Degenerate Art

How Hitler got rid of "dangerous" paintings, "crazy" artists and unreliable art movements

The story of one exhibition, which became the most visited one in the twentieth century, drastically changed the lives of several dozen artists, deprived German museums of priceless collections, added the word "degenerate" to the dictionary of art terms and became a symbol of ruthless censorship in Nazi Germany.

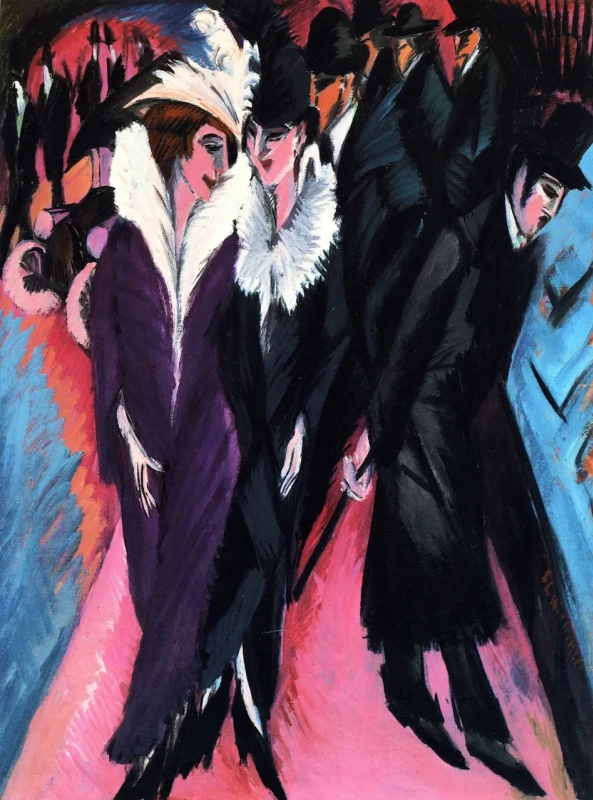

The Degenerate Art exhibition was opened on the second floor of the old Institute of Archaeology building in Munich on July 19, 1937. The exhibition included 650 works of art, confiscated from 32 German museums. The main purpose of the exhibition was to demonstrate and ridicule art that did not fit into the ideals of the new German society, defamed religion and the German nation, illustrated the degradation of an individual and was created by Jewish or communist artists. The list of "condemned" works included not only paintings by young German expressionists, dadaists and surrealists, but also works of the artists who by that time had already become recognized classics: Lovis Corinth, Vincent van Gogh, Auguste Renoir and Paul Gauguin.

Love – Hate

From the age of 13, Adolf Hitler dreamed of becoming an artist, during his school years he always received excellent marks in drawing, made several attempts to enroll in an art school and later applied to the Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna. Having failed the exams, he did not give up on his dream and worked as an artist for several years: created small paintings with views of historical buildings in Vienna, got a dealer, sued him, won and began selling paintings himself."As a young man in Vienna I once saw a Grützner in the window of an art dealership — very similar to this one," said Hitler, pointing at the picture of an old monk. "I timidly entered the shop and asked how much the painting costed. It turned out that the price was much more than I could afford. God, I thought, would I ever be able to achieve such success in life so that I could afford a Grützner?

Twenty-five years later, Hitler owned a collection of about thirty masterpieces by Grützner." This story was recorded by Hitler’s personal photographer Heinrich Hoffman.

Indeed, several decades later Hitler could afford not only a Grützner. His personal collection consisted of several thousand works that were purchased with funds from sales of his book Mein Kampf (My Struggle). And we talk about millions here. Eduard von Grützner, noted for his genre paintings of drinking monks, and Carl Spitzweg, a self-taught artist from Munich, who painted more than a thousand idyllic pieces about touching city dwellers, were central figures in Hitler’s personal collection. Of course, he idolized Dürer, ancient sculptors and Dutch classics, considered realistic and romantic scenes from the life of German cities and villages beautiful. He loved giving paintings from his own collection to his assistants, ministers and heads of various departments, ingeniously selecting the plots depicted so that they matched the addressee’s occupation. The painting was considered a painting only when it had a clear subject.

Adolf Ziegler was Hitler’s favourite contemporary artist. There were three of his paintings in the Führer's collection. The allegory Four Elements hung in Hitler’s library above the fireplace. Strong nude

women symbolized four elements — fire, earth, water and air — and at the same time embodied all the canonical ideological virtues: fortitude, health, tranquility and impersonal, cold beauty.

In his book of memoirs about the Führer, the same Heinrich Hoffmann mentioned the irritation that Hitler felt towards any incomprehensible art: "I cannot abide slovenly painting," he used to declare frequently, "paintings in which you can’t tell whether they’re upside down or inside out, and on which the unfortunate frame-maker has to put hooks on all four sides, because he can’t tell either!"

In the 1930s, Germany became a country in which Adolf Hitler decided which art was useful to the German people, and which one — destructive. But it still remained the country in which Kandinsky painted his First Abstract Watercolour, and Paul Klee — Twittering Machine, in which László Moholy-Nagy built his Light-Space Modulator, four students from Dresden came up with Expressionism, and in which the architect Walter Gropius founded the most influential school of art, architecture and design Bauhaus. And Hitler started thoroughly "fixing" these annoying moments in the history of German art with the same obsessive confidence with which he caused ethnic and racial lapses in the history of mankind. The sky in the painting had to be blue, the grass — green, men and women had to demonstrate calmness, fortitude and harmony. Everything else was a product of a sick mind. For the sake of the nation’s health, it was necessary to destroy all those libels to the beautiful German world, and preferably — together with their authors, as the insane ones and unworthy to pass their poisoned genes onto their offsprings.

In the 1930s, Germany became a country in which Adolf Hitler decided which art was useful to the German people, and which one — destructive. But it still remained the country in which Kandinsky painted his First Abstract Watercolour, and Paul Klee — Twittering Machine, in which László Moholy-Nagy built his Light-Space Modulator, four students from Dresden came up with Expressionism, and in which the architect Walter Gropius founded the most influential school of art, architecture and design Bauhaus. And Hitler started thoroughly "fixing" these annoying moments in the history of German art with the same obsessive confidence with which he caused ethnic and racial lapses in the history of mankind. The sky in the painting had to be blue, the grass — green, men and women had to demonstrate calmness, fortitude and harmony. Everything else was a product of a sick mind. For the sake of the nation’s health, it was necessary to destroy all those libels to the beautiful German world, and preferably — together with their authors, as the insane ones and unworthy to pass their poisoned genes onto their offsprings.

Adolf Hitler at the Degenerate Art exhibition, 1937. Photo source: jewishnews.timesofisrael.com

Place in history

In June 1937, a special commission led by Adolf Ziegler was charged with purging German museums of unacceptable art and had to confiscate all the paintings created by cubists, surrealists, dadaists, expressionists and even impressionists in the last fifty years. If the directors of the museums showed discontent — they were immediately replaced by other, more appeasable ones. After they removed more than 20,000 "degenerate" works from German museums, the holdings were first stored at the former granary in Berlin. Delirious plans to immediately burn, destroy and get rid of everything, were gradually replaced by common sense and the ideas that that colourful fuel could bring extra money.Nearly 4,500 of those works were selected for sale at auctions in Switzerland and transferred to a baroque castle not far from Berlin. Among these works there were paintings by Modigliani, Picasso, Derain, van Gogh, Klee and Kokoschka. "It will give me great pleasure if you succeed in replacing Picasso or Pechstein with Dürer and Rembrandt," Hitler told the commission members. Representatives of the best museums of Europe and America participated in the Swiss auctions: works, which seemed invaluable for many of them, were often sold by German authorities for a song. Pierre Matisse, the art-dealing son of Henri Matisse, came to Lucerne in Switzerland to purchase his father’s work. Some lots were sold for $10 or 1 Swiss franc! However, some museums ignored this unprecedented opportunity to get hold of a few dozen masterpieces as a matter of principle, because they didn’t want to have anything to do with a distraught dictator.

But before getting rid of the confiscated paintings and sculptures, the German authorities decided to demonstrate to the people how art had bottomed out over the years of decline. It took a special commission only 3 weeks to select 650 works of avant-garde artists for an exhibition, which was called Degenerate Art.

Before the riddance

The building of the Institute of Archaeology was divided into 10 small rooms, made of temporary partitions; the paintings were crowded together, usually hung by cord from floor to ceiling. Under each painting, there was a label indicating the name of the author, the title and the sum money a museum spent to acquire the artwork. Given the post-war hyperinflation and the following monetary reform, the old prices looked fantastic.Entrance to the exhibition was free of charge, so that everyone had the opportunity to have a closer look at the dying evil, which the German people would soon get rid of. Viewers had to reach the exhibit by means of a narrow staircase, which caused constant queues at the entrance. The first three rooms were grouped thematically: the first room contained works considered demeaning of religion; the second one featured works by Jewish artists; the third one contained works deemed insulting to the women, soldiers and farmers of Germany. The rest of the exhibit had no particular theme, many works were partially covered by derogatory slogans, which left the visitor in no possible doubt of how to perceive the exhibition. "The ideal — cretin and whore" was broadly painted on one of the exhibition walls. "Madness becomes method" — on the second one. "Nature as seen by sick minds" - on the third one. And finally: "Revelation of the Jewish racial soul." There were a lot of similar mocking slogans.

At the entrance of the Degenerate Art Exhibition in Munich, 1937. Photo: www.moma.org

Paintings Ecce homo by Lovis Corinth and The Tower of Blue Horses by Franz Marc in the halls of the Institute of Archaeology building, 1937. Photo: www.moma.org

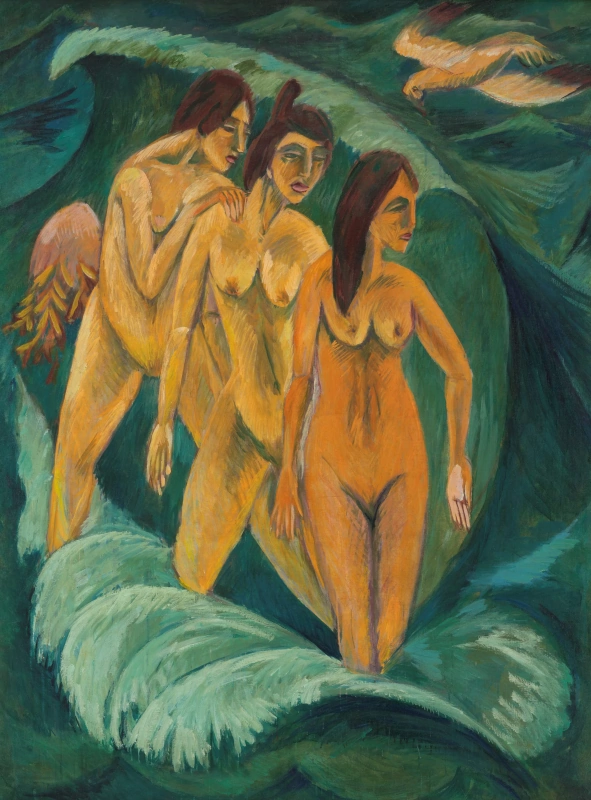

Despite the fact that there were only six Jews among the hundreds of disgraced artists, it was Jewish influence, penetrating into all spheres of art (dealers, museum directors, artists), that was associated with degeneration and decadence. Marc Chagall's paintings The Pinch of Snuff and Purim were almost a sincere acknowledgement of the artist’s own racial crime, and the satirical works of George Grosz were direct evidence of their author being a Bolshevik. But even his sincere sympathy for Hitler’s political regime did not save the artist from being labeled as "degenerate", if he supported the authorities only in words, and then came to his workshop and painted God knows what: green and blue faces, sinister masks and dancing Africans. So the exhibition in Munich displayed, for example, the paintings by Emil Nolde, who actually supported the National Socialists and sincerely believed that it was his time as that of a truly German artist.

The caricature halls of the Archaeology Institute of Munich University were visited by different people: someone laughed and spat on paintings, someone carefully studied them, probably realizing that it was the last opportunity to see contemporary art in their own country. Because nothing could stop people who four years ago burned the books of Thomas and Heinrich Mann, Erich Maria Remarque, Jack London and Ernest Hemingway in the public square in front of the Berlin Opera, from total cleansing of national museums to the sterile, ideologically safe and demonstrative brilliance.

It took Propaganda Minister Goebbels and the commission led by Ziegler almost four years to take the sensational exhibition to 12 cities in Germany. This legendary show would end only in 1941, after which some of the works would be destroyed, some — sold abroad, and very few — remain in Germany: German collectors who knew the historical price of those paintings managed to make several secret deals.

Over four years, the exhibition was visited by almost 3 million people.

It took Propaganda Minister Goebbels and the commission led by Ziegler almost four years to take the sensational exhibition to 12 cities in Germany. This legendary show would end only in 1941, after which some of the works would be destroyed, some — sold abroad, and very few — remain in Germany: German collectors who knew the historical price of those paintings managed to make several secret deals.

Over four years, the exhibition was visited by almost 3 million people.

No one was executed

"Degenerate" artists weren’t arrested. It was enough to deprive them of the opportunity to work — and everyone was free to choose the method of punishment that they could bear. Emil Nolde was forbidden to engage in any activity, professional or amateur, in the realm of art, and even to buy painting supplies. Until the end of World War II and the overthrow of the Nazis, he executed watercolours because he feared the odor of oils would compromise him. All those years, every day after finishing his work, the artist took a shovel and went to his garden to bury the paintings created during the day. Later he called this cycle Unpainted Pictures.Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, one of the founders of the artists group Die Brücke (The Bridge) committed suicide in front of his home only six months after the opening of the Degenerate Art exhibition in Munich. He had long lived in Switzerland — and could not handle the alarming news of Hitler’s possible attack on the country.

Bauhaus, the school of art, architecture and design, was closed as far back as 1933, since it was seen as a serious Bolshevik threat. Its graduates built deliberately functional buildings without signs of traditional national architecture, made sculptures from scavenged objects and argued that the subject of a painting was becoming almost irrelevant — colour itself was quite expressive. The new Germany no longer needed avant-garde

metal and plywood chairs made in the Bauhaus workshops. Let alone the obscure geometric performances, light films, photograms and dangerous abstract paintings by the school’s leading teachers. A real German chair had to be made of wood cut in a real German forest. In the same year, the former Bauhaus teacher Wassily Kandinsky left for France, and Paul Klee began teaching at the Düsseldorf Academy of Art. But it also didn’t last long. After the devastating "degenerate" exhibition in Munich, he was deprived of this position and had to return home to Switzerland.

Some artists, characters of the devastating exhibition, were no longer in the country: Oskar Kokoschka moved to Prague a year after Hitler came to power, George Grosz (whom the Nazis were especially afraid of and named "Cultural Bolshevik Number 1") was invited to America even earlier — back in 1932.

Some artists, characters of the devastating exhibition, were no longer in the country: Oskar Kokoschka moved to Prague a year after Hitler came to power, George Grosz (whom the Nazis were especially afraid of and named "Cultural Bolshevik Number 1") was invited to America even earlier — back in 1932.

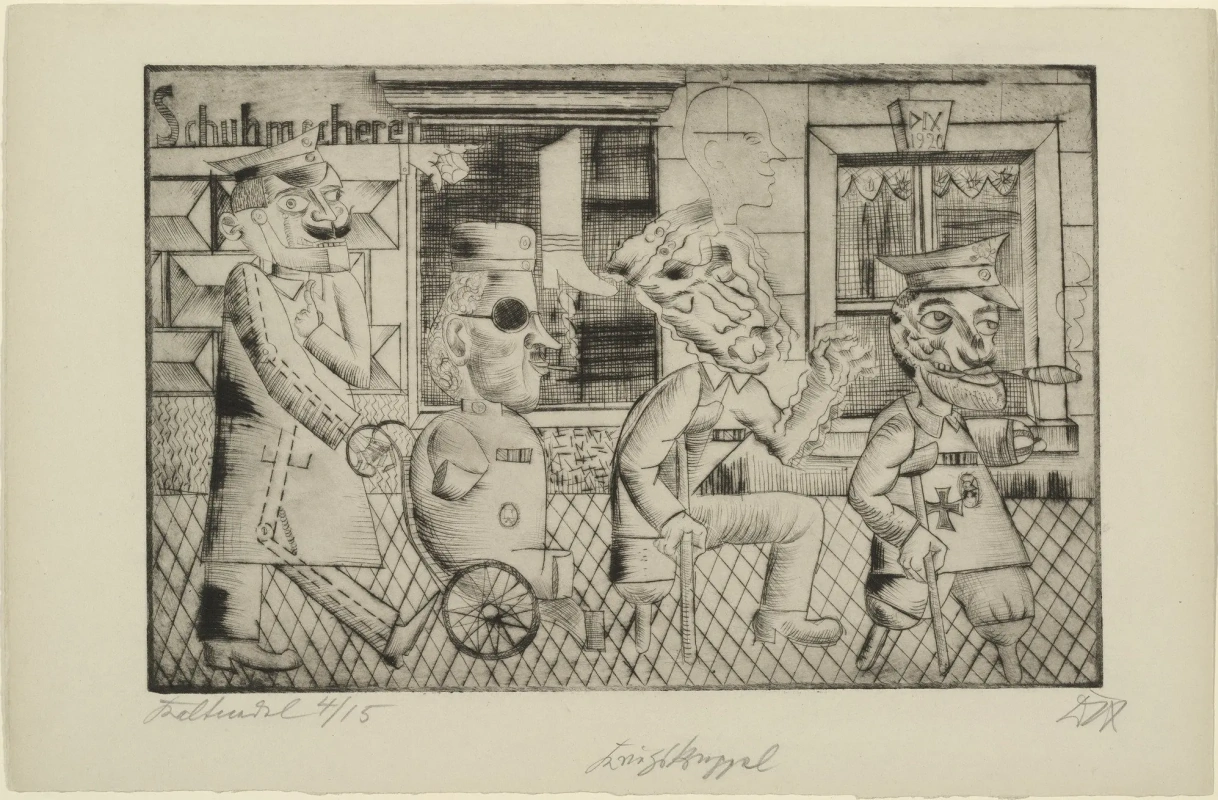

Seven Deadly Sins

1933

Otto Dix, Dadaist painter and the member of the group Neue Sachlichkeit (New Objectivity), like all other practising artists, was forced to join the Nazi government’s Reich Chamber of Fine Arts. He was sacked from his post at the Dresden Academy and ordered to paint only decorative landscapes. As if! In the midst of the reign of the National Socialists, Dix created his most ruthless satirical painting, depicting the insane dwarf Hitler, surrounded by the seven deadly sins. However, the mustache was only added to the painting in 1945. Dix was arrested on suspicion of being involved in an attempt to assassinate the Führer but was later released as there was not enough evidence to put. By the very end of the war, he was sent to the front.

Max Beckmann, who was dismissed from his teaching position at the Art School in Frankfurt, and László Moholy-Nagy left for Holland immediately after the opening of the Degenerate Art exhibition. Both of them would eventually move to America, receive well-deserved recognition and teach: the first one — in New York, and the second one — in Chicago.

Today, when modern curators are preparing retrospective exhibitions for the next tragic anniversary of the Degenerate Art exhibition, studying archival records and old photos, German museums are far behind the American ones, when it comes to the amount of collected works. In 1937, Germany almost lost its collection of contemporary art.

Max Beckmann, who was dismissed from his teaching position at the Art School in Frankfurt, and László Moholy-Nagy left for Holland immediately after the opening of the Degenerate Art exhibition. Both of them would eventually move to America, receive well-deserved recognition and teach: the first one — in New York, and the second one — in Chicago.

Today, when modern curators are preparing retrospective exhibitions for the next tragic anniversary of the Degenerate Art exhibition, studying archival records and old photos, German museums are far behind the American ones, when it comes to the amount of collected works. In 1937, Germany almost lost its collection of contemporary art.

Degenerate Art: a crib

Artists, whose works were displayed at the Degenerate Art exhibition: Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Emil Nolde, Marc Chagall, Max Beckmann, Oskar Kokoschka, Paul Klee, Wassily Kandinsky, George Grosz, Max Ernst, Lovis Corinth, Otto Dix, Lyonel Feininger, Erich Heckel, Johannes Itten, László Moholy-Nagy, Alexej von Jawlensky, El Lissitzky, Franz Marc, Piet Mondriaan, Otto Müller, Max Pechstein, Oskar Schlemmer, Karl Schmidt-Rottluff.Important paintings

Cripples of war

1920, 25.9×39.4 cm

Otto Dix survived the bloodiest battles of the First World War. Bloody trenches and emaciated prisoners of war, mutilated corpses and legless cripples, which Dix painted, harmed the reputation of a German soldier. At least Hitler thought so. The painting which was reproduced as an etching was most likely destroyed immediately after the exhibition.

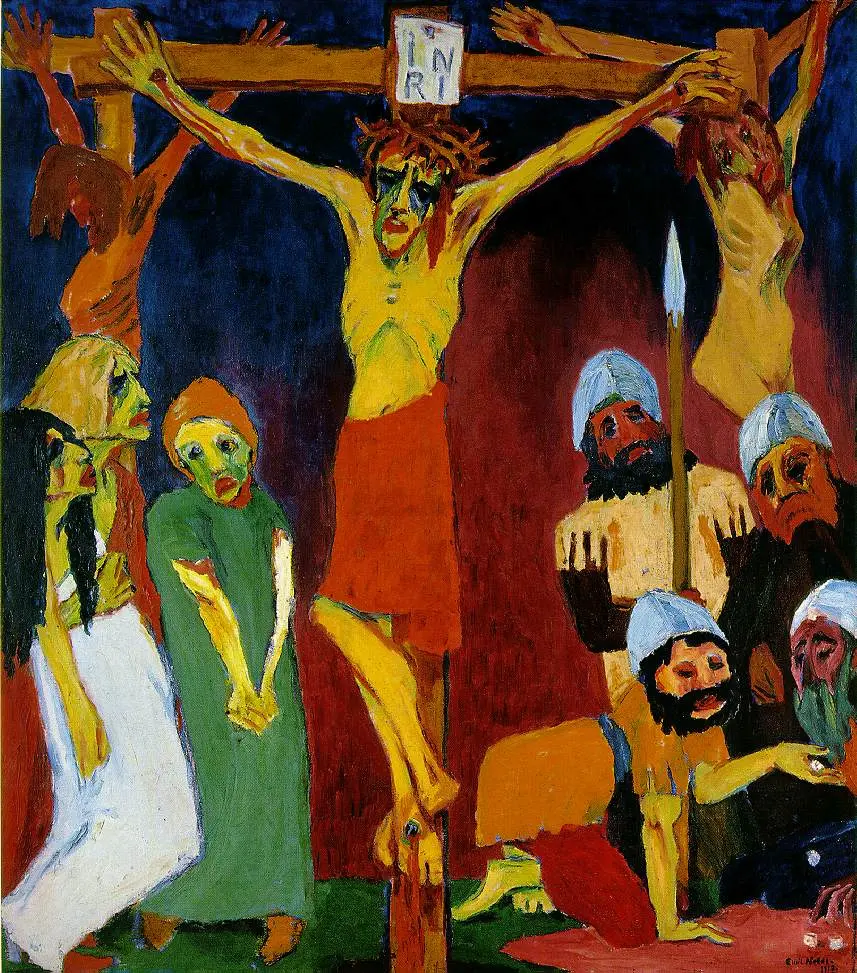

The Crucifixion of Christ

1912, 220×193 cm

The Nazis considered any images of Christ, other than the classic ones, to be offensive and caricature. Painfully yellow skin, dark circles around the eyes, distorted proportions of the face and body and figures, painted with carelessly large brush-strokes — all of this would be enough even if the character of the painting was a man of mould. But in combination with the most tragic scene from the Bible it was more like blasphemy.

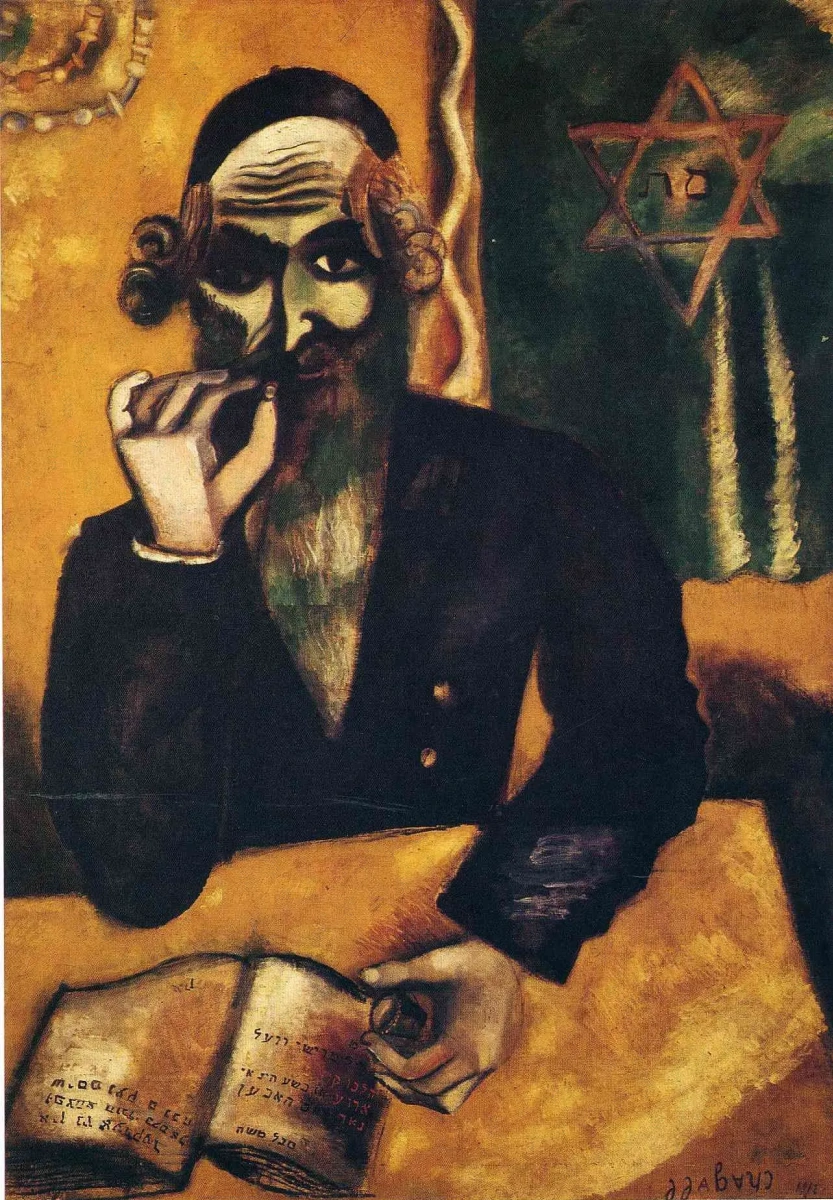

Snuff

1912, 128×90 cm

Mark Chagall just had to paint anything to get on the list of degenerate artists. He was a Jewish artist, whose 200 paintings were in German museums by the early 1930s. So painting a portrait of a Jew with the Star of David, blatantly glowing behind his back, was considered by the Nazis a recognition of his own racial and artistic inferiority.

Departure

1935, 215.3×314.6 cm

Beckmann’s giant (2×3 metres) triptych resembles the form traditionally used in the design of the altar part of the cathedrals. This makes the bizarrely merging figures in the left and right parts of the painting look even more disturbing. Beckmann never stated that his painting had any political sense, but later it became unequivocally interpreted as the artist’s premonition of his inevitable emigration.

You are a layman if you:

— just like Hitler, call the artists "degenerate" because their paintings have no subject, faces in them are green or the grass is red.

— are ready to personally remove from the walls of museums a couple of masterpieces, cover up David’s genitalia with a cap or in any other way fight against the "offensive" art.

You are an expert if you:

— use the word "degenerate" while describing an artist only in the context of his participation in the famous exhibition,

— hope that the lost Tower of Blue Horses by Franz Marc and War Cripples by George Grosz will miraculously be found in one of the secret apartments of some former functionary of Nazi Germany.

Author: Anna Sidelnikova

Cover illustration: the detail of The Seven Deadly Sins by Otto Dix.

Cover illustration: the detail of The Seven Deadly Sins by Otto Dix.

Arthive: follow us on Instagram

Los pintores mencionados en el artículo