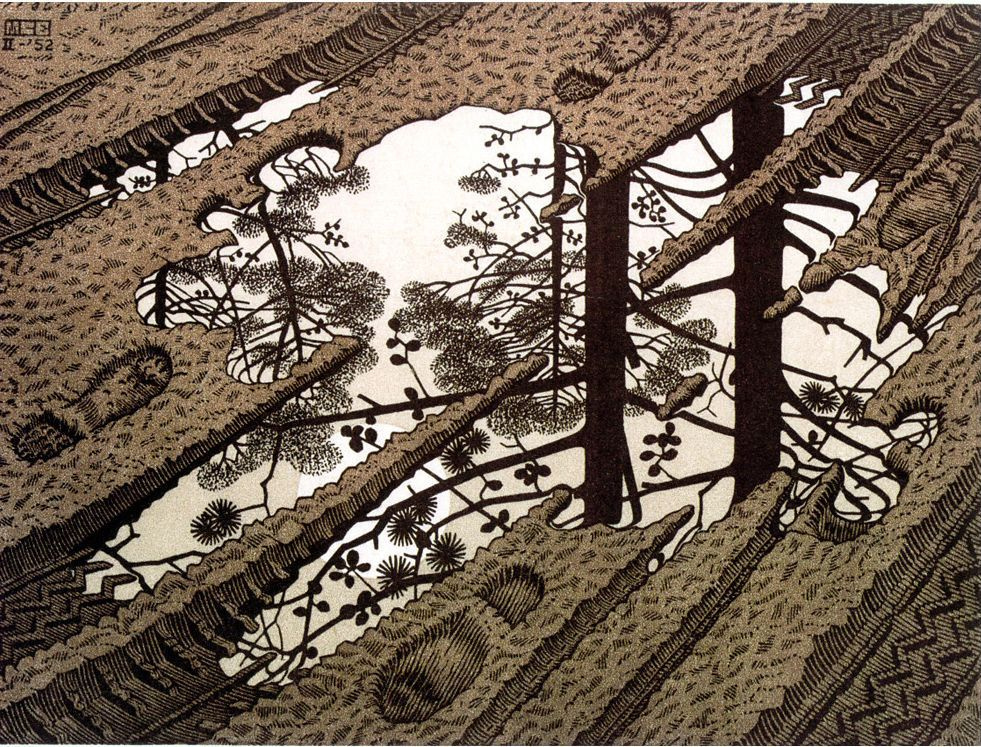

Puddle

Description of the artwork «Puddle»

“The cloudless evening sky is reflected in a puddle, which appeared on a forest path after a recent rainstorm. The traces of two car tires, two bicycle wheels and the shoes of two pedestrians were imprinted on the clay soil”, the Dutch artist Maurits Cornelis Escher (1898—1972) described this work almost mathematically.

Well, the subject is really devoid of spectacular pretentiousness and seems rather simple. The master invented and embodied it in 1952 — his mature years, the peak of his artistic skills. Moreover, this Puddle also absorbed his early graphic experience: during the 11 years that the artist lived with his wife Jetta in Italy, he captured a lot of traditional landscapes: he later transformed drawings from nature into graphics. There are also Japanese larch trees in his “Italian” portfolio — ordinary trees on the shore, opposite a hill with many houses on it. Afterwards, the artist began to rethink and transform reality in his works, building a kind of parallel world.

Maurits Escher became famous for his graphic works just in the 1950s (recall, Puddle appeared in 1952), but the so-called paradoxical artworks brought him wide recognition: ornaments with objects gradually transitioning into each other, as well as compositions with impossible geometry. Why is this discreet work considered one of the most famous ones? It is unlikely that the reason is only in the artist’s choice for the album of his best works, which contained 72 engravings out of almost five hundred Escher’s works. Escher wanted to present a selection of the subjects that revealed the main ideas of his work and showed his skill. Well, the work called Puddle belongs to one of his typical themes, it presents an interpretation of Escher’s constant leitmotif, the meeting of the elements.

Earth, water, and air in its unusual form, the reflection of space in the surface of the water. A true explorer, with a keen sense of the nature of things, Escher also highlighted an active human presence, perhaps also his own presence, depicted the prints of bicycle tires, car wheels and, finally, clearly and deeply imprinted shoe footprints. And where did everyone go? However, it did not matter. The artist showed things, which are not there: airspace, gone machines, and some passers-by, whose universes do not intersect — traces diverge in opposite directions... The viewer seems to find oneself in the soundless world of Stephen King’s Langoliers, which is different for a second and fading in time, or in one of the similar worlds different from ours, which were described in the Ring Around the Sun by Clifford D. Simak. This is where we recall the opening words of the film adaptation of the Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings: “The world has changed...”

“The Wrong Side of Reality,” is how Mickey Piller, the curator at the Escher Museum in The Hague, called this work; in her essay she also draws attention to the unusual colour scheme of the engraving. Instead of the black-and-white distribution usual for Escher’s works, here we see brown clay and a greenish moon — the shade that seems light grey and gives an extraordinary expressiveness to the round luminary (to see and appreciate this, you should see the original engraving by the artist).

Escher made his Puddle in his favourite technique, the so-called longitudinal woodcut (according to the artist’s description, “three boards”). Longitudinal (and not transverse, which is more common) cuts of wood, pear tree, were also preferred by the artist’s favourite teacher Samuel de Mesquita. A small divagation to continue the theme of footprints: de Mesquita died in Auschwitz. Escher helped send the teacher’s work to the Stedelik Museum in Amsterdam, and left only one drawing — a sketch with a footstep of a German boot. It would be wrong to lose this fact when talking about the famous engraving with the objects so iconic for the artist.

He also used his typical techniques to visually emphasize the idea of the overlapping worlds. This is a juxtaposition of lines and planes: sharp contours of “torn” edges of the puddle, longitudinal tire tracks, and interweaving of tree branches that are clearly “inscribed” into the plane of water (and the graphic sheet), but the true angle, position and scale of things are still guessed. When Escher created the work, the trees were large.

The Puddle, an unpretentious work at first glance, gets firmly imprinted in the mind of the viewer, and finally turns out to be a deep investigation, a mystery, the artist’s thought of the nodal points and space junctions, on the passing, fleeting and unchanging. As well as his another famous engraving Three Worlds (1955), which was created afterwards. There we see the fallen leaves on the surface of the reservoir, reflection of trees, fish. Here we see the moon, Japanese larches, footprints in clay and sand. Material and invisible, yet seen and shown to us by Escher. Moreover, the artist did not really anticipate understanding: “No matter how objective or impartial my themes seem to me, as far as I know, only a few (if they exist at all) treat the world around us the same way as I do.”

Author: Olha Potekhina