The Seattle Art Museum celebrates the 100th anniversary of the birth of one of the most famous American artists of the 20th century. The exhibition "Andrew Wyeth: In Retrospect" is the largest examination of the artist’s work in the eight years that have passed since his death. The exposition of the 110 best paintings and drawings by Wyeth defies the traditional idea of him as a realist and offers an unexpected look at his art, heritage and influence.

The curators covered the period from the late 1930's to 2008 and included several rarely seen loans from the Wyeth family collection.

Winter fields

1942, 44×104.1 cm

Andrew Wyeth (1917 — 2009) received the only artistic training in the studio of his father, Newell Convers Wyeth, a famous illustrator. His apprenticeship begins at the age of fifteen, and by the time he is 20 the young artist sells out his first New York exhibition of watercolors. Four years later, he exhibited the works that began to define his signature style: highly detailed, strangely hyper-realistic paintings in egg tempera. These large temperas were shown for the first time at the Museum of Modern Art in 1943. From that time, Andrew Wyeth began to emerge from the shadow of his father’s art fame.

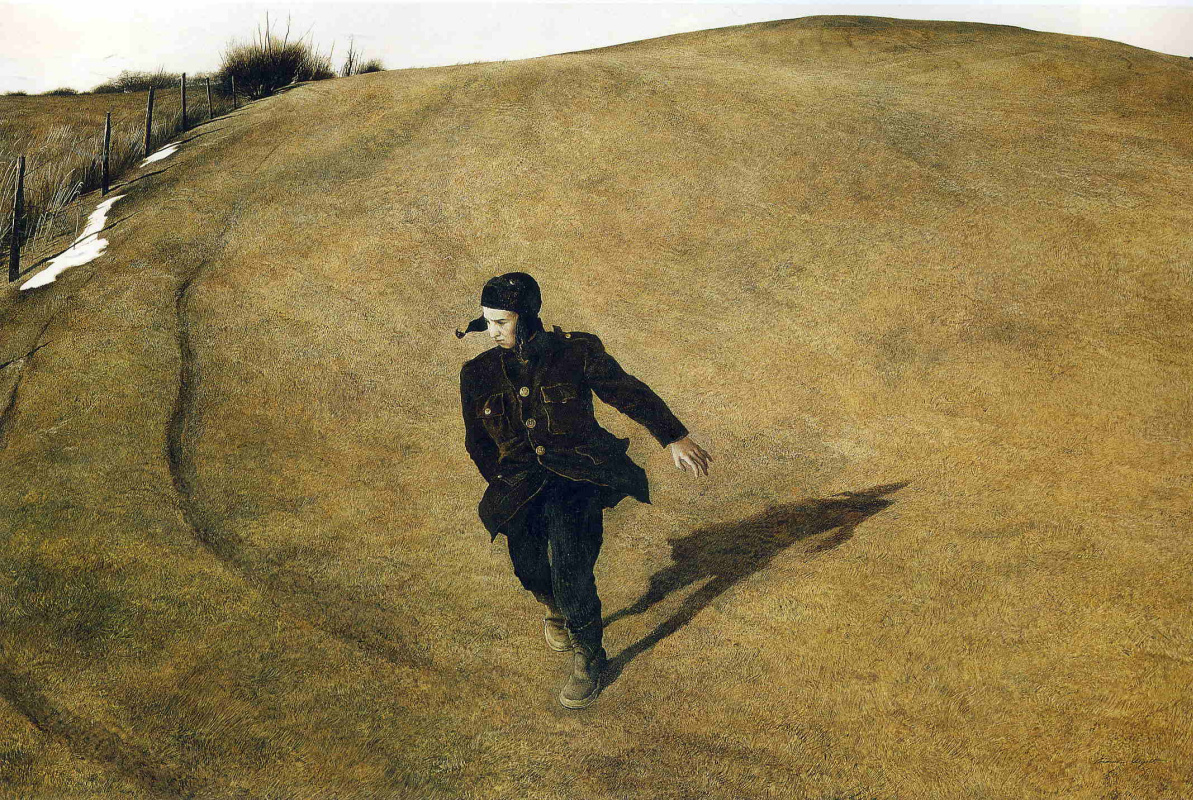

Winter 1946

1946, 79.7×121.9 cm

Andrew Wyeth, "Christina Olson" (1947). Curtis Gallery, Minneapolis

The Seattle "In Retrospective" opens with a gallery of significant works introducing the cast of subjects from Wyeth’s world featured in some of his most famous portraits, such as Christina Olson of Maine and Karl Kuerner, his neighbour in Chadds Ford, Pennsylvania. In 1947, Andrew Wyeth completed his first portrait of Christina Olson, who suffered from a degenerative muscle disorder that left her unable to walk,. A year later, the New York Museum of Modern Art acquired his next painting of her, Christina’s World (see the cover illustration to the article). Olson became Wyeth’s friend and muse. He painted Christina and her house in Maine every summer until she died in January 1968, at age of 74.

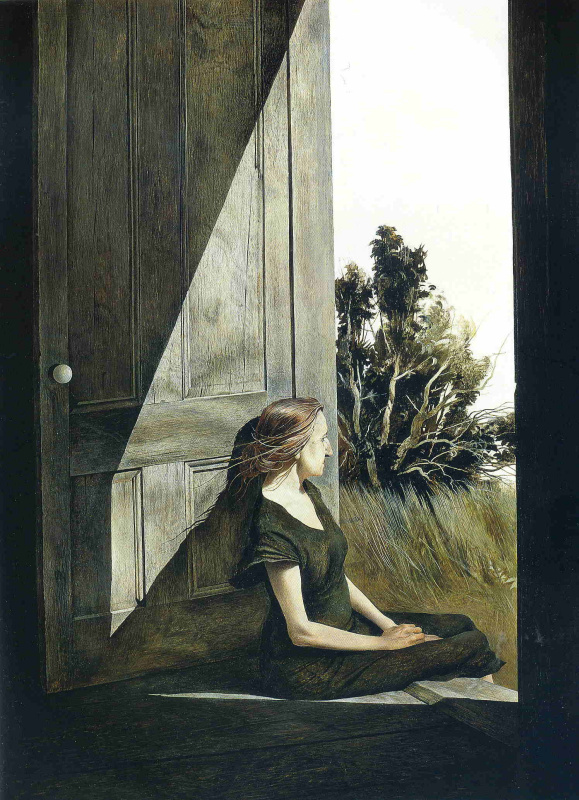

The day of Pentecost

1989

"His portraits, figures, and landscapes reveal a complex mind investigating the deepest human emotions: love, death, and how we experience the passing of time," said Patricia Junker, a curator.

In 1948, Wyeth painted his first portrait of Karl, a machine gunner in the German army in World War I. The artist executed numerous paintings of his neighbour, his wife Anna and their possessions. Over the years, Wyeth imbued the details with layered meaning as he contemplated mortality, and love of Karl, and the withdrawn depression of Anna, who refused to sit for him. Theirs was a life of survival on the farm where death was often nonchalant and love was tenuous.

The Kuerners

1971, 67×102 cm

After the first gallery, the exhibition is organized in rough chronological order, tracing Wyeth’s development from his earliest watercolors, to more staged works of the 1940s-50s, and to deeper technical experimentation in the 1950s-60s, incorporating elements of chance.

Braids (from the series "Helga")

1979, 41.9×52.1 cm

In the 1970s, Andrew Wyeth became enchanted by Helga Testorf, who began to work for the aging Kuerners as household help. In the attic of the Kuerner home he painted Helga, a married woman, in secret from his wife, Betsy — a secret he kept for almost fifteen years. Wyeth hid these studies of nude Helga at the neighbours'; he also painted Helga in his sister Carolyn’s painting studio, adjacent to their father’s old studio. The secret life added to the psychological tension of all Wyeth’s paintings in these, the Helga years.

Also from this era are complex, more abstract paintings that stand out against the rest of Wyeth’s oeuvre, including Thin Ice (1969), an early work on loan from a private collection in Japan being shown for the first time on the West Coast.

Also from this era are complex, more abstract paintings that stand out against the rest of Wyeth’s oeuvre, including Thin Ice (1969), an early work on loan from a private collection in Japan being shown for the first time on the West Coast.

Thin ice

1969

"I am an illustrator of my own life," Wyeth said. Andrew Wyeth painted his Chadds Ford characters, living and dead, into "Self-Portrait: Snow Hill". He began to work on it in 1987, the year of his 70th birthday. Betsy Wyeth likened her husband to Swedish director, Ingmar Bergman, "He’s creating a world they [his models] don’t realize and they’re acting out a part without any script." His models dance on Kuerner’s Hill and recall Bergman’s dance of death from the iconic final scene of The Seventh Seal. These characters never again appeared in his paintings. Wyeth infused an increasingly mystical quality into his painting symbolism

from that point forward. He continued to paint until his death in 2009, at age of 91.

Self-portrait: snow hill

1989, 83.8×116.8 cm

"Andrew Wyeth: In Retrospect" is on view at the Seattle Art Museum till January 15, 2018.

Visitor at the exhibition "Andrew Wyeth. In retrospect" examines the picture "Airborne" (1996). Photo: Stephanie Fink via Artnet.com

Follow ArtHive on Instagram

Adapted from the official website of the Art Museum of Seattle and Artdaily.com