log in

Enter site

Login to use Arthive functionality to the maximum

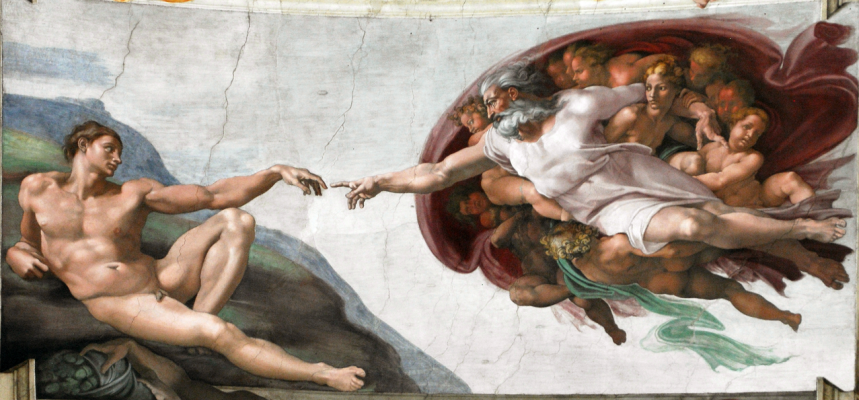

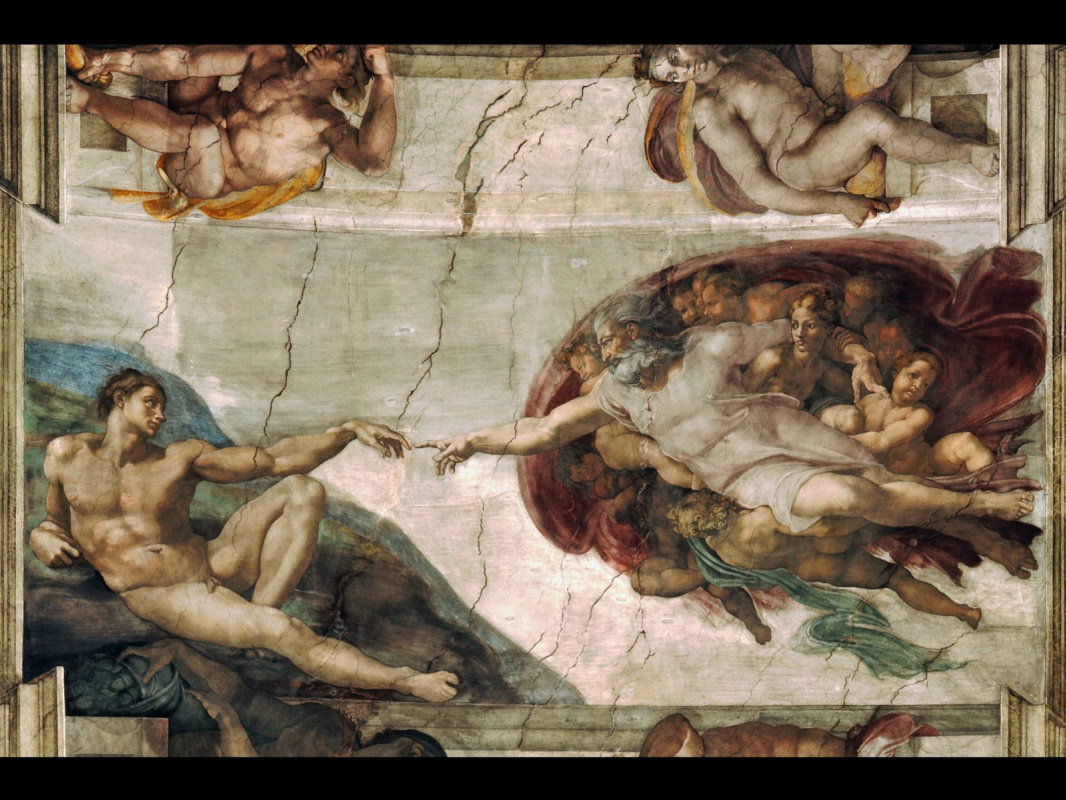

The Creation Of Adam

Michelangelo Buonarroti • Fresco, 1511, 570×280 cm

Description of the artwork «The Creation Of Adam»

Michelangelo di Lodovico Buonarroti Simoni’s Creation of Adam (1508–1512 Museum Sistine Chapel, Vatican City) is, along with Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa, one of the most famous and iconic images in the history of art. As part of the ceiling frescos commissioned by Pope Julius II (1444–1513) for the Sistine Chapel in 1508, it has been celebrated, analyzed, parodied, and debated, and it, more than almost anything else, has shaped the way the public imagined God, Adam, angels, and the Biblical creation of mankind. Esthetically, it is balanced and dynamic, and Adam’s muscular, youthful body draws on earlier Greek and Roman classical art as well as Michelangelo’s extensive knowledge of proportion and anatomy. Though at first glance it seems like a straightforward depiction of God granting Adam the spark of life as described in the Book of Genesis, like much Renaissance art it holds secret messages that art historians and the general public are still trying to decipher centuries later.

The focal point of the Creation of Adam is the almost touching fingers of the first human and his creator. Michelangelo masterfully painted them as close to making contact as possible, leaving us to wonder whether this the moment just before God touches Adam, giving him life and representing the union of the earthly and the divine, or just after it, representing their separation. Adam is shown in a relaxed pose, seemingly willing to accept God’s gift, and God is a powerful, determined, imposing figure and surrounded and being held up by a flock of angels (and two often debated figures) against a red cape.

Amongst the cherubs witnessing this key moment in Christian mythology is a feminine figure that seems to be significant to the Creator. She is brighter than the others and His arm is around her. Is it Eve, waiting to be born from Adam’s rib? The Virgin Mary? If so, is the cherub to her left, the one with Gods finger on his shoulder, Jesus? Is he turned away because one day he will have to suffer for the sins of his father’s new favorite? And that is surly the Archangel Michael flying below, as if supporting the whole cast. Amongst this heavenly entourage, is that Lucifer, the soon-to-be fallen angel, face half in shadow, grasping the woman’s arm (maybe it is Eve? Or is it both Eve, the sinner, and Mary, the saint, the image of a Universal Woman?) and whispering in her ear? And who is the unhappy-looking, brooding angel in the bottom left? Like any self-respecting Renaissance artist, Michelangelo left many clues, secrets, and mysteries for scholars and art lovers to ponder over for hundreds of years.

One particular message that Michelangelo added to his masterpiece would be noticed only by the 20th century. In the October 10, 1990, issue of the Journal of the American Medical Association, Frank Lynn Meshberger, MD, a gynecologist at St. John's Medical Center in Anderson, Indiana, pointed out that the shroud surrounding God and the angels looks incredibly like a human brain. Indeed, once you see it, it can’t be unseen. As was common for artists of his day, Michelangelo dissected corpses to learn more about human anatomy, and certainly knew what the brain looked like, inside and out. What was the master trying to convey by placing the Creator of the Universe in a giant human brain? Perhaps the real gift he portrayed Adam as accepting was intellect. Or maybe there was a more rebellious message he was trying to convey. Could the devoutly Catholic artist secretly have portrayed God as an imagination in the mind of Adam on the ceiling of one of the holiest places of the Catholic Church? If so, it would have been the greatest example of trolling in the history of mankind.

Another enigma of the painting often pointed out is the fact that Adam has a bellybutton. Why would the first human, born without a mother, have needed a bellybutton? Was this an oversight on the part of the genius or another hint as to his true beliefs? The shadow behind Adam looks remarkably like a female breast, nipple and all. Did Michelangelo have doubts about the divine creation of mankind? Unfortunately, only the artist himself could answer these questions, and he is long dead, leaving us to only speculate and make educated guesses. Some have claimed that, instead of a brain, the form surrounding God is a uterus, the umbilical cord being His arm, reaching out and giving life to Adam.

The angels, even Jesus, don’t look very happy to see Adam. Perhaps they are jealous of the human, or have the foresight to see what kind of trouble His new favorite creation will create. And Adam himself seems not very motivated to make the connection with his creator. His body is relaxed and passive, and he is making the minimal amount of effort to reach out his hand to God, who seems to be fighting a great wind to get to Adam, using all his might. What is this discrepancy meant to convey? That God wants us to come to him? That all it takes is the slightest attempt to make contact with the divine?

Originally the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel was painted blue with gold stars, but in 1508 Pope Julius II commissioned Michelangelo to repaint it. The great artist was wary of taking on such a large project and suspected that he was expected to fail. After he initially turned down the order to paint just the twelve apostles, the Pope relented and gave Michelangelo a free hand to design the ceiling as he wished.

In all, the master painted 460 square meters of frescoes and over 300 figures, portraying the creation, Adam and Eve, and the Great Flood. He also painted the Last Judgement, based on the Book of Revelations, covering the entire wall behind the alter.

As the only true competition for da Vinci to the title “archetypal Renaissance man,” Michelangelo outshined all of his various rivals—inside the Church and out—with this truly world-changing masterpiece, influencing popular and religious culture to this day.

The focal point of the Creation of Adam is the almost touching fingers of the first human and his creator. Michelangelo masterfully painted them as close to making contact as possible, leaving us to wonder whether this the moment just before God touches Adam, giving him life and representing the union of the earthly and the divine, or just after it, representing their separation. Adam is shown in a relaxed pose, seemingly willing to accept God’s gift, and God is a powerful, determined, imposing figure and surrounded and being held up by a flock of angels (and two often debated figures) against a red cape.

Amongst the cherubs witnessing this key moment in Christian mythology is a feminine figure that seems to be significant to the Creator. She is brighter than the others and His arm is around her. Is it Eve, waiting to be born from Adam’s rib? The Virgin Mary? If so, is the cherub to her left, the one with Gods finger on his shoulder, Jesus? Is he turned away because one day he will have to suffer for the sins of his father’s new favorite? And that is surly the Archangel Michael flying below, as if supporting the whole cast. Amongst this heavenly entourage, is that Lucifer, the soon-to-be fallen angel, face half in shadow, grasping the woman’s arm (maybe it is Eve? Or is it both Eve, the sinner, and Mary, the saint, the image of a Universal Woman?) and whispering in her ear? And who is the unhappy-looking, brooding angel in the bottom left? Like any self-respecting Renaissance artist, Michelangelo left many clues, secrets, and mysteries for scholars and art lovers to ponder over for hundreds of years.

One particular message that Michelangelo added to his masterpiece would be noticed only by the 20th century. In the October 10, 1990, issue of the Journal of the American Medical Association, Frank Lynn Meshberger, MD, a gynecologist at St. John's Medical Center in Anderson, Indiana, pointed out that the shroud surrounding God and the angels looks incredibly like a human brain. Indeed, once you see it, it can’t be unseen. As was common for artists of his day, Michelangelo dissected corpses to learn more about human anatomy, and certainly knew what the brain looked like, inside and out. What was the master trying to convey by placing the Creator of the Universe in a giant human brain? Perhaps the real gift he portrayed Adam as accepting was intellect. Or maybe there was a more rebellious message he was trying to convey. Could the devoutly Catholic artist secretly have portrayed God as an imagination in the mind of Adam on the ceiling of one of the holiest places of the Catholic Church? If so, it would have been the greatest example of trolling in the history of mankind.

Another enigma of the painting often pointed out is the fact that Adam has a bellybutton. Why would the first human, born without a mother, have needed a bellybutton? Was this an oversight on the part of the genius or another hint as to his true beliefs? The shadow behind Adam looks remarkably like a female breast, nipple and all. Did Michelangelo have doubts about the divine creation of mankind? Unfortunately, only the artist himself could answer these questions, and he is long dead, leaving us to only speculate and make educated guesses. Some have claimed that, instead of a brain, the form surrounding God is a uterus, the umbilical cord being His arm, reaching out and giving life to Adam.

The angels, even Jesus, don’t look very happy to see Adam. Perhaps they are jealous of the human, or have the foresight to see what kind of trouble His new favorite creation will create. And Adam himself seems not very motivated to make the connection with his creator. His body is relaxed and passive, and he is making the minimal amount of effort to reach out his hand to God, who seems to be fighting a great wind to get to Adam, using all his might. What is this discrepancy meant to convey? That God wants us to come to him? That all it takes is the slightest attempt to make contact with the divine?

Originally the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel was painted blue with gold stars, but in 1508 Pope Julius II commissioned Michelangelo to repaint it. The great artist was wary of taking on such a large project and suspected that he was expected to fail. After he initially turned down the order to paint just the twelve apostles, the Pope relented and gave Michelangelo a free hand to design the ceiling as he wished.

In all, the master painted 460 square meters of frescoes and over 300 figures, portraying the creation, Adam and Eve, and the Great Flood. He also painted the Last Judgement, based on the Book of Revelations, covering the entire wall behind the alter.

As the only true competition for da Vinci to the title “archetypal Renaissance man,” Michelangelo outshined all of his various rivals—inside the Church and out—with this truly world-changing masterpiece, influencing popular and religious culture to this day.

Outside of this, she has almost nothing to mean - Michelangelo, unlike many Renaissance

It's another matter - what did the creation of man itself mean for its time?

The man of Florentine humanism is geometry within clay. Clay can bend, tear, become covered with buboes, fight for trade with Constantinople, can love other clay, can walk on it with his feet. Clay is subject to circumstances, and historically it has not proven itself very well.

Geometry is beautiful and true. She is beautiful and true even when the clay is not ...