The Renaissance is the period that began around the 14th century and ended at the late 16th century, traditionally associated primarily with the Italian region. The ideas and images of the Renaissance largely determined the aesthetic ideals of modern man, his sense of harmony, measure and beauty.

The term rinascita (it. revival) was introduced by Giorgio Vasari, who contrasted the new art that revived the ancient culture, and the "dark Middle Ages". By the way, Renaissance figures also called the Middle Ages "dark", thus have they permanently eternized their negative attitude to the Middle Ages. If they only knew that today the search query "the art of the Middle Ages" in search engines returns Renaissance paintings in about 70% of links, then they would certainly get outraged.

The Renaissance era is historically most often attributed to the late Middle Ages, considering this period a "bridge" to the New Age. Nevertheless, the Renaissance worldview is much closer to the New Age and it is the quattrocento that forms the aesthetic canons of modern man, which are firmly entrenched in our minds. To be honest, the aesthetic revolutions of the 20th century never overshadowed or supplanted the Renaissance revolution.

The Renaissance era is historically most often attributed to the late Middle Ages, considering this period a "bridge" to the New Age. Nevertheless, the Renaissance worldview is much closer to the New Age and it is the quattrocento that forms the aesthetic canons of modern man, which are firmly entrenched in our minds. To be honest, the aesthetic revolutions of the 20th century never overshadowed or supplanted the Renaissance revolution.

The head of the angel

1501, 31×27 cm

Renaissance Chronology:

the Proto-Renaissance (2nd half of the 13th — 14th century)

the Early Renaissance (early 14th — 1st of the 15th century)

the High Renaissance (15th — the first third of the 16th century)

the Late Renaissance (mid-16th century — the 1590s)

The main features of the era:

— addressing to the ancient heritage: the art and philosophy of ancient Greece and Rome. In the Middle Ages, the scholasticism addressed to the works of Aristotle, whereas the Renaissance praises Plato and Neoplatonism;

— the Renaissance is the time of transition from an artist-craftsman to an artist-creator, from an unnamed artist to an author. Man becomes like a god, he is the creator on earth, he is the highest being created by the Almighty. The uniqueness of the human person is appreciated. This feature is called anthropocentrism (gr. ἄνθρωπος "man");

— the Renaissance focuses not on theology, but on art and philosophy. The predominance of secular over religious. The Renaissance man is a universally educated person, hence the Renaissance humanism. It’s not your origin that is important now, but how talented you are. Therefore, many Renaissance figures were far from noble families.

the Proto-Renaissance (2nd half of the 13th — 14th century)

the Early Renaissance (early 14th — 1st of the 15th century)

the High Renaissance (15th — the first third of the 16th century)

the Late Renaissance (mid-16th century — the 1590s)

The main features of the era:

— addressing to the ancient heritage: the art and philosophy of ancient Greece and Rome. In the Middle Ages, the scholasticism addressed to the works of Aristotle, whereas the Renaissance praises Plato and Neoplatonism;

— the Renaissance is the time of transition from an artist-craftsman to an artist-creator, from an unnamed artist to an author. Man becomes like a god, he is the creator on earth, he is the highest being created by the Almighty. The uniqueness of the human person is appreciated. This feature is called anthropocentrism (gr. ἄνθρωπος "man");

— the Renaissance focuses not on theology, but on art and philosophy. The predominance of secular over religious. The Renaissance man is a universally educated person, hence the Renaissance humanism. It’s not your origin that is important now, but how talented you are. Therefore, many Renaissance figures were far from noble families.

Portrait of Cosimo Medici

1537, 100.9×77 cm

Italy and the Renaissance

Italy is considered to be the birthplace of the Renaissance, because in the West Europe, Italy is the direct successor of ancient culture. It is noteworthy that Rome, the eternal city that has been under the oppression of barbarians for a millennium, never forgot its former glory, although the primacy in the revival of ancient thought did not belong to Rome, but to Florence. Renaissance titans created their masterpieces in Florence: Brunelleschi, Alberti, Donatello, Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo, Raphael. In Florence, Plato and other Greek philosophers were first translated into Latin. Thanks to the main Renaissance philanthropist Lorenzo Medici, Lorenzo the Magnificent, the Byzantine philosopher Gemistus Pletho, Florentines Marsilio Ficino, Pico della Mirandolla found the so-called Platonic Academy, where they shared their innovative humanistic ideas. Actually, the Renaissance thinkers are called not so much philosophers as humanists, since many of them did not have a complete philosophical system.

Italy is considered to be the birthplace of the Renaissance, because in the West Europe, Italy is the direct successor of ancient culture. It is noteworthy that Rome, the eternal city that has been under the oppression of barbarians for a millennium, never forgot its former glory, although the primacy in the revival of ancient thought did not belong to Rome, but to Florence. Renaissance titans created their masterpieces in Florence: Brunelleschi, Alberti, Donatello, Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo, Raphael. In Florence, Plato and other Greek philosophers were first translated into Latin. Thanks to the main Renaissance philanthropist Lorenzo Medici, Lorenzo the Magnificent, the Byzantine philosopher Gemistus Pletho, Florentines Marsilio Ficino, Pico della Mirandolla found the so-called Platonic Academy, where they shared their innovative humanistic ideas. Actually, the Renaissance thinkers are called not so much philosophers as humanists, since many of them did not have a complete philosophical system.

Portrait of Pico della Mirandola from the Giovio series

The humanism of the Renaissance had a special meaning and a special interpretation.

— Actively referring to all times, developing a "surplus of vision" in the symbolic sphere, the Renaissance develops a special kind of penetrating diplomatic courtesy in itself. This courtesy is one of the main features of "humanism". Renaissance humanism is not a glorification of the human, the humanocentrism that crushes the dark ages, but is just the trends of the Enlightenment brought into this concept. Antique humanitas, the closest analogue is the Greek word for education, implies, first of all, dignity, kindness, education, courtesy, affability.

— Actively referring to all times, developing a "surplus of vision" in the symbolic sphere, the Renaissance develops a special kind of penetrating diplomatic courtesy in itself. This courtesy is one of the main features of "humanism". Renaissance humanism is not a glorification of the human, the humanocentrism that crushes the dark ages, but is just the trends of the Enlightenment brought into this concept. Antique humanitas, the closest analogue is the Greek word for education, implies, first of all, dignity, kindness, education, courtesy, affability.

A. F. Losev "Aesthetics of the Renaissance"

The turning point

The Proto-Renaissance (13th—14th centuries) not only laid the foundations for a future coup, it is the birth time of radically new ideas. The approval of the scholasticism with its motto by Thomas Aquinas "Philosophy is the servant of theology" on the one hand, and its denial on the other hand. Philosophers such as Scot Duns Scotus, the German mystic Meister Eckhart, Nicholas of Cusa form a completely new idea of man and his place in the universe. Man becomes not just God’s creation (creature), man is a person through whom God knows himself, through which God manifests himself in His entirety. The philosophy of Nicholas of Cusa had a huge impact on the art of the Northern Renaissance, filled with pantheism and divine principles.

The Proto-Renaissance (13th—14th centuries) not only laid the foundations for a future coup, it is the birth time of radically new ideas. The approval of the scholasticism with its motto by Thomas Aquinas "Philosophy is the servant of theology" on the one hand, and its denial on the other hand. Philosophers such as Scot Duns Scotus, the German mystic Meister Eckhart, Nicholas of Cusa form a completely new idea of man and his place in the universe. Man becomes not just God’s creation (creature), man is a person through whom God knows himself, through which God manifests himself in His entirety. The philosophy of Nicholas of Cusa had a huge impact on the art of the Northern Renaissance, filled with pantheism and divine principles.

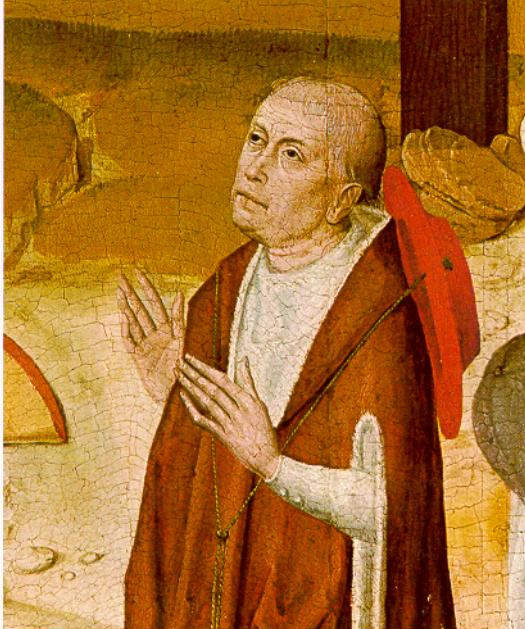

Nicholas of Cusa (c. 1480. Detail of the work by an artist, known as the Master of the Life of the Virgin)

The works by Robert Kampen and Rogier van der Weyden, the founders of the Northern Renaissance, clearly show how the idea of pantheism was embodied in painting.

Another excellent example is the work by an unknown Dutch master of the 15th century, Madonna of Humility. This is no longer a schematic-sacred image of Byzantine icons. Madonna looks at the little Christ with motherly gentleness, He holds an apple in His hands, the symbol of salvation. However, He does not demonstrate it to the viewer deliberately, but, like a child, plays with it. The objects seem to live their quiet lives, unobtrusively revealing the image. Such an image of the Madonna in a closed garden hints at the Mary’s Immaculate Conception, and white lilies represent her innocence. Small red flowers are the symbol of the sacrificial blood of Jesus.

In a broad manner, to understand the Renaissance painting, you need to peer into it. Aby Warburg’s famous phrase "God is in the details" is directly related to Renaissance art.

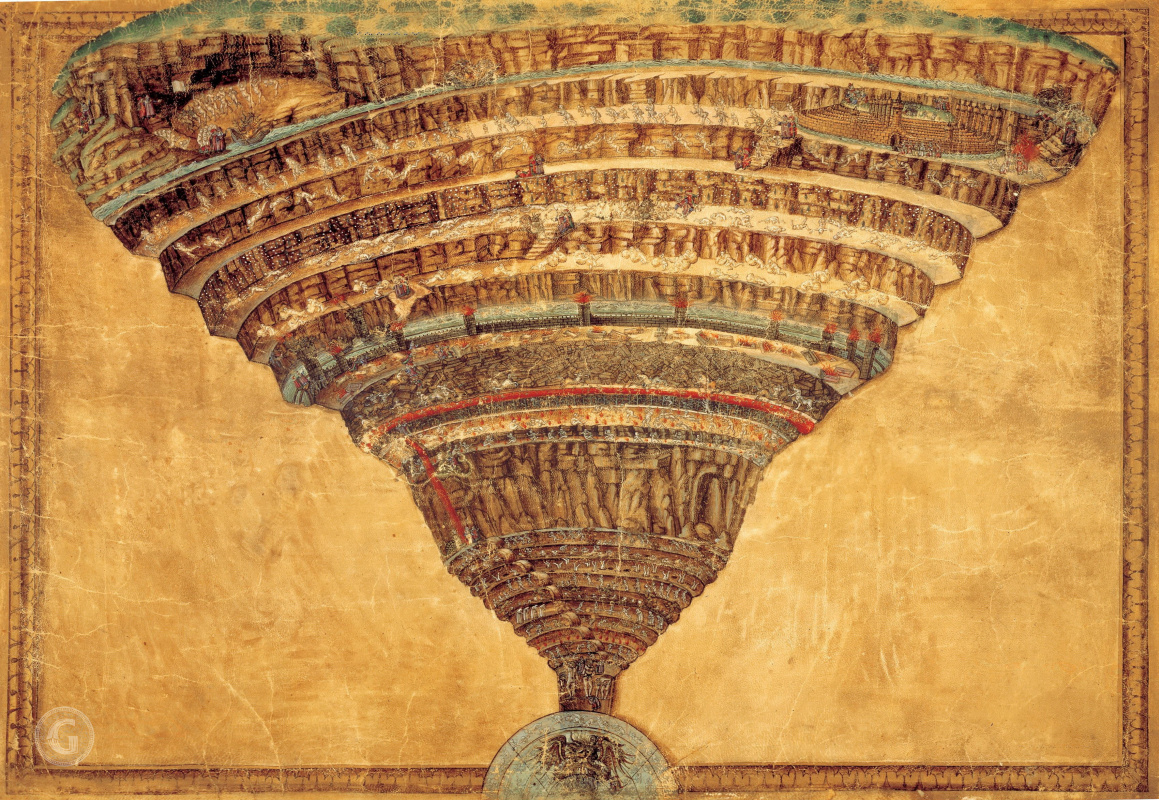

Dante and Giotto

Dante Alighieri is considered the forerunner of the Renaissance in literature, while in painting it was Giotto di Bondone. As friends, Dante and Giotto managed to create a new language and new imagery. The Divine Comedy, that Dante wrote in exile, is not a traditional medieval clerical genre of vision, where a saint or an angel descends into hellish depths. This is a journey through the hell of the author himself, who is accompanied by none other than the pagan — the Roman poet Virgil. The Comedy (this was the original name of the work, the epithet "divine" appeared a bit later), is filled with allegories and anachronism . Dante placed into hell the departed sinners, as well as his still living contemporaries, who were the poet’s political enemies. At the same time, going down deeper, Dante cannot hide his sympathy for many sufferers, and this is an important moment of the personal compassion and individual experience. Dante described the circles of Hell in such detail, as if he had actually been there.

Dante Alighieri is considered the forerunner of the Renaissance in literature, while in painting it was Giotto di Bondone. As friends, Dante and Giotto managed to create a new language and new imagery. The Divine Comedy, that Dante wrote in exile, is not a traditional medieval clerical genre of vision, where a saint or an angel descends into hellish depths. This is a journey through the hell of the author himself, who is accompanied by none other than the pagan — the Roman poet Virgil. The Comedy (this was the original name of the work, the epithet "divine" appeared a bit later), is filled with allegories and anachronism . Dante placed into hell the departed sinners, as well as his still living contemporaries, who were the poet’s political enemies. At the same time, going down deeper, Dante cannot hide his sympathy for many sufferers, and this is an important moment of the personal compassion and individual experience. Dante described the circles of Hell in such detail, as if he had actually been there.

A similar materiality and realism

appear in the Giotto’s frescoes. One of the most expressive works by Giotto is The Lamentation of Christ, which demonstrates the emotional nuances of the inner turmoil of saints and suffering angels. On this fresco, the trecento master created a wide range of feelings, diversifying his grieving heroes.

As for the innovation of the visual language, Giotto was the first artist to abandon the golden background in favour of the blue sky, landscapes and a hint of perspective and volume appear in his painting. And in his Padua frescoes The Last Judgment, Giotto made his self-portrait (at least, it is commonly believed in art history) and put himself among the righteous. Following him, quattrocento would actively use this method, shortening the distance between the sacred and the profane more and more.

Feeling the finiteness of human being

Exalting the human person, creating the image of a god-like creator, the Renaissance also keenly felt the finiteness of human life. This tragedy is sharply expressed in the poetry of Francesco Petrarca, the creator of the new European lyrics. In a number of his sonnets, he wants to get rid of the torment of love by finding death, but also he makes it clear that there is an unknown world on the other side of life. His sonnets are spiritualized and at the same time very understandable to the modern reader, because he describes the feelings of a living person.

His younger contemporary Giovanni Boccaccio, the founder of the modern short story, wrote the ironic and philosophical collection Decameron, in which psychologism appears, albeit schematically. The most important thing here is the lack of didactics traditional for the Italian short story. Ten heroes of the Decameron leave the city during the plague (punishment of the Lord) and within ten days tell each other heart-warming stories full of romance and eroticism. This collection of stories clearly demonstrates the opinion of the author himself. Boccaccio expatiates upon how God created man as a man and woman as a woman, and that both the righteous and sinners ultimately die from the plague. So why not fight the scourge and enjoy the life that would pass so far?

Exalting the human person, creating the image of a god-like creator, the Renaissance also keenly felt the finiteness of human life. This tragedy is sharply expressed in the poetry of Francesco Petrarca, the creator of the new European lyrics. In a number of his sonnets, he wants to get rid of the torment of love by finding death, but also he makes it clear that there is an unknown world on the other side of life. His sonnets are spiritualized and at the same time very understandable to the modern reader, because he describes the feelings of a living person.

His younger contemporary Giovanni Boccaccio, the founder of the modern short story, wrote the ironic and philosophical collection Decameron, in which psychologism appears, albeit schematically. The most important thing here is the lack of didactics traditional for the Italian short story. Ten heroes of the Decameron leave the city during the plague (punishment of the Lord) and within ten days tell each other heart-warming stories full of romance and eroticism. This collection of stories clearly demonstrates the opinion of the author himself. Boccaccio expatiates upon how God created man as a man and woman as a woman, and that both the righteous and sinners ultimately die from the plague. So why not fight the scourge and enjoy the life that would pass so far?

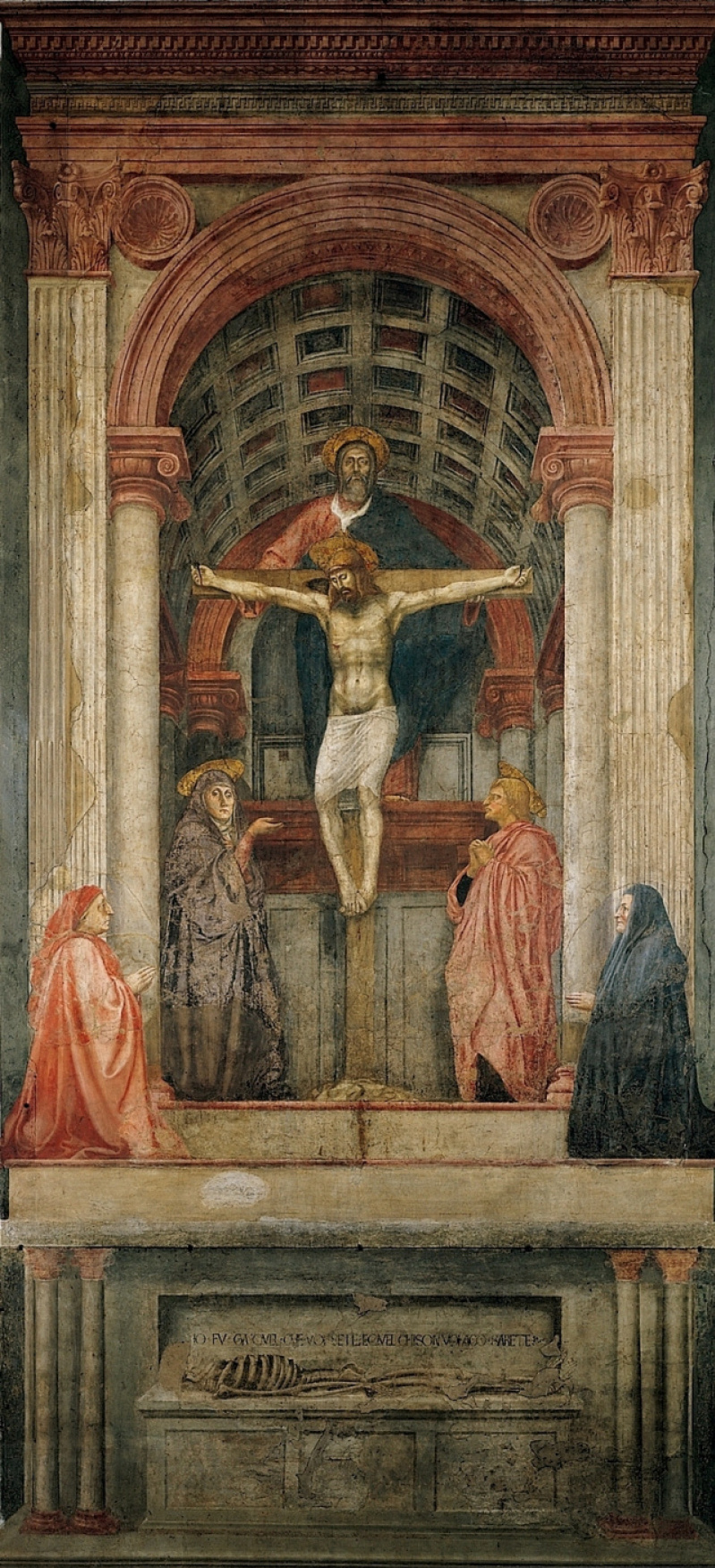

The Holy Trinity

1428, 667×317 cm

We see similar attitudes in the painting by Masaccio in the Trinity fresco. An innovative transfer of perspective and harmonious integration of people’s figures into it already appear here: instead of artificial emphasizing the "ranked" significance of figures by distorting their sizes, God the Father, God the Son, Virgin Mary, the Apostle John and the donors are painted in the same size. Masaccio only places them at different heights. At the very bottom is the coffin with Adam, the first person with the inscription: "I was like you, you will be like me". As you can see, the memento mori motive, which became so popular later in the 17th century, began to manifest itself already in the early Renaissance. And the ode to human death is The Dead Christ by Andrea Mantegna. An unusual perspective makes it possible to see Jesus not as a schematic detached profile image, but as a body lying in front of us. The pacified, calm expression of Christ’s face contrasts sharply with the suffering Mary and John. You can see right away that death rules in this room.

Dead Christ (Mourning the Dead Christ)

1483, 81×66 cm

The perspective

The direct and linear perspective is the find and cult of the Renaissance. Quattrocento artists demonstrate their mastery of perspective knowledge. For a medieval man, the sky had a special attraction; for a Renaissance man, such an attraction has the horizon and landscape . With the help of scientific knowledge, geometry and mathematics, artists create an ideal world, not just imitating nature, but transforming it.

The first perspective statement belongs to the Florentine architect Filippo Brunelleschi. However, Brunelleschi did not explain the laws of perspective. This was done in the "On Painting" treatise by the architect and writer Leon Battista Alberti. Alberti called perspective "a window" through which we look into space. This definition has not only descriptive, but also philosophical meaning. Using the inverted perspective, the icon placed a person in its heavenly world, creating the effect of "here-being". Quattrocento pictures alienate the space of painting from the space of the viewer, demonstrating the world in the picture, going into another dimension — the artistic one. Great attention was paid to the perspective by Paolo Uccello, artist of the early Renaissance. According to Vasari, known was known to draw all day long, he connected straight lines, contoured architectural elements. In his painting, there is not yet that ideal perspective of the high Renaissance, but certain developments are already visible: figures located closer to the viewer are larger, those that are further appear smaller depending on their place on the canvas, but not status.

The direct and linear perspective is the find and cult of the Renaissance. Quattrocento artists demonstrate their mastery of perspective knowledge. For a medieval man, the sky had a special attraction; for a Renaissance man, such an attraction has the horizon and landscape . With the help of scientific knowledge, geometry and mathematics, artists create an ideal world, not just imitating nature, but transforming it.

The first perspective statement belongs to the Florentine architect Filippo Brunelleschi. However, Brunelleschi did not explain the laws of perspective. This was done in the "On Painting" treatise by the architect and writer Leon Battista Alberti. Alberti called perspective "a window" through which we look into space. This definition has not only descriptive, but also philosophical meaning. Using the inverted perspective, the icon placed a person in its heavenly world, creating the effect of "here-being". Quattrocento pictures alienate the space of painting from the space of the viewer, demonstrating the world in the picture, going into another dimension — the artistic one. Great attention was paid to the perspective by Paolo Uccello, artist of the early Renaissance. According to Vasari, known was known to draw all day long, he connected straight lines, contoured architectural elements. In his painting, there is not yet that ideal perspective of the high Renaissance, but certain developments are already visible: figures located closer to the viewer are larger, those that are further appear smaller depending on their place on the canvas, but not status.

Scenes from the life of hermits

109×80 cm

Piero della Francesca is another artist who is rightly called the father of linear perspective. He wrote a treatise "On Perspective in Painting", where he brought the perspective doctrine to the theoretical and practical level. In the Northern Renaissance, the problem of perspective was dealt with in detail by Albrecht Dürer. And, of course, one of the most famous figures of the Renaissance, Leonardo da Vinci didn’t ignore this issue and wrote a work "On Painting and Perspective", in which he polemicized with his predecessors, identifying three types of perspective: linear, aerial and picturesque.

Also read

Northern Renaissance

Portrait in the Renaissance era

The long period of the Middle Ages did not know the portrait genre. Only the characters from the Bible were worthy of being portrayed, and since they are representatives of the divine world, their images were conditional, canonical and symbolic. The first sculptural portraits began to appear in the Gothic cathedrals. The medieval portrait is very versatile and associated with the class hierarchy, most often it depicted representatives of authority and chivalry. Realism in portraits is a feature of the Renaissance. The first portrait images are profile, but in them, it is already possible to see the individualization of the portrayed person. The Portrait of Sigismundo Malatesta by Piero della Francesca is a perfect example of such a portrait where we have a very contradictory personality. Malatesta was a humanist and one of the Renaissance patrons, he was also a condottiere and a cruel killer, so his inner harshness did not escape della Francesca’s gaze.

The long period of the Middle Ages did not know the portrait genre. Only the characters from the Bible were worthy of being portrayed, and since they are representatives of the divine world, their images were conditional, canonical and symbolic. The first sculptural portraits began to appear in the Gothic cathedrals. The medieval portrait is very versatile and associated with the class hierarchy, most often it depicted representatives of authority and chivalry. Realism in portraits is a feature of the Renaissance. The first portrait images are profile, but in them, it is already possible to see the individualization of the portrayed person. The Portrait of Sigismundo Malatesta by Piero della Francesca is a perfect example of such a portrait where we have a very contradictory personality. Malatesta was a humanist and one of the Renaissance patrons, he was also a condottiere and a cruel killer, so his inner harshness did not escape della Francesca’s gaze.

Portrait Direction Of Sigismondo Malatesta

1451, 44×34 cm

Along with the characteristic nuances of appearance, symbolism

also plays an important role. Jacopo Patorno’s Portrait of Cosimo de' Medici, painted more than half a century after Cosimo’s death, shows a slightly withered figure of an elderly man looking at a laurel tree — the emblem of the Medici genus, an ancient symbol of glory, and during the Renaissance, poets were crowned with laurels. There are lines from "Aeneid" by Virgil woven in the tree, reminding once again of the love of Cosimo and the whole era to Antiquity.

Jacopo Patorno. Portrait of Cosimo de' Medici

Gradually, the portrayed person turned to the viewer and, of course, this is due to a worldview change. Andrea Solario’s Man with a Pink Carnation is the embodiment of the Renaissance attitude to the man in a portrait where the typical and characteristic, human, is combined with haughty nobility and detachment.

The quattrocento’s apex of portrait art is Mona Lisa, which attracts the viewer with its mysteriousness.

Mona Lisa (La Gioconda)

1500-th

, 77×53 cm

The traits of real people were seen not only in portraits but also in religious images. The modest role of the donor is being replaced by the victory of the worldly over the supernal, and more and more real people can be recognized in the images of the Virgin and the saints. For example, Botticelli’s work The Adoration of the Magi depicts a whole family portrait of the Medici dynasty and a self-portrait of the artist himself. In the right corner of the Roman ruins, we see a peacock — the symbol of immortality, not only that of the Christian faith, but also of the Florentine dynasty.

The adoration of the Magi

1475, 111×134 cm

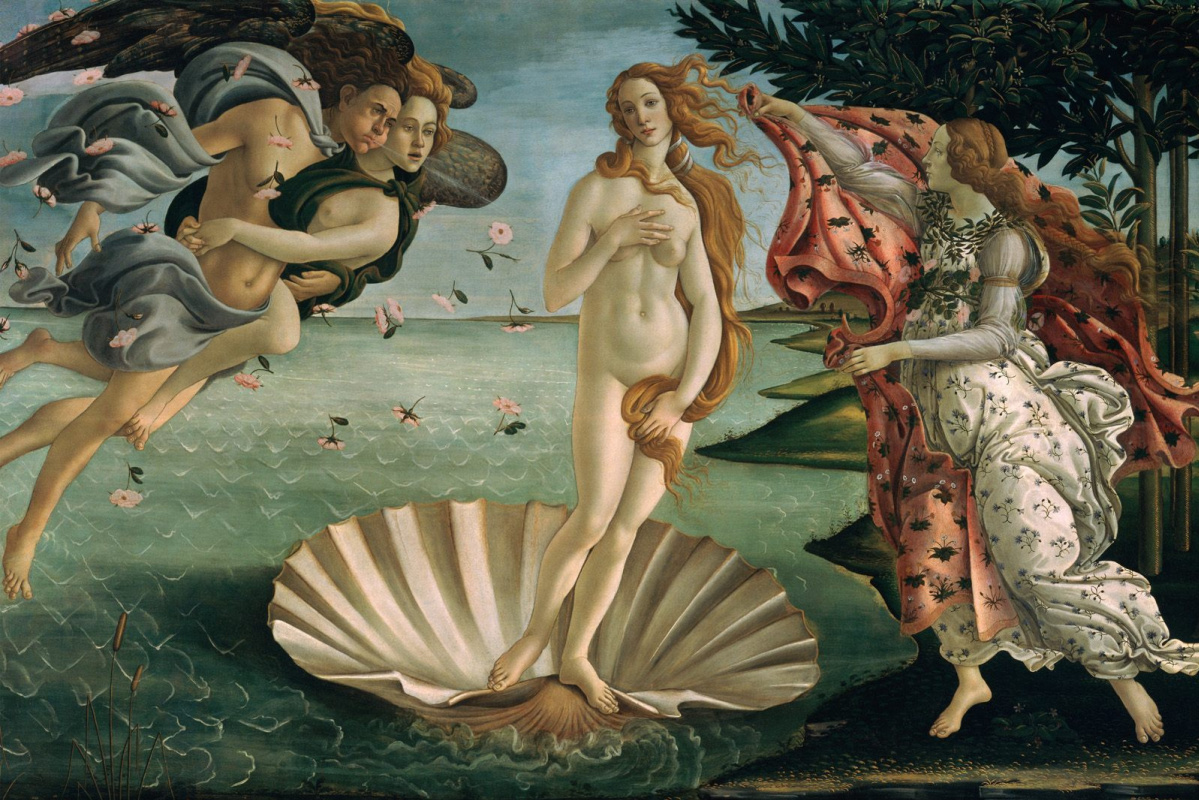

Botticelli’s Primavera and Venus

In the Renaissance, ancient mythology is intertwined with Christianity, interpretations of images become ambiguous and an important role in the Renaissance iconography is occupied by the goddess of love associated with Nature. The medieval understanding of Venus considered her symbol of carnal delights, whereas the quattrocento makes the goddess an ideal of spirituality, and Sandro Botticelli played the major role in the formation of such an ideal. It is believed that The Birth of Venus and Primavera are painted for the Medici family; the works themselves are intertwined. Botticelli’s favorite model was Simonetta Vispucci, the beauty of the Florence court, beloved of Giuliano Medici. The face of this lady adorns many paintings of the artist, she appears both as a goddess of love, and the Virgin. The Venus combines two principles: the Christian and pagan, but paganism is rather refined, Christianized. However, we find here some points of pagan understanding of the world. The appearance of the Venus is close to the sublime appearance of the Virgin Mary — this is primarily seen in the tilt of her head. The shy pose is in harmony with the Capitoline Venus, an ancient sculpture. A foam-born goddess, driven by Zephyrus and his wife, Flora , who strews her with roses. Rose is a symbolic flower, it is depicted both with Venus and with Madonna. The nymph takes the goddess of love ashore and throws a veil on her. According to Ernst Gombrich, newborns and dead were wrapped in such covers in ancient Greece, and he draws a parallel between the Venus and the Baptism, where the iconographic similarity is obvious. In this case, birth and baptism are both the transition from one state to another.

In the Renaissance, ancient mythology is intertwined with Christianity, interpretations of images become ambiguous and an important role in the Renaissance iconography is occupied by the goddess of love associated with Nature. The medieval understanding of Venus considered her symbol of carnal delights, whereas the quattrocento makes the goddess an ideal of spirituality, and Sandro Botticelli played the major role in the formation of such an ideal. It is believed that The Birth of Venus and Primavera are painted for the Medici family; the works themselves are intertwined. Botticelli’s favorite model was Simonetta Vispucci, the beauty of the Florence court, beloved of Giuliano Medici. The face of this lady adorns many paintings of the artist, she appears both as a goddess of love, and the Virgin. The Venus combines two principles: the Christian and pagan, but paganism is rather refined, Christianized. However, we find here some points of pagan understanding of the world. The appearance of the Venus is close to the sublime appearance of the Virgin Mary — this is primarily seen in the tilt of her head. The shy pose is in harmony with the Capitoline Venus, an ancient sculpture. A foam-born goddess, driven by Zephyrus and his wife, Flora , who strews her with roses. Rose is a symbolic flower, it is depicted both with Venus and with Madonna. The nymph takes the goddess of love ashore and throws a veil on her. According to Ernst Gombrich, newborns and dead were wrapped in such covers in ancient Greece, and he draws a parallel between the Venus and the Baptism, where the iconographic similarity is obvious. In this case, birth and baptism are both the transition from one state to another.

Birth Of Venus

1486, 172.5×278.5 cm

The Primavera deepens the transition theme. At the centre, we see Venus with a Christian gesture of blessing. She is obviously Venus, because there is Cupid, the satellite of the goddess, aiming at one of their Graces. The three graces are often associated with different forms of love. Behind Venus, there is an orange tree: the symbol of the Virgin and the Medici; the trees are reminiscent of the image of Mary in a closed garden, symbolizing her innocence. To the right, there are Zephyrus and Chloris the nymph during her turning into Flora

, meaning the transition from worldly to heavenly. In antiquity, Mercury was considered a mediator between heaven, earth and the underworld. The closed image is reminiscent of cyclicality and eternal rebirth. In this case Botticelli painted not the Eden garden with the paradise place inherent in the Christian worldview, but the birth and death of nature inherent in pagan understanding.

Spring

1485, 314×203 cm

Artchive’s Crib. Important discoveries of the Renaissance

— In the Renaissance era, there occurred a transition from the geocentric model of the world to the heliocentric one. Executed by the Inquisition for holding opinions contrary to the Catholic faith about Trinity, Christ, the Virgin, Giordano Bruno argued the existence of new potential worlds; the Earth is not considered the only planet created by God anymore.

— Columbus discovers the New World in 1492, and some historians have been counting the New Age since the discovery of America.

— Archeology, book printing and national languages are developing a totally new status.

— The authority centre shifts from church to secular.

— Art, science, philosophy move away from theology and become the dominant of social life.

You are a layman if:

— You believe that the Renaissance is a purely Italian phenomenon;

— You think that the Inquisition is a part of the Middle Ages.

You are an expert if:

— You know that the Renaissance is the first epoch to give itself a name;

— You know that oil paint was first used in the Renaissance;

— You like to look into the details of Renaissance paintings and know about the hidden symbolic motives of many of them.

— In the Renaissance era, there occurred a transition from the geocentric model of the world to the heliocentric one. Executed by the Inquisition for holding opinions contrary to the Catholic faith about Trinity, Christ, the Virgin, Giordano Bruno argued the existence of new potential worlds; the Earth is not considered the only planet created by God anymore.

— Columbus discovers the New World in 1492, and some historians have been counting the New Age since the discovery of America.

— Archeology, book printing and national languages are developing a totally new status.

— The authority centre shifts from church to secular.

— Art, science, philosophy move away from theology and become the dominant of social life.

You are a layman if:

— You believe that the Renaissance is a purely Italian phenomenon;

— You think that the Inquisition is a part of the Middle Ages.

You are an expert if:

— You know that the Renaissance is the first epoch to give itself a name;

— You know that oil paint was first used in the Renaissance;

— You like to look into the details of Renaissance paintings and know about the hidden symbolic motives of many of them.