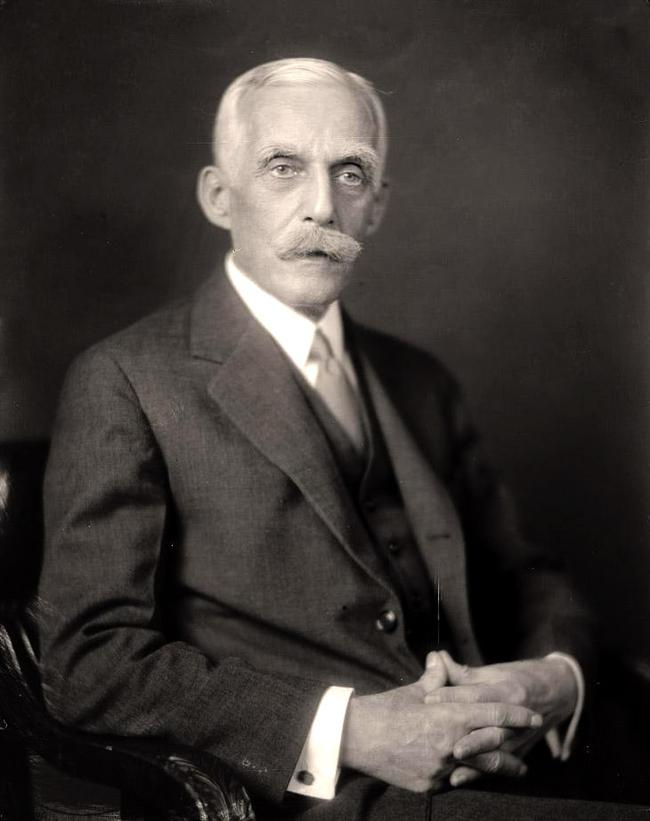

Andrew Mellon belongs to the unique generation of the first American billionaires. Henry Ford, John Davison Rockefeller, Andrew Carnegie and John Pierpont Morgan were also among those who became record-breakingly wealthy. Andrew Mellon was good friends and regularly played poker with a millionaire Henry Clay Frick, the founder of Frick Collection. Yet, Andrew Mellon wasn’t overshadowed by his friends: his uniqueness lied, firstly, in his "versatility", and secondly, in his perfectionism, paradoxically combined with personal modesty. Mellon succeeded in several spheres: as a banker and an industrialist, as a politician and a statesman, as a collector and a philanthropist.

It’s often argued who was the first man in the history of mankind who managed to leave his descendants a billion — Rockefeller or Mellon. However, even if Mellon had to give the palm of victory to Rockefeller, it was only because in the last decades of his life he spent a lot of money on paintings which, after being handed over to the National Gallery of Art, ceased to be Mellon’s private property.

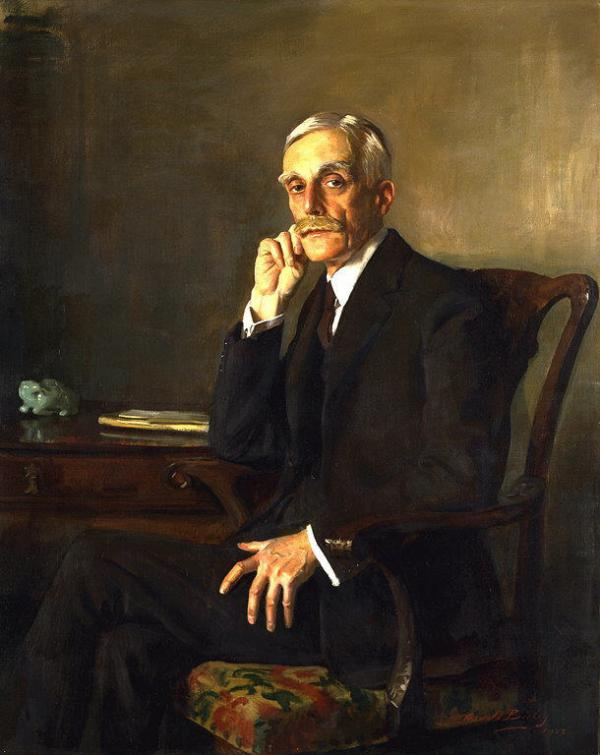

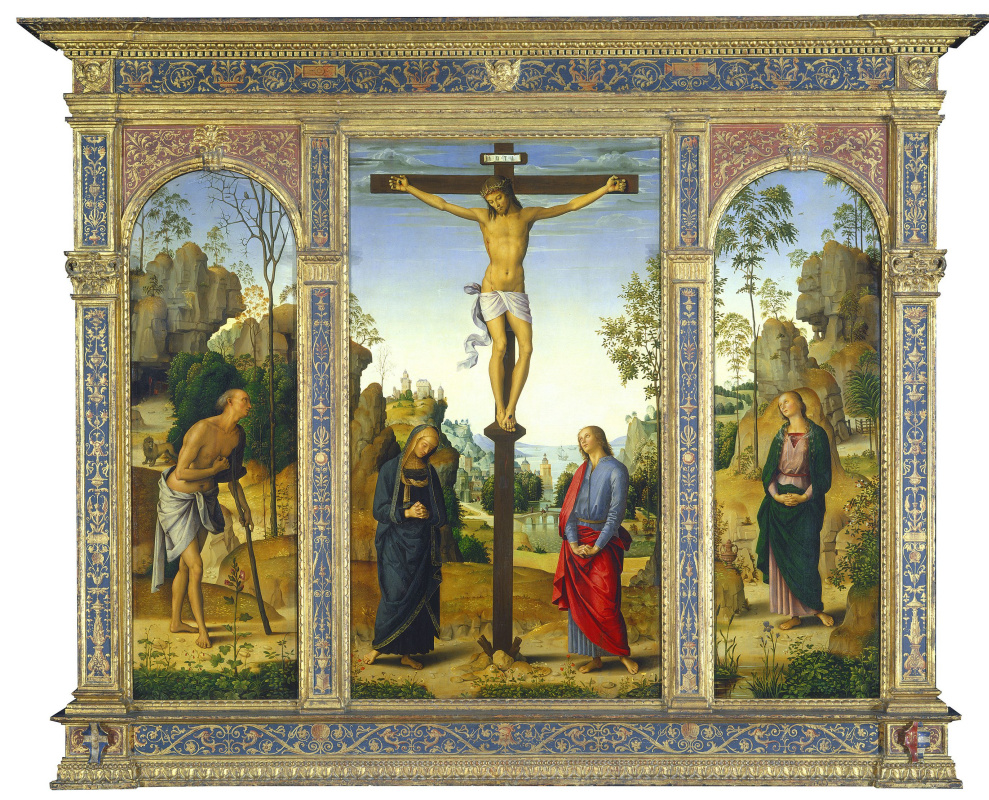

Some of the masterpieces from Andrew Mellon's collection:

Mellon from the Mellon's clan

The Scottish Protestants Mellons moved to northern Ireland in the middle of the 17th century, and in 1818, already considering themselves Irish, sailed to the United States. Andrew’s father Thomas Mellon was a banker, and later — a judge. While being a banker, Thomas Mellon came up with a legal way to grow rich by alienating property from those who didn’t have the opportunity to repay loans on time. Having been elected a judge, the elder Mellon left his business for a while, and his younger son Andrew would run away from school to sneak into his father’s sessions and hide under the bench, watching, listening and absorbing the casuistry of juridical intricacies.Andrew left the University of Pennsylvania, which he entered at the age of 13, to run a business. Thomas Mellon bought for him and his 15-year-old brother Richard a plot of land in Mansfield, gave them money to buy a lumber yard and left, giving teenagers the freedom to develop their own business — the way babies sometimes are being thrown into water to learn how to swim. The brothers "floundered" for a year and a half, but the business had to be closed down. Yet, already in 1870, Thomas Mellon founded the bank Mellon & Sons, which 27-year-old Andrew would head in 12 years.

Besides his ability not to be afraid to take risks, Mellon learned from his father one more lesson: you can only trust your family. The Mellons' business would always remain kind of clannish: when buying shares, Andrew always bought exactly the same number of them for Richard, and later — for Richard’s son William.

Andrew Mellon made his capital on aluminum, carborundum, oil and steel

The first industrial enterprises, in which the Mellon brothers began to invest, were aluminum factories. They didn’t establish new enterprises, but successfully invested in the already existing, but lacking funds ones and quickly got a controlling interest there. When aluminum began to yield a stable income, the Mellons decided on new speculative transactions.Once, a visitor came into Andrew Mellon’s waiting room and introduced himself: "Edward Goodrich Acheson, a chemist". At that time, Acheson headed the Carborundum Company and was famous for inventing the process of synthesizing silicon carbide (carborundum) — artificial diamond, the hardness of which is only slightly lower than that of the real one. Although Acheson’s enterprises already had some investments from Pennsylvania, he was interested in additional financial injections. During the conversation, Acheson beat around the bush, as if he was nervous, and kept mechanically fiddling with a glass paperweight from Mellon’s desk. Suddenly, he pulled a large stone out of his pocket and used it to make a cut on the surface of the paperweight. Andrew Mellon was impressed: "Where did you manage to get this gorgeous diamond?" "I created it," Acheson responded modestly.

Taking projects that discreet businessmen would find too adventurous, the Mellons began buying up shares of Acheson’s company, quickly increasing their share to 46.6 percent, and soon after acquiring a controlling interest. In the end, the Mellon clan fired the company’s founder and president Acheson, because, in their opinion, he wasn’t good at management and began to slow down the company’s potential, so they replaced him with their auditor Frank W. Haskell. And although from an ethical point of view this reshuffle wasn’t perfect, their business stood to gain from it: Carborundum Company began to gain momentum rapidly.

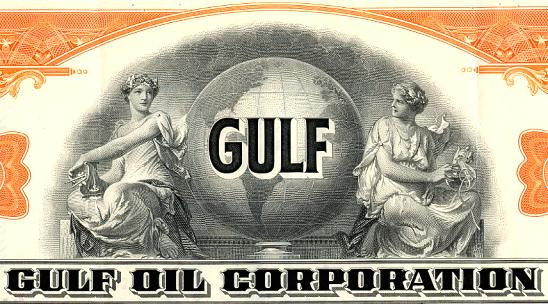

Yet, it was oil that earned the Mellons the largest profit. The idea with oil originally belonged to Mellon’s nephew William, Richard’s son, who decided to become an oil agent. The task of such an agent was to find unexplored oil fields and persuade the farmers, in whose plots the oil was found, to allow the extraction on their land for a certain percentage (about one eighth of the profit). Having seen William’s enthusiasm, Richard and Andrew Mellon financed his activities, and soon the Mellons' oil rigs were all over Pennsylvania, Ohio and West Virginia.

At first, the Mellons sold the extracted oil to the Rockefellers, but Andrew realized that the one "skimming the cream" off crude oil was the one controlling all the components of the technological chain — from transportation to processing and subsequent marketing. For these reasons, they bought several oil refineries in Pennsylvania, which under the Mellons' patronage turned into direct competitors of Rockefeller’s Standard Oil. By the beginning of the 1890s, their share in U.S. oil exports reached ten percent!

Since the early 1900s, the oil corporation Gulf Oil has become one of the core assets of the Mellon clan.

From the entrepreneur to the treasurer: Andrew Mellon's reforms as United States Secretary of the Treasury

Despite his aggressive, invasive style of making profit, Mellon wasn’t really after publicity, which is proved by the fact that when in 1921 the elected president Warren Harding was offered to appoint him as Secretary of the Treasury, he, as legend has it, asked: "Who is Mellon?" The piquancy of the situation is that, according to some sources, Mellon’s money was one of the main sources of financing the new president’s election campaign. Investing through a chain of intermediaries (in this case — through the bigwigs of the Republican Party) seemed to Mellon far more far-sighted tactics than constantly appearing in the press. Mellon adhered to the same principle of investing funds not directly, but through intermediaries when he started buying up the Hermitage’s treasures.Mellon served as Secretary of the Treasury for 11 years, remaining the chief financier of the United States under three presidents — Harding, Coolidge and Hoover. Accused of financial fraud and tax evasion, Mellon would leave only under Franklin Delano Roosevelt, but his reforms allowed America to maintain world leadership in living standards for a long time.

One of Mellon’s main achievements was a significant tax cut. Within the first 5 years of his work, the income tax over $1 million decreased from 66 to 20 percent; for small businesses Mellon developed a balanced tax system that would be both feasible for honest taxpayers, and not loss-making for the state, which spurred the American economy. Under Mellon, the external debt of the United States fell from 26 to 16 billion. The growth of the GNP reached 40%, while the unemployment rate, inflation and loan rates were lower than ever. Mellon was referred to as the "greatest Secretary of the Treasury since Alexander Hamilton."

Mellon even wrote a book on taxes, in which he outlined his philosophy: "Any man of energy and initiative in this country can get what he wants out of life. But when that initiative is crippled by legislation or by a tax system which denies him the right to receive a reasonable share of his earnings, then he will no longer exert himself and the country will be deprived of the energy on which its continued greatness depends."

Only the fourth president in Mellon’s state career — Franklin Delano Roosevelt — would dismiss him from his post in 1933, making his fellow Democratic party member new Secretary of the Treasury, and Mellon — the United States Ambassador to the United Kingdom.

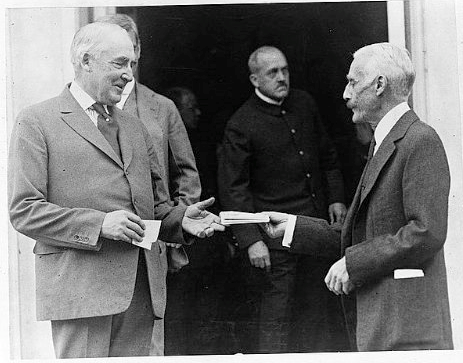

Andrew Mellon (right) and the 29th US President Warren Harding.

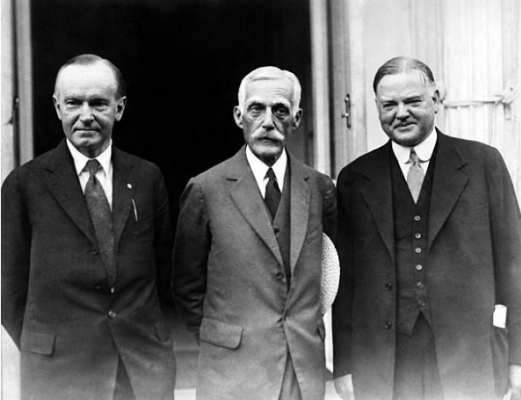

Andrew Mellon (center) between the 30th President of the United States Calvin Coolidge and the 31st one — Herbert Hoover.

Andrew Mellon's collection

The last thing Mellon looked like was a sentimental, insane art freak. He was never directly engaged in tracking, searching or buying masterpieces, never bought paintings from private parties. Moreover, he got really interested in painting rather late — when he was already able to afford a lot. Mellon got into collecting thanks to his friend Henry Clay Frick, with whom he made a trip to Europe in search of entertainment and new markets.Unlike most neophyte collectors with unlimited finances, Mellon started buying paintings not by the Italian artists, but by the British and the Dutch ones. It might be due to Mellon’s Scottish-Irish origin, but he began with purchasing paintings by British artists Thomas Gainsborough and Joshua Reynolds and by the classic of the Scottish school of painting Henry Raeburn, whose works decorated his new apartment in Washington. "At first, Mellon showed excessive fastidiousness in the choice of works," wrote Marco Carminati. "From the first purchase, he demonstrated exceptional adherence to serious paintings, such as English portraits and Dutch landscapes. At the same time, Mellon was not into bright, colourful canvases. He respected, or even worshipped the artworks to such an extent that paintings on religious subjects were never placed in the rooms where Mellon was smoking and drinking with friends."

In the late 1920s, Mellon found another "gold mine" - the Hermitage Museum in St Petersburg, just like his nephew once discovered oil deposits. Those were secret sales of Hermitage treasures, undertaken by the Soviet government to get money for the industrialization of the country, which became the most abundant source of masterpieces for Mellon’s collection.

The first transaction, secretly concluded in favour of Mellon by the British antiquarians in March 1930, made him the owner of Van Dyck’s painting Philip, Lord Wharton. The price paid was 250 thousand pounds sterling. A successful start inspired Mellon to continue, and with the help of the same intermediaries, the Hermitage handed Mellon three more paintings: Portrait of a Young Man by Hals, The Girl with a Broom by Rembrandt (575 thousand pounds for both) and the portrait of Rubens' wife Isabella Brandt by van Dyck (223 thousand pounds).

This, however, did not stop the Soviet Ministry of Foreign Trade, which continued to sell paintings to the millionaire. The Hermitage Annunciation by Jan van Eyck cost Mellon half a million dollars in May 1930. And it was immediately followed by the "asymmetric answer" of Mellon as civil servant: arguing that the Soviet authorities use the labour of prisoners in logging operations, the US Secretary of the Treasury imposed an embargo on the import of all types of timber from the USSR.

Raphael’s paintings The Large Cowper Madonna and The Alba Madonna (being part of the Hermitage collection in 1836−1931) on permanent display at the National Gallery of Art in Washington.

Andrew Mellon is a founder of the National Gallery of Art in Washington

Mellon came up with the idea of creating a gallery in 1927, before the epic with the Hermitage, which by no means was his only source of artwork. All Mellon’s purchases, including the most valuable works of European art from the Byzantine era to the end of the 18th century, for a long time needed a separate room that could best display them to the public. But Mellon wasn’t going to create a "museum under his own name" like his friend Henry Clay Frick did.Mellon thought that the level of his collection allowed it to form the basis of the national one, and America would have its own museum, similar to the National Gallery of London and capable of competing with the Parisian Louvre with a purely American juvenile ardour. Mellon approached the US authorities with a proposal: he was ready to sacrifice his collection, provided that the state would put up a building, corresponding to such an ambitious task, and subsequently take care of the National Gallery of Art in Washington.

In a separate paragraph, it was specified: "the gallery would display no works of art unless 'of similar high standard of quality' to those already in the Mellon collection."

Mellon’s contribution was priceless: 120 paintings and 21 sculptures from his own purchases formed the core of the National Gallery’s collection. Still, Mellon didn’t want the museum to be called after him. It was not only about Mellon’s commendable modesty, but also about rational calculation: if the gallery belonged to "all at once and to no one individually", then other rich donators would be able to follow Mellon’s example. And it actually happened: soon, Samuel Henry Kress donated much of his art collection to the National Gallery — and occupied 34 halls of the new building with his paintings, including the rare Adoration of the Shepherds by Giorgione and Death and the Miser by Hieronymus Bosch, as well as paintings by El Greco, Rubens, van Dyck, Lorenzo Lotto, David, Ingres and Watteau. Later, Peter Widener, Chester Dale, Barbara Hutton and others also donated paintings to the collection of the National Gallery. This process continues to this day.

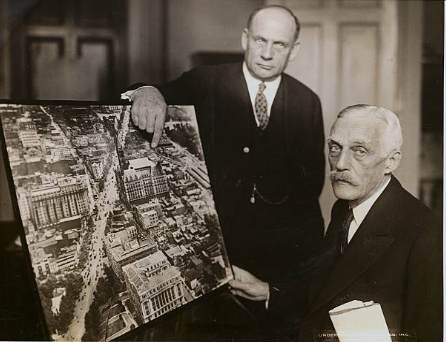

Andrew Mellon in front of the miniature of the National Gallery of Art in Washington.

Andrew Mellon and John Russell Pope with the design of the National Gallery building.

Mellon at the groundbreaking ceremony of the National Gallery of Art in Washington.

The construction of the gallery, the largest marble structure in the world, was completed in 1941 and accepted by President Franklin D. Roosevelt on behalf of the American people. The museum wasn’t named after Mellon, nor did the monument appear; and yet, Mellon never really wanted it to happen. However, there appeared The Andrew W. Mellon Memorial Fountain just north of the National Gallery of Art and US postage stamp of him.

Andrew Mellon's private life

Legend has it that before Andrew Mellon’s death, his son Paul asked to give him a painting by the French artist Camille Corot (from his father’s own collection), and in response the dying Mellon suggested that he buy that painting. They said that the famous financier’s passion for making money went to ridiculous lengths. However, this story clearly contains more slander than truth: Mellon donated a lot to charity, often doing it anonymously, and adored his children — son Paul and daughter Ailsa.

Mellon’s children Ailsa and Paul were his joy: he would stop playing poker and join children’s games at their slightest request. At the same request of his children, the multimillionaire would obediently visit 10 Cent Stores with them and was happy to participate in their teenage naughtiness. Not least because of this, Mellon’s children became interested in art. Soon after Mellon’s death, both of his children established a foundation — Ailsa’s one was called Avallon, and Paul’s one — Dominion, and in June 1969, both organizations were consolidated into The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, successfully functioning today (and even collaborating with the State Hermitage Museum). Moreover, Paul Mellon founded the Yale Center for British Art. Mellon’s children stepped into their father’s shoes and brought several paintings from the family collection to the National Gallery of Art in Washington: for example, in remembrance of their father, Ailsa donated A Young Girl Reading by Jean-Honoré Fragonard and Paul — Woman with a Parasol by Claude Monet.

Andrew Mellon in his office

Author: Anna Vcherashnia