log in

Enter site

Login to use Arthive functionality to the maximum

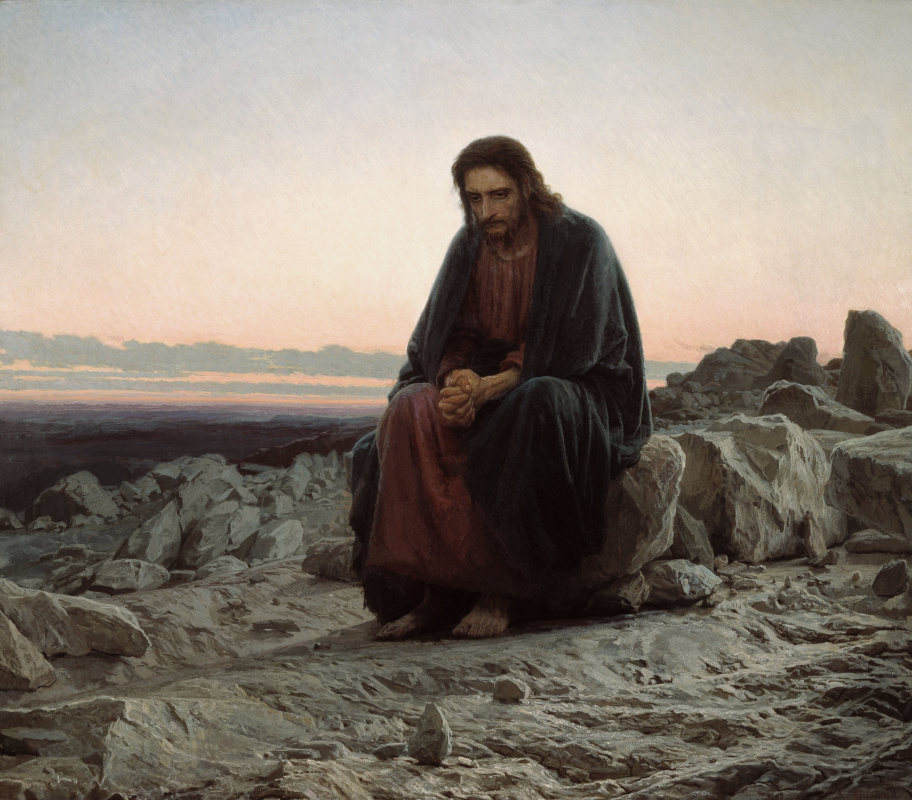

Christ in the wilderness

Ivan Nikolayevich Kramskoy • Painting, 1872, 180×210 cm

Description of the artwork «Christ in the wilderness»

Kramskoy confessed that he painted his Christ in the Wilderness with tears and blood. He worked on it for a long time, created sketches, discarded them, looking for the necessary vein. The theme of the temptation of Christ occupied him even during his studies at the Academy. The first impetus was Alexandr Ivanov’s painting, The appearance of Christ to the People. Kramskoy was deeply moved by this work. For himself, he formulated the task as follows: to put a mirror in front of people, which would make their hearts sound the alarm. For 10 years, he constantly returned to the picture, painted sketches. The version of 1867 is known, but the artist considered it unsuccessful. Indeed, the vertical format lacked width, boundlessness, and the “context” in which the Saviour, immersed in thought, was enclosed. Two years later, Kramskoy went to Europe. Examining the works by recognized masters, he kept his image in mind all the time, compared it with other interpretations, grope for the right solution. He finished painting in Crimea, he woke up early and could spend the whole day at the canvas — he already knew what it should be like.

The subject of the picture is taken from the New Testament, the temptation of Christ in the desert, where He retired for 40 days after His baptism. Christ by Kramskoy, like the Christ in the Garden of Gethsemane by Ge, does not look like a King, but a suffering, restless, and doubting person.

Kramskoy wanted to show the moment of moral choice. There is no external action in the picture; it was replaced by the inner experience of the subject. In fact, the subject matter of the picture is the very life of the spirit. In a well-known letter to Vsevolod Garshin, the artist gave explanations to the picture: “I see clearly that there is one moment in the life of every person created in the image and likeness of God to some extent, when he thinks about whether to go to the right or to the left, whether to sell Lord God for a rouble or not to yield a step to the evil?” It was at the moment of such thoughts that the Son of God was captured on the picture.

The composition of the painting is flawless. The face and hands of Christ are two centres that attract the eye, everything else seems to be painted around them. On His face, there are traces of painful thoughts. He could say:

If only it is possible,

Abba, Father,

May this cup be carried past me.

(B. Pasternak, translated by Eleanor Rowe)

However, there is already in His face both humility and acceptance of His fate. The cup will not be carried past Him, He will drink it to the bottom. The horizon line divides the picture into two worlds: a cold, lifeless desert and a rising dawn. This glow of a new day seems to proclaim the victory of light. The tightly clenched hands of Christ are located exactly at the junction of the worlds — with these hands the new life will be created. Christ’s feet are wounded on stones, they make you feel as if you are touching something that hurts. Bloody feet bring their element to the subject; looking at them, we understand that the morning reflections were preceded by a sleepless night, a long restless way through the darkness. Dawn is coming — and this path is coming to its end.

Critics reproached Kramskoy for the fact that there was not enough holiness in the appearance of his Christ, He is too alive and feeling, they said. But this is a reproach that is more like praise. Kramskoy exhibited the Christ in the Wilderness painting at the second exhibition of the Itinerants. It made a splash. The artist confessed that there were not three people who would adhere to one view of his Christ.

Kramskoy himself believed that no one was able to really see his picture and hear what he was trying to say with it. However, there were many who wanted to buy the canvas. As a result, it went to Pavel Tretyakov, who gave six thousand roubles requested by the artist. Later, the collector admitted that this was one of his favourite works. And Kramskoy promised: “To be continued...” Unfortunately, it was not continued. There was an attempt, for many years he worked on the Laughter painting (alternative titles: Hail, King of the Jews!, Christ in Pilate’s Court), in which he wanted to depict the ridicule of Christ after the trial of Pontius Pilate. With all his soul, Kramskoy strove to work on this picture. However, the need to constantly paint portraits to provide for his family, the death of his two beloved sons and his ruined health prevented him from completing the Laughter. The unfinished painting is now kept in the St. Petersburg Russian Museum.

Written by Aliona Esaulova

The subject of the picture is taken from the New Testament, the temptation of Christ in the desert, where He retired for 40 days after His baptism. Christ by Kramskoy, like the Christ in the Garden of Gethsemane by Ge, does not look like a King, but a suffering, restless, and doubting person.

Kramskoy wanted to show the moment of moral choice. There is no external action in the picture; it was replaced by the inner experience of the subject. In fact, the subject matter of the picture is the very life of the spirit. In a well-known letter to Vsevolod Garshin, the artist gave explanations to the picture: “I see clearly that there is one moment in the life of every person created in the image and likeness of God to some extent, when he thinks about whether to go to the right or to the left, whether to sell Lord God for a rouble or not to yield a step to the evil?” It was at the moment of such thoughts that the Son of God was captured on the picture.

The composition of the painting is flawless. The face and hands of Christ are two centres that attract the eye, everything else seems to be painted around them. On His face, there are traces of painful thoughts. He could say:

If only it is possible,

Abba, Father,

May this cup be carried past me.

(B. Pasternak, translated by Eleanor Rowe)

However, there is already in His face both humility and acceptance of His fate. The cup will not be carried past Him, He will drink it to the bottom. The horizon line divides the picture into two worlds: a cold, lifeless desert and a rising dawn. This glow of a new day seems to proclaim the victory of light. The tightly clenched hands of Christ are located exactly at the junction of the worlds — with these hands the new life will be created. Christ’s feet are wounded on stones, they make you feel as if you are touching something that hurts. Bloody feet bring their element to the subject; looking at them, we understand that the morning reflections were preceded by a sleepless night, a long restless way through the darkness. Dawn is coming — and this path is coming to its end.

Critics reproached Kramskoy for the fact that there was not enough holiness in the appearance of his Christ, He is too alive and feeling, they said. But this is a reproach that is more like praise. Kramskoy exhibited the Christ in the Wilderness painting at the second exhibition of the Itinerants. It made a splash. The artist confessed that there were not three people who would adhere to one view of his Christ.

Kramskoy himself believed that no one was able to really see his picture and hear what he was trying to say with it. However, there were many who wanted to buy the canvas. As a result, it went to Pavel Tretyakov, who gave six thousand roubles requested by the artist. Later, the collector admitted that this was one of his favourite works. And Kramskoy promised: “To be continued...” Unfortunately, it was not continued. There was an attempt, for many years he worked on the Laughter painting (alternative titles: Hail, King of the Jews!, Christ in Pilate’s Court), in which he wanted to depict the ridicule of Christ after the trial of Pontius Pilate. With all his soul, Kramskoy strove to work on this picture. However, the need to constantly paint portraits to provide for his family, the death of his two beloved sons and his ruined health prevented him from completing the Laughter. The unfinished painting is now kept in the St. Petersburg Russian Museum.

Written by Aliona Esaulova