A study is an exercise painting that helps the painter better understand the object he or she paints. It is simple and clear, like sample letters in a school student’s copybook. Rough and ready, not detailed, with every stroke being to the point, a study is a proven method of touching the world and making a catalogue of it. However, in art history, the status of the study is vague and open to interpretation. Despite its auxiliary role, a study is sometimes viewed as something far more significant than the finished piece. Then, within an impressive frame

, it is placed on a museum wall.

So, when does a study remain a mere drill, and when can we call it an artwork in its own right, full of life and having artistic value?

So, when does a study remain a mere drill, and when can we call it an artwork in its own right, full of life and having artistic value?

Staccatos, teapots, and harems

The terms derived from the French word étude (study) are used universally, and not only by artists and art historians. In schools of music, études are helpful for practising a legato, staccato, or spiccato, or when developing the swiftness of the fingers. An étude focuses on a particular technical skill and provides material for perfecting it.Young actors act out short episodes called scene studies in which they can be asked to portray anything, like a teapot, a flamingo, a ghost, or a balcony of a castle. Some scene studies help actors in learning how to adlib and be quick to respond when the performance suddenly runs off the track. In short, studies are for learning and memorising things.

In creative writing, a study is an exercise where you are given a philological task: to describe a landscape using only metaphors, or to think up a fictional creature, or to show the characters' mood through their behaviour. No plot, no suspense, no progress of events — just a drill for imagination.

Endgame studies are composed to train chess players. The arrangement of the pieces on the board represents an intermediate stage of a chess game. The player’s task is to find how to conclude the game in a particular way.

Above: Pages from Eugène Delacroix’s journal. 1832

When a painter is taking a trip, studies can become his or her travel journal, a depository for impressions to be used later, back in the studio. While travelling across Algeria and Morocco, Eugène Delacroix made ink and watercolour sketches, thus committing to paper, as well as to memory, extraordinary colour combinations, undertones, sunlit mosaics, translucent fabrics. If he had no time to watercolour his studies, he provided them with indications, like ‘lilacky purple sleeves, shoulders lilacky purple, stripes of tender violet on the chest.'

When a painter is taking a trip, studies can become his or her travel journal, a depository for impressions to be used later, back in the studio. While travelling across Algeria and Morocco, Eugène Delacroix made ink and watercolour sketches, thus committing to paper, as well as to memory, extraordinary colour combinations, undertones, sunlit mosaics, translucent fabrics. If he had no time to watercolour his studies, he provided them with indications, like ‘lilacky purple sleeves, shoulders lilacky purple, stripes of tender violet on the chest.'

The Russian painter Vasily Vereshchagin travelled around Central Asia, Japan, America, he visited the Caucasus and the Balkans. He did it all his life, as if to mark with his presence all trouble spots of his days. He would often go, as a volunteer and at his own expense, into the very heart of a conflict, or a conflict would start soon after his coming to a place. Kalmyk lamas, Japanese beggars, fakirs, dervishes, bashibazouks, frozen corpses, harem interiors, pillars and arches of temples — all these are present in Vereshchagin’s studies from his military and travelling experience. Modern museums have whole rooms devoted to the collections of works by Vereshchagin.

The Pope, Pushkin, and Marie de’ Medici

Perhaps, of all genres, likeness to nature is most important in portraiture. A gnarled tree or a gallant and muscular steed, do not care how you picture them. But a portrayed person has certain opinions and the right to pay nothing to the painter if the portrait is a failure.To spare a model the torturous hours of sitting for a portrait (especially when painting a pope, or a fidgety infanta, or a queen of France), a Renaissance or Baroque artist made but a quick study of face and body individualities. Besides, quite often the monarch’s features captured in the study needed further, and sometimes considerable, modifications — for courtesy reasons, and to conform to an artistic canon.

Peter Paul Rubens spent four years going between Antwerp and Paris after he had been commissioned with a series of large pictures of Marie de' Medici (see above), the mother of the ruling king Louis XIII of France. To Antwerp, Rubens would take the studies of his models, and back in Paris, he would show preparatory drawings and drafts of the future canvases. After having them approved, he would return next time with finished pieces.

Speaking of studies and drafts, both are elements of an artist’s preparation for painting a picture. Their purposes are quite different, though. A study is a snapshot of life made to understand an object’s behaviour, structure, colour, shape. While a draft is something more speculative, it is the painter’s vision of the composition, subject, layout of the main elements in the future work. A study is an impression and emotion, a draft is reasoning and knowledge.

The Demon Downcast

1902, 139×387 cm

Mikhail Vrubel's sketch for The Demon Downcast is an example of a draft, his idea of the composition of a painting-to-be.

When the Moscow painter Vasily Tropinin first met Alexander Pushkin, he made a study from life (left) for the poet’s portrait (right). No doubt, the study is less perfect compositionally and coloristically, than the final version, where we see a masterly portrayal of the grand, iconic Pushkin, a Byronic sort of person. However, literary scholars and historians never stop picking the study from among other works by Tropinin, hoping it will help them imagine what the non-iconic Pushkin was like, what he seemed to be at first glance. And it is very likely that he was just as in Tropinin’s study — with swift, restless eyes and mobile expressions, difficult to capture and bring to common standards.

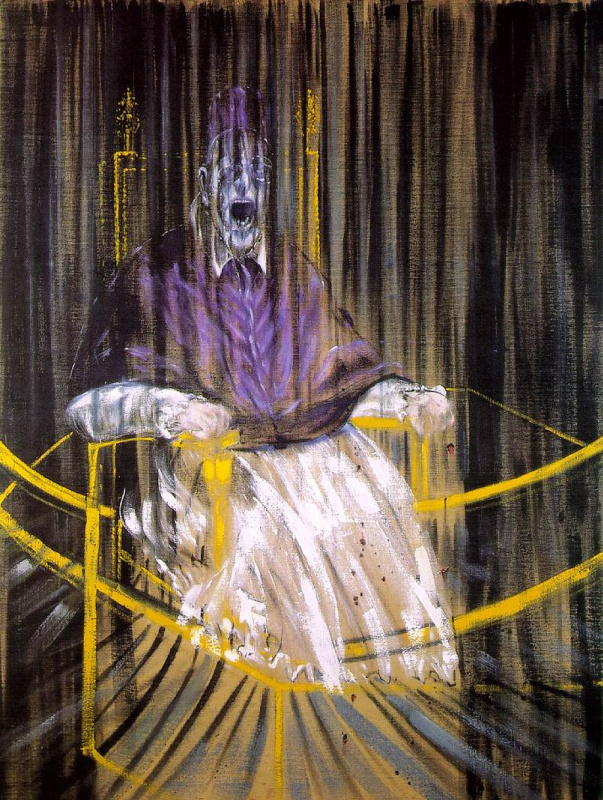

‘All too true!' exclaimed Pope Innocent X in admiration when he saw his portrait by Diego Velázquez. Though the preliminary study was made from life, the final portrait looks unfathomably more lifelike and richer in sense, due to its composition and elaborate textures. However, neither the features, nor the expression lost anything of their distinctiveness and character, being carried from the Pope’s audience hall to the painter’s studio.

Chopin, Stanislavski, and the Impressionists

In all arts (except chess, as it is not classed as an art), between the 1850s and the early 20th century, there were almost simultaneous changes in the status of the study.Frédéric Chopin was the first who composed short études (2 to 5 minutes each) that, although in conformity with the conventions of the genre, and still based on a limited number of playing techniques, were nevertheless highly emotional and difficult to play.

Sviatoslav Richter is playing Chopin’s two-minute Étude op. 10, No. 12 in C minor, called by Franz Liszt ‘The Revolutionary Étude'.

Later appeared études that were originally far beyond the limits of five-finger exercises, by Claude Debussy, Franz Liszt, Robert Schumann, Camille Saint-Saëns.

A veritable revolution in the name of the study took place in painting. Critics patronisingly termed the revolutionaries the impressionists. Everything that had been considered essential for a study — emotion, a momentary impression, transient, in-between states of nature, changes of mood, the model’s awkward posture — now became essential for art in general.

‘A preliminary drawing for a wallpaper pattern is more finished than this seascape!' exclaimed Louis Leroy, a critic. He was indignant at the outrageous incompleteness and the amateurish lack of subject in the pictures he saw at the First Impressionist exhibition. Academicians and critics believed that painting a picture should be a long and hard job, though with no visible traces of the effort. In their eyes, Claude Monet, Edgar Degas, Auguste Renoir, and artists like them were nothing but impostors who displayed their hasty sketches in the gallery and called them pictures, without even bothering to spread paint over some patches of bare canvas.

A veritable revolution in the name of the study took place in painting. Critics patronisingly termed the revolutionaries the impressionists. Everything that had been considered essential for a study — emotion, a momentary impression, transient, in-between states of nature, changes of mood, the model’s awkward posture — now became essential for art in general.

‘A preliminary drawing for a wallpaper pattern is more finished than this seascape!' exclaimed Louis Leroy, a critic. He was indignant at the outrageous incompleteness and the amateurish lack of subject in the pictures he saw at the First Impressionist exhibition. Academicians and critics believed that painting a picture should be a long and hard job, though with no visible traces of the effort. In their eyes, Claude Monet, Edgar Degas, Auguste Renoir, and artists like them were nothing but impostors who displayed their hasty sketches in the gallery and called them pictures, without even bothering to spread paint over some patches of bare canvas.

Claude Monet painted series of pictures, working on 20 to 30 canvases in parallel and trying to register the faintest changes in nature. He intentionally ignored, even defied the traditional principles of composition. In his works, the main character could seem to be tumbling out of the frame

, the figures could herd together at one side of the canvas, leaving a gaping void at the opposite side. Towards the end of the 19th century, there remained only one criterion, very fine and incalculable, to distinguish between a study and a finished painting — the ability to raise emotion, which was only characteristic of a completed picture, not a study.

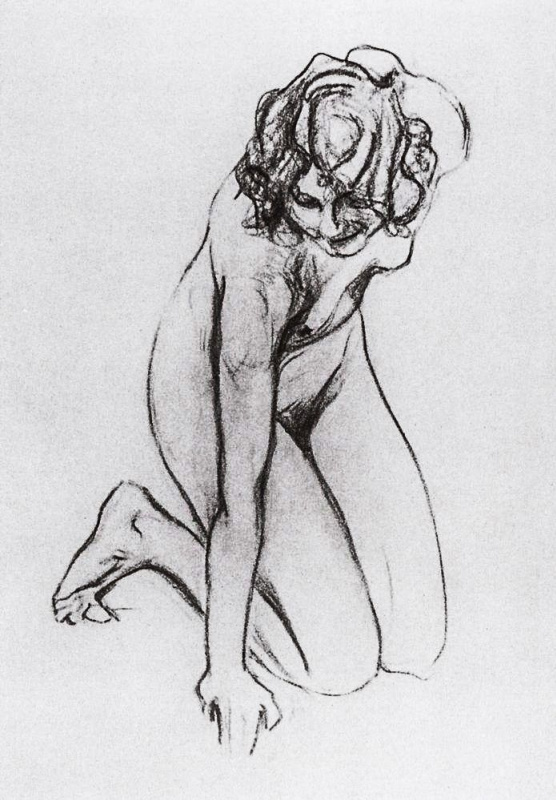

Valentin Serov had a special sketchpad for his studies and sketches. Its pages were sheets of tracing paper. After making a few minutes' sketch of a model, he immediately laid the next page above. The sketch showed through from underneath quite clearly, so Serov drew four or five more variants, removing all irrelevant details until the very essence remained in the final drawing.

In the early 1900s, Konstantin Stanislavsky introduced the term scene study into drama training. For the whole Western theatre, it marked a revolutionary era. His studies (with tasks like keeping silence in a natural way, or creating a certain atmosphere, or manifesting a state of health, or using metaphors) were aimed at making actors less rational, at stimulating their spirit and emotion.

The Pope again

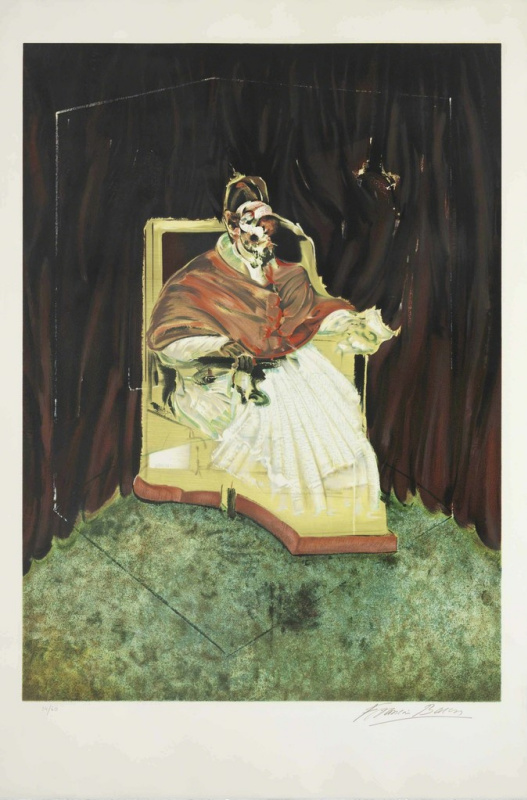

Paul Cezanne, while working on The Large Bathers in the 20th century, did not make studies of nude models. He joked that at his age one had an obligation not to make a woman undress to paint her. But the sketches he made as a young man were quite enough for the purpose — in fact, he did not need any models. He just strolled about, breathed the air, and watched the places he knew by heart.Francis Bacon, an artist of our time, re-interpreted Velázquez's Portrait of Pope Innocent X in a series of works which he defined as studies. However, they are not ones. The inexplicitness and lightness of a traditional study are gone to give way to carefully designed, intentional incoherence.

Thus, in the 20th century, a study, though still called by its name, is void of its essence. Now, it can be made not from life, but from another picture. Often, it is a mere play upon genres, with no other rules, but formal similarity.

Opening illustration: Paul Signac. Sunset over the City. A study

Text: Anna Sidelnikova

Text: Anna Sidelnikova