this is just an empty cassock, put on a dry tree…, from the folds of the hood an eerie face of a ghost, formed by a pattern of tree bark, appears, vile creatures riding bats flock to him from the empty space of the bright sky".

Desastres (The Disasters of War)

Under one of the sheets of Desastres de la Guerra, Goya wrote the succinct famous: "I saw it".Spain, drained of blood by the civil war and the mediocre corruption rule of the Bourbons, fought for independence with Napoleonic France for six turbulent years. The temperament of Goya leaves no doubt: he was not a passive contemplator, although at that time he was already completely deaf and could not hear the guns firing and the shells exploding. Having learnt about the heroic defense of Zaragoza, led by Don José Palafox, Duke of Zaragoza, Goya personally rushed to Zaragoza and was under siege there — fortunately, not for long. And when the main pot of military operations moved to Madrid, he hurried there again. There is a legend that Goya watched the execution of the rebels directly from the roof of his house. The documents do not confirm this fact, but the myth turned out to be stronger than reality, the viewer is often sure that Goya was personally present at all military events.

Goya’s attitude to the French was not unambiguous, and this will be multiply reproached for him. He clearly sympathized with the liberal policies of Joseph Bonaparte (Napoleon's brother, whom he made king of Spain) and at the same time could not help but empathize with the Spaniards.

Goya wrote about the destroyed Zaragoza: "Seeing the ruins of the city, I began to study them in order to create paintings glorifying the city dwellers, I do not deny the enormous interest that arose in me for the glory of my fatherland."

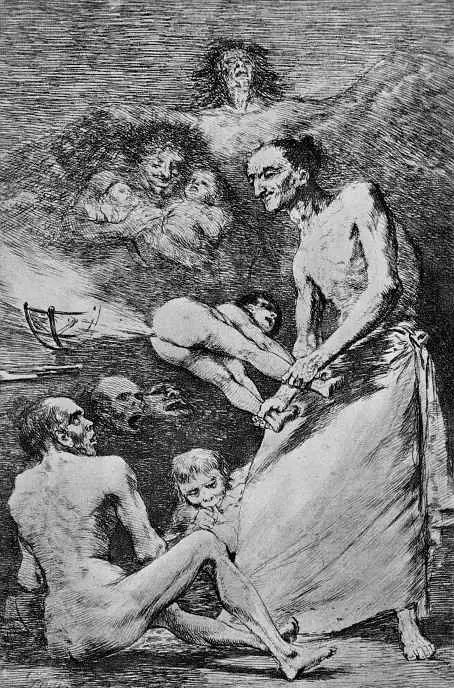

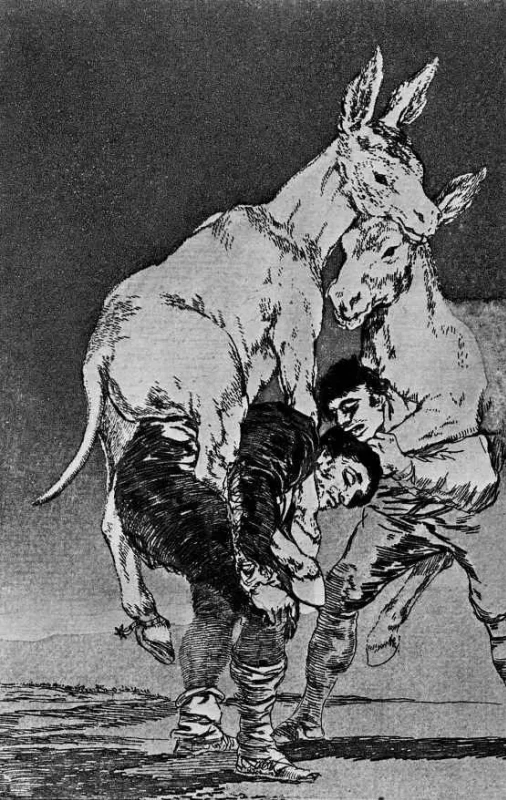

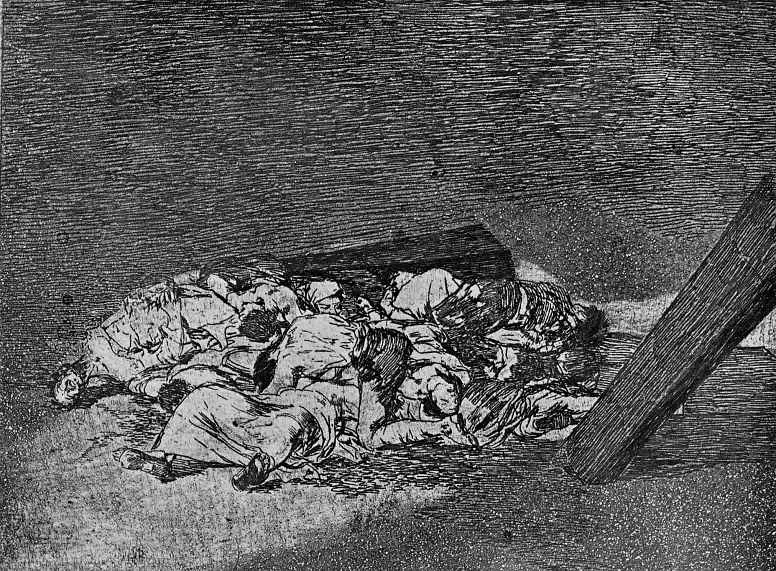

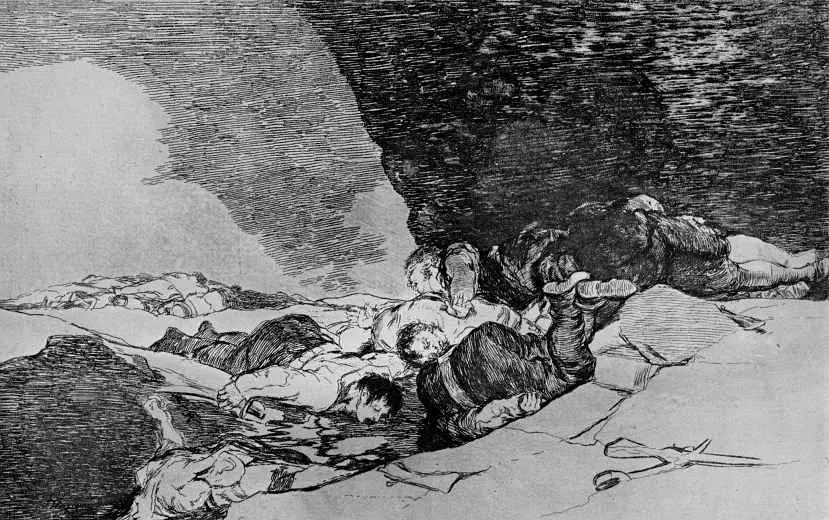

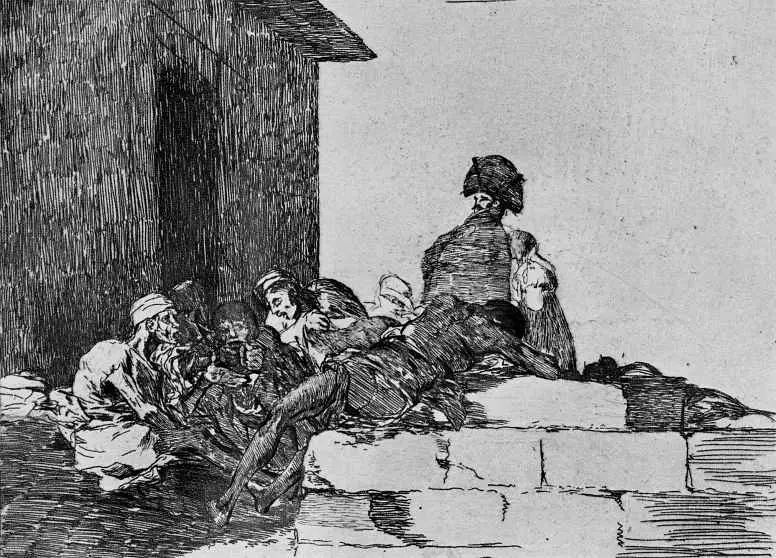

The Disasters of War is considered the pinnacle of the artist’s realism . They are painful to watch even today after the experience of dehumanizing art in the twentieth century. Goya is sometimes physiological, like a pathologist. He depicted executions, fires, looting, rape, hunger, corpses lying side by side (Pile of Bodies, The Same Elsewhere). People get shot, stabbed, chopped with axes and thrown off cliffs. The victims of the war are not only the military, but also children, women and the elderly.

La Tauromaquia

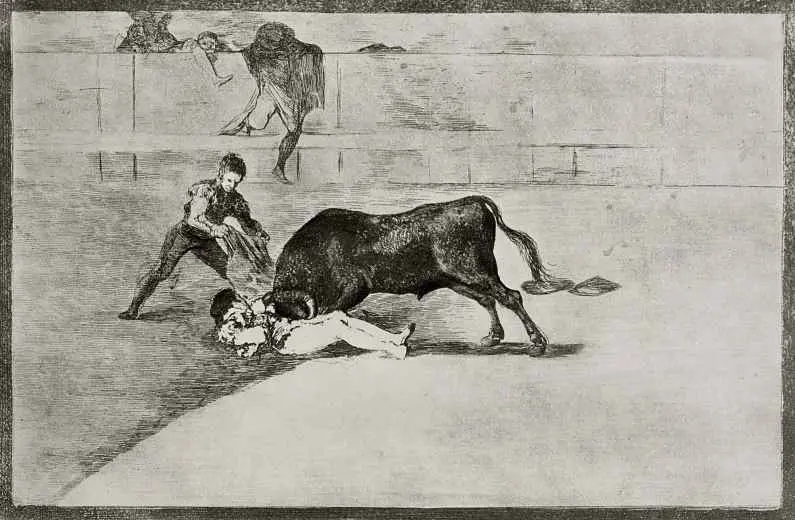

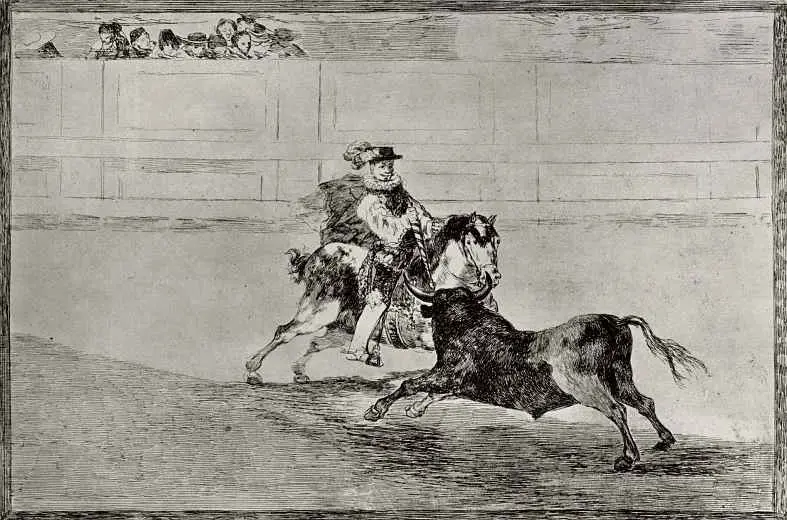

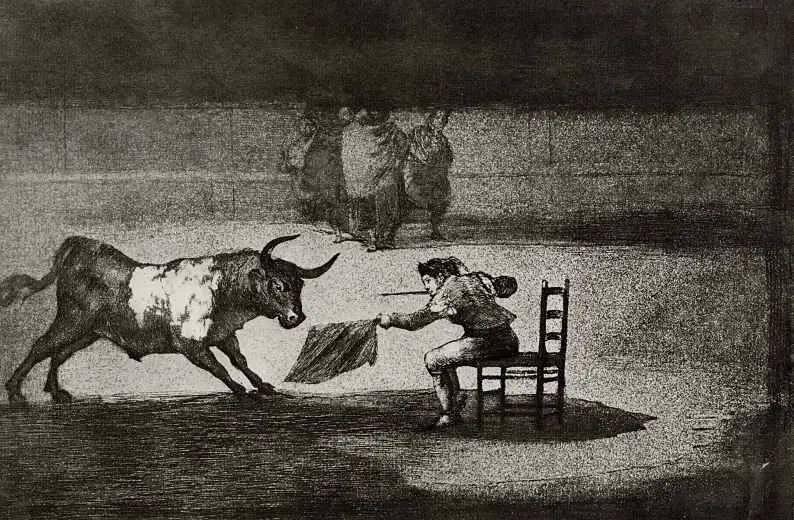

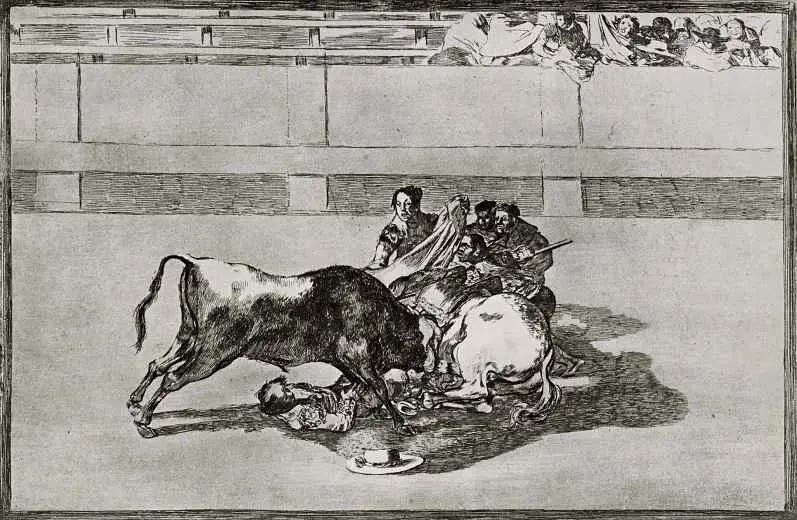

Goya turned 70 when in 1816, his La Tauromaquia etchings series was published, 33 sheets with scenes of bullfighting, very spectacular and dynamic. La Tauromaquia literally means bullfighting, but more often it is called History and Practice of Bullfighting.Working on La Tauromaquia, Goya even retreated from his dislike of theory: he closely studied the famous treatise by Nicolás de Moratín, Historical Letter on the Origin and Development of Bullfighting in Spain.

Bullfighting attracted Goya all his life. As a youth, to get to Rome, he joined a group of matadors heading for Italy. The bullfight, courage, the excited rumble of the crowd were his atmosphere. Sociable and cocky young Francho took part in bullfighting and performances of street acrobats himself. And then, having settled down, Goya never refused to watch bullfighting. Juanito Apignani, Rendon, Castelaro, Pajueler, Basque Martinico, Pepe Hillo were the big names of Goya’s contemporary bullfighters, famous throughout Spain. It is believed that Goya could see the death of Mariano Ceballos with his own eyes, a bullfighter who came to Spain from America. And he almost certainly saw Pepe Hillo die in the Plaza de Madrid.

But Goya looked at the bullfight differently: he was attracted by human courage and risk.

Goya was interested in technique of depicting a bullfight: how to convey the swiftness of an angry bull, the tension of a bullfighter, the crowd jubilant or holding their breath? The task was very difficult: both the bull and the bullfighter are in motion all the time, the angles are dynamically changing. To convey this movement is what can be considered the main technical task of La Tauromaquia, and Goya coped with it brilliantly, which put him on the verge of new time painting, without poses and statics.

Los Disparates (Madness)

On 27 February 1819, Goya bought the Quinta del Sordo estate — the House of the Deaf in a suburb of Madrid. The lonely deaf widower would paint the walls of his new villa with gloomy, frightening frescoes — they would later be called Black Pictures, transferred from the wall to canvas and transferred to a museum, and the house would be demolished in 1909.

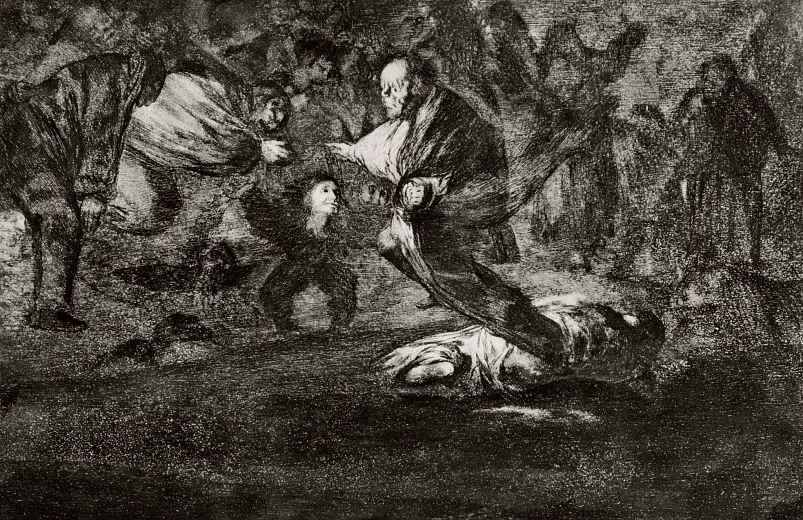

In parallel with the painting of the walls in Quinta del Sordo, Goya begins a graphic series, no less strange and mysterious than his Black Paintings. It is known by various names — Proverbios (Proverbs), Sueños (Dreams) or Los Disparates (Madness).

"Out of time and out of space," wrote Pierre Gassier about them, "Los Disparates become more and more human in their forms and as a clairvoyant, they conjure you from falling into the underworld."

![Francisco Goya. The Madrid album [20]: Nude model with a mirror, from the back, or After a bath Francisco Goya. The Madrid album [20]: Nude model with a mirror, from the back, or After a bath](https://arthive.com/res/media/img/oy800/work/d1b/220177.webp)