Natalia Goncharova immersed into traditional art so deeply that her paintings looked like works of folk artisans. Vivid images that fascinated the artist in her youth, later, alas, were practically supplanted by total party-approved socialist realism

. However, the unrestrained, bold and innovative painting manner of the young Goncharova, fortunately, has been preserved. In 2019, the London Tate Modern Gallery payed tribute to her by presenting for the first time in the UK the largest retrospective of her oeuvre. We have prepared some facts about the artist, who influenced the main trends in the art of the twentieth century.

Anticipating the details, let’s recall that Natalia Goncharova, the artist is the cousin of another Natalia Goncharova, who was the great-granddaughter of the wife of famous Russian poet Alexander Pushkin.

Self-portrait with yellow lilies

1907, 77×58.2 cm

1. From sculpture to painting: when three days decide everything

The first to discern artistic genius in Natalia Goncharova was Mikhail Larionov. They had a lot in common: they were born the same year, their families moved to Moscow the same year, the same year the future artists entered the school of painting, sculpture and architecture. There they have met. Goncharova studied to be a sculptor, Larionov was to be a painter. And Larionov was the first to tell Goncharova: you are a painter, "you have eyes for colour, and you are busy with shape. Open your eyes at your own eyes!" this is how Marina Tsvetaeva describes the Natalia’s transition from sculptural to pictorial images.

Natalia Goncharova. "Phoenix" (Polyptych "Harvest"), 1911

Photo © ADAGP, Paris and DACS, for theguardian.com

Photo © ADAGP, Paris and DACS, for theguardian.com

Goncharova heard, felt, and really "opened her eyes" to the colour — which didn’t hold her from raising a stink with Larionov. However, in those three days after the disagreement, until the artists saw each other, the painter was born from the sculptor. Goncharova filled her room with a huge number of drawings, and she could not stop — she painted, enjoyed the colour, form, the ability to immediately express thoughts and feelings. Only three days decided the fate of her whole future life, hers and his. Having come to Goncharova, having seen many drawings and paintings, the admired Larionov asked her: "Who did all this?" And she answered, "I did!"

Mikhail Larionov and Natalia Goncharova. 1910 photo (fragment)

Natalia Goncharova. "Gardening". 1908

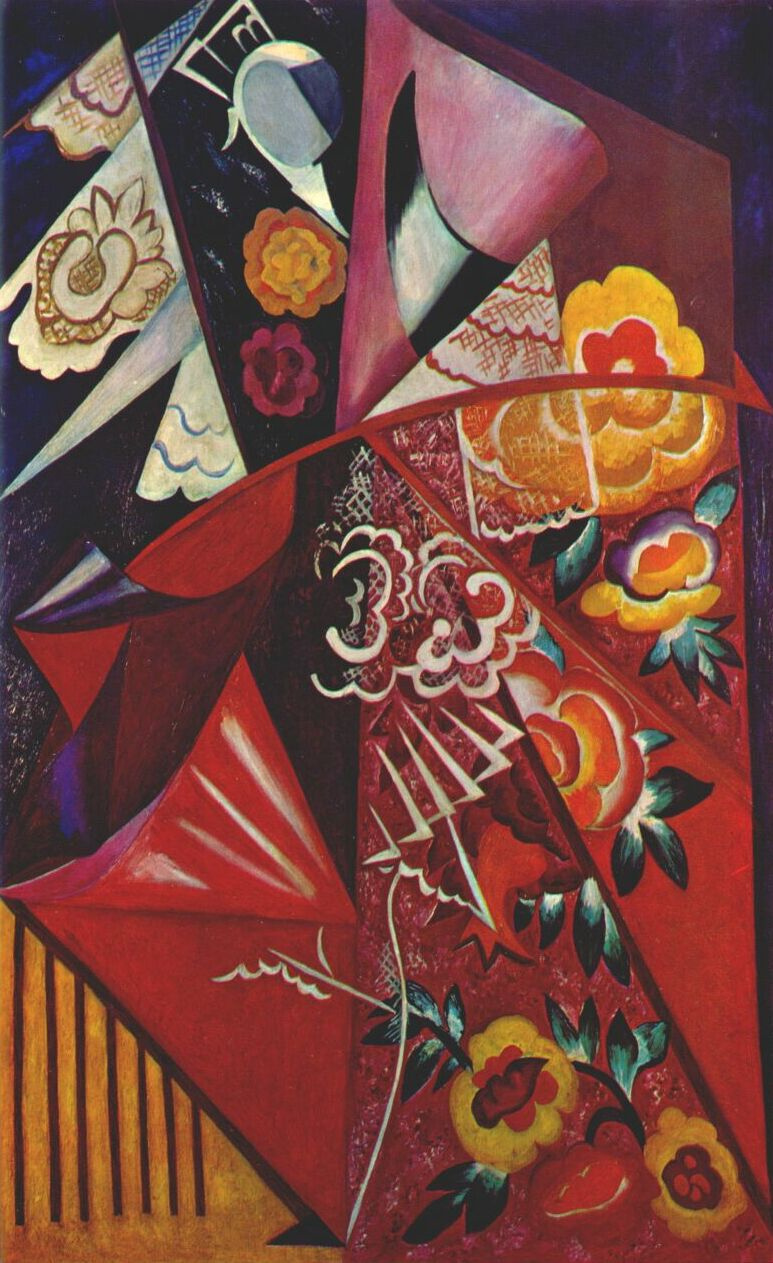

2. Everythingness as a creative worldview

"Everything that was before me is mine," said Goncharova, who did not limit herself to sources of inspiration, work styles and directions. Impressionism , primitivism , cubism , futurism , rayonnism, religious paintings, non-canonical images of saints condemned by the church — "everythingness" (Rus. всёчество)! Rejecting eclecticism, Goncharova declared: "Eclecticism is a blanket of rags, continuous seams. Since there is no seam, it’s mine. The influence of icon? Persian miniatures? Assyria? I’m not blind. I looked at it not in order to forget. "

Natalia Goncharova. "Phoenix" (Polyptych "Harvest"), 1911. Photo © ADAGP, Paris and DACS

3. Scandalous avant-garde nude

Natalia Goncharova could be considered the first Russian avant-garde woman — an unheard combination of concepts in pre-revolutionary Russia. Her first solo exhibition ended in scandal: the artist was arrested, as well as several of her paintings that were declared … "pornographic"!

Natalia Goncharova. "Deity of fertility." 1909−1910 State Tretyakov Gallery

Naked women have been portrayed before, but here, a female artist dared to open woman’s private parts! An unprecedented case hitherto. She didn’t spend much time in prison: Goncharova was acquitted the next day, as the "exhibition was closed" - the formality "hooked" by her lawyer. Note that the exhibition was not positioned as an event open to a wide public, but at the same time, it was held at the Society of Free Aesthetics, one of the most popular cultural venues, which was easy to get to.

Cyclist

1913, 78×105 cm

4. All for success

In 1913, Natalia Goncharova was preparing her major exhibition at the Art Salon on Bolshaya Dmitrovka in Moscow. The artist and her close friends, including Mikhail Larionov and David Burliuk, "warmed up" the audience in every possible way in anticipation of the opening of the exhibition. Larionov showed his epatage, painting on ladies' naked breasts, colourful futurists walked along the city streets … However, it’s not just the surroundings. Sergei Diaghilev perfectly articulated the peculiarity, freshness and originality of what Goncharova did: "If Goncharova simply rouged her cheeks, I would be bored. Goncharova did not just touch up wrinkles; she painted roses."

Natalia Goncharova in futuristic makeup. 1912 photo

5. The hoax biography

Every escapade was naturally picked up by the press, which was just what she required. But this was not enough for the artist: after the opening of the exhibition in the Art Salon, visitors were presented with a truly bewitching biography of the artist. She allegedly was in Paris and worked under the personal guidance of Monet, Renoir, Van Gogh. She was in Tahiti, then studied from Gauguin. She returned to Russia and created religious paintings in one of the monasteries. And then — Madagascar, excavations, sculptures! The audience gasped, though they believed… While all of this was a pure hoax — Goncharova did not leave Russia at that time. The exhibition featured an unprecedentedly large number of paintings — 761 works by Goncharova over 13 years of work. And all the "PR efforts" were not in vain — they enhanced the effect of the exposition and its popularity, and in general, the exhibition changed people’s attitude not only to Natalya Goncharova, but also to the avant-garde . The Tretyakov Gallery acquired several her paintings — an undoubted success.

Apple picking

1909

6. The Golden Cockerel and 51 telegrams

Mikhail Fokin, Sergey Diaghilev and Alexander Benois came to Moscow to meet the art of Goncharova and Larionov. It was Benois who suggested that Diaghilev consider Natalia Goncharova as the designer for his The Golden Cockerel ballet. And this meeting was a turning point in the fate of the artists' family. In 1915, Sergey Diaghilev sent 50 telegrams to Natalia Goncharova with cooperation proposals, and was refused. Finally, in the 51st one, he finally invited her and Larionov. And they went — forever, although they did not suspect it.

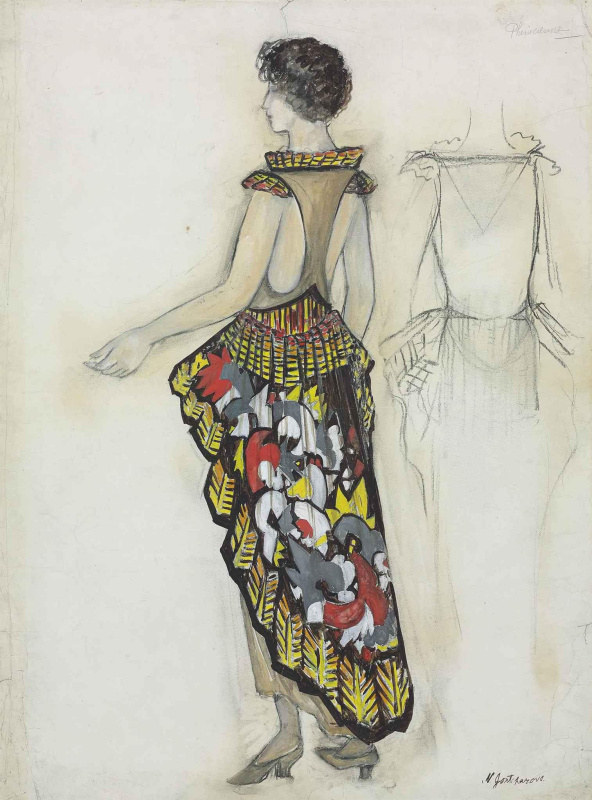

Natalia Goncharova. Design of a peasant woman costume for the "The Golden Cockerel" opera-ballet, 1937

Photo © ADAGP, Paris and DACS, for theguardian.com

Photo © ADAGP, Paris and DACS, for theguardian.com

Diaghilev did not fail: the artists worked together on the scenery, personally painted them. Costumes were delightful, and Parisian fashionistas repeated patterns in their outfits. "Russian Seasons" were the great success again. Brightness, sincerity, not imitation, not a la russe — but authenticity, the subtle sense of detail. The Golden Cockerel was an event, and the Goncharova’s scenery opened a new chapter in decorative art.

7. Fashion trendsetter

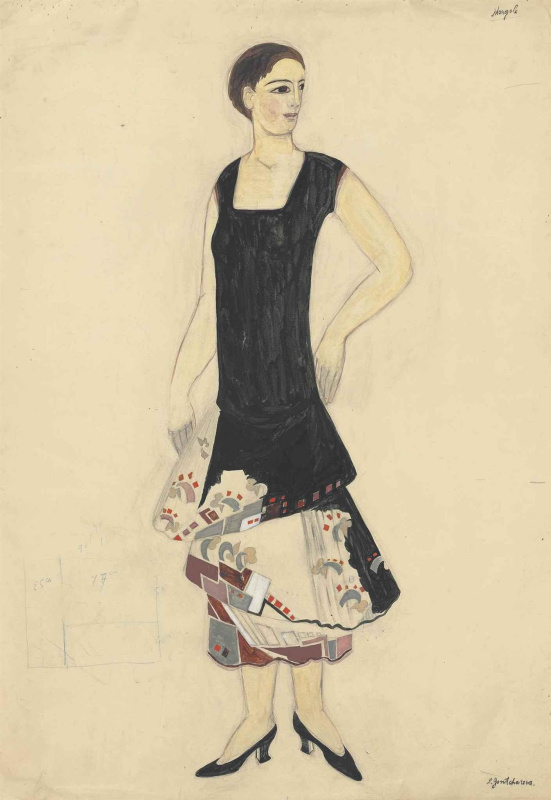

The cousin’s great-granddaughter of the captivating Natalia Pushkina, Goncharova did not shine at the balls, but she proved herself in fashion. It was her hand that the Russian ladies put on shirt dresses, and Goncharova was one of the first to wear trousers and caps, challenging society. In Moscow, Natalia Goncharova made sketches for the Russian Fashion House of Nadezhda Lamanova. After leaving for Europe, in 1924, Natalia collaborated with the then-famous Myrbor fashion house headed by Maria Cuttoli, the wife of French senator. The artist created a series of sketches for Myrbor, such celebrities as Pablo Picasso and Fernand Leger assisted her working on the collections.

Natalia Goncharova. Sketch

of textile design for the Myrbor fashion house, 1925−1928

Photo © ADAGP, Paris and DACS, for theguardian.com

Photo © ADAGP, Paris and DACS, for theguardian.com

Goncharova also worked with the Chanel Fashion House, and the sketches of the outfits she created were published by Vanity Fair and Vogue magazines.

8. Poems that Marina Tsvetaeva did not know about

Marina Tsvetaeva and Natalia Goncharova met in the summer of 1928 in Paris. Their first meeting was scheduled in the cafe "Le Petit Saint-Benoit" where poets, artists, and journalists often gathered. The meeting and subsequent communication resulted in the "Natalia Goncharova" essay by the admired Tsvetaeva, in which the two fates of two Natalia Goncharovas, the artist and her great-great-grandmother, Alexander Pushkin’s wife, were intertwined. The essay was first published in the Prague magazine Volia Rossii in 1929. However, Tsvetaeva could not even imagine that Natalia Goncharova wrote… poetry. "Take Goncharova — she’s never written poetry, she’s never lived poetry, but she understands because she looks and she sees…" said Tsvetaeva. While there were poems. Natalia versified in both Russian and French. Four notebooks with poetry were discovered in the archives of the Tretyakov Gallery by art critic Olga Furman and first published in the Nashe Nasledie (Our Heritage) magazine in 2014. Here is one of them:I carry what the

Lord gave me.

I knocked at all the doors

I prayed under the windows

And cried out in all the squares:

I carry the gift of the Lord within me

I carry the wind of spring with me

I carry summer thunderstorms

I carry with me the late autumn’s

Golden foliage

And blizzards, and winter’s hoarfrost.

Yet shutters and doors are closed,

Your ears cannot hear,

Eyes cannot see.

Frost shimmers in my hair.

The centuries will tell you

That you are destitute, scorned.

You have neglected God’s gift.

Flowers

1912, 72.7×93 cm

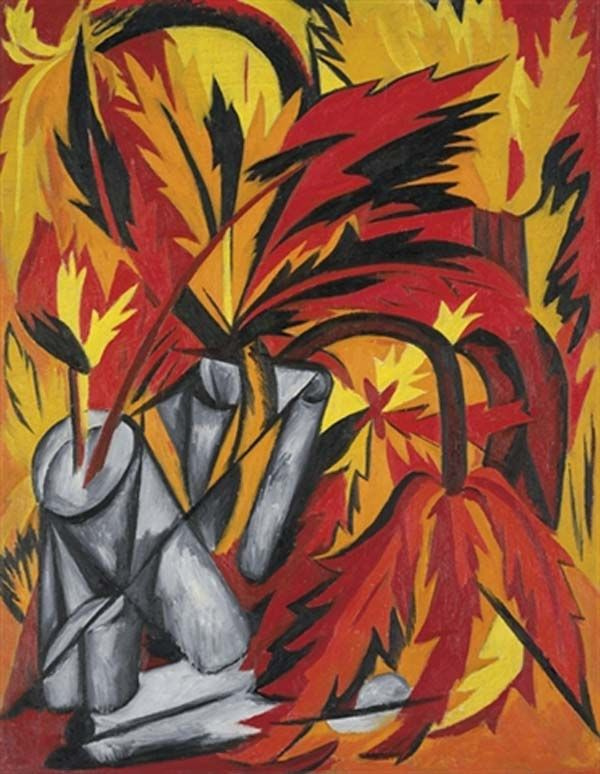

9. Goncharova and the record “rayonnism”

The "rayonnist" paintings by Natalia Goncharova were born from the source of the creative and loving union with Mikhail Larionov, who came up with a new direction — "rayonnism", which became the forerunner of Russian abstract art. The formal duration of rayonnism was short: after Larionov’s "Glass" shown in 1909, the rayonnist paintings were only presented in 1913, at the Target exhibition by the Donkey’s Tail society. Natalia Goncharova and Mikhail Larionov, Mikhail Le-Dantu and Kazimir Malevich, Marc Chagall and Oleksandr Shevchenko showed their work. Many years later, in 2008, the rays from the "Flowers" still life by Natalia Goncharova turned into her rays of glory. In London, at Christie’s auction, the painting was sold for $ 10.9 million, making Goncharova the most expensive Russian artist — the record has not been broken till now.Also read

Rayonism

In February 2010 at the Christie’s auction in London, the "Spanish Woman" by Natalia Goncharova (1916) was sold for US $ 10,216,148

10. Pictures and close relationship

"Larionov and I have been together since the day we met," said Natalia Goncharova. Larionov was very proud of her success and was much more serious about it than about his own career. Their lives were united by something more than love. What was it — vocation, art, emotional closeness? Whatever you call it, the fact remains: even when Larionov got his Shurochka (Alexandra Tomilina, Larionov’s mistress for 30 years, and his second wife after the death of Natalia Goncharova), and Natalia Goncharova met her Orest Rosenfeld (emigrant from Russia, French socialist), all this did not violate the harmony that prevailed between them. Only in 1955, Natalia Goncharova married Larionov — so that the paintings, in the event of the death of one of them, remained in the family.

Natalia Goncharova. Polyptych "Harvest" (fragment). 1911. © ADAGP, Paris and DACS

Оn a final note, let’s mention the scale of the recent show in Tate Modern. More than 160 works by Natalia Goncharova were provided by the Tretyakov Gallery and the Russian Museum, as well as a number of other collections and private collections.

The exposition touched on almost all of the innovative areas, in which the artist worked — futuristic body art and monumental religious painting, avant-garde

cinema and book graphics, performance design and artwork for fashion houses in Moscow and Paris.