Modernism is more than an art movement. It is a whole complex of changes and processes that took place in culture, art, literature, architecture in the second half of the 19th — the first half of the 20th century. Among the main historical premises of this revolution in art were city development, industrialization and two world wars — processes and events that affected the whole world.

Where and when

The chronological framework of modernism is most often quite definite and varies slightly from one research to another: some insist that irreversible changes have already begun with the realism of Gustave Courbet, others count down from the Salon des Refusés, which took place in 1863 and hosted Édouard Manet's "The Luncheon on the grass". Be that as it may, all of them agree that modernism began in France.When they talk about modernism or modern art, they always mean a lot of artistic movements and styles, associations and directions, which often existed simultaneously and turned out to be opponents in many ways. At first glance, it is difficult to find common features in the art of surrealists and expressionists, cubists and constructivists. But from French impressionism and to American abstract expressionism, artists stepped into the coordinate system, the search area that sharply separated them from all previous generations. With the beginning of modernism, the era of the fine traditions of the Renaissance ended.

Key moments

1. There is a controversial, but reasonably good reason to consider the beginning of the modernism precisely with the realism of Gustave Courbet. Until he began to paint peasant women with dirty heels, the set of motifs and subjects worthy of high art hardly expanded significantly since Raphael. Biblical events, ancient mythology, heroic battle scenes, pastoral or dramatic landscapes, all these subjects could certainly count on being exposed at the Paris Salon, and their creators — on the well-fed life of a salon artist. 350 years of methodical service to the ideals of Raphael led to the fact that from year to year, the salon walls contained more Venuses and Roman patricians than images of modern life. And only Courbet showed his impudence to paint nudity on a scandalously large canvas, without endowing it with a divine name.

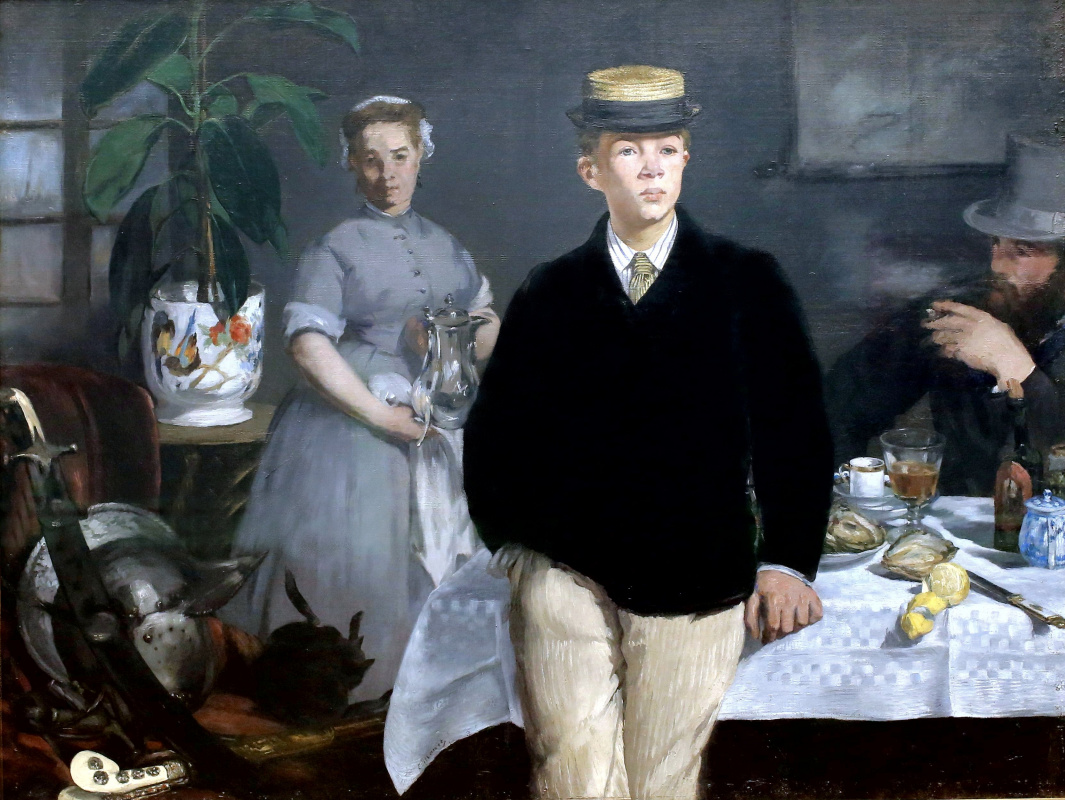

Luncheon in the Studio

1868, 118×153 cm

2. Though, Édouard Manet surely became the most obvious and much bolder prophet of modern art. Not only did he involuntarily lead a group of artists who would later be called impressionists, he laid the foundations for a new perception of painting. He shifted the focus from the content of the picture to the methods and process of the painting: form, line, colour, intentionally distorted perspective. He was the first to be criticised for his painted products on the table nearby, not because they are combined for a specific meal, but because their colours are in perfect harmony.

3. Moreover, Manet made his viewer worried, who felt quite comfortable until then as the centre of interaction with the picture. He, the viewer, used to be the main one, and from his confident look built the artist the right perspective, not causing dizziness or laughter. Manet played with the viewer: in Olympia, the viewer felt like a client in front of the prostitute’s bed, in The Execution of Emperor Maximilian, he is the indifferent observer, whose shadow casts in the foreground of the picture, and in A Bar at the Folies-Bergère, he is the visitor in front of the counter. Cézanne would go even further, he’d paint still lifes as if he was looking at them from several points of view at once. Cubists would push this painting method to the limit, and the unconditional position of the always right viewer will thoroughly shake.

3. Moreover, Manet made his viewer worried, who felt quite comfortable until then as the centre of interaction with the picture. He, the viewer, used to be the main one, and from his confident look built the artist the right perspective, not causing dizziness or laughter. Manet played with the viewer: in Olympia, the viewer felt like a client in front of the prostitute’s bed, in The Execution of Emperor Maximilian, he is the indifferent observer, whose shadow casts in the foreground of the picture, and in A Bar at the Folies-Bergère, he is the visitor in front of the counter. Cézanne would go even further, he’d paint still lifes as if he was looking at them from several points of view at once. Cubists would push this painting method to the limit, and the unconditional position of the always right viewer will thoroughly shake.

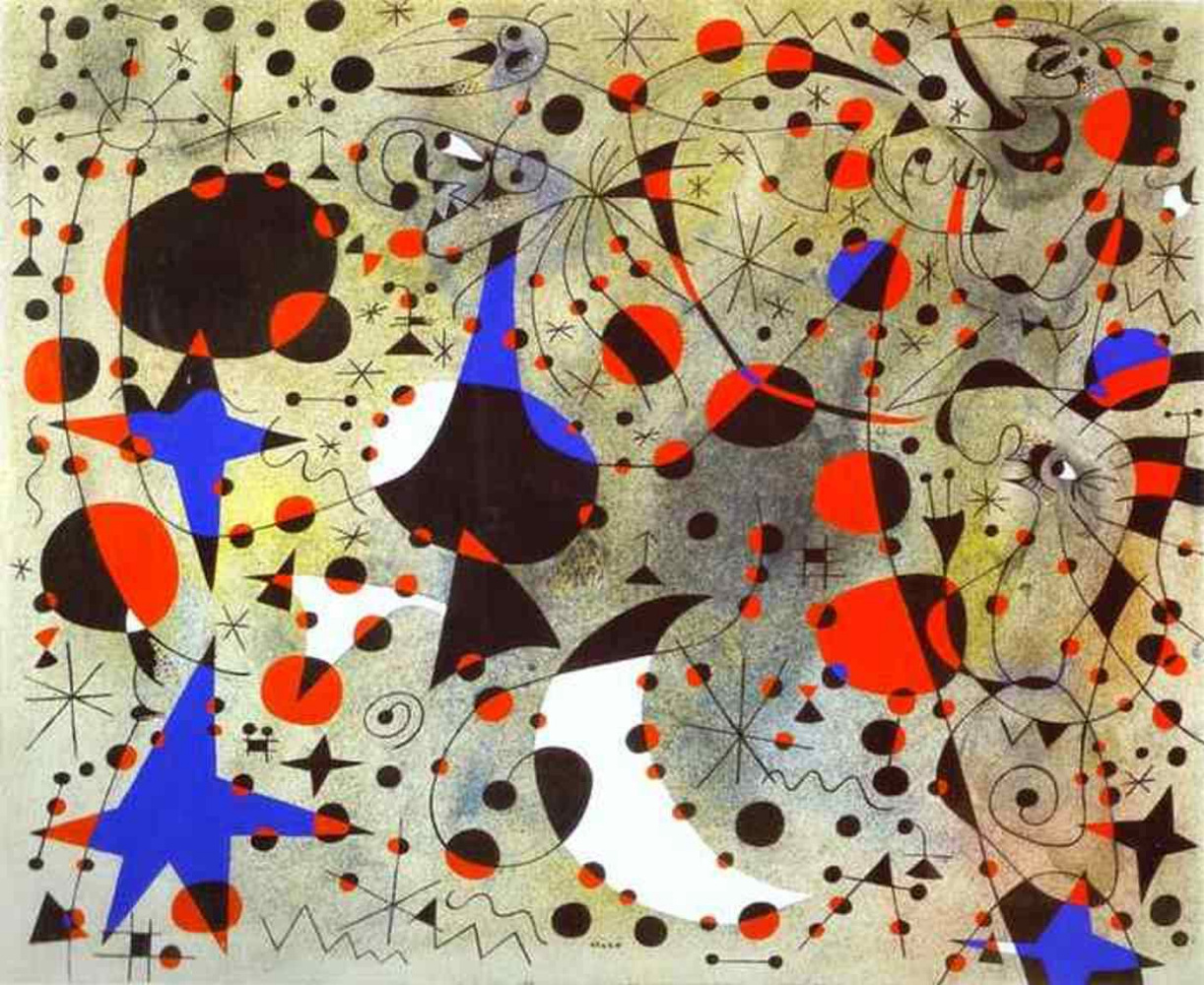

4. Despite the hard conflicts and the dissimilarity of the art movements, which are usually referred to as modernism, each of them is characterized by the common features: the experiments and finds in the field of form, colour, and technology. From Manet to abstract expressionists, all modern artists are more focused on painting and material rather than on a subject. From impressionist separate brushstrokes, violet shades and Seurat's divisionism to pure abstraction of Kandinsky, Suprematist compositions by Malevich, and colourfield painting by Rothko. Painting has its own pictorial value, which is not related to the value of the depicted subject. Renoir said: "The most important thing in our movement, I think, is that we freed the painting from the subjects. I am free to paint flowers and simply call them "flowers", without having their own story."

In his famous article "Vanguard and Kitsch", which was published in 1939, American critic and art theorist Clement Greenberg wrote:

"Picasso, Braque, Mondrian, Kandinsky, Brancusi, even Klee, Matisse and Cézanne draw their inspiration mainly from their own expressive means. The impulse of their art, apparently, lies mainly in its preoccupation with pure invention and the organization of spaces, surfaces, shapes, colours, etc., till the exclusion of everything that is not properly contained in these factors."

"Picasso, Braque, Mondrian, Kandinsky, Brancusi, even Klee, Matisse and Cézanne draw their inspiration mainly from their own expressive means. The impulse of their art, apparently, lies mainly in its preoccupation with pure invention and the organization of spaces, surfaces, shapes, colours, etc., till the exclusion of everything that is not properly contained in these factors."

5. And yet, the part of the art movements that held on to figurative painting, without going into abstraction with all their passion for experimentation legalized many subjects in art that had earlier been forbidden and unworthy of the sacred galleries. These were the Impressionists, the Fauvists, the Nabis

, the Expressionists, and the London School. In city landscapes, for example, railway bridges, engineering structures and even repair work began to appear. Moreover, the landscape

has become a full-fledged genre; for some pond in a quiet corner of the garden, artist now takes a huge canvas, previously only allowed for historical or mythological painting. But one of the most important changes has occurred in the image of a nude female nature. "In this respect, as in many others," writes John Berger in The Art of Seeing, "Manet was a turning figure. If you compare his Olympia with the original by Titian, you will see a woman playing a traditional role, but playing it with a certain challenge." And then — Degas's bathing women, endless images of nudes in the bathroom in the Bonnard's series, prostitutes by Toulouse-Lautrec and Picasso. Woman ceased to be a seductive object of contemplation, whose gaze is always directed towards the male spectator.

Bauhaus building

1926

Modernism in architecture

Each new art movement in painting faced with constant resistance and rejection of critics and spectators, but in architecture, the turn to modernism was urgent, almost vital. The fast-growing cities and the industrial revolution required new solutions: low-cost housing for new urban residents, functional factory buildings and industrial offices, the need to rebuild entire neighbourhoods after two devastating world wars.The architects of the new era, first of all, refused to decorate buildings and national elements — architecture became universal and functional from Latin America to Japan. The form of construction no longer followed any tradition, the focus shifted to the building function and materials. Of course, those were not stone and wood, but the revolutionary materials like concrete, metal and glass.

The main vector of the modernist architecture movement took its shape at the beginning of the twentieth century, and the most accurate formulation was received from the inventor of metal and glass skyscrapers, architect Mies van der Rohe: "Less Is More".

New materials made it possible to achieve previously unimaginable height of buildings, to experiment with the layout, to glaze huge façade fragments and even the entire wall. Bearing concrete pillars made it possible to experiment with the shape of the walls as much as necessary, to achieve the sculptural shape of the building: it could resemble a balloon or a shell floating in the air, imitate the shape of open palms or an undecorated Gothic cathedral.

New materials made it possible to achieve previously unimaginable height of buildings, to experiment with the layout, to glaze huge façade fragments and even the entire wall. Bearing concrete pillars made it possible to experiment with the shape of the walls as much as necessary, to achieve the sculptural shape of the building: it could resemble a balloon or a shell floating in the air, imitate the shape of open palms or an undecorated Gothic cathedral.

Modernism includes the German Bauhaus, as well as Soviet constructivism

, world-spread international style, and brutalism. Despite the fact that 1960s—1970s are considered the date of the official end of modernism in architecture, it never lost its relevance. At least because most urban residents work and live today in buildings built by modernists. Rather, after buildings and even entire cities built by Walter Gropius, Le Corbusier, Mies van der Rohe, modernism exhausted possible ideas and forms, received a perfect embodiment and at the same time reached its limit of development.