Frustrated, Frida Kahlo was finding that none of the letters she was writing felt quite right, and she tore them up, one by one. The young Mexican artist was penning a note to Georgia O’Keeffe — an artistic star nearly twice her age, whom she’d befriended while living briefly in New York about a year before. "I can’t write in English all I would like to tell, especially to you," reads the two-page letter Kahlo ultimately deemed worthy of sending. "I thought of you a lot and never forget your wonderful hands and the colour of your eyes. I will see you soon."

Sent on 1 March 1933, that letter is currently housed at the Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library at Yale University, and it is the sole document filed in the Alfred Stieglitz/Georgia O’Keeffe archive’s Kahlo folder. But Frida in America book reveals more details about the friendship between a 24-year-old Kahlo, then barely known as a painter, and a venerated and successful 44-year-old O’Keeffe. The study

issued in 2020 is dedicated to Mexican painter’s first trip to the United States — from 1930 to 1933, accompanying her husband Diego Rivera on multiple mural commissions.

The heartfelt conversations between the expansive self-portraitist and the eccentric artist who turned flowers into abstractions are a fantastic and very funny image. Understanding Kahlo’s friendship with O’Keeffe also helps flesh out the impact these formative American years had on the budding artist, as she bounced between San Francisco, New York, and Detroit. "It's important to understand more about this relationship between Frida and Georgia because it provides a fuller context, at least for Frida’s creative development," says Celia Stahr, author of Frida in America. "What did Frida see while she was in the United States, what did she experience?"

The two painters met in December 1931, at the opening of Rivera’s big solo exhibition at New York’s Museum of Modern Art. According to Lucienne Bloch, one of Rivera’s assistants, the famed muralist later bragged that his wife had been flirting with O’Keeffe (O'Keeffe already owned a Rivera painting, Seated Woman, making it likely that she and Stieglitz were on the list of people Kahlo felt she should chat up).

The two painters met in December 1931, at the opening of Rivera’s big solo exhibition at New York’s Museum of Modern Art. According to Lucienne Bloch, one of Rivera’s assistants, the famed muralist later bragged that his wife had been flirting with O’Keeffe (O'Keeffe already owned a Rivera painting, Seated Woman, making it likely that she and Stieglitz were on the list of people Kahlo felt she should chat up).

Frida and Diego Rivera

1931, 100×79 cm

Bloch kept a diary, which has not yet been published in its entirety. Celia Stahr consulted this document as she wrote her book, and in it she found evidence of what Kahlo filled her days with in the early 1930s. "I was able to get a much clearer sense of Frida’s social world," notes Stahr. "Little by little, I was able to piece out that yes, Frida’s hanging out with Georgia."

Sometimes they went on double dates with their husbands, and sometimes the two of them, plus Bloch, ventured out. "I love this one scene [from the journal] where Frida, Georgia, and Lucienne go to a Mexican restaurant together. They drink tequila, and then they end up getting tipsy and singing in the toilet," recalls Stahr. "I just think that’s an amazing image."

Sometimes they went on double dates with their husbands, and sometimes the two of them, plus Bloch, ventured out. "I love this one scene [from the journal] where Frida, Georgia, and Lucienne go to a Mexican restaurant together. They drink tequila, and then they end up getting tipsy and singing in the toilet," recalls Stahr. "I just think that’s an amazing image."

But their friendship wasn’t all flirtations and tequila. The two women were quite similar in many ways—both played with fashion, dressing themselves in striking ways outside the mainstream feminine vogue; both pursued careers of their own while married to older, unfaithful, and powerful male artists. "Both were fearless, flamboyant, and very powerful personalities," explains Linda Grasso, author of Equal under the Sky: Georgia O’Keeffe and Twentieth-Century Feminism (2017). "They automatically would have been attracted to each other."

In addition, Kahlo was looking closely at O’Keeffe’s paintings. In the spring of 1932, Kahlo and Rivera left New York for Detroit, where Kahlo painted Self-Portrait on the Border Line Between Mexico and the United States (1932)—a canvas depicting the artist in a pink gown, dividing a bleak landscape of American industry on the right and ancient Mexican ruins on the left. On the Mexican side, a few jack-in-the-pulpit flowers sprout between other plants — a flower that O’Keeffe devoted an entire series to just two years earlier and which isn’t indigenous to Mexico.

"You see not just one but three. You see the growth of it, the process—one's fully closed, one’s open," Stahr observes. "That's what Georgia showed in her series, this whole process of growth, and from different perspectives."

In addition, Kahlo was looking closely at O’Keeffe’s paintings. In the spring of 1932, Kahlo and Rivera left New York for Detroit, where Kahlo painted Self-Portrait on the Border Line Between Mexico and the United States (1932)—a canvas depicting the artist in a pink gown, dividing a bleak landscape of American industry on the right and ancient Mexican ruins on the left. On the Mexican side, a few jack-in-the-pulpit flowers sprout between other plants — a flower that O’Keeffe devoted an entire series to just two years earlier and which isn’t indigenous to Mexico.

"You see not just one but three. You see the growth of it, the process—one's fully closed, one’s open," Stahr observes. "That's what Georgia showed in her series, this whole process of growth, and from different perspectives."

Even in Detroit, when it was unclear whether she’d ever see O’Keeffe again, the older artist’s influence lingered. Their next known contact was when Kahlo phoned O’Keeffe sometime in late 1932, after learning that she’d suffered a nervous breakdown. When Kahlo mailed her letter to O’Keeffe in 1933, she was hospitalized.

"If you are still in the hospital when I come back I will bring you flowers, but it is so difficult to find the ones I would like for you," Kahlo wrote at the end of her note. "I like you very much Georgia." Kahlo returned to New York two weeks later, and visited her friend right before O’Keeffe left for Bermuda to continue her recovery.

"If you are still in the hospital when I come back I will bring you flowers, but it is so difficult to find the ones I would like for you," Kahlo wrote at the end of her note. "I like you very much Georgia." Kahlo returned to New York two weeks later, and visited her friend right before O’Keeffe left for Bermuda to continue her recovery.

Kahlo rehashed the reunion in a letter to Clifford Wight, one of Rivera’s assistants. "She didn’t make love to me that time," she lamented. "I think on account of her weakness. Too bad." Kahlo’s wording implies that O’Keeffe had made love to her before, but it’s unclear what she meant exactly. While some scholars argue that O’Keeffe had romantic relationships with women, the official line from the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum and major O’Keeffe scholars is that there’s no evidence. "The term ‘make love' had a variety of meanings," offers Grasso. "It might have just meant flirting."

The story of Kahlo and O’Keeffe’s friendship is fairly one-sided, with most of the records coming from Kahlo (to whom the relationship likely meant more). No letters have been identified, to date, from O’Keeffe, and it doesn’t look like she kept any mementos.

The story of Kahlo and O’Keeffe’s friendship is fairly one-sided, with most of the records coming from Kahlo (to whom the relationship likely meant more). No letters have been identified, to date, from O’Keeffe, and it doesn’t look like she kept any mementos.

One small trace, which Grasso identified recently in an O’Keeffe address book from the early 1930s, is a Chicago address for Frida Rivera (the artist’s married name). When Kahlo was in New York in 1933, her next scheduled destination was Chicago (where Rivera was commissioned to paint a mural for the World’s Fair, which fell through after the controversy surrounding his Rockefeller Centre mural).

O’Keeffe probably never used that Chicago address, but when the Mexican painter came to New York in November 1938 for her first solo exhibition, at the Julien Levy Gallery, O’Keeffe was there on opening night. Stahr thinks this was deliberate, since by this point she was spending July through December in New Mexico, and could have easily missed Kahlo’s exposition.

O’Keeffe probably never used that Chicago address, but when the Mexican painter came to New York in November 1938 for her first solo exhibition, at the Julien Levy Gallery, O’Keeffe was there on opening night. Stahr thinks this was deliberate, since by this point she was spending July through December in New Mexico, and could have easily missed Kahlo’s exposition.

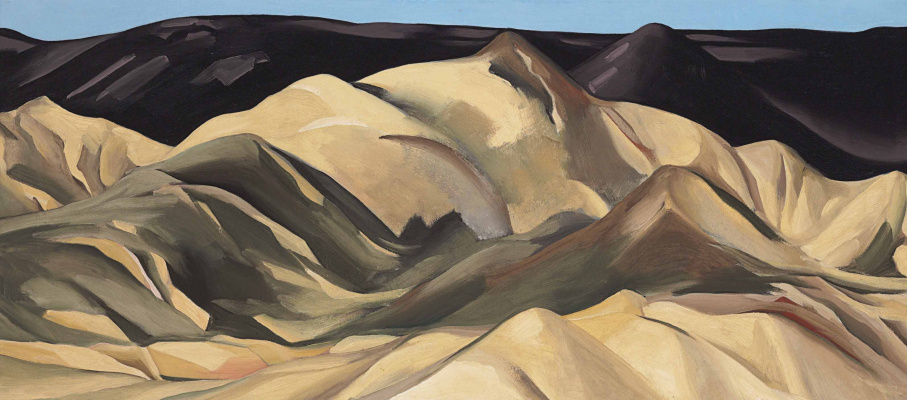

Near Abiquiu, New Mexico

1931, 40.6×91.4 cm

"It's possible they saw each other other times," Stahr adds. "Frida did visit New York on different occasions." And when O’Keeffe travelled to Mexico in 1951, she visited Kahlo twice at her home, the Casa Azul (Azure House).

That last time, it was Kahlo who was confined to bed, recovering from recent operations. She must have been thrilled to see her old pal, who showed her what being a successful woman artist could look like. "O'Keeffe was the woman artist… the representative, the token, the exemplar," Grasso says. "You can think about how much O’Keeffe—as a person, as a friend, as a woman, and as an artist—might be absolutely fascinating and important to her."

Maybe O’Keeffe brought Kahlo flowers, and maybe Kahlo offered her friend some local tequila. The two were different people than when they first met, two decades earlier, and they hadn’t been permanent fixtures in each other’s lives. Their bond, however loose, was still there.

That last time, it was Kahlo who was confined to bed, recovering from recent operations. She must have been thrilled to see her old pal, who showed her what being a successful woman artist could look like. "O'Keeffe was the woman artist… the representative, the token, the exemplar," Grasso says. "You can think about how much O’Keeffe—as a person, as a friend, as a woman, and as an artist—might be absolutely fascinating and important to her."

Maybe O’Keeffe brought Kahlo flowers, and maybe Kahlo offered her friend some local tequila. The two were different people than when they first met, two decades earlier, and they hadn’t been permanent fixtures in each other’s lives. Their bond, however loose, was still there.

Based on Karen Chernick, Frida Kahlo and Georgia O’Keeffe’s Formative Friendship on Artsy