We have selected 5 best books written in different genres, at different times, with different research goals — so that you take a convenient approach to Impressionism and really understand everything.

The Bible: John Rewald. The History of Impressionism

Different paintings were used on the covers of various editions of Rewald’s book. But each of them had Monet as a central figure. From left to right: Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Claude Monet Painting in his Garden at Argenteuil; Claude Monet, The Rue Saint-Denis, Celebration of June 30, 1878 and Woman in the Garden. Sainte-Adresse.

Author: Only six years had passed after the death of the last French Impressionist painter, Claude Monet, when John Rewald graduated from the Sorbonne and wrote his dissertation. His scientific work was devoted to the friendship of Cézanne and Zola. Rewald became the first life-long researcher of Impressionism and Post-Impressionism

in the world, editor of the first published letters of Cézanne, Pissarro and Gauguin, Renoir's drawings and sculptures by Degas, as well as the author of several biographies. He took photographs of the places in Aix-en-Provence, where Cézanne painted his most famous and important works, kept the artist’s studio and took part in the creation of the museum there, and finally, was buried close to Cézanne. You can even find a plaza in Aix that was named after him.

Book: Even if you have read modern biographies of all Impressionist artists, be it a volume about each of them, John Rewald’s History of Impressionism will still remain useful for people with any amount of knowledge. He created a well-composed, rich (astounding in the amount of information collected) biography of the art movement in whole. The book covers a strictly defined period: from the day when Impressionism was born, until the day when Impressionism

died. That is, from the first to the eighth (last) exhibition of the "Anonymous Society of Painters, Sculptors, and Engravers." Time in the book passes realistically, moving from one event to another. Reading Rewald’s book, it is easy to see how Monet slid into poverty, while Manet was spending his summer in Montgeron and grumbling at the Salon, and how Renoir introduced Chocquet to Cézanne. Rewald promises the reader to give a "full report" on the origin and development of the movement — and fulfills his promise.

Most valuable: or rather, invaluable in the epic book The History of Impressionism is the writer’s objective, tactful and composed point of view. Rewald does not have a central figure, as it often happens with private biographies, around which the narrative revolves, there are no attempts to justify someone or make them look good.

Quote: "The exhibition opened on April 15, 1874. It was supposed to last one month and was open from ten to six, and, which was also an innovation, from eight to ten in the evening. They charged one franc to get in and fifty centimes for a catalogue and to the media. The exhibition seems to have been well attended at first, but the public went there mainly to laugh. There was a joke going around about the artist’s method of painting, which was to load a pistol with several tubes of paint and fire them at the canvas, finishing it off with their signature."

Drawbacks: the methodical, meticulous Rewald sometimes makes his reader yawn with his meager list of already forgotten artists, writers and critics, whose names are important in the overall picture of the impressionist world. His stories slow down and lose puff when the author feels the need to specify a list of paintings displayed at some of the exhibitions. But the status of the pioneer justifies Rewald in this naked outline of facts and tediousness of his research: we must understand that at the time of the book’s creation, it was the first time when all this was written about.

Quote: "The exhibition opened on April 15, 1874. It was supposed to last one month and was open from ten to six, and, which was also an innovation, from eight to ten in the evening. They charged one franc to get in and fifty centimes for a catalogue and to the media. The exhibition seems to have been well attended at first, but the public went there mainly to laugh. There was a joke going around about the artist’s method of painting, which was to load a pistol with several tubes of paint and fire them at the canvas, finishing it off with their signature."

Drawbacks: the methodical, meticulous Rewald sometimes makes his reader yawn with his meager list of already forgotten artists, writers and critics, whose names are important in the overall picture of the impressionist world. His stories slow down and lose puff when the author feels the need to specify a list of paintings displayed at some of the exhibitions. But the status of the pioneer justifies Rewald in this naked outline of facts and tediousness of his research: we must understand that at the time of the book’s creation, it was the first time when all this was written about.

Who is who and what is what: Jean-Paul Crespelle. La Vie Quotidienne Des Impressionnistes (Daily Live Of The Impressionists)

Paintings from the book covers: Argenteuil by Édouard Manet, Paul Helleu Sketching With His Wife by John Singer Sargent, Dance at Bougival by Pierre-Auguste Renoir.

Author: In the first place, Jean-Paul Crespelle was a journalist who wrote articles about art for several popular French newspapers. And his books about the daily life of Montmartre and Montparnasse in the early 20th century, as well as about the life of the Impressionists, are written in the spirit of investigative journalism.

Book: Jean-Paul Crespelle chose an arbitrary chronological framework for his book — beginning with the 1863 Salon des Refusés, where Édouard Manet’s scandalous Luncheon on the Grass was first displayed, and ending with the death of Manet himself. But Crespelle did not care about the exact dates and historical sequence — he organized the space of his book in other way. It was more interesting for him to mark on the map of France and the world the places visited by the Impressionists, delve into their menus, bills and dressing rooms, and eavesdrop on conversations at friendly gatherings. What were the theatrical performances and balls at Gleyre’s studio like? Where did the young Monet, Renoir and Bazille study ? How much did the "always broke" Monet really earn compared to a clerk or a doctor? And even who was that famous photographer Nadar, who generously provided his studio for the first Impressionist Exhibition? And also which of Mane’s mistresses was frigid, which artist himself was impotent, and whose love was truly platonic?

Book: Jean-Paul Crespelle chose an arbitrary chronological framework for his book — beginning with the 1863 Salon des Refusés, where Édouard Manet’s scandalous Luncheon on the Grass was first displayed, and ending with the death of Manet himself. But Crespelle did not care about the exact dates and historical sequence — he organized the space of his book in other way. It was more interesting for him to mark on the map of France and the world the places visited by the Impressionists, delve into their menus, bills and dressing rooms, and eavesdrop on conversations at friendly gatherings. What were the theatrical performances and balls at Gleyre’s studio like? Where did the young Monet, Renoir and Bazille study ? How much did the "always broke" Monet really earn compared to a clerk or a doctor? And even who was that famous photographer Nadar, who generously provided his studio for the first Impressionist Exhibition? And also which of Mane’s mistresses was frigid, which artist himself was impotent, and whose love was truly platonic?

Most valuable: the book absolutely lives up to the task stated in its title — no art criticism, only real stories, emotions and everyday habits, successfully packed into thematic chapters.

Quote: "Renoir, an easy-going and quite a kind man, hated Gauguin — both as a person and an artist. Having learned of his departure to Tahiti, he remarked: "An artist might paint as well in the Batignolles as in Tahiti". Even though Cézanne loved Renoir, he still could not stand his friend’s disrespectful statements about the bankers during their joint stay in Jas de Bouffan. This was tantamount to talking about the rope in the house of a hanged man. Yet, both of them didn’t like Van Gogh, and it was Cézanne who convinced Vollard to quickly get rid of his collection of paintings by the brilliant Dutchman!"

Drawbacks: familiarity and questionable awareness of the intimate thoughts and causes of the artists' actions. This writing facility, however, turns out to be excusable and sometimes even funny.

Quote: "Renoir, an easy-going and quite a kind man, hated Gauguin — both as a person and an artist. Having learned of his departure to Tahiti, he remarked: "An artist might paint as well in the Batignolles as in Tahiti". Even though Cézanne loved Renoir, he still could not stand his friend’s disrespectful statements about the bankers during their joint stay in Jas de Bouffan. This was tantamount to talking about the rope in the house of a hanged man. Yet, both of them didn’t like Van Gogh, and it was Cézanne who convinced Vollard to quickly get rid of his collection of paintings by the brilliant Dutchman!"

Drawbacks: familiarity and questionable awareness of the intimate thoughts and causes of the artists' actions. This writing facility, however, turns out to be excusable and sometimes even funny.

A Perfect Biography: Jean Renoir. Renoir, My Father

On the covers — paintings by Auguste Renoir: Self-portrait, The Garden In The Rue Cortot At Montmartre (detail) and Lunch at the Restaurant Fournaise (detail with the artist’s self-portrait).

Author: Jean Renoir is the same long-haired boy who was stitching a dress for his toy camel, drawing, playing and simply posing for many of his father’s paintings. Renoir’s favourite model with golden hair, a boy who grew up and married his father’s young sitter. A few years ago, they shot a film about that in France. Jean Renoir himself is one of those rare children whose talent, well-deserved fame and recognition are equal to those of their parents. He’s considered one of the five best directors in the world, and two of his works are on the list with the same monumental coverage — "hundred best films of all time." In 1975, Renoir received the Academy Award for his contribution to the motion picture industry.

Jean Renoir in front of his father’s painting. 1959. Source: photo.ina.fr

Book: The rare case when a person with an invaluable amount of personal information about the artist is also an excellent storyteller who can systematize and "direct" this information. Several pages describing the changes in the world from Renoir’s birth to his twilight years can replace Crespelle’s entire book on everyday life. Talks about painting, women, countries, life philosophy, which Jean heard from his father personally, are combined with the stories of other artists, next to which the author grew.

Most valuable: Auguste Renoir is portrayed so up close that after reading the book, readers can feel like they personally knew the artist.

Quote: "Here is a list of some of the things that he unconditionally considered "poor": bright-green trimmed English lawns, wheat bread, polished floors, everything made of rubber; statues and buildings of Carrara marble that was "suitable only for cemeteries"; meat stewed in a pan; sauces with flour; food colorings; fake fireplaces painted with black lacquer; sliced bread (he liked to break it into pieces); fruit, peeled with a steel-bladed knife (he preferred a silver one); broth with fat; cheap wine in a bottle with a colorful label and a fancy name; footmen, serving in white gloves to hide their dirty hands; furniture covers and even more — chandeliers; brushes for bread crumbs; books, summarizing a writer or a scientific question or clarifying the history of art in several chapters, and at the same time — illustrated and periodical magazines, pavements and houses made of concrete; asphalt on the streets; cast objects; bedsheets with prints; central heating, in other words — "even heat"; this category also included mixed wines; mass production items; ready-made clothes; moulages on ceilings and cornices; wire mesh; animals standardized by rational breeding methods; people standardized by upbringing and education."

Drawbacks: In Jean Renoir’s book, you won’t find a single word about his father’s questionable relationships, love affairs, flirtation or his unpopular anti-Semitic views. This is a biography written by an admiring, intelligent, sensitive and delicate son.

Quote: "Here is a list of some of the things that he unconditionally considered "poor": bright-green trimmed English lawns, wheat bread, polished floors, everything made of rubber; statues and buildings of Carrara marble that was "suitable only for cemeteries"; meat stewed in a pan; sauces with flour; food colorings; fake fireplaces painted with black lacquer; sliced bread (he liked to break it into pieces); fruit, peeled with a steel-bladed knife (he preferred a silver one); broth with fat; cheap wine in a bottle with a colorful label and a fancy name; footmen, serving in white gloves to hide their dirty hands; furniture covers and even more — chandeliers; brushes for bread crumbs; books, summarizing a writer or a scientific question or clarifying the history of art in several chapters, and at the same time — illustrated and periodical magazines, pavements and houses made of concrete; asphalt on the streets; cast objects; bedsheets with prints; central heating, in other words — "even heat"; this category also included mixed wines; mass production items; ready-made clothes; moulages on ceilings and cornices; wire mesh; animals standardized by rational breeding methods; people standardized by upbringing and education."

Drawbacks: In Jean Renoir’s book, you won’t find a single word about his father’s questionable relationships, love affairs, flirtation or his unpopular anti-Semitic views. This is a biography written by an admiring, intelligent, sensitive and delicate son.

A New Take: Alex Danchev. Cézanne: A Life

Author: Alex Danchev is a British historian, professor, officer and translator. His areas of interest are international relations, political analytics and art. Danchev’s coordinate system includes art and artists — the figures that influence the course of world history.

Alex Danchev. Source: slippedisc.com

Book: Cézanne can’t be considered an Impressionist, he was always different and painted rather at the same time than together with them. Nonetheless, the book Cézanne: A Life is an absolute must-read for impressionistic collection. This is a rich, modernly-written book aimed at a reader who is used to dealing with huge amount of information, systematizing it while reading and immediately looking for possibilities for its permanent use. Here, you will find a subtle and consistent art criticism that includes later reactions, interpretations, and points of view. A careful sorting of Cézanne's personal conversations and letters will add to the artist’s portraiture. This concentrated story makes the reader slightly dizzy, the work of the author seems inhuman, but the image of the new Cézanne — an intellectual, a philosopher, and a sage — is a reward for this informational vertigo.

Most valuable: an orderly debunking of Cézanne's textbook image of the barbarian, savage and hysteric, and in return — the new Cézanne, who is an understanding, intelligent and sensitive man of principle.

Quote: "Cézanne and Pissarro told each other the truth in painting. That is a rare distinction, and they knew it. Theocritus tried for ten years to lure Hesiod to the country of his muses and the mountain he made his own. Pissarro was immovable. For Cézanne, that must have come as a bitter disappointment. The relationship did not fail; but from now on, except for brief interludes, it would be conducted at a distance. Voluntarily or involuntarily, Cézanne pushed on alone. A pattern of sorts was beginning to emerge."

Drawbacks: Danchev almost always masterfully draws historical and ideological parallels between the life of Cézanne and other famous personalities. But while the author’s search for the shared fields between Cézanne and Flaubert is quite reasonable, his method of explaining Cézanne's relationship with his father (using the similar story of Franz Kafka) seems unreasonable.

Quote: "Cézanne and Pissarro told each other the truth in painting. That is a rare distinction, and they knew it. Theocritus tried for ten years to lure Hesiod to the country of his muses and the mountain he made his own. Pissarro was immovable. For Cézanne, that must have come as a bitter disappointment. The relationship did not fail; but from now on, except for brief interludes, it would be conducted at a distance. Voluntarily or involuntarily, Cézanne pushed on alone. A pattern of sorts was beginning to emerge."

Drawbacks: Danchev almost always masterfully draws historical and ideological parallels between the life of Cézanne and other famous personalities. But while the author’s search for the shared fields between Cézanne and Flaubert is quite reasonable, his method of explaining Cézanne's relationship with his father (using the similar story of Franz Kafka) seems unreasonable.

A Family Story: Edmund de Waal. The Hare With Amber Eyes

Author: Edmund de Waal is a British ceramicist who has titles, exhibitions, a name and some deepest immersion in the philosophy of his own profession. You wouldn’t believe it, but even though he was appointed Officer of the Order of the British Empire

, he stubbornly keeps calling himself a potter. Waal wrote only one book, laying no claim to be a historian, art historian or writer, but became the hero of all British newspapers writing about literature and art.

Edmund de Waal with his collection of netsuke that inspired him to write a book. 2011 Source: edmunddewaal.com

Book: Edmund de Waal created a well-composed travel book, following his favourite hare with amber eyes and other netsuke figures, which he inherited from his great-uncle, and which spent 150 years moving from one to another member of the Ephrussi dynasty. Having abandoned the potter’s wheel for two years, Edmund spent every day putting one of his 264 ancient Japanese figures into his pocket and setting off in search of the former mansions of his great-grandfathers, archival publications in European libraries and people who remembered something. This is a book about Japan and the universal fashion for everything Japanese in the 19th century Paris, about bankers, weddings, the little exploits of the already forgotten people, the huge Jewish tragedy in Vienna in the middle of the 20th century and about despair. The balance of wit, admiration, research passion, eloquence and accuracy makes The Hare a perfect book about one family, several eras, art, war and oriental philosophy.

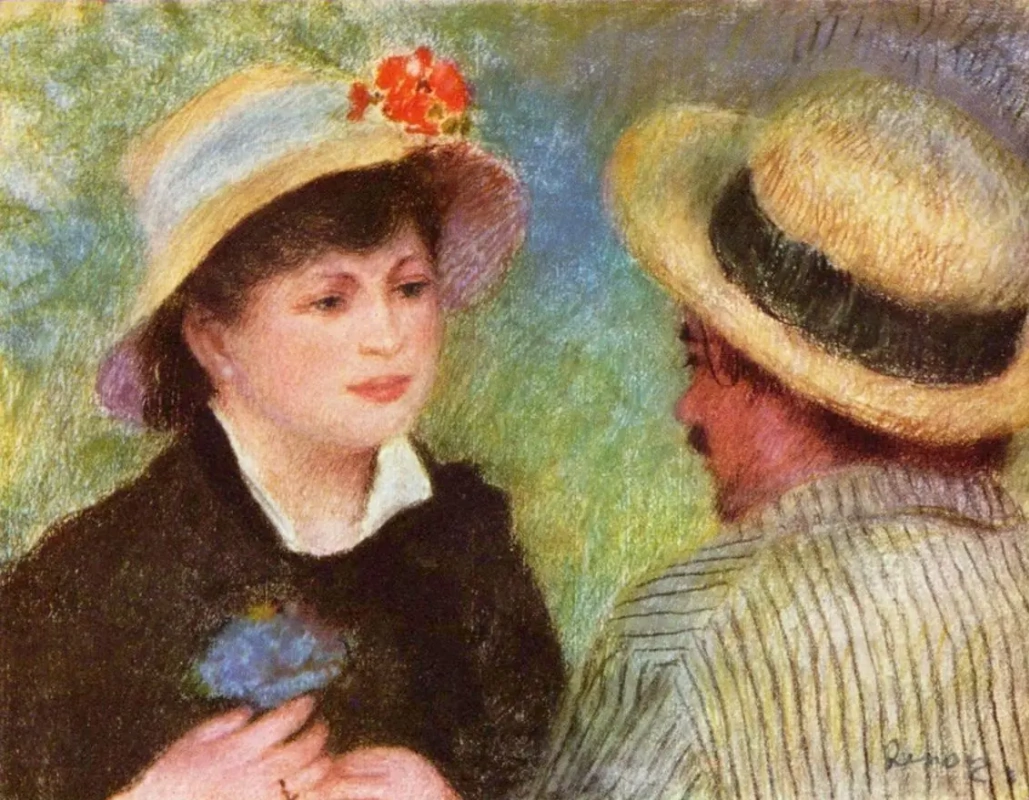

Luncheon of the boating party

1881, 129.5×172.7 cm

In Renoir’s painting Luncheon of the Boating Party, one can see the most famous Ephrussi, Charles — patron of arts, critic and art historian, who became the prototype for Swann in Marcel Proust’s novel. The man in the top hat is Charles Ephrussi.

Untwisting the webs of life bonds, the intertwinement of personal stories and world tragedies, Waal found traces of the people depicted in the paintings of the Impressionists. The girl in blue from Renoir’s painting was deported by the Germans and died in Auschwitz.

Most valuable: Edmund de Waal’s book characters and family members achieved so much and got into such historical maelstroms that life of every single one of them deserves a separate novel to be written about. But the author manages to find touching, funny, heroic stories of people, cities and nations even outside of his family and combines them into a living, moving organism.

Quote: "I push my way through the students and I’m on the Ringstrasse, and I can move and can breathe. Except that it is a windingly ambitious street, breathcatchingly imperial in scale. It is so big that a critic argued, when it was built, that it had created an entirely new neurosis, that of agoraphobia. How clever of the Viennese to invent a phobia for their new city."

Drawbacks: hardly any — except perhaps that this book is not entirely about Impressionism . Of course, you can read only the "impressionist" part (it happens to be the first one), but you’ll have to immediately get rid of the book, give it away or take it to the country house — otherwise it will be difficult to put it away.

Quote: "I push my way through the students and I’m on the Ringstrasse, and I can move and can breathe. Except that it is a windingly ambitious street, breathcatchingly imperial in scale. It is so big that a critic argued, when it was built, that it had created an entirely new neurosis, that of agoraphobia. How clever of the Viennese to invent a phobia for their new city."

Drawbacks: hardly any — except perhaps that this book is not entirely about Impressionism . Of course, you can read only the "impressionist" part (it happens to be the first one), but you’ll have to immediately get rid of the book, give it away or take it to the country house — otherwise it will be difficult to put it away.