It was the same disaster that once demolished Pompeii that made that provincial locality an international brand. The only city that has come to us fully preserved from ancient times, it is still full of surprises, as, now and then, superb frescoes show themselves again after two thousand years' long oblivion. Their brilliant artfulness continues to puzzle researchers, while sceptics deny their authenticity and long age. And Pompeii keeps surprising us again and again…

Pompeian paintings are the city’s most singular feature. Still, when speaking of Pompeii, we ought not to forget Herculaneum and Stabiae, Oplontis and Boscoreale — all the towns that, along with Pompeii, suffered from the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in AD 79. In each of them, beautiful frescoes were discovered, that are of both aesthetic value and scientific interest.

The fact is that Greece was in favour with the Pompeiians, who practised Greek art and even Greek religion. Classical Greek antiquities that have survived in the original are less than scarce, and it is especially so when it comes to painting. To some extent, the murals of Pompeii and Herculaneum perfectly preserved under the layer of volcanic ash can make for the loss. A number of them are copies of lost Greek originals.

The fact is that Greece was in favour with the Pompeiians, who practised Greek art and even Greek religion. Classical Greek antiquities that have survived in the original are less than scarce, and it is especially so when it comes to painting. To some extent, the murals of Pompeii and Herculaneum perfectly preserved under the layer of volcanic ash can make for the loss. A number of them are copies of lost Greek originals.

Cultural province

The city now known as Pompeii, in ancient times, had an impressive official name Colonia Cornelia Veneria Pompeianorum. It was named so by Lucius Cornelius Sulla — he founded a Roman colony in Pompeii, and thus, made the Pompeiians Roman citizens.Model of Pompeii. National Archaeological Museum of Naples (photo)

As time went by, the colony, small at first, by the 1st century BC, developed into a well-organised cultural centre. Private houses and public buildings were constructed, streets paved, an amphitheatre appeared. All these were profusely decorated with frescoes, mosaics, sculptures.

By imperial standards, Pompeii was but a provincial backwater. Still more surprising, then, is the popularity of art there — so masterly, expressive, and original art that it is often equalled to that of the Renaissance . However, its creators were not the best artists of those days (the best must have been in Rome) — just skilful craftsmen.

By imperial standards, Pompeii was but a provincial backwater. Still more surprising, then, is the popularity of art there — so masterly, expressive, and original art that it is often equalled to that of the Renaissance . However, its creators were not the best artists of those days (the best must have been in Rome) — just skilful craftsmen.

Ancient portraiture

It may seem surprising that the artists of those distant centuries were familiar with practically all genres of painting: historical and mythological pictures, domestic and allegorical scenes, portraits, landscapes, and still lifes.The most famous of Pompeiian frescoes is, perhaps, the round medallion Woman with wax tablets and stylus (so-called Sappho).

Portrait of a young girl (Portrait of the poetess Sappho?)

I century, 37×38 cm

It was discovered in June, 1760. For a long time, it was believed to be a likeness of the celebrated poetess Sappho, who, in the classical world, was an ideal of beauty and harmony. In fact, it is a typical picture of a well-educated young noblewoman, ranking high in society (as indicated by the golden decorations she is wearing). Medallions like this were supposed to praise a woman’s high morals and bodily perfection, so they can hardly be qualified as lifelike.

In Pompeii, there occur companion portraits of married couples. It may seem strange that in these portraits, the wife is often portrayed holding a stylus and a wax tablet. A whole city inhabited by women writers — can it be so? Actually, not. These attributes are by no means indicative of the wife’s gift for belles-lettres — only of her proficiency at housekeeping. For girls of good family, learning to write and count was a must, as they were supposed to manage a household and calculate the expenses. So, the tablet and the stylus in the portrait are rather a reference to household economy.

The design of Pompeiian dwellings

The Pompeiians had a taste for decorating their homes, and the art of mural painting there never stopped developing. When referring to it, four styles, or systems of decorating houses, are usually mentioned. They were originally delineated and described by the German archaeologist and art historian August Mau. After moving from Germany to Italy in 1872, the researcher spent the next 25 years studying Pompeiian murals. His research work, including the idea of the Pompeiian styles, resulted in a few books and a lot of articles.The First style, referred to as incrustation style (2nd cent. BC — 1st cent. BC), is simple and austere. The walls were lined with rusticated stone (that is, with the face of each block deliberately remaining unworked, rough in appearance). Often, the blocks were decorated with moulding, or painted in imitation of marble. It was not fresco painting in the proper sense of the word, but, rather, revealing the wall’s structural features. This design looked so elegant and sublime that some villa owners would not change it to comply with the latest stylistic trends.

Ancient frescoes are frequently compared to those of later periods (Classicism , Romanticism). But sometimes, the First style can, quite unexpectedly, be reminiscent of Mark Rothko (see the photo below).

The term for the Second style is architectural (80 BC — 30 AD). Paintings of that period became dynamic, and the architecture, richer than before, was now only shown by means of murals. The scenery of the interiors became more and more complex, with new details and elements. Landscapes began to appear on the walls, and finally, human figures were introduced in the compositions. As early as then, painters strove to render the perspective of houses and streets, to give the impression of visual depth.

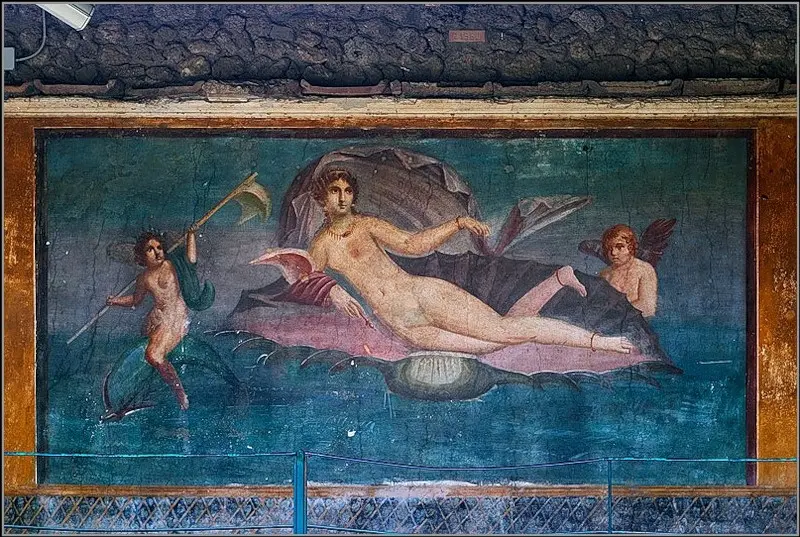

No wonder that in this style, the effect of optical illusion known as trompe-l'œil became common practice. Normally, Romans placed trompe-l'œil compositions in spacious indoor areas, like front rooms or peristyles (an open space within the house, a courtyard or garden, surrounded by a roofed portico). The artist’s imagination could make the landscape

an optical expansion of the garden (see the photo below), or show it as if viewed from a window painted on the wall.

A trompe-l'œil. House of Venus in the Shell, Pompeii

The best-known frescoes of that period are the series of murals found at the Villa of the Mysteries. The place includes sixty luxurious, well-preserved rooms, of which the most notable is the ‘Hall of Dionysian Mysteries' (see the photo below) painted with vermillion.

‘Hall of Dionysian Mysteries.' Villa of the Mysteries, Pompeii

The bright red colour often termed ‘Pompeiian red' gained great popularity in Europe after the rediscovery of Pompeii and became fashionable and widely used in the interiors of the Old World.

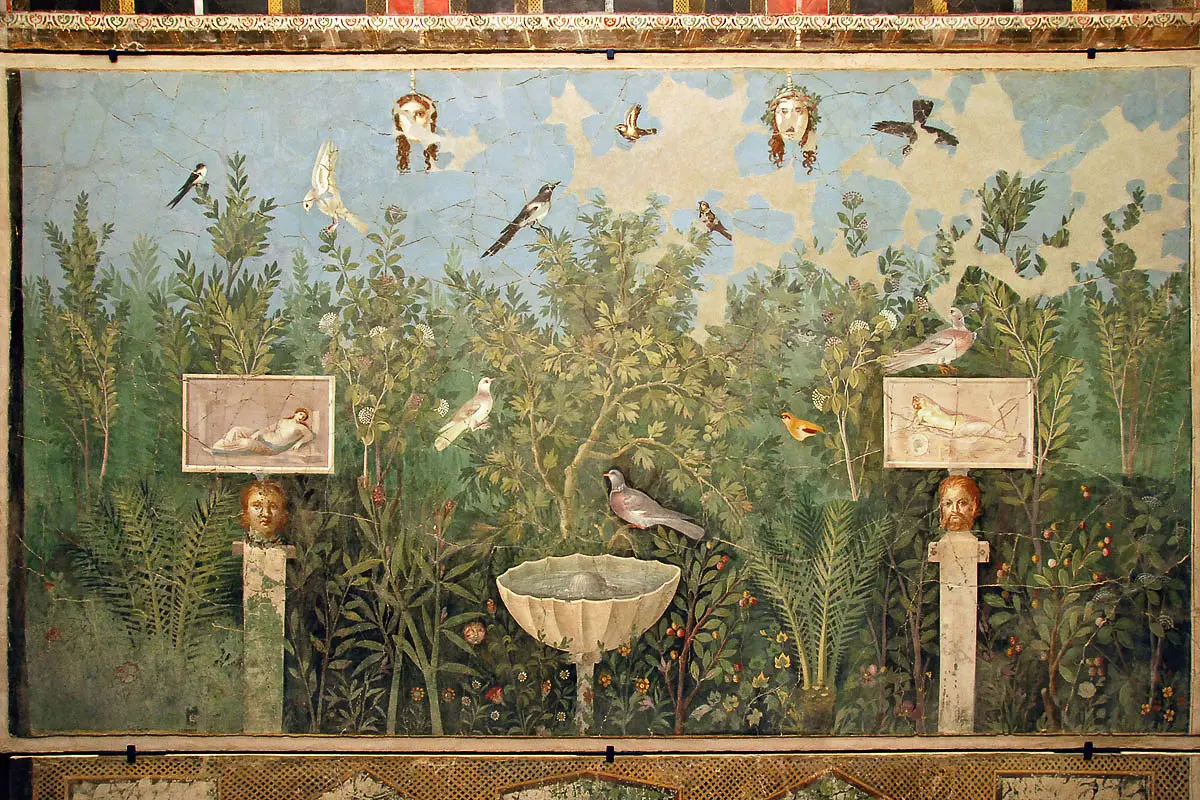

The Third style, or ornate style (the first half of the 1st cent. AD), is no longer characterised by the use of perspective, but is more light and airy. Typical are delicate structures like candelabra. Architectural details are less important, and long bands hanging around them start to be commonly used instead as a decorative element. Occasionally, the composition is complimented with a small scene in the centre of the wall — no longer eye-catching, but rather contemplative (see photo 1, photo 2 below)

Examples of the Third style (according to Mau). A beautiful garden scene decorating a room of the ‘House of the Golden Bracelet (see photos 1 and 2 below)

After the Roman Empire

incorporated Egypt, new motifs enriched Pompeiian painting: pictures of Egyptian gods, sphinxes, herons, and lotus flowers appeared on the walls.

In 62 AD, an earthquake shook the city as if to warn the people to be alert. Though it caused much damage, the Pompeiians did not get into a panic, but vigorously devoted themselves to creative work. They viewed the earthquake as a good reason to redecorate their residences in compliance with the latest trends. For the last seventeen years of Pompeii’s existence, the city experienced a building boom. Old houses were being restored, new ones started. Pitifully, the people’s magnificent projects of the renewal of their city and houses did not take into account the volcano called Mount Vesuvius.

To be fair, only few people knew that Mount Vesuvius was a dormant volcano, and to earth shocks the citizens had long been accustomed.

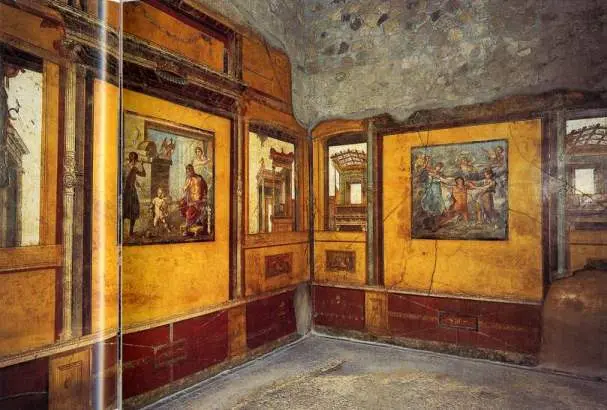

The Fourth style (called intricate) became popular following the earthquake (63 AD — early 2nd cent. AD). It featured no new elements, but was a combination of what had been achieved in the three previous styles. However, it is easily recognisable by its fantastic themes, dynamism, and multi-figured compositions. Typical mythological scenes in the frescoes were shown against the background of dream-like constructions and landscapes looking like stage setting.

To be fair, only few people knew that Mount Vesuvius was a dormant volcano, and to earth shocks the citizens had long been accustomed.

The Fourth style (called intricate) became popular following the earthquake (63 AD — early 2nd cent. AD). It featured no new elements, but was a combination of what had been achieved in the three previous styles. However, it is easily recognisable by its fantastic themes, dynamism, and multi-figured compositions. Typical mythological scenes in the frescoes were shown against the background of dream-like constructions and landscapes looking like stage setting.

Cupids acting as goldsmiths. Fresco from the dinner hall of the 'House of the Vettii,' Pompeii, 60—79 AD (photo)

Still lifes, generally not very popular, were quite frequent in that period. Though they were normally placed at the top of the wall rather than in the centre, they presented great meticulousness in execution. That is why the still lifes are so valuable as a source of information about the Roman way of life. For example, especially noticeable is the preference of glassware to pottery.

‘Accessible to people of mature age and respected morals’

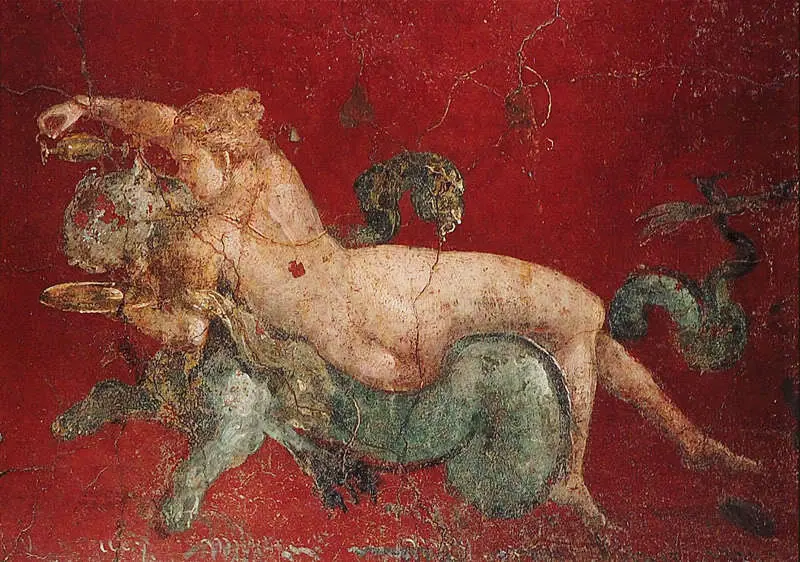

Pompeii are also known for their erotic frescoes. In the course of excavations, they were discovered on the walls of a lupanar (a brothel) that would later become an object of extremely high interest for tourists. In ancient times, as archaeologists say, it was frequented by wealthy merchants and politicians.

In places like this, frescoes were a sort of menu of sexual services performed by the girls (mainly slaves from Greece and Oriental countries).

Even if a customer did not speak the language, he could just stab his finger at the picture he had chosen (photo).

But erotica was also an element of the citizens' everyday life. Frivolous frescoes decorated not only brothels, but the walls of public facilities, rich villas, and ordinary dwellings.

The sexual artworks excavated in Pompeii were, for a long time, considered ‘inappropriate' for public view. The objects were transferred to the National Archaeological Museum of Naples without an idea what should be done with them. Finally, in 1819, King Francis I, who visited the museum with his wife and daughter, ordered to shut away all the ‘obscene' pieces of art in a single room — the so-called Secret Cabinet.

Years later, the admission to the Cabinet was only opened ‘to people of mature age and respected morals.' Starting from the 1960s, the restrictions have been little by little removed, and now the Cabinet is accessible for adult visitors.

Nowadays, these frescoes are property of the state, and the Pompeiian lupanar is a protected World Heritage Site — strange, but true.

The sexual artworks excavated in Pompeii were, for a long time, considered ‘inappropriate' for public view. The objects were transferred to the National Archaeological Museum of Naples without an idea what should be done with them. Finally, in 1819, King Francis I, who visited the museum with his wife and daughter, ordered to shut away all the ‘obscene' pieces of art in a single room — the so-called Secret Cabinet.

Years later, the admission to the Cabinet was only opened ‘to people of mature age and respected morals.' Starting from the 1960s, the restrictions have been little by little removed, and now the Cabinet is accessible for adult visitors.

Nowadays, these frescoes are property of the state, and the Pompeiian lupanar is a protected World Heritage Site — strange, but true.

In the photo above: the fresco unearthed not long ago and depicting the Greek myth of Leda and the Swan.

‘And was the Last Day of Pompeii…’

The catastrophe started in October, 79 AD. For a long time, the date of the eruption was believed to be the 24th of August, but a graffiti on a wall found during the excavations says 17 October.Along with unprecedented earth shocks, Vesuvius spouted out of its throat a giant column of fire. The eruption was a bolt from the blue. A dense shower of ash and pumice (a type of porous rock of volcanic origin) became fatal for the city. Some people found their end in public places, others at home, but most citizens managed to escape from Pompeii.

Pliny the Younger’s description of the events is an eyewitness account.

‘Being got outside the houses, we halt in the midst of a most strange and dreadful scene. … We beheld the sea sucked back, and as it were repulsed by the convulsive motion of the earth… On the other side, a black and dreadful cloud bursting out in gusts of igneous serpentine vapour now and again yawned open to reveal long fantastic flames, resembling flashes of lightning but much larger. Ashes now fell upon us, though as yet in no great quantity. I looked behind me; gross darkness pressed upon our rear…

some were… praying to die, from the fear of dying; many lifting their hands to the gods, but the greater part imagining that there were no gods left anywhere, and that the last and eternal night was come upon the world.'

‘Being got outside the houses, we halt in the midst of a most strange and dreadful scene. … We beheld the sea sucked back, and as it were repulsed by the convulsive motion of the earth… On the other side, a black and dreadful cloud bursting out in gusts of igneous serpentine vapour now and again yawned open to reveal long fantastic flames, resembling flashes of lightning but much larger. Ashes now fell upon us, though as yet in no great quantity. I looked behind me; gross darkness pressed upon our rear…

some were… praying to die, from the fear of dying; many lifting their hands to the gods, but the greater part imagining that there were no gods left anywhere, and that the last and eternal night was come upon the world.'

‘…the first day for the Russian brush’

All this we can see splendidly rendered in the celebrated canvas by Karl Bryullov, a genius of Russian painting. By the way, prior to starting his work, he had studied Pliny the Younger’s letters and other historical records related to the ruin of Pompeii and Herculaneum.

The last day of Pompeii

1830-th

, 465.5×651 cm

The events of that long-gone fatal day were a challenging subject for quite a number of painters: Aivazovsky, Valenciennes, Gavin Hamilton, John Martin. But Bryullov depicted something more than a mere tragedy. As Gogol noted, the canvas showed all the ‘supreme physical and moral perfectness' of the human soul facing death: not only desperate attempts to escape, but people’s wish to embrace their children for the last time, to rescue their near and dear ones.

Italy could not but love Bryullov, who had created such portraits of its sons and daughters. It was the first time that the brilliance of the Russian brush had won European acclaim. The canvas was a sensation in Rome, Milan, Paris, and later, in Petersburg where it was acknowledged to be the best Russian painting of the nineteenth century.

Italy could not but love Bryullov, who had created such portraits of its sons and daughters. It was the first time that the brilliance of the Russian brush had won European acclaim. The canvas was a sensation in Rome, Milan, Paris, and later, in Petersburg where it was acknowledged to be the best Russian painting of the nineteenth century.

Risen from the ashes

Pompeii was accidentally discovered in the early seventeenth century during the digging of an underground channel. Step by step, the city was unearthed from under its volcanic covering. By the way, at first it was considered to be not Pompeii, but Stabiae. The first objects found there were sent directly to the museum in Portici — or destroyed, which hampered the research and damaged the city’s original aspect. A lot of frescoes were taken from the Pompeiian Temple of Isis to the Archaeological Museum in Naples. Only in 1760—1804, under the direction of Franscisco la Vega, the excavations were carried out in a better-organised way.Since 1863, when Giuseppe Fiorelli took charge of the excavations, the cutting-edge research methods of those days started being introduced. A street map was made, in which the city was divided into districts and the houses numbered. Perhaps, it lacked accuracy, but to orientate oneself in the site, it proved helpful. It turned out that the place had been conserved exactly as it had looked just before the eruption — largely due to hot lava that had surged about the city, drowned all its buildings, and stopped the access of oxygen to them. It sounds paradoxical, but the eruption that put an end to the city, kept it intact through centuries, and made it world famous.

Flora

I century

It is wonderful how undamaged the Pompeiian frescoes are. Normally, paints, even if they have been conserved like they were in Pompeii, cannot but lose their original shine. But the colours of the Pompeiian murals have retained all their brightness! Frescoes like those are found nowhere else. It is believed that ancient artist employed techniques the details of which, even nowadays, remain a secret (see the photo below).

So simply executed are the frescoes, but with so remarkable virtuosity that Renoir, while visiting Pompeii in 1881, was amazed.

‘A tradesman or a courtesan wanted a house decorated. The painter honestly tried to put a little gaiety on the wall — and that was all. No genius; no soul-searching.'

New discoveries

The Pompeiian excavations are far from complete and are not going to become so in the nearest decades. After centuries of digging, the archaeological discoveries are still abundant.One of them was an ancient sanctuary — a lararium. Rooms like this in rich houses served as shrines where people worshiped lares — deities who were believed to protect their homes. The newly discovered room was given the name ‘the Enchanted Garden' (see the photo below). On its walls, there is a boar fighting strange beasts, two serpents, a weird dog-headed man, and a gorgeous peacock.

Nowadays, archaeologists are digging the fifth district. On 18 May 2018, they uncovered the ‘Alley of balconies,' called so for the original balconies of its houses.

Not long ago, the ‘House of Jupiter' was unearthed. There, a fresco has survived illustrating the myth of Aphrodite and her mortal lover Adonis.

Splendid bright frescoes are presented by the so called ‘House of the Dolphins.' Besides the dolphins, we can see there a swan, a deer, flowers, peacocks, partridges, fantastic creatures (see the photo below). And again — the Pompeiian red!

Not long ago, the ‘House of Jupiter' was unearthed. There, a fresco has survived illustrating the myth of Aphrodite and her mortal lover Adonis.

Splendid bright frescoes are presented by the so called ‘House of the Dolphins.' Besides the dolphins, we can see there a swan, a deer, flowers, peacocks, partridges, fantastic creatures (see the photo below). And again — the Pompeiian red!

It seems that the city of Pompeii, which is coming back to life as a colossal art object, is not going, so far, to stop revealing new and new treasures to the world.

Text by: Irina Frykina

Title illustration: a fresco from the Villa of Livia (Augustus's wife) in Pompeii (photo)

Title illustration: a fresco from the Villa of Livia (Augustus's wife) in Pompeii (photo)

我们建议阅读