Curators of the Royal Academy of Arts took inspiration from a remarkable exhibition shown in Russia just before Stalin’s clampdown. The organizers focused on the 15-year period between 1917 and 1932 when possibilities seemed limitless and Russian art flourished across every medium.

Left: Kuzma Petrov-Vodkin, Beside Lenin’s Coffin, 1924.

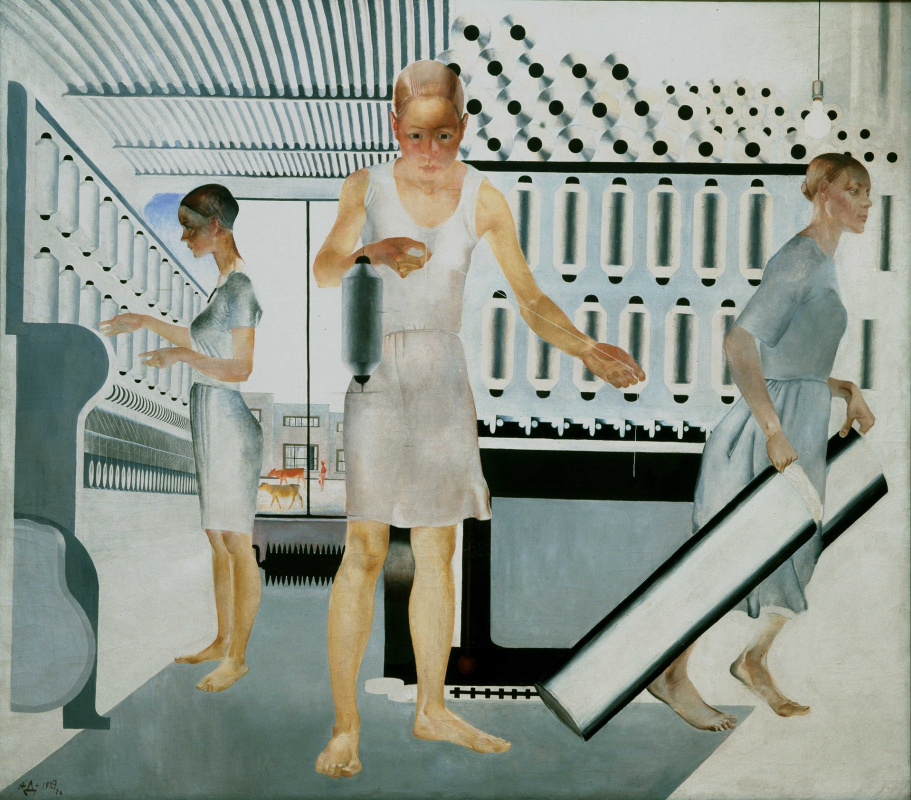

Exhibition includes photography, sculpture, filmmaking by pioneers such as Eisenstein, and evocative propaganda posters from a 'golden era' of graphic design.

Curators have tried to recreate the mode of life in apartments designed for communal living, filling the space with everyday objects ranging from ration coupons and textiles to brilliantly original Soviet porcelain.

Left: Unknown artist, Advertisement 'Of course, cream-soda!', 1926.

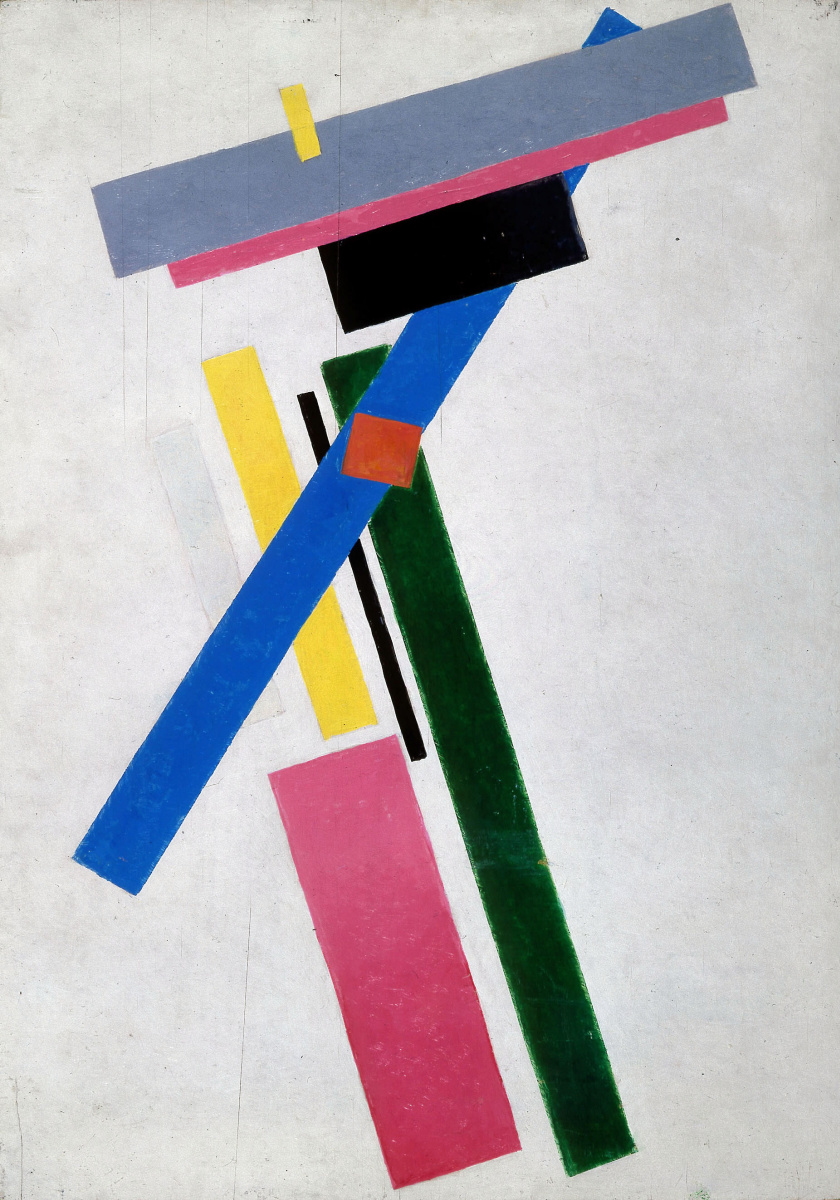

How was the post-revolutionary peasant to be depicted on canvases? In films, he was a hero tanned by the Soviet sun, singing merrily home after a day in the fields or grinning at the sight of a newfangled milking machine. But in paintings he might be different: from a war-scarred veteran to… an array of dazzling rectangles.

Malevich’s Red Square is one of such examples. In 1915 exhibition catalogue it had a subtitle: Painterly Realism of a Peasant Woman in Two Dimensions.

Left: Kuzma Petrov-Vodkin, After the Battle, 1923.