On the Internet, one can often come across a comparison of Pablo Picasso’s works from different periods of creative activity, followed by comments about degradation, and stating that he "forgot how to paint" or simply scoffed at his audience, forcing them to buy daubry signed by his name. Of course, the artist had quite a sense of humor, but can we really call him nothing but a skillfully advertised attention seeker? Or is it actually more complicated than that? Well, let’s get this sorted out.

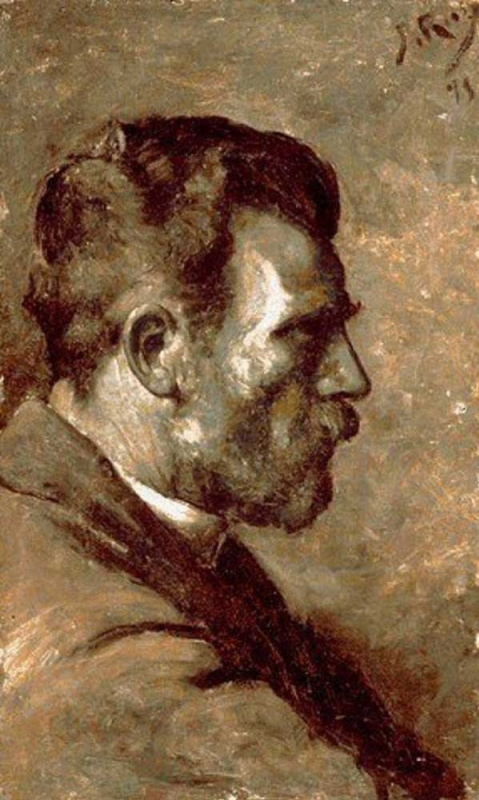

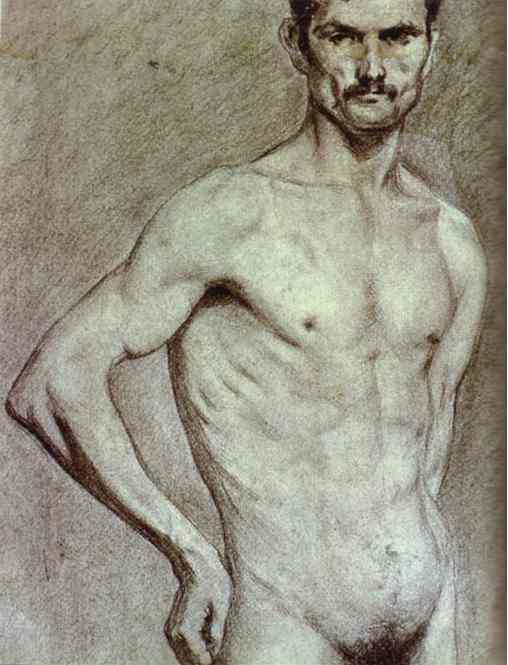

Picasso definitely knew how to paint. And he did it well

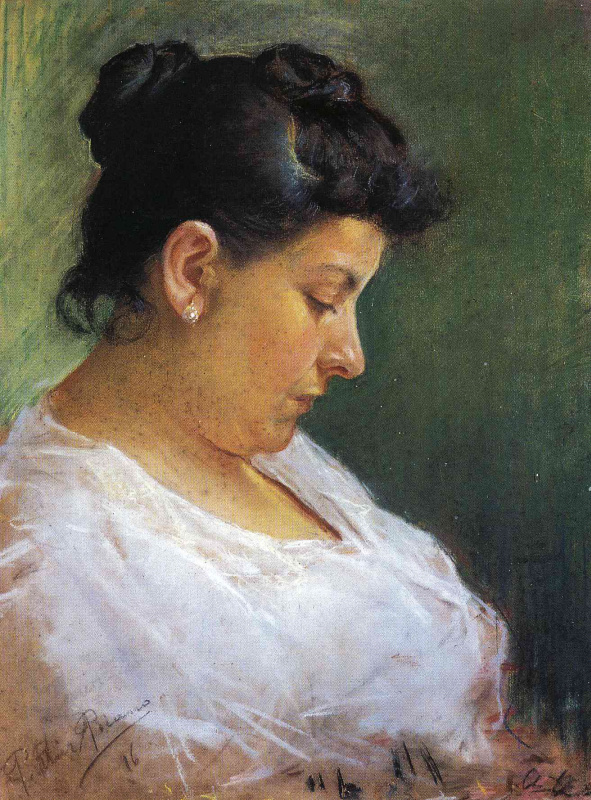

They say, in order to defeat your enemy, you have to understand them. Picasso managed to defend his work so successfully and achieved such fame, among other things, because at first he was "on the other side". He created pictures from the moment he learned to hold a pencil until his death. And he received the most traditional academic art education: at first, from his father, and then in several art schools and at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Madrid.Thanks to his classical education, Picasso mastered the whole range of techniques available at that time — from etching to sculpture. And while creating his "non-traditional" works, the artist did not abandon the familiar, time-tested tools. He just figured out how to use them in new ways. Picasso destroyed the usual methods, literally took them apart piece by piece. But unlike many rebels who existed at all times, he destroyed not for the sake of destruction, but in order to build something new from the "building materials" he got.

This is, perhaps, what true mastery is: taking all the best from the great predecessors, studying the composition, shape and color, getting the hang of the basic techniques and learning the rules just to understand how to break them. Not letting the influence of other masters hold you back. If Picasso had decided to keep to the beaten track, he would certainly have achieved considerable success. He was a great drawing artist and a very talented imitator. This is evident by one impressive story.

When Henri Matisse was at the height of his fame with his series of odalisques, Picasso, as a joke, painted an odalisque at the telephone, and for this incongruity perfectly imitated Matisse’s brush strokes, style, and colors, and his background of Orientalism — everything, including his signature. The joke was so convincing that one of the most serious of the Paris art magazines, on getting hold of a photograph of the telephoning odalisque, solemnly reproduced it as a genuine Matisse.

When Henri Matisse was at the height of his fame with his series of odalisques, Picasso, as a joke, painted an odalisque at the telephone, and for this incongruity perfectly imitated Matisse’s brush strokes, style, and colors, and his background of Orientalism — everything, including his signature. The joke was so convincing that one of the most serious of the Paris art magazines, on getting hold of a photograph of the telephoning odalisque, solemnly reproduced it as a genuine Matisse.

"Great artists are just like great inventors or discoverers: after their discovery, it is difficult to continue living as we used to. They change the world and change the view of a person or even of the whole mankind on this world."

Read also: 10 questions kids ask about art

Read also: 10 questions kids ask about art

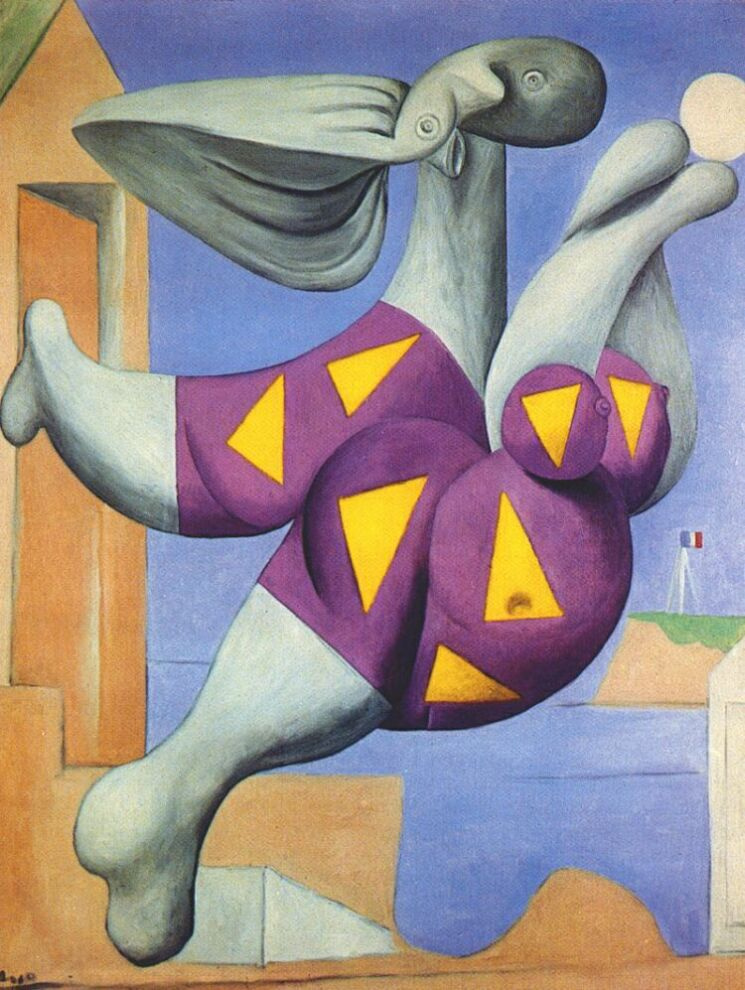

Picasso was never ashamed of "regressing to his childhood"

In fact, many great painters loved to joke and fool around. Quite the contrary — there are not so many artists who become dead serious when it comes to their work.

Pablo Picasso poses as Popeye. Photo: André Villers, 1957.

Picasso often said that he admired primitive art and drawings made by children. Once he said: "When I was their age I could draw like Raphael, but it took me a lifetime to learn to draw like them." And there is something in it. Most artists know that it is almost impossible for a person who already knows all the drawing rules to accurately imitate a picture drawn by a child. Children have no fear of an empty canvas, are not constrained by any set limits, and don’t have several generations of ghostly painters watching them from behind and making sure that everything is done according to the canons. Only children fully possess the omnipotence of the beginner, who does not yet know "how it should be done." This is precisely what Picasso’s aim was: finding out how to forget everything that has already been studied and is familiar in order to be able and allow himself to draw with a child-like frankness and honesty.

Bather with beach ball

1932, 156.2×114.6 cm

Moreover, Picasso never took himself too seriously. He did not allow himself to "succumb to stardom" and turn into a venerable master, who constantly utters words of wisdom. He liked masks and playing dress-up, often received guests while wearing unusual outfits, enjoyed taking pictures of himself taking a bath or dancing in front of his paintings, wearing night-clothes. At the premiere of the film The Mystery of Picasso at the Cannes Film Festival, the artist, who was usually seen in shorts, sandals and a vest, suddenly appeared wearing a formal suit and a bowler hat. Perhaps it was this ability to preserve children’s perception that Picasso’s success as an artist depended on (at least to some extent).

Picasso never stopped seeking for inspiration

At least one thing in Picasso really fell under the conventional image of an artist: there was always a terrible mess in each of his studios. It was part of the creative process. The artist was surrounded by African sculptures, bronze statues, ceramics, musical instruments with torn strings and, of course, paintings — his own ones and those created by others. The artist’s friends said that he didn’t throw anything away, keeping bills, bottle labels and even broken things. Despite his fame and fortune, Picasso was quite modest in everyday matters and very stingy. Probably, it was due to the impoverished Parisian youth that Pablo spent in the windswept "Washhouse Boat" ("Bateau-Lavoir"), where he had to live in a tiny dirty room and earn money for food and paint by hook or by crook.Once Picasso was asked about the choice of colors for his paintings of the blue period. He replied that he simply had no other paints. Of course, now it is impossible to determine whether the artist spoke the truth or was just joking around. Nevertheless, the ability to create something, using a very limited set of materials is a valuable skill. Still, Picasso was never short of themes. He constantly absorbed everything that could be "remelted" into an art piece: ideas and conversations, spied scenes and interesting types, emotions and fantasies.

Picasso worked very quickly. Usually, it took him a brief glimpse of an idea to paint a picture. But sometimes, especially when it came to very important for him canvases, the work could take up to several months. It happened to Guernica and Les Demoiselles d’Avignon. It seems fair to say that it was Henri Matisse and his Joy of Life (1906) that inspired Picasso to paint Les Demoiselles d’Avignon. Matisse’s work was an overwhelming success, and Picasso began thinking what he could set against such a masterpiece. He wanted to create something as impressive as that painting, but at the same time something unique. In an attempt to take a new look at Western painting methods, Picasso filled several drawing-books with sketches. He decided to turn to the very beginnings, i.e. primitive art. African sculptures and works by Native Americans, which he saw in the Museum of Ethnography in Paris, impressed him with a completely different approach to form. Those were not the attempts to recreate the world around us, but rather the symbolic, almost shamanistic view of it.

Les demoiselles d'Avignon

1907, 243.9×233.7 cm

After eight long months of work, Picasso managed to complete his "counter-masterpiece" - a frightening, daring painting Les Demoiselles D’Avignon which striked the viewers with its angular irregular shapes. At that time, the canvas was way too provocative. Picasso showed it to only a few friends, and it shocked them so much that the artist hid it from prying eyes. Les Demoiselles D’Avignon was first presented to the public almost 10 years after its creation. During that time, a real revolution had happened in painting. The revolution, which became possible largely due to this "counter-masterpiece."

Picasso wasn't an exceptionally good person, but it also became part of his work

Now, in the era of the #MeToo movement and the third wave of feminism, the way Picasso treated women is often brought up. It has been suggested that the artist had a narcissistic personality disorder, because of which he would become almost obsessed with a woman, idealize her (perhaps even believe that every new woman was the love of his life), but then become disappointed rather quickly and turn her life into a nightmare. Basically, there is nothing to argue about here: Picasso psychologically traumatized almost all of his beloveds with only a few happy exceptions. He himself said that every time he started a relationship with a new woman, he destroyed her predecessor. However, in spite of the fact that this attitude towards people cannot by any means be justified, we aren’t the ones to make diagnoses. But here what journalist and art historian Miles Unger, author of the book Picasso and the Painting That Shocked the World, says about it:"Picasso came from a patriarchal family and part of the world in which women were expected to stay at home and take care of their husbands and children. Your social life revolved around men. Men were your intellectual and drinking companions. For sex, you went to the whorehouse, and occasionally came home to your wife. So, as a lover and husband, I think he was horrible.

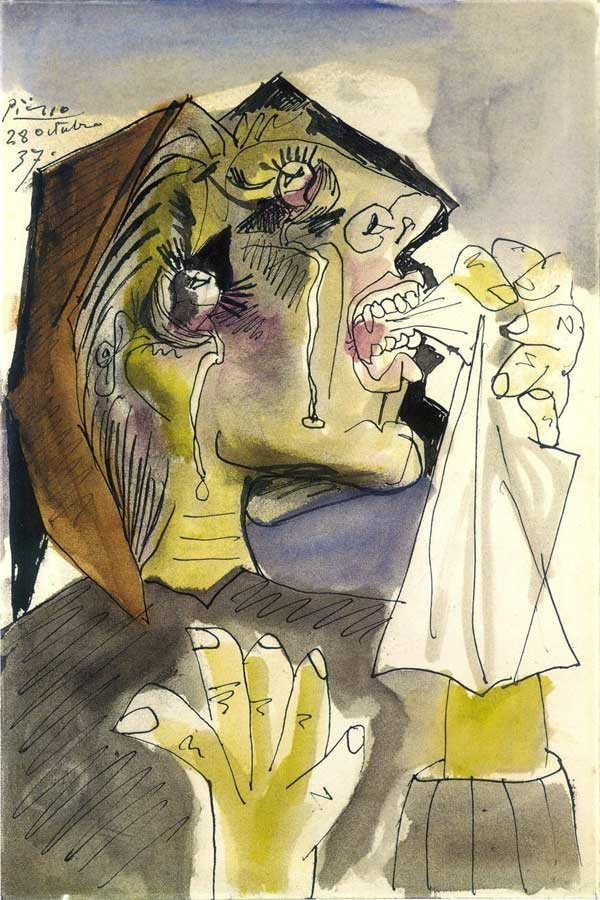

Weeping woman with handkerchief. Dora Maar

1937, 40×26 cm

Some people, when confronted with an artist like Picasso, say he was a great artist but a terrible human being, but that the two have nothing to do with each other. I think that’s a mistake, particularly in the case of Picasso, because his attitudes toward women were so much a part of his art. If you look at Les Demoiselles D’Avignon, the fury and conflicted feelings about women all come through. That doesn’t mean we should forgive his treatment of real women. But one should also recognize that art can often come from a very dark and furious place, just as Matisse’s art came from a joyful, sensual, much-less-conflicted place."

Picasso knew how to sell himself, but despised fame

Pablo Picasso once said: "Artist is a person who paints what you can sell. A good artist is a person who sells what he paints." Yet, there’s one thing that can be said for this scandalous Spaniard — he always stayed true to himself. It took Picasso quite some time to become famous and marketable. He tried to "conquer Paris" several times: he failed, became disappointed, gave up, left, but then made a new attempt. Right, the artist was favored by Ambroise Vollard, and over time, gained influential patrons, Gertrude and Leo Stein, but for the most part, Picasso had to make his own way in the world. Yet, he never tried to become someone the public wanted him to be and to create "pretty" paintings. And when Picasso finally achieved popularity, he was not afraid to continue his creative search and experiments.Picasso radically changed the style of his work several times during his long creative career. Perhaps this also became part of his secret of "eternal youth." This is what the philosopher Lev Shestov said about the artist’s acquisition of a recognizable manner: "Every art lover is happy to recognize the "manner" of the artist in a new work, but very few people realize that the acquisition of that manner marks the beginning of the end. Artists understand this well and would gladly get rid of their manner, which they already consider a template. But this requires too much effort, new hardships, doubts, and uncertainty — those who once experienced "the delights of creativity", would never be tempted by them again. They prefer to "work" under the template created before, just to be calm and absolutely confident in the results — they are lucky enough to be the only ones who know that they are no longer creators."

However, despite the fact that Picasso did all his best to become popular, his attitude towards his own fame was quite contradictory. Miles Unger said that the artist hated the sycophants and hypocrites who came to him as if on pilgrimage to "kiss the ring of the genius." Anyone who called Picasso a Master was shouted at and kicked out; once the artist was so fed up with streams of flattering speeches that he drew his revolver and fired a round into the air. He appreciated conversations about art and his paintings, but couldn’t stand thoughtless and blind reverence.

However, despite the fact that Picasso did all his best to become popular, his attitude towards his own fame was quite contradictory. Miles Unger said that the artist hated the sycophants and hypocrites who came to him as if on pilgrimage to "kiss the ring of the genius." Anyone who called Picasso a Master was shouted at and kicked out; once the artist was so fed up with streams of flattering speeches that he drew his revolver and fired a round into the air. He appreciated conversations about art and his paintings, but couldn’t stand thoughtless and blind reverence.

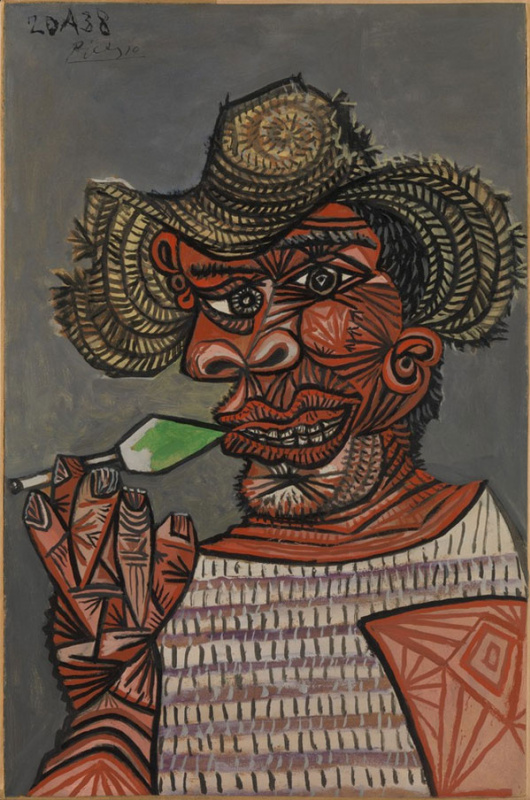

Pablo Picasso wearing a cowboy hat and holding a revolver given to him by Gary Cooper. Photo: René Burri, 1957

Picasso was ruthless with himself

In 1952, being interviewed by the writer Giovanni Papini, Picasso said: "Today, as you know, I am famous, I am rich. But when I am alone with myself, I haven’t the courage to consider myself an artist in the ancient sense of the word. Great painters are people like Giotto, Titian, Rembrandt, Goya. I am only a public entertainer who has understood the times and has exploited as best he could the imbecility, the vanity and the greed of his contemporaries. Mine is a bitter confession, more painful than might seem, but it has the merit of being sincere."

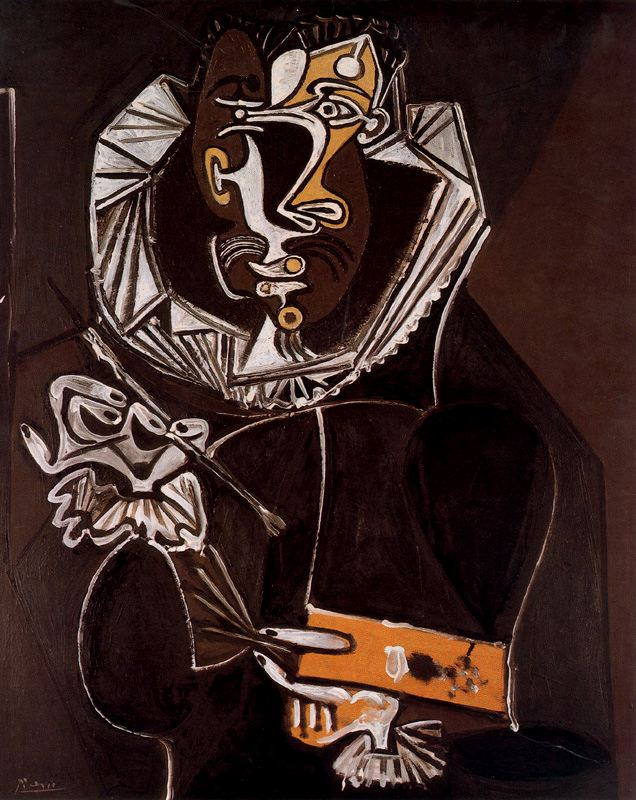

Sitting man

1970, 145.5×114 cm

Art critic Jonathan Jones wrote in The Guardian about every single work by Picasso being an illustration of some specific episode of his biography. Sometimes it is quite obvious, like portraits of wives, mistresses and friends. Sometimes it is encrypted or symbolic. His art has always been self-exposing, and often even self-recriminating. Picasso never gave himself too much credit or tried to show himself in the best light possible. His whole life is spread out before the viewer — passions and fears, love and hate, admiration and envy. Perhaps, the artist’s latest works are particularly illustrative in this respect. In the last years of his life, he often painted himself: not the venerable gray-haired thinker, but a short grotesque old man, dressed in the costume of a musketeer and comically trying to play the familiar role of the ladies' man.