Botanical Illustration is a unique genre of art. It combines seemingly incompatible qualities: scientific accuracy on the one hand and artistic accomplishment — on the other. In exceptional cases, botanical artists managed to convey in their images the striking delight of the discoverer and the astonishment caused by the beauty and perfection of an orchid that blooms once in 15 years or a South American flowering shrub that had yet to be named.

At a time when the world was young and full of mysteries. At a time when great commanders took scientists and artists to their invasive military campaigns so that they explored the conquered lands. At a time when scientific discoveries required physical endurance, tremendous courage and a natural propensity for adventure. In the world without photography, trains, planes and bathyscaphes, a naturalist had to have at least basic drawing skills — in order, if necessary, to fix the first-encountered, unknown moss, a butterfly, or plankton. A scientist, setting out for an overseas expedition or working at the Royal Botanical Gardens, had not only a pair of tweezers, a magnifying glass, a scalpel and an album for a herbarium, but also watercolors.

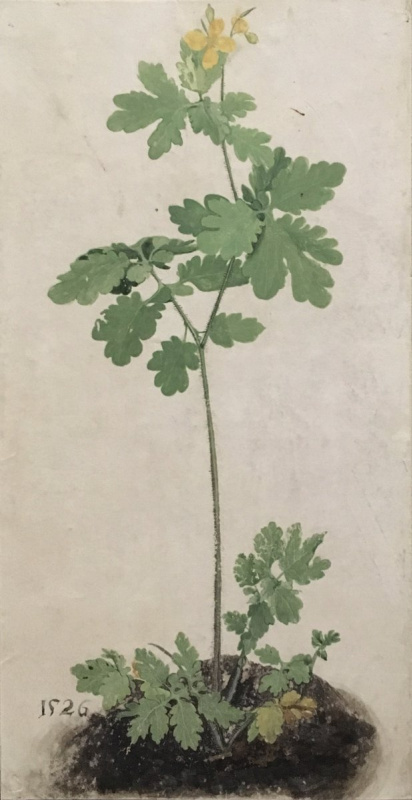

Flower catchment

1526

Pharmaceuticals, science and realism

Until the 16th century, Europeans had only one book about the properties of medicinal plants. It was written in about the year 77 C.E. by a Greek army physician Dioscorides and contained illustrations made from nature. The book De Materia Medica (On Medical Material) was so meticulously and thoroughly compiled by a herbalist that for fifteen hundred years it was copied, redrawn, supplemented with poetic inserts and comments in different languages; pharmacists found it useful while distinguishing a Chinese plantain from a muscari, finding a snake venom antidote or curing fever.With the beginning of the Renaissance , Dioscorides’s book didn’t lose its relevance (many famous botanists would rely on it for several centuries), but the world around was drastically changing: Gutenberg invented the printing press, new continents and islands appeared on the world map, and on them — completely different vegetation, food, bark and herbs, which unexpectedly turned out to be a panacea for European diseases. Finally, the Earth began to revolve around the Sun, not vice versa, and the world began to revolve around people. And they felt freedom in cognition of the world around them and responsibility for exploring it.

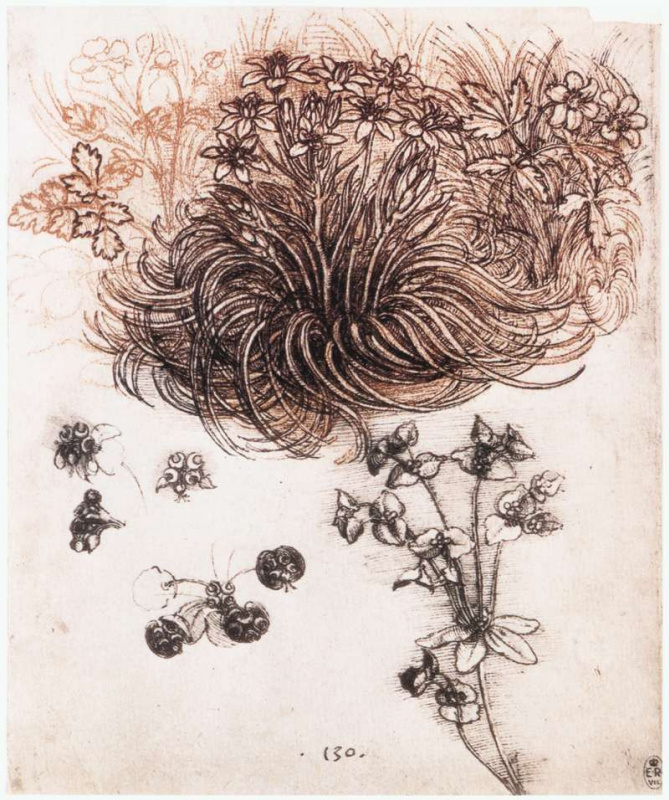

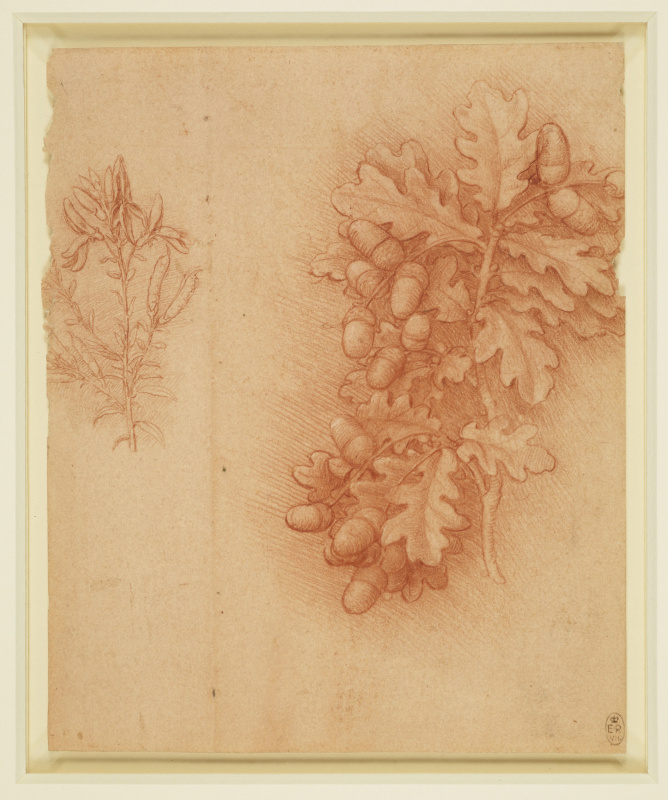

The first authors of botanical illustrations were artists. For them, the accuracy of the depiction of flowers and trees became as important as the observance of human body proportions and knowledge of anatomy. Almost every second page of Leonardo da Vinci and Albrecht Dürer's albums contained botanical sketches. Just as medieval healers knew by heart the names of herbs and consulted Dioscorides’s book while making medicines from them (by the way, the illustrations were already pretty deformed and lost resemblance to real plants as a result of endless copying) — so the Renaissance

artists made their own herbals in an effort to follow reality. For the first time it was done for the purpose of cognition, studying laws and conformity of forms, and not to find the right prescription for treatment.

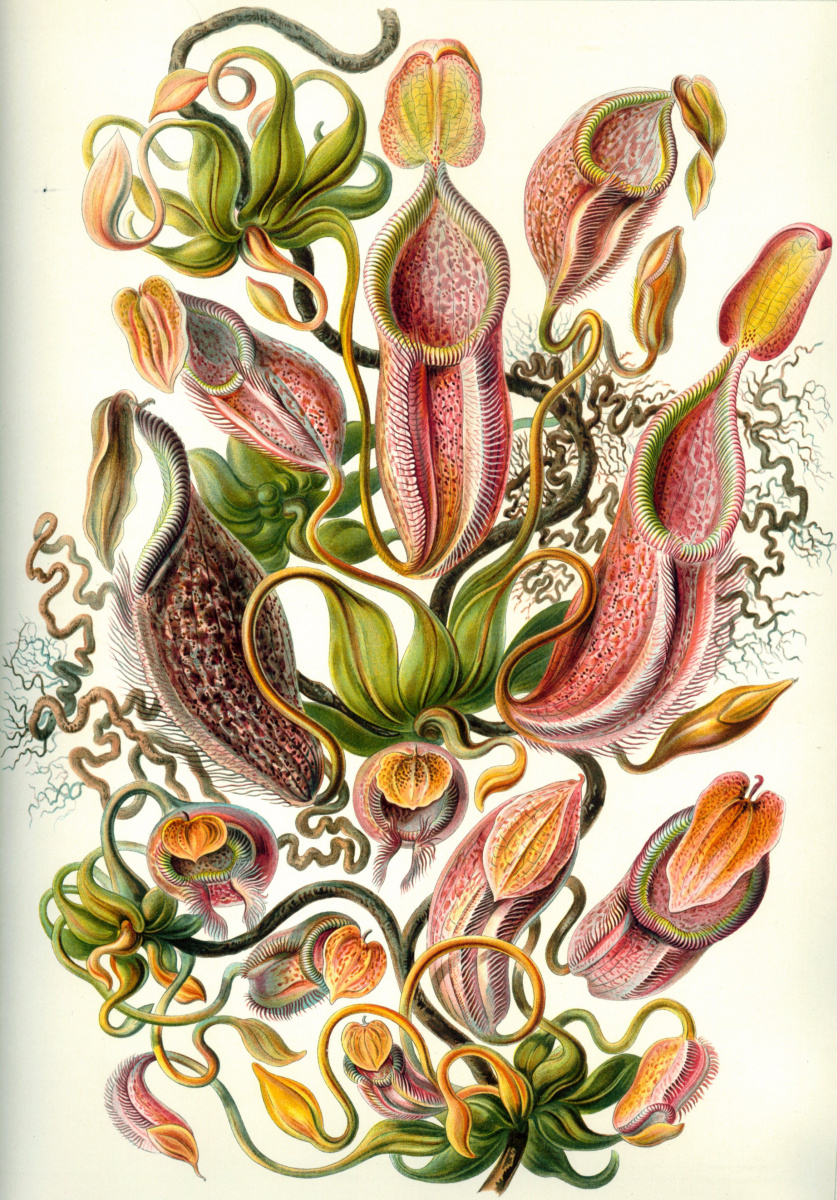

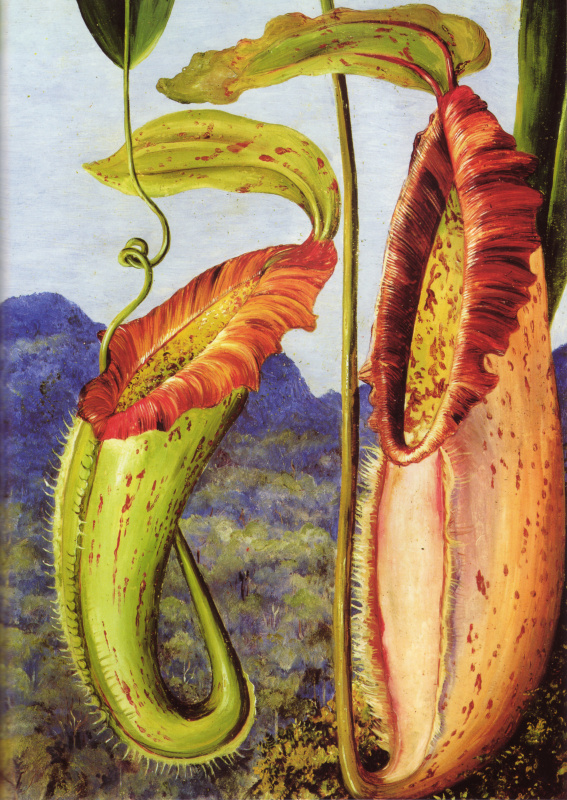

Nepentes (jugs). "The beauty of form in nature"

1904, 32×24.5 cm

Ships and microscopes

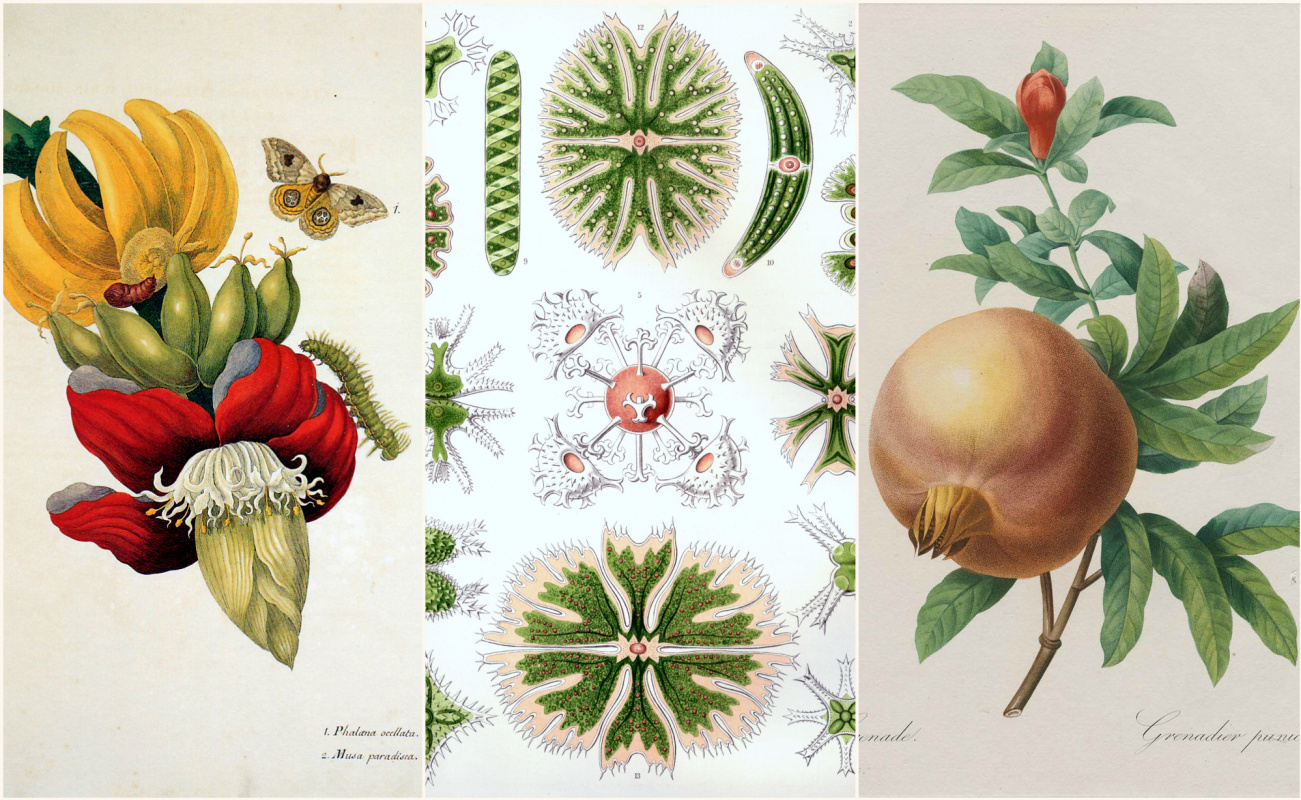

The next generation of authors of botanical illustration was no longer pharmacists or realist artists. It was a generation of scientists. Those who went to exotic countries, spent years in tropical rainforests, got wet in the rain, suffered from seasickness, returned home with priceless seeds, carefully wrapped in moss or dry sand, and with drawings of plants, insects and birds never seen before. Or those who took care for the overgrown Royal Botanical Gardens with their greenhouses, rare species of sensitive plants and vain plans to surpass the Botanical collection of the neighboring monarch. Some of them managed to look so closely and intently at the divine plan, in accordance with which all life in the world was organized, that their watercolor sketches and hand-painted engravings became an endless inspiration for many generations of artists.Maria Sibylla Merian, for example, spent a month travelling all the way across the Atlantic Ocean and then lived in Suriname for two years. The forest there grew together so closely with thistles and thorns, that she often sent slaves, so that they chopped an opening for her. Merian studied insects of Suriname and stages of their transformation from caterpillars into butterflies with iridescent wings or disgusting cockroaches, which her pious European compatriots called "beasts of the devil". At that time, she was already 52 years old — and she managed to learn painting and engraving

in the studio of her father and stepfather, get married, escape from her husband with their children, become a successful independent entrepreneur and an author of several books about flowers. By the way, it was in the 17th century, and not every male scientist would dare to do what she did in the name of science. And Merian, of course, did not have the opportunity to get an education and got art materials only from her male relatives who could afford buying them.

She painted each beetle, butterfly, lizard or caterpillar in watercolors in their habitat — on amazing exotic flowers.

She painted each beetle, butterfly, lizard or caterpillar in watercolors in their habitat — on amazing exotic flowers.

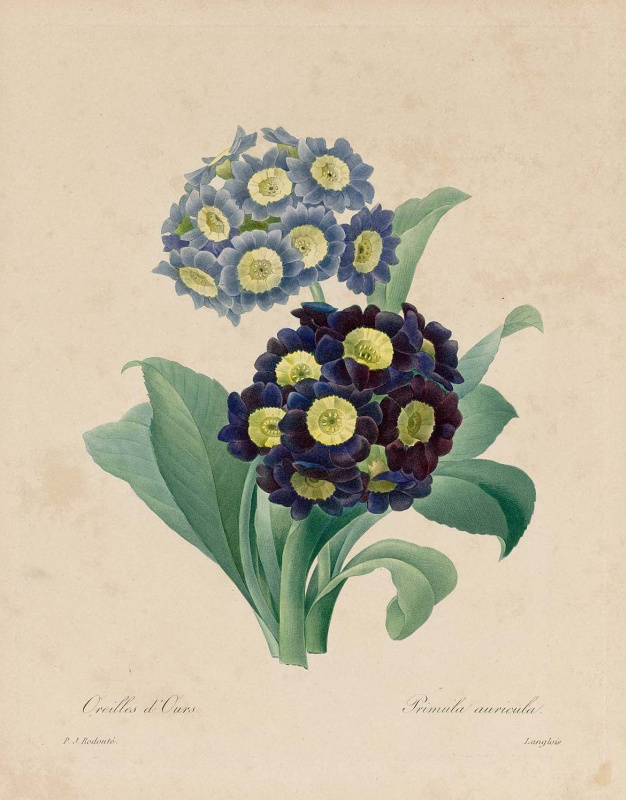

Pierre-Joseph Redouté dissected and studied the plants in the Royal Botanical Gardens, and at the same time painted flowers collected there. Botany is an area that doesn’t change due to the change of political regimes. Botanists didn’t get executed along with kings and other courtiers. It was possible to study roses and lilies both under the monarch and under the emperor Napoleon. Therefore, Redouté easily got through the change of power. Being a royal botanical artist, he painted floral still-lifes first for Marie Antoinette and later — for Josephine Bonaparte.

Ernst Haeckel was a German scientist who trained as a physician before toying with the idea of becoming a scientist — or a landscape painter. Fortunately, he became a naturalist, and spent life using his microscope to study plankton, jellyfish and cnidarians. As a result, he discovered 120 new species of radiolaria and published books that still inspire artists and designers all around the world. He visited the coasts of Sicily, Egypt, Algeria, Italy, Madeira and Tenerife. Haeckel died in 1919 — and got a chance to experience an era in art, when albums of engravings published by him inspired artists for semi-abstract experiments and even architects who wanted to design buildings which would resemble jellyfish discovered by the biologist.

Ernst Haeckel’s book Art Forms in Nature was published at the turn of the century in ten sets of ten plates. Each page was organized so that the complex symmetry of each species participated in the overall compositional perfection.

Ernst Haeckel’s book Art Forms in Nature was published at the turn of the century in ten sets of ten plates. Each page was organized so that the complex symmetry of each species participated in the overall compositional perfection.

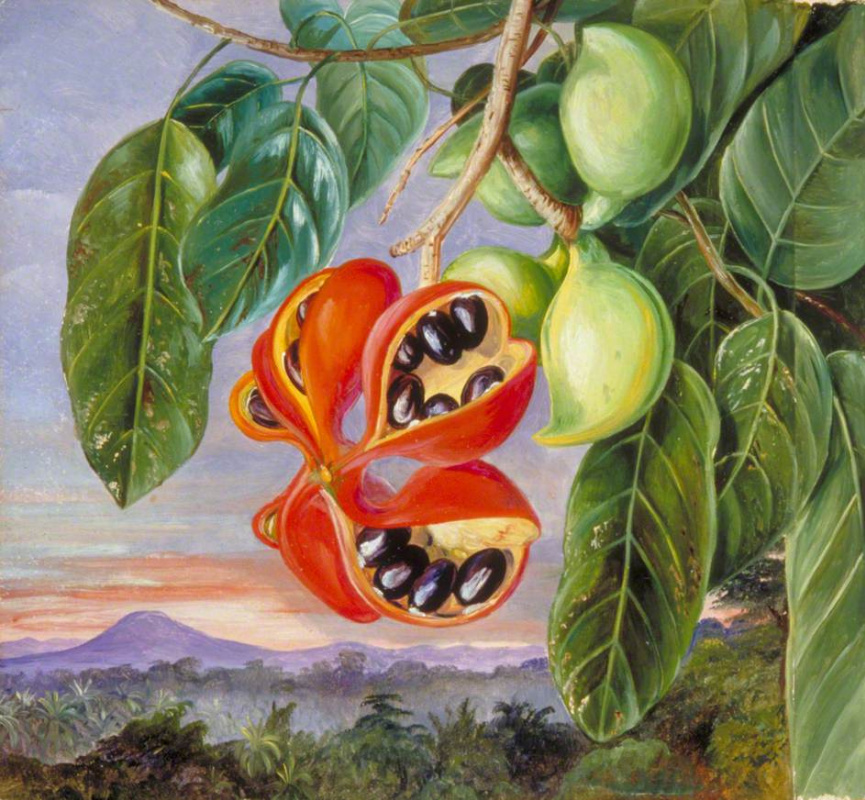

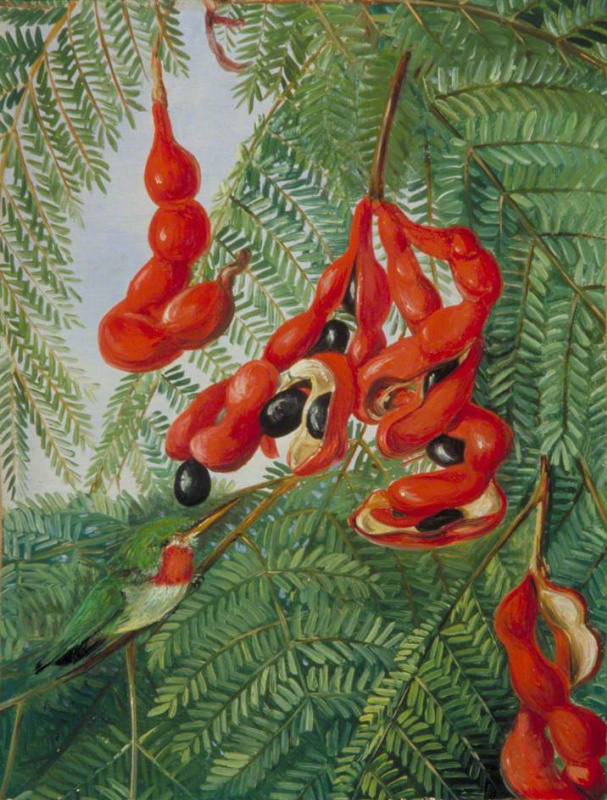

Marianne North was a British artist, an explorer who traveled alone and never brought any wooden boxes to collect seeds from exotic plants. 13 years in a row, she took only a set of oil paints on her trips around the world. The daughter of a wealthy landowner, she didn’t have any desire to get married, calling it a "terrible experiment" that made women into "a sort of upper servant." Unlike the majority of professional botanists, North painted plants in their habitat: large exotic flowers set against a unique landscape

. Such a contemplative and pictorial method of research did not prevent North from discovering several unknown plant species, including the largest known carnivorous pitcher plant, which was named after her — Nepenthes northiana. Going to remote places on foot, North would settle in a forest hut and paint.

The explorer and artist North had no formal training in illustration — she just took a few drawing lessons. And yet, the exhibition of her work in London in 1879 was an immense success. Amazed by huge public and press attention, North decided to donate her entire collection to the Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew. She built a gallery at her own expense and hoped that the visitors would be served tea or coffee and biscuits. The director of Kew Gardens gladly accepted the project of the new gallery, but turned down the suggestion that tea had to be provided there. After all, it was a place of work for serious scientists, not a tourist attraction.

Illustrations by Marianne North are pictorial documents of bygone places. In less than a few decades, many of them were crushed by the ruthless signs of civilization: roads, shops, postal stations and offices.

These famous artists, authors of botanical illustrations, and hundreds of others formed a unique artistic aesthetics based on scientific accuracy and close attention to the smallest detail. It is not surprising that very soon this aesthetics would be picked up by new, avant-garde artistic trends and styles.

The explorer and artist North had no formal training in illustration — she just took a few drawing lessons. And yet, the exhibition of her work in London in 1879 was an immense success. Amazed by huge public and press attention, North decided to donate her entire collection to the Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew. She built a gallery at her own expense and hoped that the visitors would be served tea or coffee and biscuits. The director of Kew Gardens gladly accepted the project of the new gallery, but turned down the suggestion that tea had to be provided there. After all, it was a place of work for serious scientists, not a tourist attraction.

Illustrations by Marianne North are pictorial documents of bygone places. In less than a few decades, many of them were crushed by the ruthless signs of civilization: roads, shops, postal stations and offices.

These famous artists, authors of botanical illustrations, and hundreds of others formed a unique artistic aesthetics based on scientific accuracy and close attention to the smallest detail. It is not surprising that very soon this aesthetics would be picked up by new, avant-garde artistic trends and styles.

Study of rocks and ferns

1843, 29.4×40.6 cm

Running back to Dürer and da Vinci

In the second half of the 19th century, French painting was undergoing a huge revolution — first the Barbizon-school painters, and then the future Impressionists turned to plein air painting and recorded their impression of the surrounding landscape and lighting effects. If the straws in the stack are hardly seen — there is no need to paint them in detail, if the grove hides behind the fog — only subdued dots are visible, not millions of individual leaves. But this is only the central, but not the only way of the development of art. At the same time, a French symbolist painter Odilon Redon produced collections of lithographs with bizarre plants with sad human heads swaying on long stems. And perhaps he did not follow the Impressionists' footsteps because his main teacher was Armand Clavaud — a botanist and an assistant director at the botanical gardens in Bordeaux.Clavaud was working on his own theory about intrinsic links between plant and animal organisms. But besides this theory, which obviously influenced Redon, the assistant director at the botanical gardens Armand Clavaud shared with the young artist voluminous herbariums and his own botanical illustrations, new books and ideas about art. Somewhere there, in the office of the famous botanist, Redon developed his own artistic principle: carefully studying nature, the structure of the smallest living organisms, so that later, in his studio, he could create chimeras and ghosts according to the discovered laws of nature. It wasn’t enough to come up with a plant with a human head instead of the flower; he had to let the viewer feel how water moved along the stem from the roots, penetrating the creature’s complex circulatory system.

During the grandiose scientific discoveries in the field of natural history, Charles Darwin’s homeland wasn’t about Impressionism

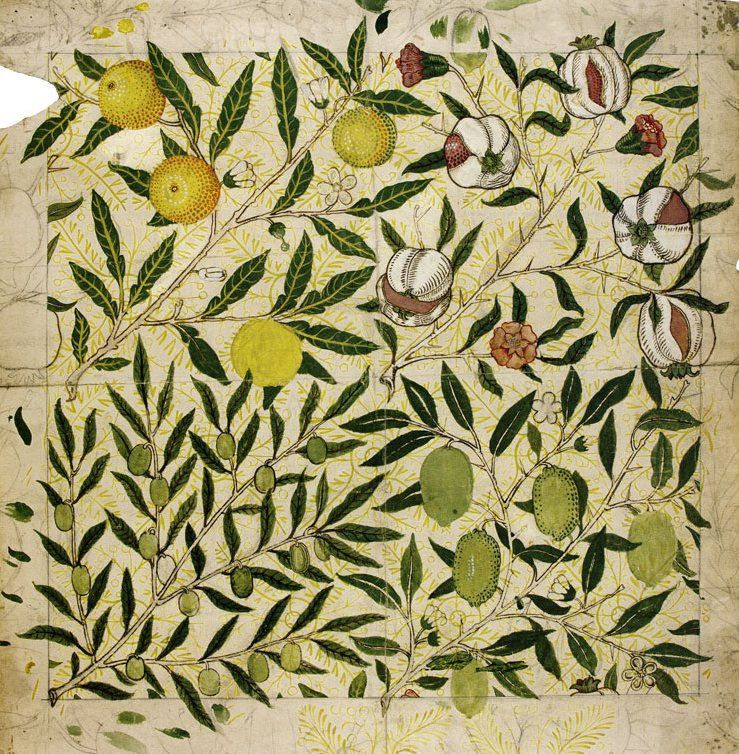

either. In the UK, the most influential art critic was John Ruskin, a writer and artist who created botanical and geological sketches while travelling and advocated following nature as closely as possible. The Pre-Raphaelites

, who were inspired by Ruskin’s ideas, worked directly from nature when painting people or nature. But unlike the Impressionists, counting the number of leaves and berries on each shrub — they didn’t find it that difficult. When Millais was painting his Ophelia, the model had to lie for hours in a bath, and to paint flowers properly, the artist made sketches from nature. Female characters in the paintings of pre-Raphaelites are often surrounded by flowers, and it’s not difficult to determine the type of a particular plant and its main botanical characteristics. The artists believed that following the nature in the smallest detail was the only way they could bring British art out of the swamp, in which it was mired. Quite soon, by the end of the 19th century, seeds sown by pre-Raphaelites would have thin, curved stems, intricately intertwined in decorative patterns. In the Art Nouveau era.

Postbotany, paper and glass

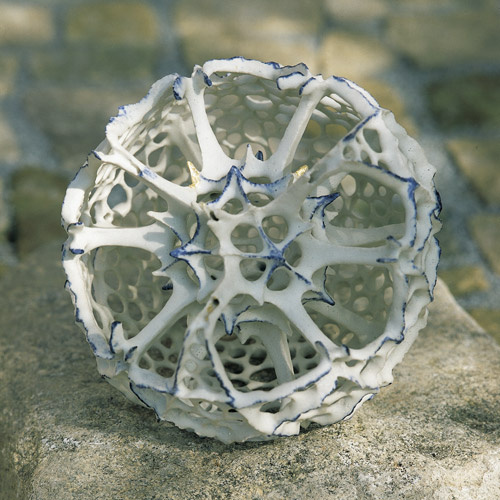

In the 20th century, anyone could use a ship or a train to travel the world, looking for happiness and wealth in distant, homeless lands. All continents had already been discovered, there were fewer and fewer unexplored places in the world. The once-wild forests were well-trodden, trails had been laid, the aborigines put on European clothes, were baptized and learned to speak English. Botanical atlases had already been created, different classifications of plants — invented, unseen birds and insects — studied. The artist’s task was to take over the spheres of influence, which the industrial revolution couldn’t reach, to disseminate exotic creatures and plants directly to the homes of tired Europeans. Artists and sculptors of the Art Nouveau era chose floral motifs and smooth lines, imitated the faded colors of old elegant botanical illustrations, painted with watercolours, and added gold to them. Their art was no longer limited to the halls of galleries — it penetrated into private houses in the form of floor lamps, wallpaper, panels and fancy furniture.On the other hand, artists who were fighting for new abstract art, devoid of subject matter, would still be amazed at the republished books of Ernst Haeckel, finding inspiration and pure perfection in the weird intertwining of radiolaria’s skeleton. Paul Klee and Wassily Kandinsky admitted being hugely influenced by Art Forms in Nature. Klee dreamt of growing a painting the way flowers are grown. Architect Hendrik Petrus Berlage designed buildings in the form of a jellyfish illustrated in Haeckel’s book. The endless variations of flowers by Georgia O’Keeffe (1, 2, 3) are very similar to oil sketches by Marianne North.

Works by contemporary artists Kate Kato, Rogan Brown, Leopold and Rudolf Blaschka, Gerhard Lutz. Photo sources: www.kasasagidesign.com, roganbrown.com, www.flickr.com, www. lutz-tonkunst.de

The influence of the most brilliant scientific illustrations on art has never stopped — even today young artists, impressed by the books of natural scientists who lived 300 years ago, create sculptures of metal, ceramics, glass and paper. Longing for a world that was still young and full of mysteries, the thirst for discoveries and new knowledge made them search for unexpected techniques and meanings.

Author: Anna Sidelnikova

Cover illustration: Maria Sibylla Merian, Banana Flower and Fruit; Ernst Heinrich Haeckel, Siphoneae: desmids; Pierre-Joseph Redouté, Pomegranate.

Author: Anna Sidelnikova

Cover illustration: Maria Sibylla Merian, Banana Flower and Fruit; Ernst Heinrich Haeckel, Siphoneae: desmids; Pierre-Joseph Redouté, Pomegranate.