Biography and information

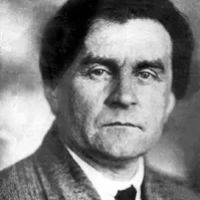

Kazimir Severinovich Malevich (February 23rd, 1879, Kiev - May 15, 1935, Leningrad) – Russian and Soviet avant-garde artist, founder of Suprematism, art theoretician, philosopher.

Peculiarities of Kazimir Malevich`s art: founder of Suprematism, world-famous for his Black Square, Malevich didn't restrict his art to the subjectless painting, having tried himself in almost every modernistic genres and styles that emerged at the turn of XIX-XX centuries (from Impressionism and Fovism to Cubism and Futurism).

Famous paintings by Kazimir Malevich: Black Suprematist Square, Red Cavalry Gallops, Self-portrait.

When the trees were green

Father of Kazimir Malevich, Severin Antonovich, was the manager of the sugar plants that belonged to well-known businessman Nikolay Tereshchenko. He was the man of the advanced views, a futurist in certain sense . He often took little Kazimir to the plants, where accompanied by mechanical clanging and crashing he explained that machines will rule the future. Severin Antonovich had no doubt that Kazimir will become an engineer or will hold the line becoming a distinguished sugar refiner.

Despite Severin`s profession, the Malevichs` life wasn`t sweet. They were not showered with riches; in addition, they often had to move from place to place. Kazimir grew up (by the way, the eldest of 14 children of Severin Antonovich and Ludwiga Alexandrovna Malevichs) in Ukrainian province: he lived in Podolia, in Bielopolie, in Konotop.

Hard as that is to believe, the future author of "The black square" was not a strange child driven to this world by the space wind. He was quite earthy boy — brisk and lively. He liked simple rural life. He enjoyed hot Ukrainian sunshine and beet fields, he adored hunting with a homemade bow and participating in the fights of the village and "the factory " boys, he was fond of "the objective".

Describing his childhood, Kazimir Malevich said that before he had not drawn at all until he was six or seven. He compared the impressions from the surrounding reality to the negatives awaiting development. Onсe, observing a painter coloring the roof with green paint, the young man experienced the enlightment — the paint was the same color as the trees. When the painter left for lunch, Kasimir climbed onto the roof and began to "represent trees". The trees were not quite good, but the feeling of the brush gliding over the red-hot roof was so pleasant, that there was nothing else the boy could think of. Passion for drawing took possession of him suddenly and forever.

He painted with ink, pencil, thick brush (bought at the pharmacy), homemade paints from clay and various powders.

Once (Kasimir lived in Bielopolie at that time) the artists from St.-Petersburg came to the town to work in a local cathedral. Together with his friend, the young man stood by the cathedral all day long to get a glimpse of these alien artists from another world. "We crawled in the most careful way, on the belly, with bated breath, — later Kazimir Malevich recalled. — We managed to creep up very close. We saw colorful tubes, it was very interesting to watch the artists pressing them... our excitement knew no bounds. We spent there two hours".

Seeing that his son was seriously carried away, Kazimir`s mother gave him real oil paints. Ludwiga Alexandrovna had a kind heart and a light hand. Once, she gave the violin to Nicholay Roslaviets, a neighbor boy from a poor family. He grew up and became a prominent composer, teacher, music theorist.

As for the Kasimir`s father, he painted a little — he was especially good at themes with goats. However, Severin Antonovich did not approve a career of an artist: he wanted his son to master «a decent" profession.»The artists are all go to prison" he repeated.

As it turned out later, dad had a point.

Kursk anomaly

In 1896, the Maleviches moved to Kursk — Severin Antonovich found a job in the local railway administration. There was also a job of a draftsman for the seventeen-year-old Kasimir there. It`s been a burden to him, and painting literally helped to brighten up the boring weekdays. One of his colleagues used to study drawing in Kiev. His another friend, who worked at the local alcohol purification plant, studied in the St. Petersburg Academy of arts for two years. Together, they formed the backbone of an improvised art society, which was soon joined by many colleagues, neighbors, friends and sympathizers. Even then, Kazimir Malevich showed one of his most important abilities, to infect others with his own ideas and lead. However, at that moment the idea was simple: to draw.

With the arrival of Malevich, the town of Kursk got its second anomaly, as for a certain period painting became an extremely fashionable and popular hobby. Seeing that the epidemic cannot be stopped, the authorities offered a room in the railway office to the artists, where they equipped their workshop. Malevich and his associates ordered literature and plasters from Moscow, canvassed the area in search of suitable nature, spent their savings on easels and paint. Eventually they even began to arrange annual exhibitions (those were the first in the history of Kursk), where not only railroad workers passionate for art participated, but also well-known artists from other cities.

"On the dim background of the Kursk existence our club was a real volcano of artistic life", Malevich recalled. Of course, local wives were not thrilled living on this "volcano". Observing their husbands indulge in this unusual hobby, forgetting about their home responsibilities and careers, they sighed: "He`d better drink and smoke."

Kazimir Malevich got married in 1901. Kazimira Zgleitz, daughter of a local doctor, was his choice. Soon after marriage they had a son, and a year later Kazimir`s father – Severin Antonovich - died of a heart attack. These events led to a paradoxical effect: as a senior man in the family, Kasimir suddenly felt free and headed for Moscow. "My friends were alarmed by this brave move - he wrote. - But their wives were extremely happy."

In favour of the revolution

Kazimir Malevich filed documents in the Moscow school of painting, sculpture and architecture four times, and each time he was rejected. He was not discouraged. He lived in the artists’ commune in Lefortovo, studied in the studio of Fedor Rerberg and in summers he returned to Kursk to earn. There wasn`t enough money not only to move his family to Moscow (the couple had their daughter born in 1905), but often even for food. According to the memoirs of Ivan Klyunkov (the artist`s friend, they met at Rerberg`s studio), once Malevich was taken to the hospital collapsing from hunger. As Kasimir showed absolute complacency in relation to "foody aspect", then energetic Ludwiga Alexandrovna took all the domestic issues into her hands. In 1906 she rented five-room apartment in Moscow, taking her daughters, grandchildren and daughter-in-law there. She also leased a canteen, but the family business was on the verge of collapse, after the canteen had been robbed by a hired cook. However, even in relatively prosperous times Kazimir Malevich continued to live in the commune, as he never was an exemplary family man.

Finally, Kazimira took the children and left.

Malevich continued to despise "foody business", embodying the classic image of a hungry artist. He frantically worked, considered himself a socialist, enthusiastically welcomed revolutionary events. Barricades beckoned him both in the streets, and in art.

Malevich joined the revolutionary movement in 1905, when (in his words) he fought for the Red Presnya with a revolver in his hand. Kazimir Malevich was never overly neat diarist, but there remains the fact: he definitely had acquaintances in the circles of professional revolutionaries.

As for the painting, then the events also developed rapidly and dramatically. Arriving to Moscow as an admirer of Shishkin and Repin, soon Malevich felt itching for reforms. Shortly he called Serov "incompetent brush pusher", Repin was described as "the captain of a blunt fire brigade, extinguishing everything new." He was friends with the bawlers-futurists, walked on the Kuznetsk bridge with wooden spoons in his buttonholes, wrote blank verse. However, unlike many of his colleagues, Malevich did not shock for the shock itself — he was looking for something instead. Sincere uneducated barbarian, seeing a strange trend in art, he rushed there like a big and strong child to a new toy. He challenged the durability, mangled, brought to the absurd, broke. In addition, having broken it, he was losing interest and moved on, always taking away part of the flock. And, of course, he carried some uprooted useful detail with hip. Each period in Malevich`s life enriched him with something, or even armed him. In the period of reverence for Repin (and later at Rerberg`s studio) he acquired technique. Dealing with Impressionism, he gained creative freedom. Violent epileptic colors were taken from Fauvism, and geometric austerity of lines and shapes - from Cubism. He borrowed the paradoxical logic of the illogical from Futurism. The list follows.

Later on, the master of hoaxes, Malevich will be transforming his creative biography to add the features of evolution: from Impressionism to his beloved brainchild — Suprematism. For this reason, for example, he dated his late impressionist works back to the early 1900s, so that there were no doubt that from the outset, he went forward and knew what he was looking for. Anyway, in 1915, he reached and found it.

Black square, red corner

In 1913 Malevich designed the futuristic opera "Victory over the Sun" — a sample of the pretentious and sheepish "new art", which is remembered solely because of its sketches and decorations. Among other things, Malevich depicted a black square on the backstage, which represented, roughly speaking, the technological triumph, the victory of the man over the nature, the man-made over natural, the rational over spontaneous the electric over solar.

The trial attempt went unnoticed.

Two years later Kazimir Malevich lit his black sun at full power, presenting the most famous of all his "Black squares" at the exhibition "0, 10" in Petrograd.

"Pictorial Manifesto of Suprematism," which was hung by Malevich in the red corner by no coincidence, was a sensation. He split reality into "before" and "after" The Square. This black hole has absorbed the other paintings by Malevich, some of them being much more interesting. Henceforth he was the author of the controversial avant-garde icon and no one other. The magic of The Square spread onto anyone. There were those who prayed in front of it, and those who cursed it. There were few who just passed by.

The excitement was supported by the fact that the exhibition "0, 10" was held in the atmosphere of not a friendly rivalry.

For all his originality, Kazimir Malevich was a clear-headed man. He harbored no illusions, knowing that many people could draw a black square (or a circle, or a cross). Having fumbled Suprematism, he formulated its laws and principles, and in the summer of 1915 he painted 39 canvases with the intention not to show them to anyone before the exhibition opening. The idea of "figurative painting" floated in the air, many of his adherents worked in that direction, thus to prove the authorship of a new movement an entire field would be difficult if anything.

Approximately three months prior to the exhibition "0, 10", its organizer, the artist Ivan Puni, dropped in to see Malevich. He saw everything.

Alarmed Malevich urgently wrote and published the article "From Cubism to Suprematism. New pictorial realism". In his letter to the publisher Mikhail Matyushin he asked "to christen it and to warn his copyright", telling him to tear the letter.

Finally the organizers forbade to use the word "Suprematism" not only in the title of the exhibition, but also in the exhibition catalogs. When his jealous colleagues Cubists got to know that Malevich henceforth intended to stand apart, they put the sign "Room of professional artists", showing Malevich his place of “an amateur”.

Anyway, Malevich remained in the art history as the inventor of Suprematism.

It was not just about vanity. Malevich knew that he had found something more than a new artistic movement — he created a new religion, new world order, a new way of communicating with the universe. Moreover, he felt his responsibility.

So what was revolutionary about Suprematism in general and “The black square" in particular? If we simplify to the limit, then it will be the notorious new sincerity, first of all. Its essence was sniper accurately formulated by Malevich`s biographer Ksenia Buksha. "When you draw me, then it's not me painted, but the drawing of me, — she writes. — When you draw a black square, it turns out the black square".

It was an attempt to put on a glass slide the very essence stripped of all excessive. The experience is definitely intriguing. It is also frightening in its finality. After all, if you win the sun, what should you do next?

It remained to explain, to teach, to preach.

Word and deed

It Was Malevich, who introduced the word "Suprematism" (from Latin suprem — supremacy). Originally, it meant the supremacy of color over the other elements. Later, there appeared another sense — domination over the other movements ,the peak of evolution in art. Subjectless geometric shapes, the color, existing by itself, the energy, born from their interaction, and nothing more. If Serov and others "incompetent brush-pushers" needed pink color to depict, for example, a peach, Malevich was interested in pink shimmer without peaches, girls, weight, morality, good, evil and other existential husk.

Kazimir Severinovich described the ecstatic experience during his work on The Black Square in a very peculiar verse: "There rushed millions of stripes. My vision was feeble not being able to touch the places around me. I could not see. The eye died in new glimpses". That is, the Suprematist had to become blind in some way in order to drill the universe with the intuition x-rays, ignoring the tricks of the mind.

Of course, his theories went far beyond art history.

In his work "Suprematism. The world as objectlessness or Eternal rest" Malevich wrote: "Enslaved by the idea of practical realism, man wishes to make the whole nature ideal for himself. Thus, the entire substantive, scientifically sound, practical realism and all its culture belong to the idealist of the ideas never feasible... Hence it is quite clear to me the storm of wrath and war, barbed wire, suffocating gas, suicides, weeping, gnashing, sadness and melancholy of the poets, artists, technicians – all those materialists seeking to catch the objectless and to embrace it into their physical arms."

It is hard to ignore the fact, that the ideas of Kazimir Malevich were largely in tune with the Buddhist beliefs. His educated companions pointed him out on some resemblance to the Eastern mystical and philosophical doctrines. He did not take it into account and boasted of his own definition of "the bookless", insisted that he could grasp everything on his own.

Speaking of Suprematism, Malevich studiously avoided the word "philosophy". Neither he used the label of "religion", because both were considered as purely substantive and "foody" manifestations by him.

It is easy to notice the contradiction between his words and actions. It seems that Malevich did not quite understand that by drawing the objectless he creates WORKS of art; that he explains the uselessness of logic by logic itself; that the Nature and the Cosmos do not need any propagandists; that Eternal rest does not fit along with bleachers and banners.

Whatever it was, under the new Soviet regime his energy and leadership qualities came to the court.

He was the Commissioner for the protection of ancient monuments and artistic treasures and the people's Commissar of the people's Iso Narcompros. He ran a workshop at Vitebsk Folk art school. He was a professor at the Kiev Art institute. He had direct relevance to the State Academy of Artistic Sciences, the State Institute of artistic culture) and a good dozen of no less monstrous Soviet abbreviations. It should be noted, that Malevich was not indifferent to all of them. In 1920 in Vitebsk, together with his students Malevich established the Molposnovis group (Young Followers of the New Art), which was soon reduced to Posnovis, and in a few days was renamed to Unovis (the Fouders of the New Art).

Malevich was not fond of the Soviet regime, he was, surely, well aware of its nature. However, the "objective" and "foody" issues hold him in their "physical embrace" — this had to be considered.

His cloudless relations with the Communist regime were darkened after his trip abroad. In 1927, Malevich, already a celebrity of world renown, travelled to Poland and Germany. His solo exhibition took place in Warsaw, and in Berlin he was offered a room at the annual Great Berlin art exhibition. In addition, Malevich stopped in Dessau, where he visited the Bauhaus.

The foreigners looked at him as being a prophet, catching his every word. "Oh, that's a wonderful attitude. Fame flows like the rain," Malevich wrote in his letters to home. The idyll ended after a letter from Leningrad, in which the artist Malevich was ordered to return home before the closure of the exhibition. According to a popular legend, he was arrested right at the station and questioned for 36 hours in a row. It went without complications then. But in three years Kazimir Malevich was arrested again as a German spy. He was lucky this time as well — he spent just a couple of months in prison. But this incident has made a painful impression on the artist. In addition, the Soviet government had diminished its favour to the avant-garde art; Lunacharsky wrote that the proletariat needs "healthy, strong, convincing realism" In short , Malevich, though, escaped with comparatively little blood, found himself on the sidelines.

Ecce Homo

Neither the paintings by Malevich, nor his theoretical works do not explain the permanent diversity of sectarianism around him — we cannot do without the attempts to outline "the objective" portrait in the manner of Serov or Repin.

There is no doubt that Kazimir Malevich had a powerful charisma. Uneducated, charmingly tongue-tied, he could inspire . There was so much energy in his clumsy verbal formulations, that his erudite interlocutors listened to him open-mouthed. For example, famous philosopher and literary critic Mikhail Gershenzon(with whom Malevich had intense correspondence) asked him not "to decorate the style", in order not to lose the primitive power of the mind.

Kazimir Malevich was very strong, both mentally and physically. He walked much, lifted heavy weights, loved to tell about his victorious fights in youth. However, it is impossible not to mention his another trait: Malevich loved to stretch the truth and had a sense of humor.

He was honest and consistent in his attitude to the "foody issues": for almost all his life Malevich barely made ends meet, yet never get discouraged. However, he was not an ascetic.

Malevich was married three times. His second wife Sofia Rafalovich died in 1925 from tuberculosis, leaving Kazimir a five-year-old daughter. His third wife Natalia Manchenko was 23 years younger, she stayed with Malevich till his last days. Malevich loved all his wives. He was told to get on with kids easily (his own and other people's as well), enjoying their company. However, one cannot name Malevich as an exemplary family man — the work was always in the first place for him.

Hot-tempered, devoted to his ideas, he easily found friends, disciples and followers. EIt was even easier to acquire enemies. His work is inseparable from his personality. Those who were trapped by his energy, were eagerly praying to The Black Square and its author. Those who were immune to Malevich`s hypnosis, did not accept his works, considering him an ignorant upstart and a profanator.

In 1933 Malevich was diagnosed with prostate cancer. He died two years later.

Kazimir Malevich was buried in a coffin designed by his pupils. The black square was painted on its upper side and the red circle was at foot of it.

Looking at Suprematist Malevich lying in this coffin, his eternal opponent, the avant-garde artist Vladimir Tatlin said, "He is pretending".

Written by Andrew Zimoglyadov

-

Artworks liked by1 053 users

- Artworks in 9 collections and 756 selections

-

Styles of artAbstractionism, Avant-garde, Expressionism, Fauvism, Futurism, Impressionism, Constructivism, Cubism, Art Nouveau, Neoclassicism, Post-Impressionism, Pointillism, Realism, Romanticism, Symbolism, Surrealism, Suprematism, Primitivism (Naїv art), Cubo-futurism, Neo-impressionism, Cloisonism, Neosurrealism

-

TechniquesWatercolor, Gouache, Collage, Lithography, Chromolithography, Oil, Pastel, Ink, Chalk, Tempera, Pencil, Feather, Coal, Graphite, Porcelain, , Stump, Lacquer, Wax crayon, Gypsum, Print, Overglaze polychrome painting, Pencil, Sticker, Photogravure

-

Art formsPainting, Graphics, Sculpture, Architecture, Poster, Drawings and illustrations, Design and applied art

-

SubjectsStill life, Landscape, Portrait, Nude, Architecture, Genre scene, Religious scene, Mythological scene, Interior, Urban landscape, Allegorical scene, Literary scene

-

Artistic associations

-

Learning1895 - 18961905 - 1911

-

Teacher

-

StudentsMore

-