In their works, the Pre-Raphaelites

often turned to the theme of the Middle Ages and the early Renaissance — the artists were attracted by the beautiful plots of old stories and legends, the exalted relationships described in them and the exploits of brave knights for the sake of beautiful ladies. However, the visualisation of their paintings is often closer to fantasy than to the realities of distant times. On their canvases, what was real in the past and what was not, we learned from the historical reenactors, showing them famous paintings.

Katya (Kateryna) Liashenko

Reenactor with 11 years of experience. Since 2008 she has been engaged in historical dances, in 2010 she created the Royal Tailor historical costume studio.

Katya and Serhii are participants in living history festivals, reenactments of knightly tournaments, dance events covering the time period from the Middle Ages to the early 20th century.

Serhii Hunkov

has been engaged in historical reenactment since 2015. In 2013, he left his job in IT and began to create armour. In 2018, he retrained and became a carpenter who makes historical furnishings and household items. He founded the Woodandvil project, specializing in the recreation of antique handicrafts and furniture. He is fond of historical European duel fencing.

Why are the Pre-Raphaelite Middle Ages "not real"?

Paintings by the Pre-Raphaelites can only tell us a romanticized vision of the past that existed in the 19th century, but they cannot be used as sources for historical study or reenactment. Some of the artists simply did not strive for historical accuracy, while others made deliberate mistakes for the sake of aesthetics. Substantially, their canvases are characterized by general errors:• anachronisms: clothes, armour and furnishings are taken from different decades and even centuries;

• depicting only the most romantic, beautiful and pretentious things: that’s why the Pre-Raphaelites primarily painted the most visually attractive armour — that of the late 15th — early 16th centuries. At that, knightly vestments and ancient architecture were preserved quite well, whereas the situation is completely different with medieval clothing — it was not at all as attractive as the artists would like. Therefore, the medieval costumes in the paintings are rather "fantasy";

• embellishment: for greater attractiveness, artists supplemented what they saw in historical sources with a lot of decorative elements, such as overlays, embroidery, braid, patterns, as regards outfits.

The wedding of Saint George and Princess Sabra

1857, 36.5×36.5 cm

Differences in costumes and armour in different countries

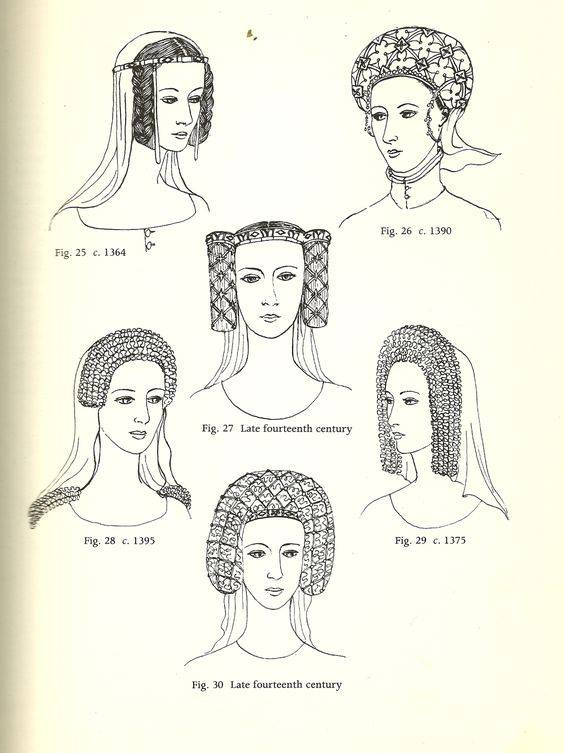

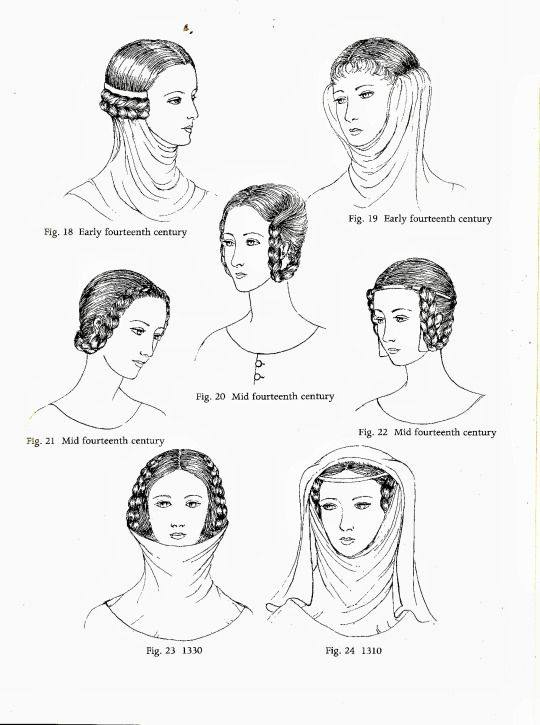

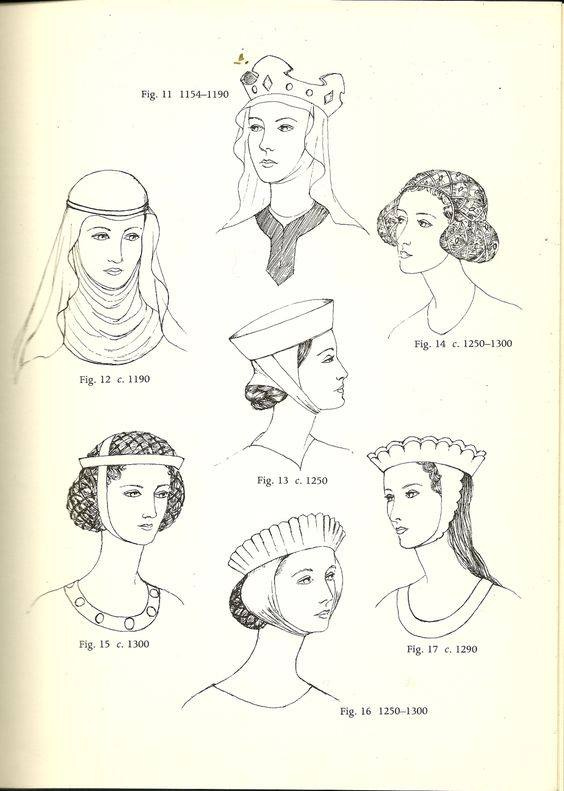

The fashion of the Middle Ages cannot be judged on the basis of the modern map of Europe: in different periods, countries, peoples, regions changed, split up and united, so there were differences in the elements of clothing, accessories, and hats. Moreover, the tone was set by climatic and territorial features, and not by formal borders between countries. These differences become more noticeable by the 15—16th centuries.Armour could be different in different periods in different European regions, there also existed a fashion. The most noticeable difference began in the 15th century, when the European schools of armour were divided into two — the Italian and German schools.

Frederick William Burton. Hellelil and Hildebrand, the Meeting on the Turret Stairs

The Meeting on the Turret Stairs painting was painted by Frederick William Burton; it was influenced by the poem of his friend, the famous celtologist Whitley Stokes. The poem, in turn, was created on the basis of an old Danish ballad. The watercolour drawing depicts the scene of the last one-on-one meeting of the legendary Scandinavian princess Hillelil and her lover, the English prince Hildebrand, who served as her bodyguard, according to the ballad, and later he became her lover and died in battle with her father and brothers.

Hellelil and Hildebrand, The Meeting on the Turret Stairs

1864, 95.5×60.8 cm

Hellelil and Hildebrand is a good example of working with a medieval subject: minimum comments. Thus, Hellelil’s outfit and Hildebrand’s armour are taken from different centuries: the dress is similar to the originals of the early 12th century, and the armour is from the 9—10th centuries, moreover, they are slightly embellished, and the sword is from later times.

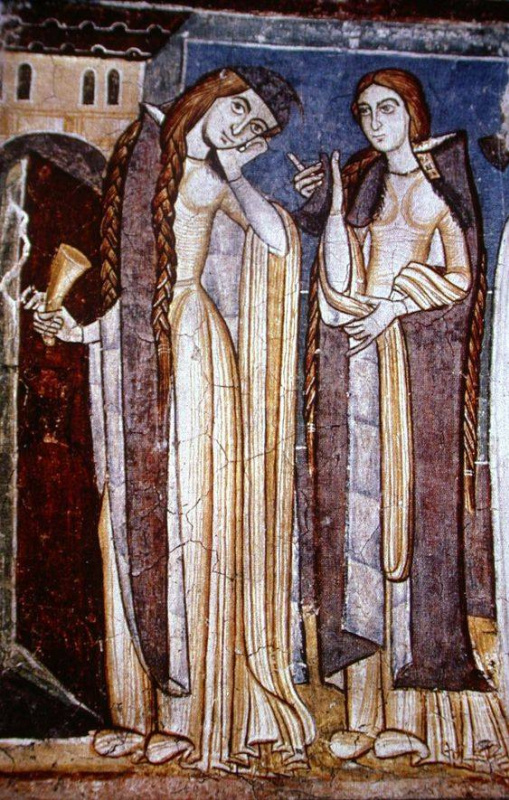

The Hellelil’s dress is lined with fine fur, it is a winter version of the clothing. Whether fabrics of such a deep blue could have existed is impossible to say for sure, because the originals of clothing have not survived, and the colours on medieval pictorial sources changed over time. In addition, different pigments were used to paint the canvas and create paintings. Concerning the hairstyle, in general, braids at that time were the most common way of styling hair. All the little things drawn in the picture are the vision of the artist.

The Hellelil’s dress is lined with fine fur, it is a winter version of the clothing. Whether fabrics of such a deep blue could have existed is impossible to say for sure, because the originals of clothing have not survived, and the colours on medieval pictorial sources changed over time. In addition, different pigments were used to paint the canvas and create paintings. Concerning the hairstyle, in general, braids at that time were the most common way of styling hair. All the little things drawn in the picture are the vision of the artist.

Hildebrand wears a typical full size chain mail armour of the early dark Middle Ages, characteristic of the 10—11th centuries, such armours were worn before the Crusades. There are several things that confuse me in this artwork: helmet, sword and shoes.

On the helmet, we see a bronze nosepiece, which was characteristic of the jarls (nobility) or simply rich warriors. In general, this is not a mistake: the author most likely wanted to show a fairly simple attire, but with high-quality decorative elements. Although it was more logical to depict a simpler version, something similar to a helmet from Gjörmundby.

Concerning the sword: its hilt, embossed leather and repeating patterns on it, rather, correspond to a later period. Moreover, we see a Romanesque type of sword, and it would be appropriate to depict a Carolingian one in the picture.

And lastly, the knight in the picture wears sharp-nosed crackows, which came into fashion later in the 14th century, and before that time round-nosed ones were popular.

On the helmet, we see a bronze nosepiece, which was characteristic of the jarls (nobility) or simply rich warriors. In general, this is not a mistake: the author most likely wanted to show a fairly simple attire, but with high-quality decorative elements. Although it was more logical to depict a simpler version, something similar to a helmet from Gjörmundby.

Concerning the sword: its hilt, embossed leather and repeating patterns on it, rather, correspond to a later period. Moreover, we see a Romanesque type of sword, and it would be appropriate to depict a Carolingian one in the picture.

And lastly, the knight in the picture wears sharp-nosed crackows, which came into fashion later in the 14th century, and before that time round-nosed ones were popular.

John William Waterhouse. Tristan and Isolde with Potion

The Tristan and Isolde with Potion painting is based on the legend of unhappy love, popular in the Middle Ages, a story that came to Europe in a Celtic design. According to the plot, Isolde was supposed to marry King Mark, a feudal lord to whom Tristan was subordinate, but on their way to his domain, the young man and woman accidentally drink a magic potion and fall in love with each other. This very moment is captured on the canvas by Waterhouse.

Tristan and Isolde with the potion

1916, 109.2×81.3 cm

Tristan wears the vestments of the second half of the 15th century, being a full chain mail armour of the German school. It must be said that the Pre-Raphaelites

preferred drawing precisely German armour — in their paintings, others are almost never found.

Isolde’s clothes "lags behind" Tristan’s vestments — his armour corresponds to the second half of the 15th century, and the outfit we see on the girl was worn at the end of the 13th and until the mid-14th century. At the same time, it is quite holistic: we see a bottom dress (this is a cotte or its later version, cote-hardie, you cannot say for sure, since it is not completely visible), over it there is a sideless surcoat trimmed with ermine, which is a sign of the ceremonial dress of a high status lady, and he is wearing a long raincoat — however, I have not seen such fastening options as his, and usually they were not decorated this way.

On Isolde’s head, there is a veil, however, it should be attached to braided hair, a fabric strip or a cap.

On Isolde’s head, there is a veil, however, it should be attached to braided hair, a fabric strip or a cap.

John William Waterhouse. I Am Half-Sick of Shadows, Said the Lady of Shalott

The title of the Waterhouse’s work quotes a line from Alfred Tennyson’s poem, "The Lady of Shallot". The creation of this work by Tennyson was inspired by a legend from the Arthurian cycle, however it has been reworked and acquired a new meaning: the new emphasis was shifted to the forced imprisonment of a beautiful girl in a castle, at that she even cannot look out from the window because of the mysterious spells imposed on her. All her life she only watched the world through the mirror standing next to her, but one day she could not stand it and looked out the window at Lancelot galloping past, which led to her death. Waterhouse referred to different points from the poem three times.

Lady Of Shallotte. "I was chasing shadows"

1915, 100.3×73.7 cm

The dress on the lady of Shallot is absolutely fancy, it cannot be considered from a historical point of view.

A round mirror hangs behind the lady, but in the Middle Ages, such large mirrors did not exist yet, moreover, they were normally convex.

There are oil lamps hanging at the top — I personally am very interested in their availability and use in Europe in the 14—15th centuries, because it is convenient for reenactments. However, although there were oil lamps at that time, they looked completely different, not like the oriental "Aladdin's lamps" depicted on the canvas.

A round mirror hangs behind the lady, but in the Middle Ages, such large mirrors did not exist yet, moreover, they were normally convex.

There are oil lamps hanging at the top — I personally am very interested in their availability and use in Europe in the 14—15th centuries, because it is convenient for reenactments. However, although there were oil lamps at that time, they looked completely different, not like the oriental "Aladdin's lamps" depicted on the canvas.

The famous mirror in the Arnolfini Portrait by Jan van Eyck

John William Waterhouse. A Tale from the Decameron

The Decameron by Giovanni Boccaccio was and remains one of the most famous works of the Renaissance , and on his canvas, John William Waterhouse shows us his version of what was happening in a remote Italian estate, where, according to the plot, ten young people were hiding from the plague. For two weeks in a row, they told each other stories on a variety of topics — and Boccaccio in his book combined these stories in the form of short novellas, and Waterhouse interpreted the goings-on in the country villa in a sublimely romantic style.

The Decameron

1916, 101×159 cm

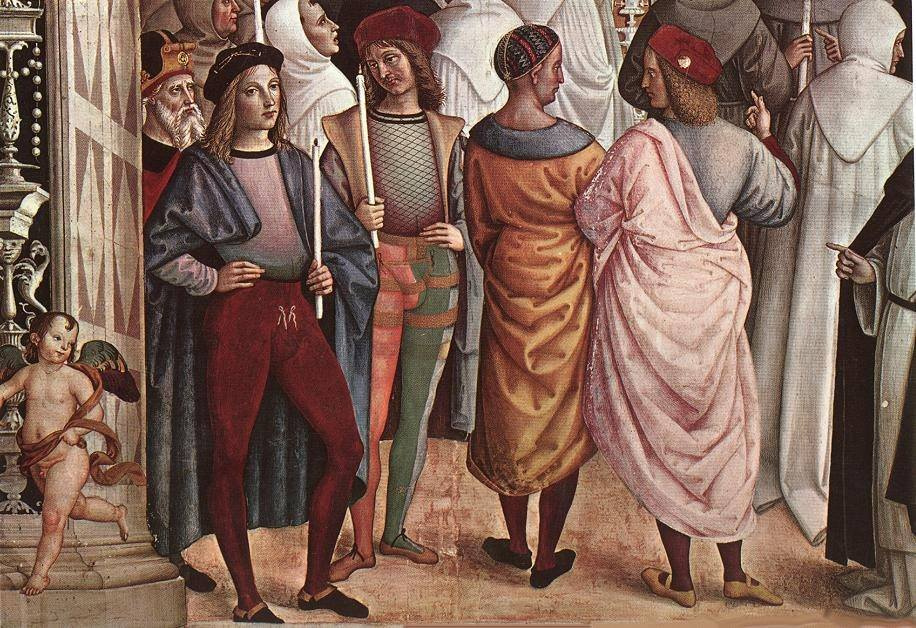

Here, the costumes hint of 15th century Italy, but it’s only a hint, and we mainly see it in men’s clothing. In the foreground, young men have hairstyles and hats in the Italian fashion. One of them wears striped chausses within the same fashion, while the other has a short, tight doublet, with lacing in the front, as well as with slits on the sleeves loved so much by Italians.

However the young ladies wear totally fancy dresses, the dress of the girl on the right looks a bit like the most simple Italian one, but only because of the slits. It is also difficult to find some similarities in hairstyles, although hats in 15th century Italy were not required, they were considered more of a fashionable adornment; ladies mostly weaved complex patterns of their braids, and laid them under hats, turbans or nets.

However the young ladies wear totally fancy dresses, the dress of the girl on the right looks a bit like the most simple Italian one, but only because of the slits. It is also difficult to find some similarities in hairstyles, although hats in 15th century Italy were not required, they were considered more of a fashionable adornment; ladies mostly weaved complex patterns of their braids, and laid them under hats, turbans or nets.

Edmund Blair Leighton. The Accolade

Accolade is the knighting process, which is captured on Leighton’s painting of the same name. There are still debates about the events, which formed the basis of the picture. One of the most beautiful versions says that The Accolade depicts the knighthood of Lancelot by Queen Guinevere.The clothes and armour of the warrior belong to the 10—11th centuries. Chain mails of this type have been known since the 5th century, but this very type is called "hauberk", is tightly fitted to the body — it appeared in the 10th century.

The military cotte is worn on top of the armour — according to legend, it first appeared during the crusades to the Orient, during which the soldiers had to endure the heat, and they began to put long dyed cloths over the chain mail.

But the helmet is completely out of place here. It is an Italian barbute, it belongs to the 15th century. In fact, such helmets were still characteristic of Ancient Rome, but in the 15th century they were "reincarnated" by Italian masters, and began to be made of steel, not bronze.

The traditional women’s outfit of the Middle Ages was as follows: a chainse, on top of which one or two "bliaud" dresses were worn (depending on the occasion, the status of the lady, the season), and a cloak on top. Here, the heroine’s clothes look like bliaud with wide sleeves, but in that era, there was no such cut, fit, puffed sleeves, such a neckline. Bliaud was a very primitive garment made of squares and rectangles. For sure, bliaud could not be white or with such a decoration.

An essential point: the lady is depicted with her hair loose, while in the Middle Ages, a girl with an uncovered head, and even more so with loose hair, was either a saint or a libertine.

The military cotte is worn on top of the armour — according to legend, it first appeared during the crusades to the Orient, during which the soldiers had to endure the heat, and they began to put long dyed cloths over the chain mail.

But the helmet is completely out of place here. It is an Italian barbute, it belongs to the 15th century. In fact, such helmets were still characteristic of Ancient Rome, but in the 15th century they were "reincarnated" by Italian masters, and began to be made of steel, not bronze.

The traditional women’s outfit of the Middle Ages was as follows: a chainse, on top of which one or two "bliaud" dresses were worn (depending on the occasion, the status of the lady, the season), and a cloak on top. Here, the heroine’s clothes look like bliaud with wide sleeves, but in that era, there was no such cut, fit, puffed sleeves, such a neckline. Bliaud was a very primitive garment made of squares and rectangles. For sure, bliaud could not be white or with such a decoration.

An essential point: the lady is depicted with her hair loose, while in the Middle Ages, a girl with an uncovered head, and even more so with loose hair, was either a saint or a libertine.

Edmund Blair Leighton. Defeated

The subject of this picture is simple and clear: a young knight who has failed in battle leaves the battlefield at a knightly tournament. The winner and the jubilant crowd are left behind, but the main subject is clearly separated by a shadow from their sunlit world, he is frustrated and detached from everything that happens.

Edmund Blair Leighton. Defeated

All the knightly vestments are nice, every detail is fine and pleasing to the eye. Maximilian’s advanced tournament armour (named after Emperor Maximilian I) of the 30—35s of the 16th century, very expensive, their cost could be comparable to the cost of several villages. The same armour is depicted on Millais’s Joan of Arc. Most likely they drew from exhibits of museums or private collections, since the detailing is very high quality.

The page’s dress is appropriate for the era and is not at all poor. The only thing that bothers me is that he is holding a sword, which he took with his bare hand for some reason. This blade is the espada ropera, it is more intended for foot combat than for equestrian combat. Moreover, the knight has a spear: it is carried by a servant behind. Then why is there a sword?

In the background we see a tribune: everything is authentic, except for the size of the tents. They’re too big.

The page’s dress is appropriate for the era and is not at all poor. The only thing that bothers me is that he is holding a sword, which he took with his bare hand for some reason. This blade is the espada ropera, it is more intended for foot combat than for equestrian combat. Moreover, the knight has a spear: it is carried by a servant behind. Then why is there a sword?

In the background we see a tribune: everything is authentic, except for the size of the tents. They’re too big.

Edmund Blair Leighton. Call to Arms

In this work, Leighton depicted a young man and a girl leaving the church after their own wedding. Just above them, we can see the parents of the young couple, gazing in horror at how the knight in full armour informs the bridegroom of the impending war and his need to join the battle. This work was the first in a series of large paintings showing different aspects of the life of the knights and their beloved ones (another one was the famous The Accolade), but the most interesting fact is that the artist collected armour and weapons and depicted objects from his own collection.Great work! Very good portrayal of costumes (circa 1530s), accessories, hats and corresponding armour in the Anglo-German fashion (also of the 16th century, most likely the Netherlands). Everything is fine, except for the bride’s dress — it is made in the Italian style of the 15th century, and could only have existed a hundred years earlier. Moreover, her outfit is white, while at that time, only the cheapest unpainted fabric was white, of which linen was sewn. They got married in most beautiful coloured dresses, and the fashion for white appeared after the wedding of Queen Victoria of England in 1840. In addition, the bride is depicted with her hair loose, which was unacceptable, and with a 19th century handbag on her belt.

John Everett Millais. Joan of Arc

In Millais’s portrait, Joan of Arc is knelt, but holding her sword in both hands — the artist captured the moment when the Maid of Orleans hears the voices of the saints encouraging her and calling to fight against the British.

Joan of Arc in prayer

1865, 82×62 cm

The armour here is perfectly drawn, besides, Joan is depicted in a dress, which corresponds to the traditions of the Middle Ages. But the Maid of Orleans lived in France at the beginning of the 15th century, and her armour is German, such armour was popular 150 years later than the events shown.

John Everett Millais. Mariana

Mariana is the heroine of Shakespeare’s play "Measure for Measure", who sailed to her future husband Angelo on a ship, but on her way, she got into a shipwreck, lost her dowry, and was rejected by her groom. Because of this, the girl had to lead a lonely life, spending days in longing for her lover. In the end, they still got married, but before that, Mariana spent a lot of time alone — Tennyson wrote his poem about this period of her life, and Millais accompanied his picture with his verse. His Mariana is a woman suffering from the abandonment of the world, the power of compelling circumstances and her own unspent sexual desire.

Mariana

1851, 59.7×49.5 cm

The ottoman with red upholstery, from which Mariana just got up, does not match the rest of the interior, it is taken from the 19th century.

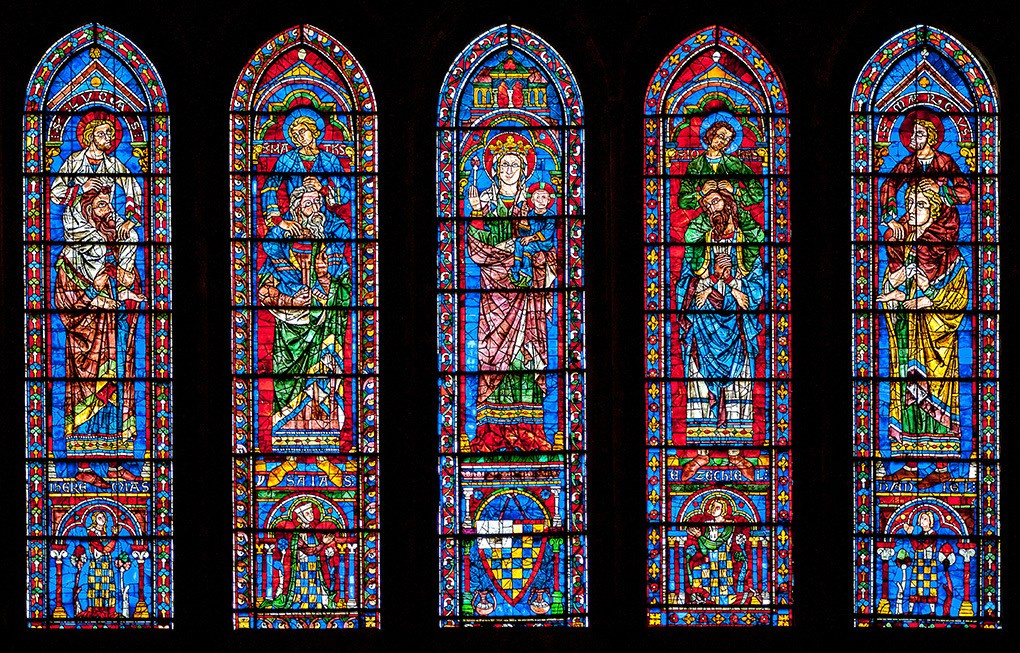

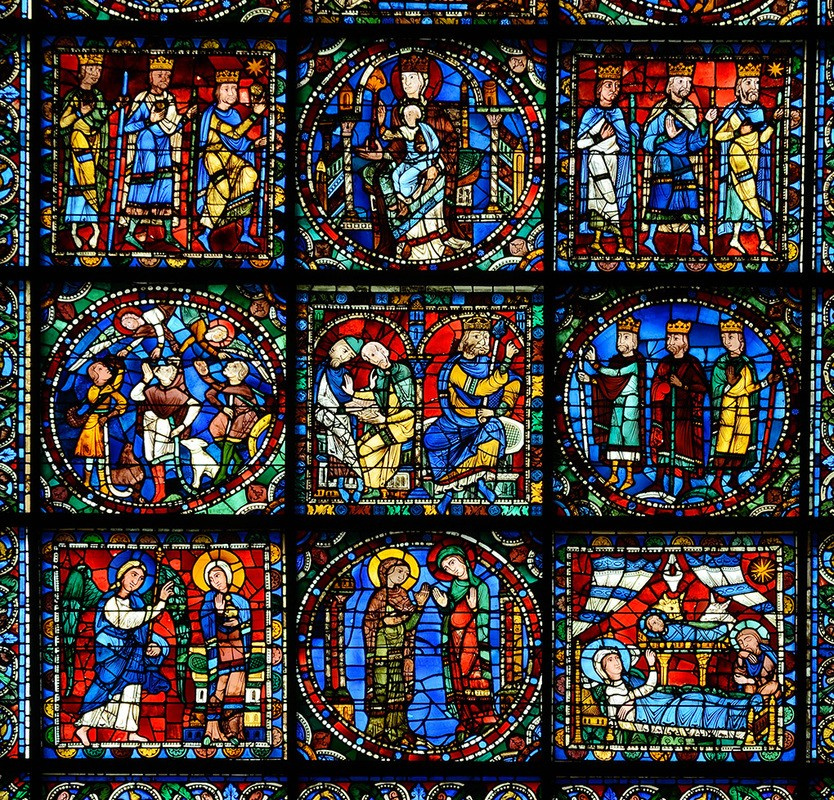

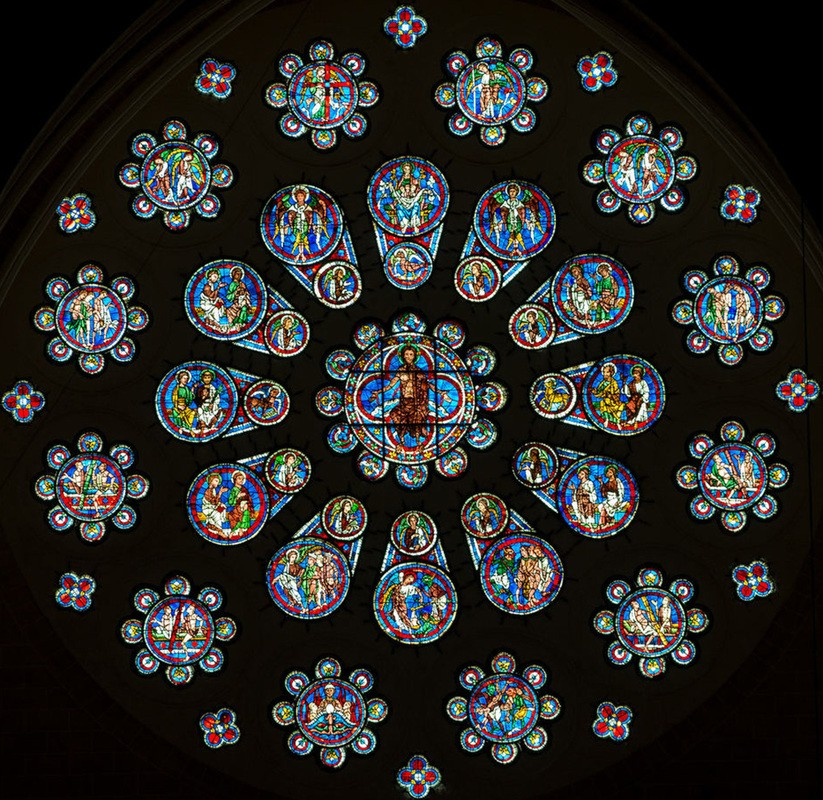

Glass windows began to spread from the end of the 14th century. Before that, instead of glasses, people used cloth, a bullish cloudy bladder or cloth. On the windows, we see stained glass, one of them depicts the knight’s coat of arms and motto. In fact, mottos were used to decorate fireplaces, furniture, and you’d never find such images on windows in medieval miniatures.

Mariana herself wears a classic cote-hardie dress, which was worn in the 14—15th centuries in Europe.

Glass windows began to spread from the end of the 14th century. Before that, instead of glasses, people used cloth, a bullish cloudy bladder or cloth. On the windows, we see stained glass, one of them depicts the knight’s coat of arms and motto. In fact, mottos were used to decorate fireplaces, furniture, and you’d never find such images on windows in medieval miniatures.

Mariana herself wears a classic cote-hardie dress, which was worn in the 14—15th centuries in Europe.

"Millais, like his Pre-Raphaelite friends, chose literary subjects to talk about modernity. These three artists pretty much shook up Victorian society, tightened into a set of rules and decency like in a tight corset. In a literal sense, by the way, corsets also began to crack at the seams: in the paintings of the Pre-Raphaelites

, women appear without this detail of the wardrobe at all and with loose hair — a dress code permissible only in the matrimonial bedroom, but certainly not in the halls of the Royal Academy…" — from the description of the painting in Arthive.

John Everett Millais. The Ransom

In The Ransom, we see an agitated father giving jewellery to certain men in exchange for his daughters. We do not know the details of what is happening, however, based on the plot of the tapestry hanging behind the characters, it is suggested that the father did not watch his children properly, and they got kidnapped.

The ransom

1862, 129×114 cm

The men’s suits correspond to the fashion of the 16th and 17th centuries here. On the left, the young man in a striped suit is dressed according to the common European fashion of the mid-16th century (doublet, short chausses and stockings), the man in armour has a typical headdress of England in the 40s of the 16th century, whereas the hero of the picture in a light suit on the right is dressed according to the fashion of the 20s of the 17th century (tunics, breeches, stockings). The girls' outfits are rather a kind of invented composite image of the suits of the 15—16th centuries, because at that time there were no separate different clothes for children, first of all, such short dresses. Children’s clothing as such only appeared in the 19th century.

The armour is typical of the 16th century, probably German fashion. Usually, in such vestments, artists captured rich people — lords and kings.

John Everett Millais. Isabella

The painting is inspired by John Keats' Isabella and the Pot of Basil based on the novella from The Decameron by Giovanni Boccaccio. Its main character is a girl named Isabella, whose evil brothers killed her beloved Lorenzo, but she found his body and hid his head in a pot of basil.On the canvas, we can see the moment describing lovers in Keats' poem:

"They could not sit at meals but feel how well

It soothed each to be the other by…"

The work reflects the bad temper of the brothers of the main character: one of them angrily kicks the hunting dog.

For Isabella, as for many other paintings, artist’s family and friends posed, but in this regard it is most interesting because it depicts three members of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood: William Michael Rossetti as Lorenzo, Frederick George Stevens as one of Isabella’s two brothers (with glass in hand), and in the background on the right, we can see Dante Gabriel Rossetti.

Lorenzo and Isabella

1849, 103×142.8 cm

On this canvas, as well as on the other painting by Millais, Mariana, furniture of the 19th century is present. Here it is the chair in the green cover on which Isabella’s elder brother sits.

On the other hand, everything is fine here with costumes, both for men and women — they are holistic and correspond to one period and region — this is Italy of the 15th century. On the foreground girl (Isabella), we can see a very distinctive dress and a hairstyle called the Italian braid. The man on the left (Isabella's elder brother kicking the dog) wears an Italian farsetto doublet and tight-fitting chausses, which were popular throughout Europe during the Renaissance . The young man who sits behind him is wearing a giorno cape worn only in Italy, and a hat in Italian fashion.

Note that the heroes of the picture do not use cutlery, although spoons and one-tooth forks were already in use then. Perhaps only light snacks were served so that people would refresh themselves after the hunt — in the picture we see two hunting dogs and a falcon.

On the other hand, everything is fine here with costumes, both for men and women — they are holistic and correspond to one period and region — this is Italy of the 15th century. On the foreground girl (Isabella), we can see a very distinctive dress and a hairstyle called the Italian braid. The man on the left (Isabella's elder brother kicking the dog) wears an Italian farsetto doublet and tight-fitting chausses, which were popular throughout Europe during the Renaissance . The young man who sits behind him is wearing a giorno cape worn only in Italy, and a hat in Italian fashion.

Note that the heroes of the picture do not use cutlery, although spoons and one-tooth forks were already in use then. Perhaps only light snacks were served so that people would refresh themselves after the hunt — in the picture we see two hunting dogs and a falcon.

Renaissance

women’s fashion on a fragment of the fresco by Domenico Ghirlandaio from the Saint Francis cycle

How it was in the Middle Ages

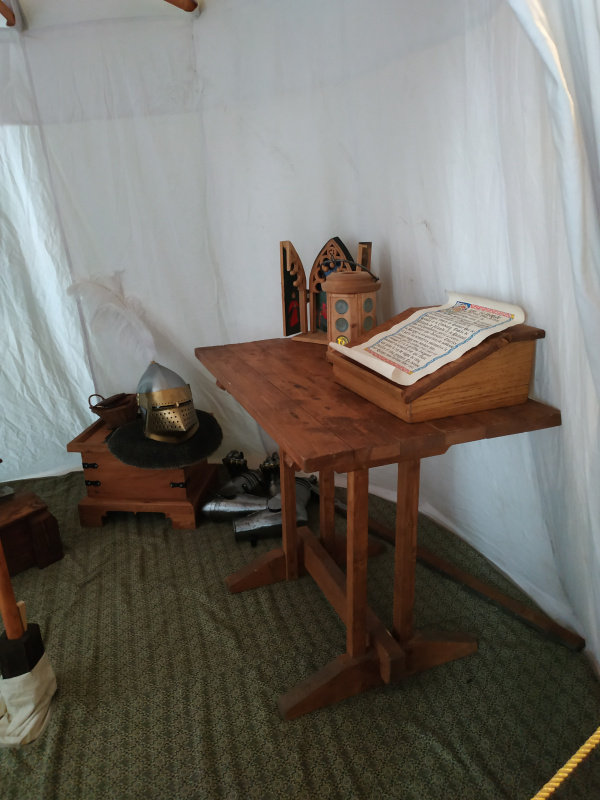

Therefore, there is no everyday "truth" in the pictures by the Pre-Raphaelites , and filmmakers should not bearthem in mind, making historical pictures. Details about the life and customs of distant times could be found, for example, in the Bohdan and Varvara Khanenko Museum of Art during a special thematic week. The "Middle Ages. Living history" program was developed by a team of the cultural institution together with historical reenactors Serhii Hunkov and Kateryna Liashenko and was timed to coincide with the International Museum Day.Visitors could explore the knight’s tent of the 14th century reconstructed by Katya and Serhii, weapons and armour, the outfit of a knight and lady of the 14—16th centuries, their bed and other furniture, and the most enthusiastic visitors went through the "Seekers. Middle Ages" quest.

As part of this week’s events, the museum’s guests learned about the realities of the life of knights and ladies and about the insights and difficulties of historical reenactment. What is it like to be engaged in the reconstruction of a bygone epoch and to collect knowledge about what it really was, bit by bit?