From time to time, in glossy magazines, on LiveJournal, on Facebook, on some pseudo art websites, we come across surprisingly similar "touching" stories from the lives of great people: about endless bouquets of flowers ordered by the long-dead Mayakovsky, about the sister of Faina Ranevskaya, who charmed the Soviet butcher, about the "million scarlet roses" bought by Pirosmani for a French actress, or about Albrecht Dürer, who painted his brother’s hands.

Flowers from Mayakovsky are a refuted fake, the anecdotes around Ranevskaya seem to be indestructible, Pirosmani’s roses were, of course, not a million, but several dozen bouquets, but at least they really were, whereas the story of the "praying hands" is quite worthy of analysis. Despite the dubious literary style and no less dubious plausibility, people like the story for some reason (and, therefore, it is replicated over and over again). Let’s try to analyse how much authenticity is in this "true story". And, since you first have to read it, stock up on handkerchiefs and watch your blood sugar, because the percentage of sugary and sentimentality is dangerously high in the text.

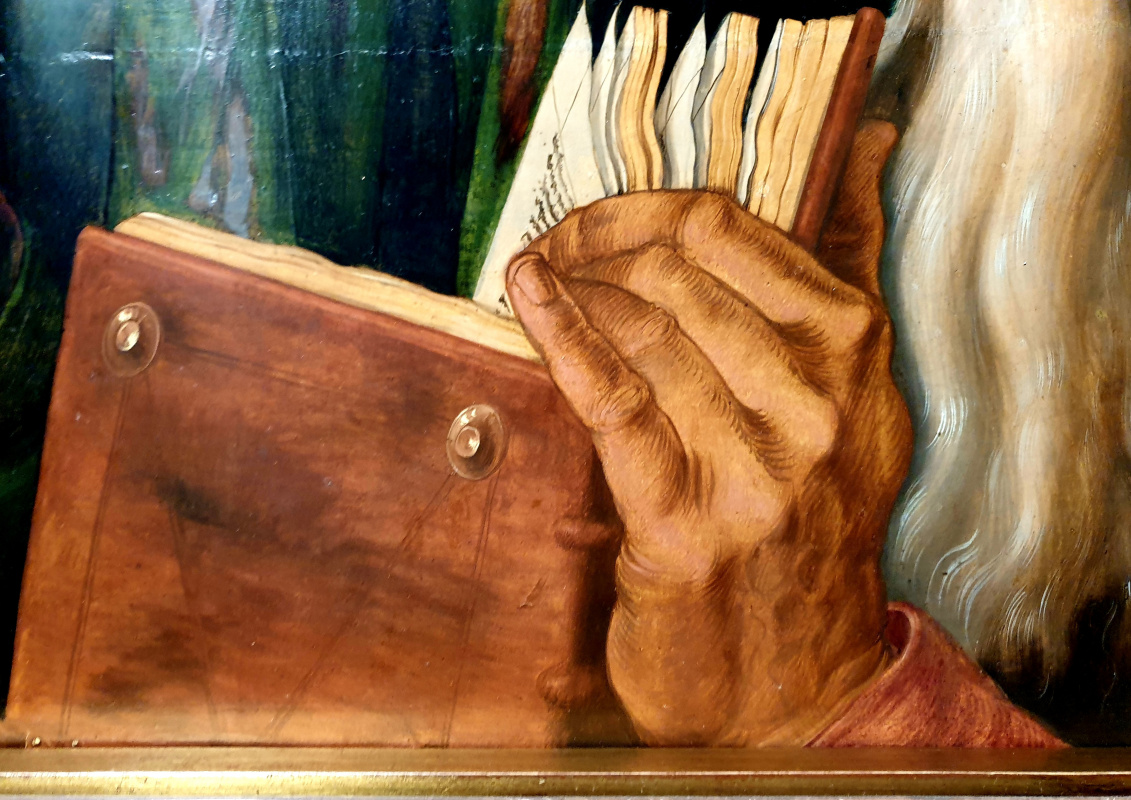

The twelve-year old Jesus teaching in the temple

1494, 45×62 cm

"Many people know the Hands painting by Albrecht Dürer. But few people know the history of its creation. I think that anyone who does not know Dürer will remember this story for his/her life. In the 15th century, a family with eighteen children lived in a small village near Nuremberg. Eighteen! To support such a large family, the father, a goldsmith, worked eighteen hours a day. He worked in a jewellery workshop, but also took on any paid job. Despite the almost hopeless situation, two children had a dream. They wanted to develop their art talent, but they knew that their father would not be able to send any of them to study at the Academy in Nuremberg. After much nightly discussion, the two boys made an agreement with each other. They decided to flip a coin. The loser would go to work in the mines and pay for his brother’s education. And then, when the brother finishes his studies, he would pay for his brother, who worked in the mine, by selling his work, and if necessary, also working in the mines. They threw a coin on Sunday morning after church. Albrecht Dürer won and went to Nuremberg. Albert went to work in hazardous mines, and he paid for his brother’s education for four years, whose work at the Academy immediately became a sensation. Albrecht’s engravings, woodcuts and paintings surpassed even the work of many of his professors. By the time he graduated, he had already started earning good sums for his work. When the young artist returned to his village, the Dürer family hosted a festive dinner on the lawn to celebrate Albrecht’s triumphant return. After a long and unforgettable dinner with lots of music and laughter, Albrecht got up from his place of honour at the head of the table to raise a toast to his beloved brother, who had sacrificed for so many years to fulfil Albrecht’s dream. At the end of his speech, he said: "Now, Albert, my blessed brother, your turn has come. Now you can go to Nuremberg for your dream and I will take care of you."

Everyone turned expectantly to Albert, who was sitting at the other end of the table. Tears streamed down his pale face, he shook his head, sobbed and repeated: "No… no… no… no". Finally he got up and wiped away his tears. He looked at the faces of the people he loved so much, and then, raising his hands to his face, said softly: "No, brother. I cannot go to Nuremberg. It’s too late for me. Look! Look what those four years in the mines have done to my hands! The bones on each finger were broken at least once, and recently I got arthritis in my right hand, so that I can’t even hold a glass while toast, so I can’t draw beautiful lines on parchment or canvas with a pencil or brush any more. No, brother, it’s too late for me." More than 450 years have passed. Now hundreds of portraits, pen or silver pencil drawings, watercolours, charcoal drawings, woodcuts and copper prints hang in every great museum in the world. You are most likely familiar with at least one work by Albrecht Dürer. Maybe you also have a reproduction of one of his works hanging in your home or office.

To pay kind of tribute to Albert for all his sacrifice, Albrecht painted his brother’s hardened hands pointing towards the sky. He called his powerful painting very simply: "Hands". But the whole world almost immediately opened their hearts to this masterpiece and called this painting "Praying Hands".

Everyone turned expectantly to Albert, who was sitting at the other end of the table. Tears streamed down his pale face, he shook his head, sobbed and repeated: "No… no… no… no". Finally he got up and wiped away his tears. He looked at the faces of the people he loved so much, and then, raising his hands to his face, said softly: "No, brother. I cannot go to Nuremberg. It’s too late for me. Look! Look what those four years in the mines have done to my hands! The bones on each finger were broken at least once, and recently I got arthritis in my right hand, so that I can’t even hold a glass while toast, so I can’t draw beautiful lines on parchment or canvas with a pencil or brush any more. No, brother, it’s too late for me." More than 450 years have passed. Now hundreds of portraits, pen or silver pencil drawings, watercolours, charcoal drawings, woodcuts and copper prints hang in every great museum in the world. You are most likely familiar with at least one work by Albrecht Dürer. Maybe you also have a reproduction of one of his works hanging in your home or office.

To pay kind of tribute to Albert for all his sacrifice, Albrecht painted his brother’s hardened hands pointing towards the sky. He called his powerful painting very simply: "Hands". But the whole world almost immediately opened their hearts to this masterpiece and called this painting "Praying Hands".

And now, together with those who were able to finish reading this, we will test this story’s strength.

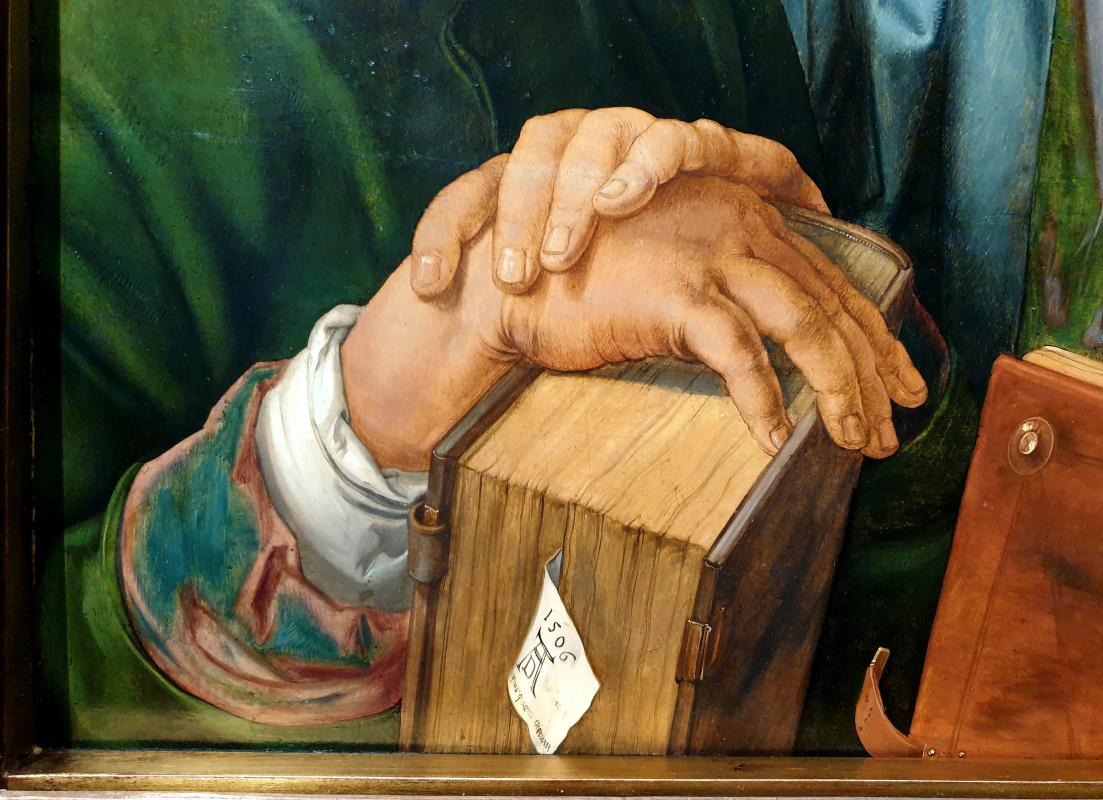

Self-portrait with a sketch of the arms and cushion (front side of sheet)

1493, 27.8×20.2 cm

So: "In the 15th century" is true, but "…in a small village near Nuremberg" is a lie.

The Dürer family lived right in Nuremberg. We know it from the artist himself, who kindly left us his autobiography, part of which says about his father, also Albrecht Dürer: "Then Albrecht Dürer, my dear father, came to Germany; he spent a long time in the Netherlands with great artists and finally came here to Nuremberg, in the year 1455 from the birth of Christ on the day of St. Eligius [25 June]".

The information about the huge "family with eighteen children… Eighteen!" is also incorrect in this formulation.

The Dürer family actually had 18 children, but they never had 18 children at the same time.

Because they never lived long. We also know about this from the Albrecht Dürer's autobiography, the younger, and according to the notes of Albrecht Dürer, the elder, who described the appearance of each baby in detail in his diary.

The Dürer family lived right in Nuremberg. We know it from the artist himself, who kindly left us his autobiography, part of which says about his father, also Albrecht Dürer: "Then Albrecht Dürer, my dear father, came to Germany; he spent a long time in the Netherlands with great artists and finally came here to Nuremberg, in the year 1455 from the birth of Christ on the day of St. Eligius [25 June]".

The information about the huge "family with eighteen children… Eighteen!" is also incorrect in this formulation.

The Dürer family actually had 18 children, but they never had 18 children at the same time.

Because they never lived long. We also know about this from the Albrecht Dürer's autobiography, the younger, and according to the notes of Albrecht Dürer, the elder, who described the appearance of each baby in detail in his diary.

Crying angel (sketch)

1521, 21×17 cm

Only three Dürer boys survived to a fair age, of which Albrecht was the eldest: "All these my brothers and sisters, the children of my dear father, died, some in childhood, others when they grew up. Only we, three brothers, are still alive, as long as God pleases, namely, I, Albrecht, and my brother Endres, as well as my brother Hans, the third of my father’s children to bear this name."

Now let’s talk about the poverty of the Dürer family.

The adoration of the Magi

1504, 99×113.5 cm

"To support such a large family, my father, a goldsmith, worked eighteen hours a day. He worked in a jewellery workshop, but also took on any paid job." We have already understood that the family was not that big at all. But Albrecht Dürer Sr. worked a lot really, like any diligent craftsman of his time. All daylight long, no doubt. Did he take on "any paid job" other than jewellery? It is likely that he took up engraving. Drawings. However, he definitely didn’t, say, dig up vegetable gardens. Because a goldsmith protects one’s hands. And in Nuremberg, he certainly found work for himself. And let the author think, what could a goldsmith from the cited story do 18 hours a day in a "small village near Nuremberg" (probably about thirty yards).

Follow on the text. "Despite the almost hopeless situation, two children had a dream. They wanted to develop their art talent, but they knew that their father would not be able to send any of them to study at the Academy in Nuremberg" — this fragment is totally fine, absolutely. We can already guess that the position of father Dürer was not hopeless. Looking ahead, I inform you that not two brothers should have had the dream, but three of them — all three surviving sons of Albrecht Sr. found themselves in art. Dad did not need to send the children to Nuremberg, they already lived in it.

While he could send them to the Academy of Arts only through a time machine — there was no Academy of Arts in Nuremberg of 15th century.

Although the Nuremberg Academy is the oldest in Germany, it was not founded until 1662. But, strictly speaking, for the initial training of boys, no Academy was needed — their father, Albrecht Dürer Sr. was an excellent drawer (and it could not be otherwise — goldsmiths developed their sketches themselves) and he could teach his children everything related to graphics himself.

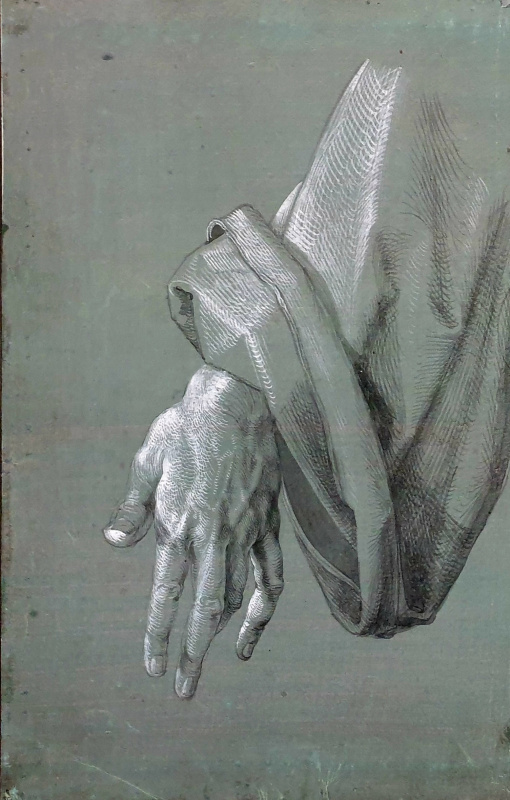

By the way, a self-portrait of Albrecht Dürer Sr., created by him in 1486, follows.

While he could send them to the Academy of Arts only through a time machine — there was no Academy of Arts in Nuremberg of 15th century.

Although the Nuremberg Academy is the oldest in Germany, it was not founded until 1662. But, strictly speaking, for the initial training of boys, no Academy was needed — their father, Albrecht Dürer Sr. was an excellent drawer (and it could not be otherwise — goldsmiths developed their sketches themselves) and he could teach his children everything related to graphics himself.

By the way, a self-portrait of Albrecht Dürer Sr., created by him in 1486, follows.

Albrecht Dürer Senior. Self-portrait (1486)

The next statement brings us closer to the climax. "After much nightly discussion, the two boys made an agreement with each other. They decided to flip a coin. The loser would go to work in the mines and pay for his brother’s education" — it may well be that Albrecht argued with any of his surviving brothers about something and even threw a coin. But definitely, it was not about studying at the Academy, which did not yet exist. And if one of the surviving sons decided to go to impair his hands in the mine, dad Albrecht Dürer Sr. would take a rod and explain him well why the jeweller’s children should not do this. And no juvenile justice would have hindered him.

Actually, all the boys were supposed to become jewellers.

After all, professions at that time were usually hereditary — blacksmiths taught their sons to work with iron, weavers from childhood put their heirs at their machine, and father Dürer hoped that the eldest of the surviving sons would become an excellent jeweller. But he wanted to become a painter: "my father found particular comfort in me, for he saw that I was diligent in my studies. So my father sent me to school, and when I learned to read and write, he took me out of school and began to teach me the craft of a goldsmith. And when I had already learned to work purely, I developed a greater desire for painting than for goldsmithing. I told my father about this, but he was not much happy, as he was sorry for the wasted time that I had spent learning goldsmithing".

After all, professions at that time were usually hereditary — blacksmiths taught their sons to work with iron, weavers from childhood put their heirs at their machine, and father Dürer hoped that the eldest of the surviving sons would become an excellent jeweller. But he wanted to become a painter: "my father found particular comfort in me, for he saw that I was diligent in my studies. So my father sent me to school, and when I learned to read and write, he took me out of school and began to teach me the craft of a goldsmith. And when I had already learned to work purely, I developed a greater desire for painting than for goldsmithing. I told my father about this, but he was not much happy, as he was sorry for the wasted time that I had spent learning goldsmithing".

Double Goblet (1526) A sketch of a piece of jewellery made by Dürer Jr. in his adulthood.

As you can see, the story of his brother’s sacrifice is crumbling like a house of cards, but we shall continue: "Albrecht Dürer won and went to Nuremberg. Albert went to work in hazardous mines, and he paid for his brother’s education for four years, whose work at the Academy immediately became a sensation."

However, Albrecht and Albert are like Alexander, Alex, Alejandro — variants of the same name.

Of course, Dürer's dad and mom gave their children the same names (they had three Hanses), but they usually waited for the previous bearer of the name to die. And, as you remember, of the sons there remained "I, Albrecht, and my brother Endres, as well as my brother Hans".

However, Albrecht and Albert are like Alexander, Alex, Alejandro — variants of the same name.

Of course, Dürer's dad and mom gave their children the same names (they had three Hanses), but they usually waited for the previous bearer of the name to die. And, as you remember, of the sons there remained "I, Albrecht, and my brother Endres, as well as my brother Hans".

"… whose work at the Academy immediately became a sensation. Albrecht’s engravings, woodcuts and paintings surpassed even the work of many of his professors… " while the Academy is not founded, our Albrecht Dürer has to study in a simple large workshop.

There were no "many professors" there, but there was Michael Wolgemut, a quite famous artist of that time, although now he is half-forgotten.

There were no "many professors" there, but there was Michael Wolgemut, a quite famous artist of that time, although now he is half-forgotten.

"…My father agreed to send me as an apprentice to Michael Wolgemut so that I served him for three years. At that time God gave me enough diligence, so I studied well. But I had to endure a lot from this apprenticeship." Alas, there were no special sensations. He studied regularly, improved his drawing, mastered painting and tolerated the teasing from hooligan apprentices, because he was not one of eighteen children from a "small miners' village", but a gentle spoiled boy, his father’s favourite. Now about "engravings and woodcuts". Dürer surely engaged in "woodcuts" in his apprenticeship, in Germany it was the most popular type of engraving at that time, but he would start engraving

on metal later.

"By the time he graduated, he had already started earning good sums for his work" — he certainly earned something by the end of his apprenticeship, but in his "wandering" (a mandatory stage of apprentice training in many workshops), most likely, he was self-sufficient himself. Moreover, Albrecht Sr. (who was a well-to-do man, contrary to the quoted text) certainly gave him some money to start his journey.

"When the young artist returned to his village, the Dürer family hosted a festive dinner on the lawn to celebrate Albrecht’s triumphant return" — when not so young (he wandered for 4 years) Albrecht Dürer returned to Nuremberg, perhaps his family really had a festive dinner on a lawn… Along with the engagement. Because Albrecht Jr., who already worked successfully in a printing house in Basel, might have lived more outside his home, but in 1493, Albrecht Sr. decided it was time to marry the boy and arranged with his friend the coppersmith Hans Frey about his 14-year-old daughter Agnes Frey.

"When the young artist returned to his village, the Dürer family hosted a festive dinner on the lawn to celebrate Albrecht’s triumphant return" — when not so young (he wandered for 4 years) Albrecht Dürer returned to Nuremberg, perhaps his family really had a festive dinner on a lawn… Along with the engagement. Because Albrecht Jr., who already worked successfully in a printing house in Basel, might have lived more outside his home, but in 1493, Albrecht Sr. decided it was time to marry the boy and arranged with his friend the coppersmith Hans Frey about his 14-year-old daughter Agnes Frey.

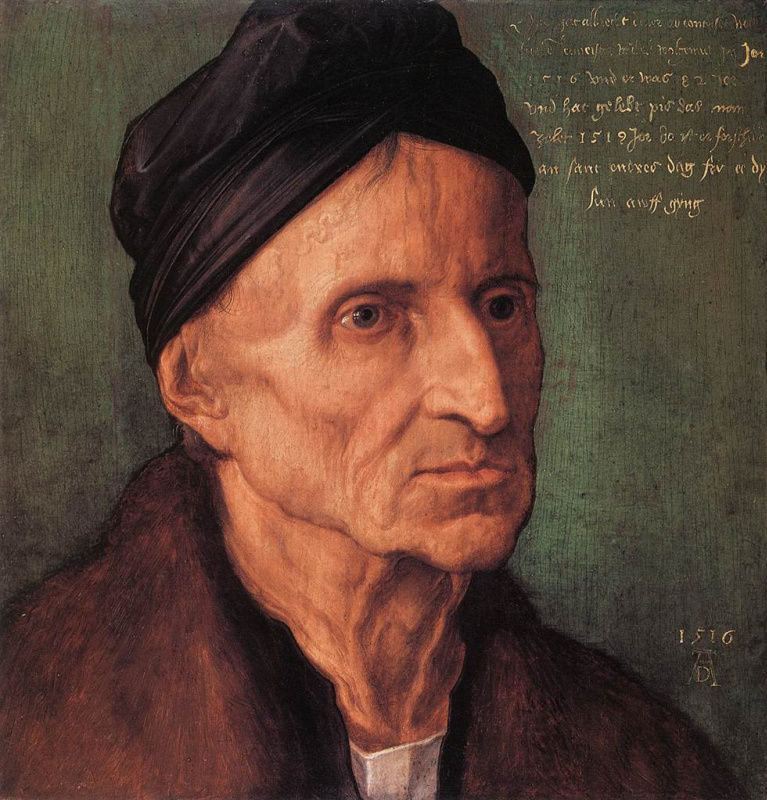

By the way, the girl came with a nice dowry of 200 guilders. Confirming his obedience to his father’s will, Albrecht Jr. sent home a "groom's" self-portrait with the caption "My affairs follow the course allotted to them on high", and in 1494 he returned to Nuremberg.

Self-Portrait with a Thistle

1493, 56×44 cm

"After a long and unforgettable dinner with lots of music and laughter, Albrecht got up from his place of honour at the head of the table to raise a toast to his beloved brother, who had sacrificed for so many years to fulfil Albrecht’s dream. At the end of his speech, he said: ‘Now, Albert, my blessed brother, your turn has come. Now you can go to Nuremberg for your dream and I will take care of you' " — we have already come to terms with the fact that Dürer could not say anything like this to his brother Albert, as well as we do not know what he said after the hypothetical dinner to his younger brothers Enders (born in 1484) and Hans (whom he hardly knew because he was born in 1490).

Moreover, we know for sure from his correspondence that Albrecht helped his brothers multiple times.

"Tell my mother to talk to Wolgemut about my brother, if he can give him a job until I get back, or arrange him with someone else so that he can support himself. I would gladly take him with me to Venice, it would be useful for me and him also for learning the language. But she is afraid that the sky would fall on him. I ask you to look after him yourself, the hope for women is bad. Talk to the boy, as you can, so that he learns and behaves well until I return, and would not be a burden to his mother. I would not be lost alone, but it is too difficult for me to support many. For no one throws away their money" (from Dürer's letter to Wilibald Pirkheimer).

Moreover, we know for sure from his correspondence that Albrecht helped his brothers multiple times.

"Tell my mother to talk to Wolgemut about my brother, if he can give him a job until I get back, or arrange him with someone else so that he can support himself. I would gladly take him with me to Venice, it would be useful for me and him also for learning the language. But she is afraid that the sky would fall on him. I ask you to look after him yourself, the hope for women is bad. Talk to the boy, as you can, so that he learns and behaves well until I return, and would not be a burden to his mother. I would not be lost alone, but it is too difficult for me to support many. For no one throws away their money" (from Dürer's letter to Wilibald Pirkheimer).

We will not re-quote the entire episode with the response speech of the non-existent brother, but simply put it in a folder labelled "sentimental lies".

"More than 450 years have passed" — so far, more than 500 have passed since 1494.

"Now hundreds of portraits, pen or silver pencil drawings, watercolours, charcoal drawings, woodcuts and copper prints hang in every great museum in the world. You are most likely familiar with at least one work by Albrecht Dürer. Maybe you also have a reproduction of one of his works hanging in your home or office" — well, finally, the absolute truth. However, it does not last long.

"More than 450 years have passed" — so far, more than 500 have passed since 1494.

"Now hundreds of portraits, pen or silver pencil drawings, watercolours, charcoal drawings, woodcuts and copper prints hang in every great museum in the world. You are most likely familiar with at least one work by Albrecht Dürer. Maybe you also have a reproduction of one of his works hanging in your home or office" — well, finally, the absolute truth. However, it does not last long.

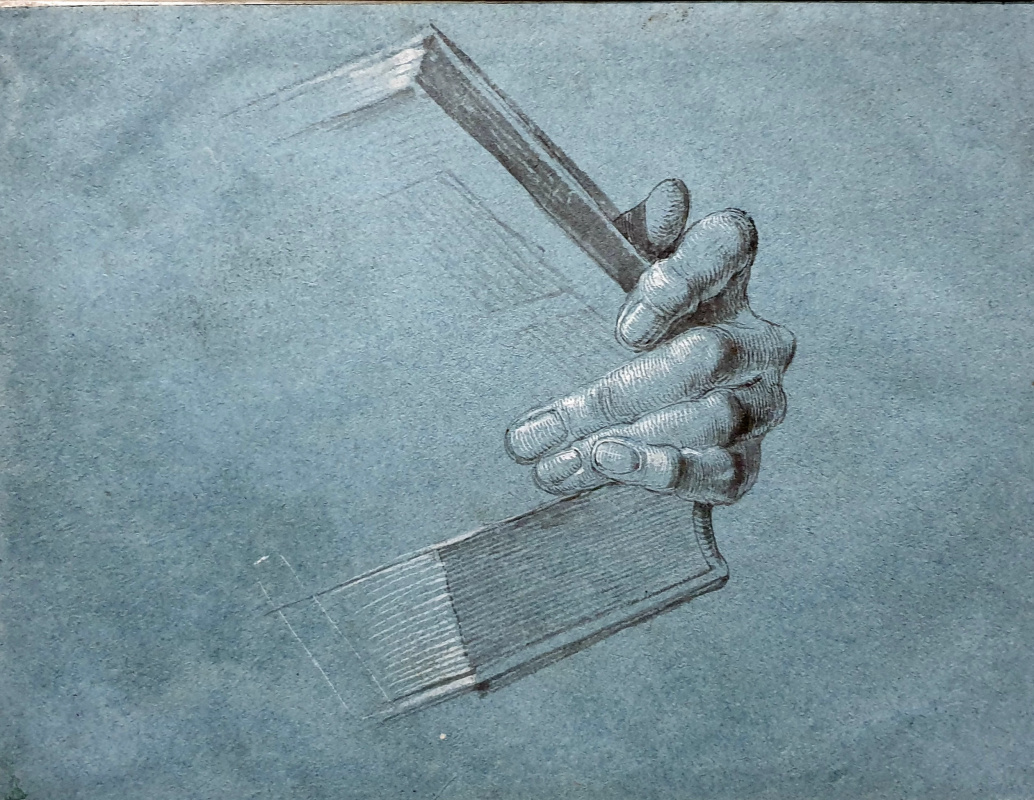

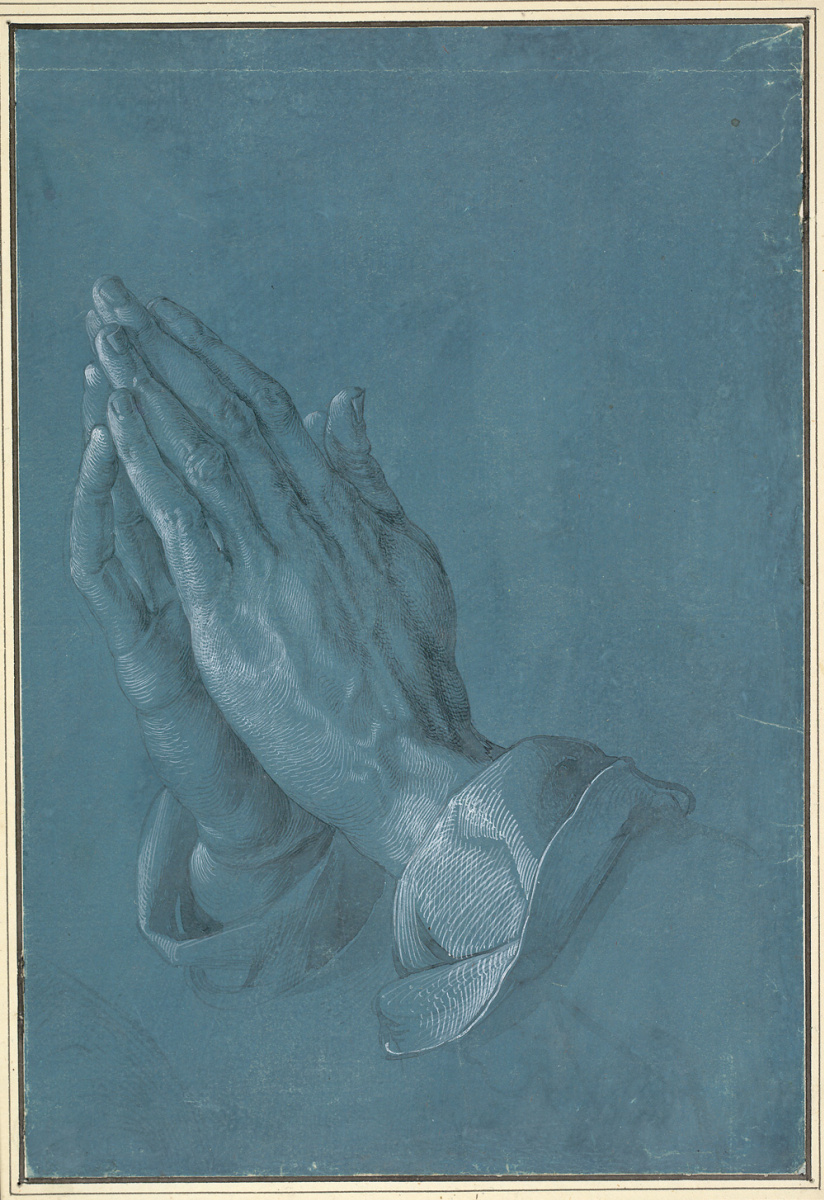

Praying Hands (Hands of the Apostle)

1508, 29.1×19.7 cm

"To pay kind of tribute to Albert for all his sacrifice, Albrecht painted his brother’s hardened hands pointing towards the sky. He called his powerful painting very simply: ‘Hands'. But the whole world almost immediately opened their hearts to this masterpiece and called this painting ‘Praying Hands'." — most art critics believe that in 1508, while making drawings for the Geller’s Altar, Dürer sat down and drew on tinted paper those hands that he drew the most often — his own hands.

The Heller Altar (The Altar Of The Assumption Of Mary). Reconstruction

1500-th

, 190×260 cm

There is also an assumption that the Praying Hands is part of the artist’s portfolio, a careful drawing made by him to demonstrate his talent to customers. It was established that he drew his right hand from the left, reflected in the mirror. As you can see, they do not look like miner’s hands. These are beautiful, long-fingered, well-cared hands of a person who has never done rough work, the curvature of the little finger is the same as in other self-portraits of the artist.

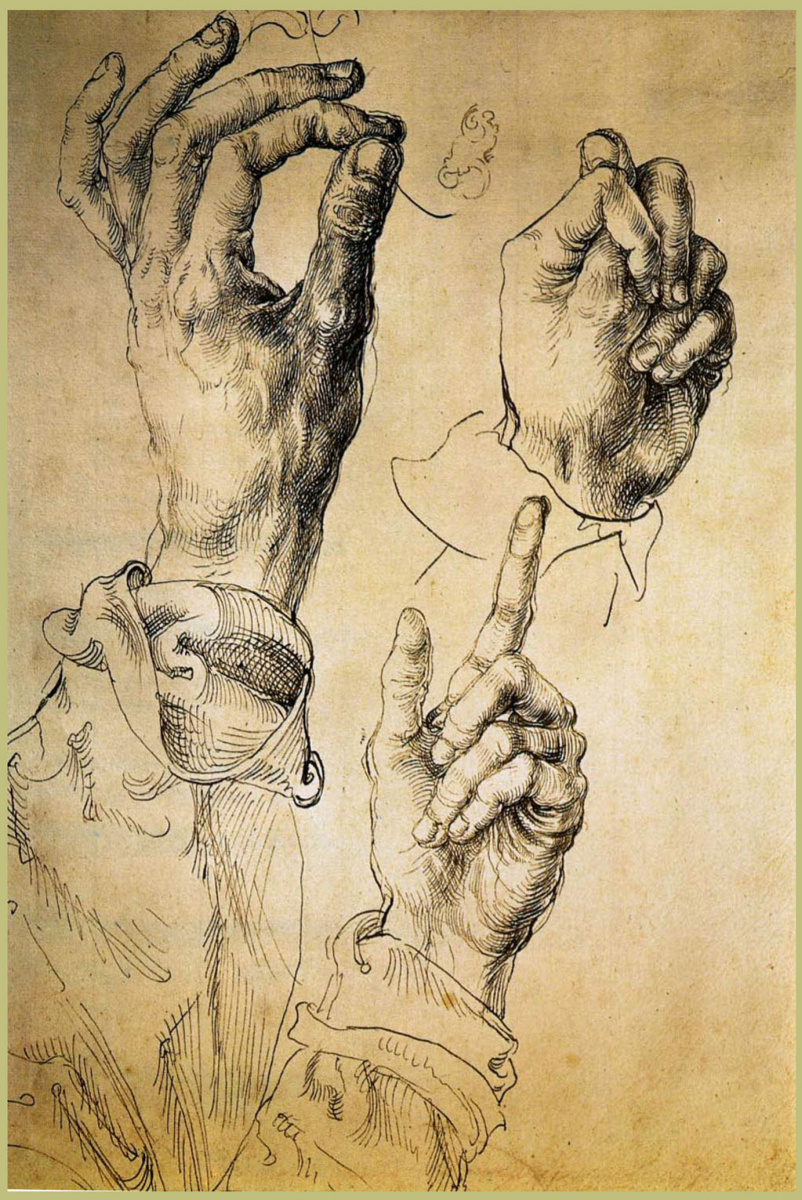

By the way, despite the fact that the Praying Hands is one of the most replicated drawings by Dürer, he had a great many sketches of hands. And not all of them are folded in prayer. At least one is giving a finger.

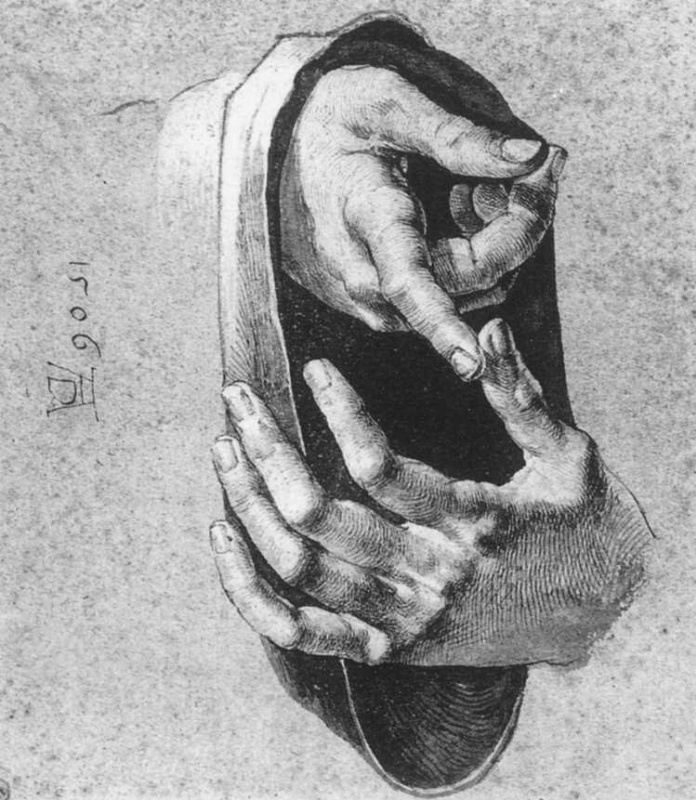

Study of three hands

1494, 27×18 cm

We invite the author of the heartbreaking story of the "praying hands" to come up with something sublime about this drawing. For example, "once the devil appeared to Dürer and offered to sell his soul for the opportunity to surpass Leonardo da Vinci, but Dürer was very pious and showed this figure to the devil, thereby shaming him, and then sketched this figure to always remember the strength of his faith. Although if the devil offered Dürer Jacopo de' Barbari’s notebook (with the calculation of perfect human proportions), Albrecht could have surrendered."

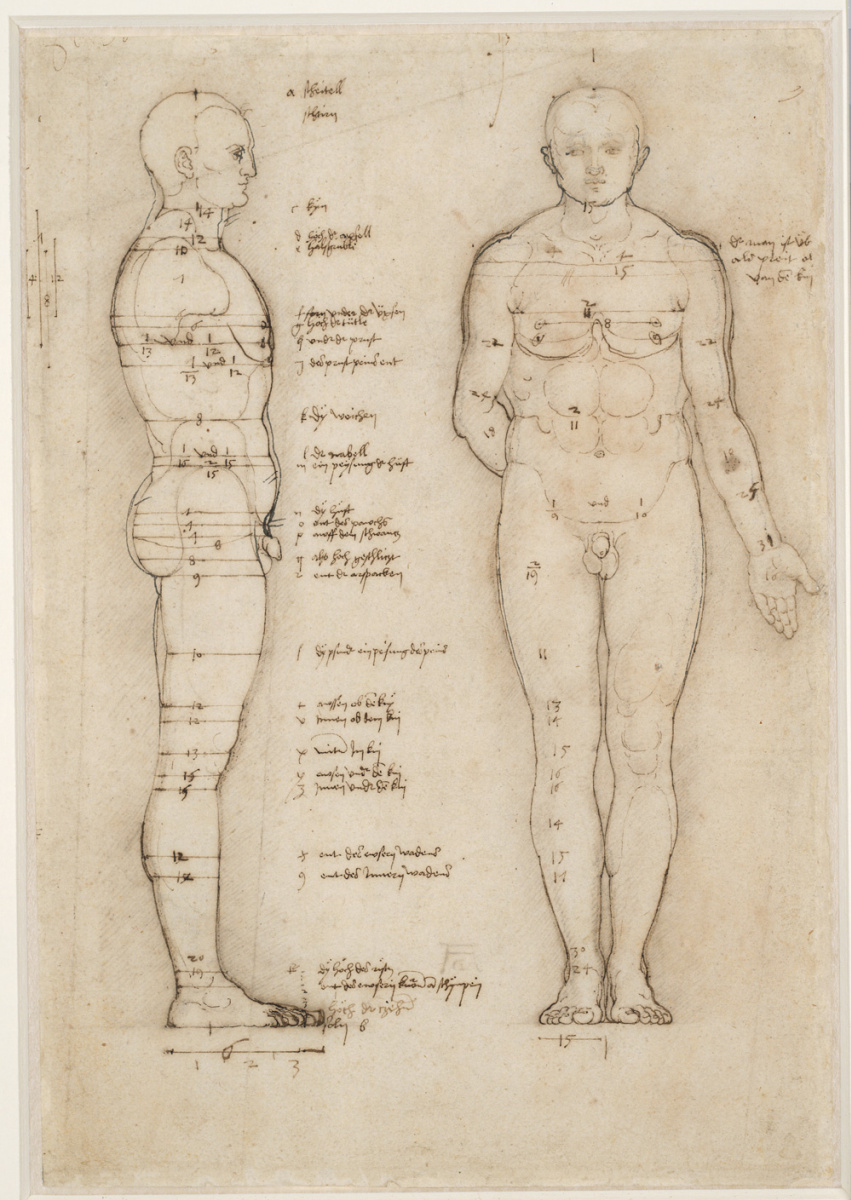

Male Nude. The study of proportions

1513, 26×18 cm

If someone wants to know, how the lives of the other "boys of the Dürer family" turned out, Hans and Endres outlived their older brother. Hans became a painter, Endres a goldsmith. Both were successful, but they did not leave much trace in art. Hans assisted Albrecht in the creation of the Geller’s Altar for which the Praying Hands may have been drawn. He was quick-tempered, there are documents about his participation in a fight, during which he was slightly wounded. He died at the age of 48 without any children (at least legal). Endres lived to be seventy years old. He inherited part of the property of Albrecht, and then, in 1540, most of the property of his late sister-in-law Agnes, after which he became quite rich. He was married to a widow with two daughters, but he did not leave his children, so one doesn’t need to write beautiful legends about his sons.