Goddesses and hunters

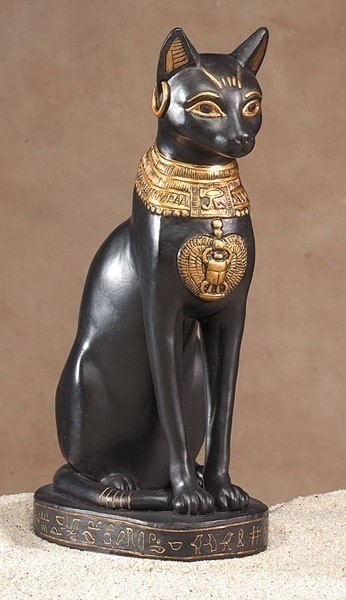

The predecessors of the lovely purrers were far from being sweet and friendly. One of the temples of Heliopolis had a sculpture of a cat — a personification of the sun god Ra portrayed as a wild feline. Depending on the time of day, the eyes of the statue narrowed or widened (the priests skillfully used the achievements of the latest technologies of the time), and every hour water flowed from the sacred animal’s mouth. Their stone sculptures followed the pharaohs to the afterlife and guarded them closely … however, their main security mission was to exterminate rodents who skillfully destroyed grain supplies. Due to their natural dexterity, those skillful hunters were elevated to the rank of gods, and therefore, their images had magical powers.

In Ancient Egypt, cats were everywhere: they were carved from stone, painted on dishes and walls of burial chambers, moulded out of clay… On the banks of the Nile, they were considered sacred, and those killing these animals faced death penalty. The whiskered assistants of the supreme deity were mummified and buried in special cemeteries.

In Roman and Greek painting, the images of cats could be found on coins, amphoras, beautiful mosaics, etc. However, they were not the "kings of animals", but only allies in the fight against rodents.

From heaven to hell

In the Middle Ages, when the Inquisition declared war on the chaos of unbelief approaching the world, cats fell out of favor. Thrown down from the throne, they were relegated for several centuries to the basement of human thought, and therefore — art. There was another reason for this: the religious nature of medieval painting caused each object in the picture to bear symbolic and ideological significance, each detail had a canonical meaning. And over the centuries, artists strictly observed the rules established by the church.

In the iconography of Christian art, our characters symbolized both laziness and lust, as well as deception and betrayal. In some medieval images, cats are even present in the scene of Eve’s fall from grace in the garden of Eden. But these are rare cases, since animals almost never appeared in the paintings of the artists of that time, with the exception of references to bestiaries (richly decorated compendium of information concerning certain animals, including mythical ones).

A suspicious attitude towards cats is also characteristic of the early Renaissance. For example, in his Last Supper, Domenico Ghirlandaio (1449−1494) painted the cat sitting behind the figure of Judas Iscariot, who betrayed Christ, thereby continuing the medieval tradition of hostility towards an animal, symbolizing betrayal in this story.

Images of cats also implied lust and in some cases referred to the world’s oldest profession. For example, in The Visit to the Spinner by Israhel van Meckenem (1495−1503), one can see a cat resting on the floor of the room where a young woman works at a spinning wheel, with a man seated nearby. It is believed that this painting depicts love for sale, and the presence of a cat indicates the purpose of the guest’s visit.

In the painting Birth of John the Baptist by Jan van Eyck the images of cats in the foreground are quite possibly the prophecies of future events: John the Baptist would be beheaded at King Herod’s banquet, visited by these animals.

The artists of the Renaissance for a long time did not depart from the canonical symbols and this can be seen in the triptych The Garden of Earthly Delights by the Dutch painter Hieronymus Bosch (1450−1516). In the foreground, near the Tree of Knowledge, God introduces Eve to the surprised Adam. As usual with Bosch, no idyll exists without foreshadowing evil, and we see a pit of dark water and a cat with a mouse in its teeth, which in this context symbolizes the devil and cruelty.

Painting a cat, Francisco Goya wanted to show its' predatory instincts (Manuel Osorio Manrique de Zúñiga. Boy, circa 1787).

Nature's masterpiece

However, the situation gradually changed: the shackles of religious prejudice weakened, life became more comfortable, and the mouse-catchers lying on the stove posed no threat, and even vice versa — they often were good company, and it was so pleasant to watch them in spare time!For the great Renaissance master Leonardo da Vinci, cats have become the object of scientific research. "The smallest feline is a masterpiece," wrote Leonardo, filling the pages of his album with sketches of these animals washing, playing or hunting mice and birds.

Usually, cats were painted next to children, and also complemented portraits and still lifes. They were not yet in the center of the composition, but already served as an important semantic detail of the work. In the portraits of young ladies, cats emphasized the femininity and tenderness of their owners, while static still lifes were supplemented with some kind of intrigue and action with the help of these playful creatures.

Often clever purrers were portrayed stealing food. However, it was done with humor and some admiration for the cats' dexterity and sagacity. As, for example, on the canvas of the Flemish painter Clara Peeters (1594−1657), who created several "genre" still lifes portraying charming cheats.

Cats in the house

By theBy the middle of the XVII century, cats had undoubtedly been recognized as part of the family (Louis Le Nain's Happy Family, 1642), and their images sometimes served as a metaphor for motherhood, a cozy home and liberties.

In England, cats were already in the pages of novels, poems and in pictures as an indispensable attribute of a happy family life.

In the middle of the XVIII century, animalism as an independent genre began the conquest of Europe. The famous English portrait painter George Stubbs (1724−1806), on his portrait of The Godolphin Arabian depicted animal friendship: the one between a horse and a cat.

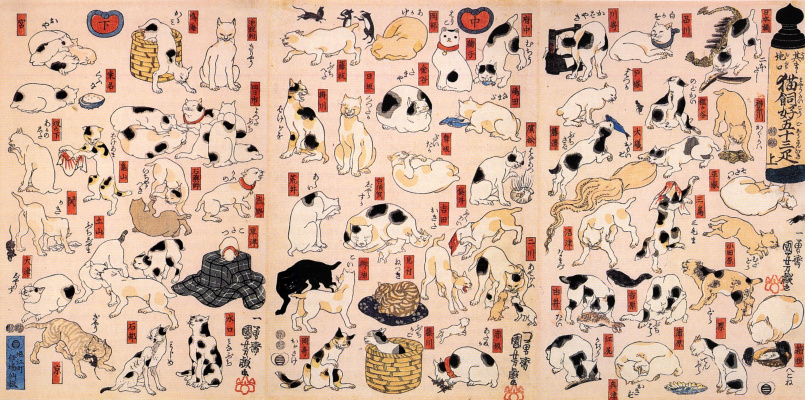

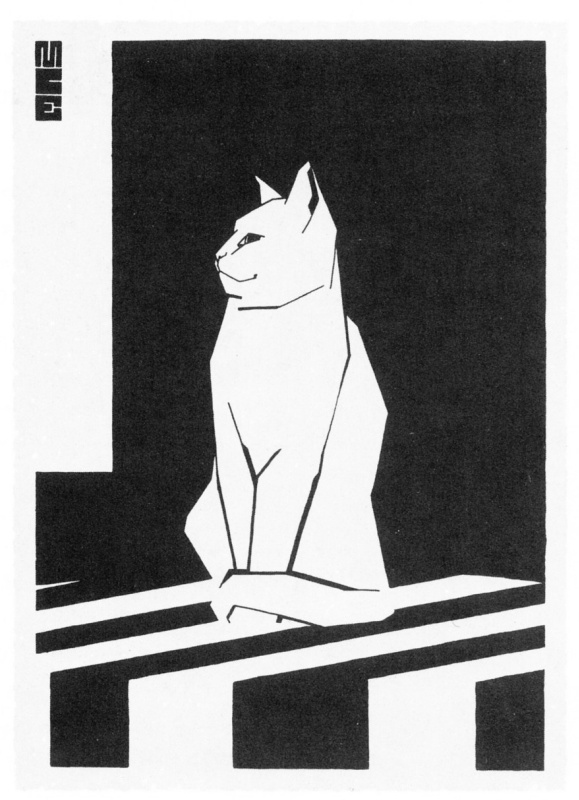

One of the most famous Japanese cat fans, Utagawa Kuniyoshi (1798−1861) and his woodcut print Cats Suggested As The Fifty-three Stations of the Tōkaidō are also a stark example of that. This is a parody of the famous series of woodcut prints The Fifty-Three Stations of the Tōkaidō. The whiskered cuties in this densely filled picture have punny names corresponding to the stations.

Catwomen, day and night

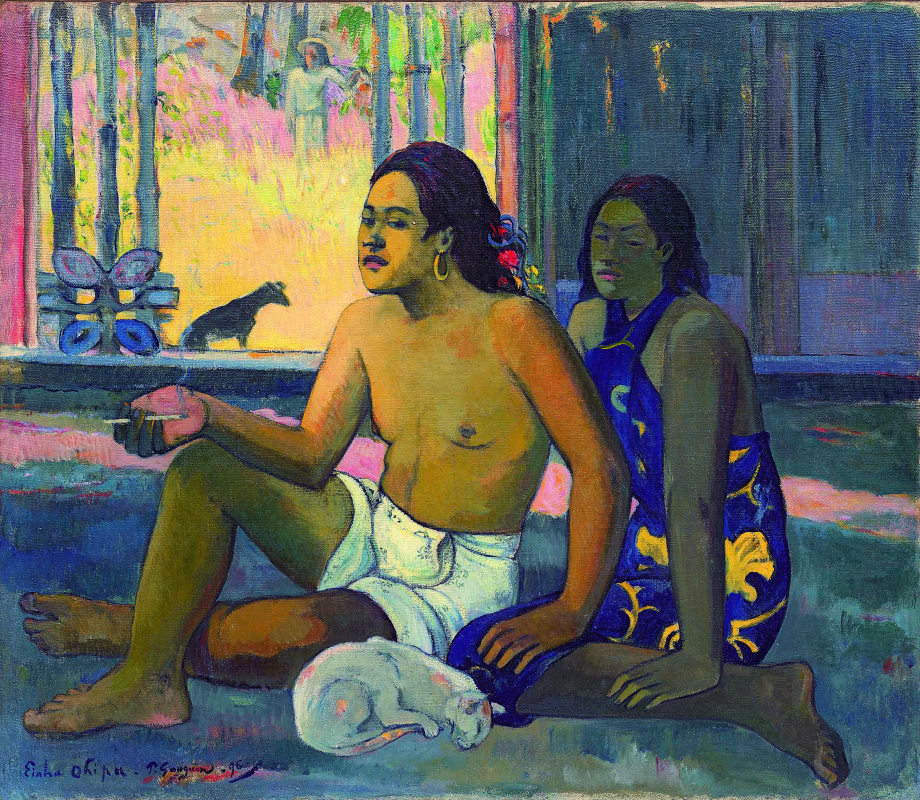

In the XIX century, artists no longer adhered to traditional symbolism and rather solved artistic tasks, using animals as an additional means to express emotions, emphasize the mood or aspects of personality of the characters depicted.However, the cats' dark past was not forgotten and their vicious nature was referred to by Édouard Manet (1832−1883) in his painting Olympia (1863). Painting a nude who had a black kitten by her feet, the artist conveyed the "catwoman" metaphor, inspired by the work of his friend Charles Baudelaire, who at that time was experiencing a difficult affair with a deceptive lady. The hissing kitten is a classic attribute in the images of the witches, being a sign of bad feelings and changeable female nature.

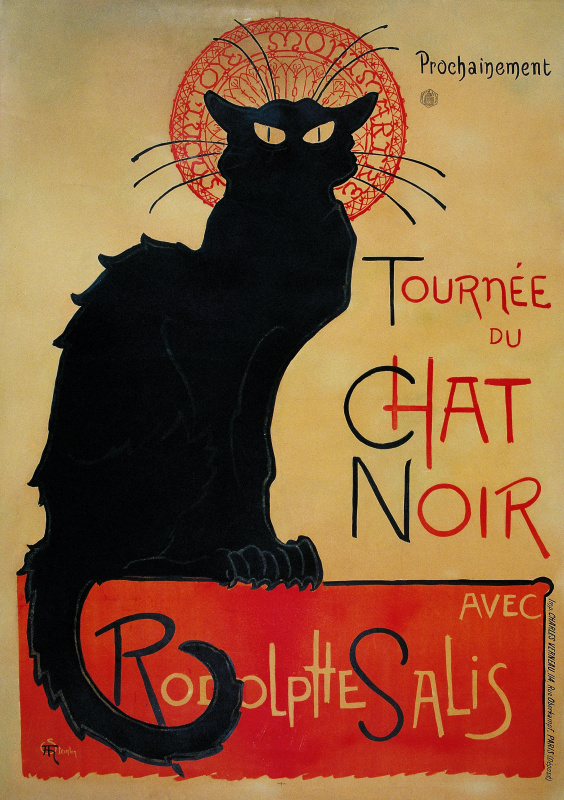

Another well-known work has already become a true symbol of Paris — it can be seen on T-shirts, bags, calendars … The cat on the cabaret poster by Théophile Steinlen (1896), the French graphic artist, the author of the album of picture stories entitled Cats, is a symbol of nightlife.

Entertaining felinology

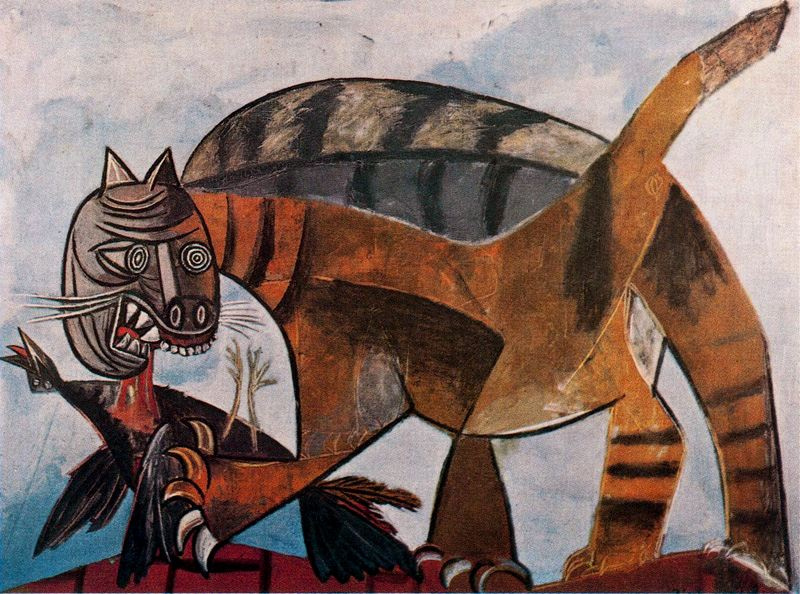

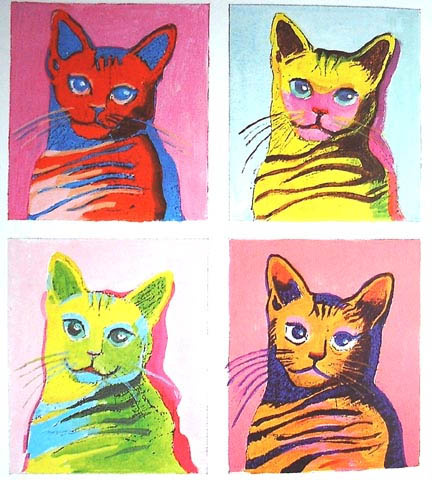

In the XX century, cats were no longer just participants in the genre scenes — their images became a safe marketing move, but the artist’s creative imagination would often endow them with human features and vice versa. For example, in Marc Chagall’s (1887−1985) famous painting Paris through the Window (1913), a red cat, sitting on the windowsill, has a human head. In his painting Cat Catching a Bird (1939), Pablo Picasso conveyed the animal’s predatory nature: extended claws and bare fangs, gripping a bird. It was the personification of the fascist threat emerging at the time.