Their life together was a real everyday nightmare, and at the same time an ideal creative union. He considered her a worthless housewife, and she considered him an incorrigible egoist. They tormented each other, cursed and fought, but they could not live without each other. Edward Hopper and his biographers treated Josephine with condescension at times, but he would not have become one of America’s greatest artists without her.

At the beginning of her relationship with Edward Hopper in 1923, Josephine Nivison was an actual artist. Her artworks were exposed alongside paintings by Picasso, Modigliani and Man Ray in prestigious New York galleries. Shortly before the fateful meeting, the Brooklyn Museum invited Jo to participate in the next exhibition with her watercolours — along with the works by Georgia O’Keeffe and John Singer Sargent. Hopper, meanwhile, earned his living by working in advertising magazines and slowly plunged into depression due to unrecognition and inability to sell at least one painting in a decade. Josephine was the first to discern the future genius of American painting in Edward. Wanting to help him, Nivison persuaded the curators of the Brooklyn Museum exhibition to include Hopper’s work on the display.

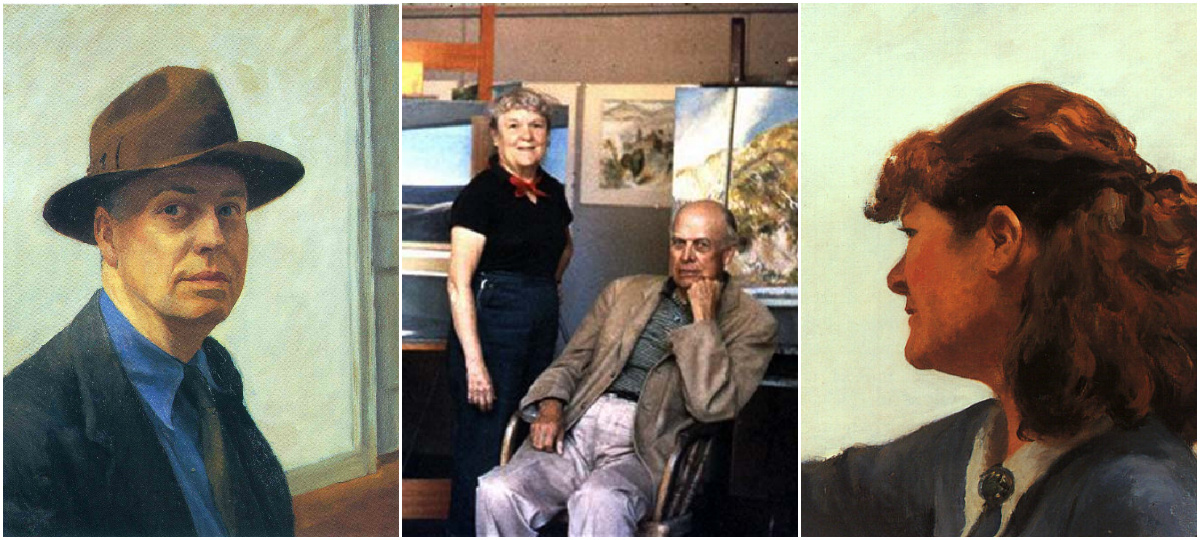

Edward and Jo at the beginning of their life together

This exhibition surely changed the course of history. It was from this moment that the growth of Edward Hopper’s career began. Unfortunately, this very moment marked the beginning of the end of Josephine Nivison’s career.

Croix de Guerre

For nearly two-thirds of his life, Edward Hopper lived and worked in New York, in a studio on the top floor of a building overlooking Washington Square. There was no refrigerator or toilet, and to heat the room, he had to carry coal up the stairs constantly. But this apartment was perfect for work: it was very bright thanks to the skylight. Hopper placed a mirror next to the easel, and, looking into it, saw the next room — Jo’s almost empty studio. She watched him while he watched her.

Jo in Wyoming

1946, 35.4×50.8 cm

Edward and Jo went on creative travels to Massachusetts, Maine or Mexico from time to time, but they still spent most of the time in this small apartment, in four walls, almost without seeing other people, and eating canned food. Art historian Gail Levin, who wrote 10 books about Hopper, said: "They spent nearly 24 hours a day, seven days a week together for three years. It’s hard for any couple." In his numerous diaries, besides detailed descriptions of the Edward’s creative process, Josephine talks about violent quarrels, sometimes fights. Jo scrabbled at her husband and "bit him to the bone", Hopper slapped her in the face and beat her, leaving bruises. Domestic violence has even become the subject of dubious jokes for spouses. On their 25th wedding anniversary, Jo told her husband that they both deserved their own Croix-de-Guerre, a military service award. Edward supported the joke and made a cross-shaped coat of arms of a rolling pin and a ladle.

From artist to muse

Before meeting Edward Hopper, Josephine Nivison’s life was difficult, but always intense, and certainly not boring. She was born in New York on 18 March 1883 to the family of a pianist and a music teacher. The family’s financial situation was always difficult and they had to move frequently. In 1900, Josephine entered the free teacher training college for women. While still a student, she began to draw, and after graduation she decided to get an art education. Teaching at a public school to make her living, Jo studied painting with Robert Henry at the New York School of Art. And later she kept in touch with her mentor and colleagues, and even travelled with them to Europe. In parallel with this, Nivison played in productions of a small local theatre, and during the summer holidays she lived in various art colonies in New England.

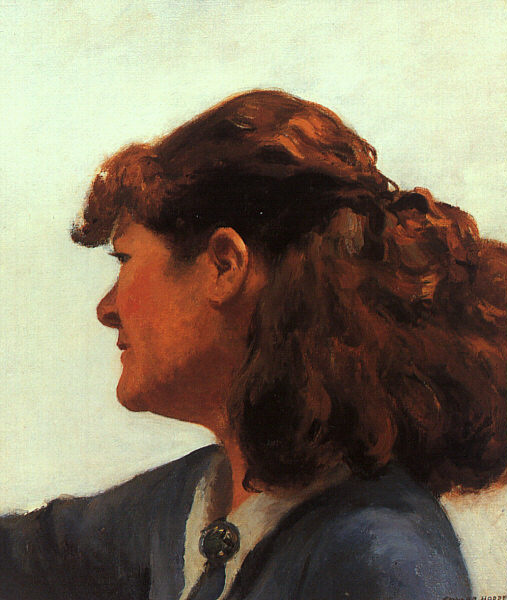

Robert Henry "Student Artist (Miss Josephine Nivison)"

At the end of the First World War, Josephine wanted to change the situation and her field of activity. She unsuccessfully tried to get a job in the Red Cross. In the end, she managed to find a job in a hospital abroad, but just a couple of months later, Jo was forced to return home with severe bronchitis. When she was discharged from the hospital almost six months later, it turned out that Josephine had lost her teaching position, and thus her earnings and housing. At some point, she found herself in the Church of the Ascension of the Lord, sobbing on a bench with despair, where an old sexton discovered her and helped her find a temporary refuge. Only a year later, the Board of Education allowed Josephine to teach again, and she continued to teach children, while pursuing an artistic career.

New York Cinema

1939, 81.9×101.9 cm

This is not to say that after marriage, Josephine’s life became boring and monotonous. It’s just that there was almost nothing of Jo in this life. Her whole life only concentrated on her husband, his interests and his career. She became the main muse, the ideological inspirer, the notorious support. Her diaries were filled with stories about living together and detailed descriptions of her husband’s work. She meticulously recorded every sale and conducted all his correspondence. Jo wrote: "If there can be room for just one of us, then surely it must be him. And I can be glad and grateful for that." Perhaps for many women, the role of the main (and in fact the only) muse could be a source of pride. But Josephine Nivison, once becoming a muse, forever ceased to be the artist whose paintings hung next to Picasso and O’Keeffe.

The woman of many faces

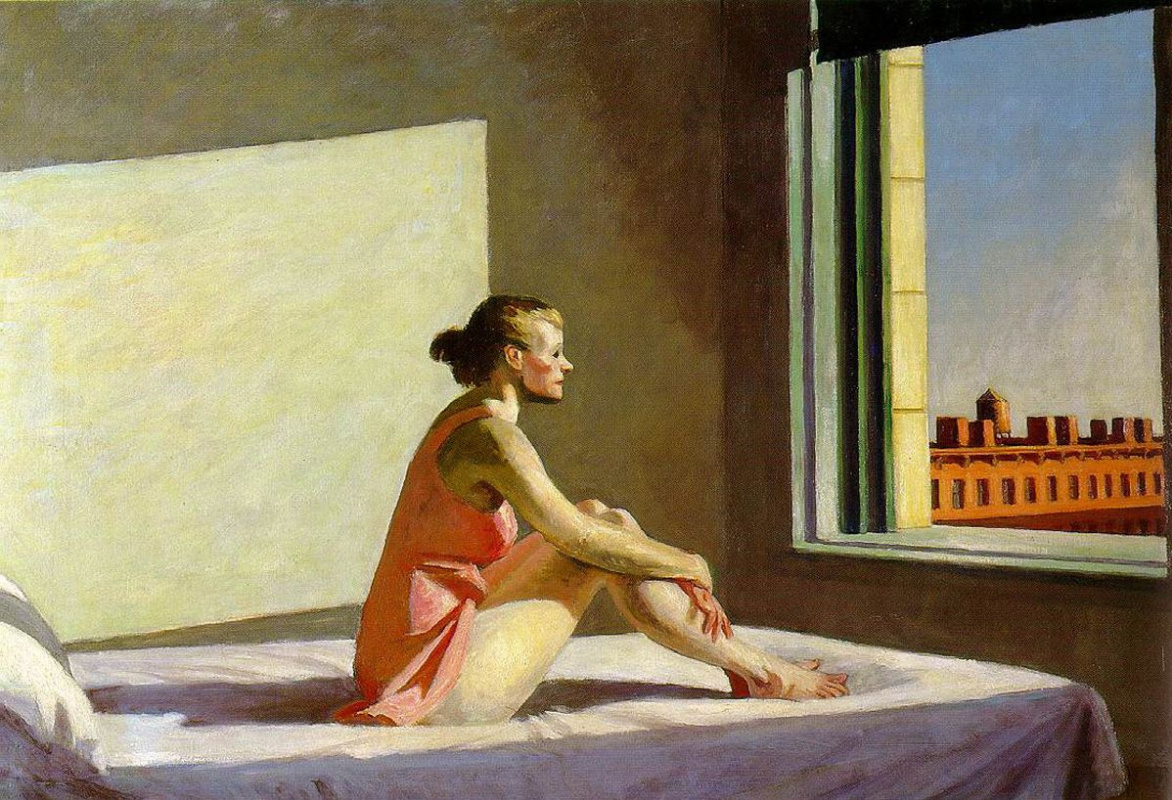

A woman sits on a bed in a stream of sunlight from a window. Another woman is leaning against the wall in a New York movie theatre. The third one sits at the counter of a night café. Dozens of women in offices and apartments, in different interiors and outfits. Each of them is Jo Nivison Hopper. Acting experience helped her to reincarnate, adjusting to the ideas of her husband. In one of her diaries, Josephine wrote how she burned her leg on the stove, posing nude for another Hopper painting, and was very proud of it.

The morning sun

1952, 101.9×71.5 cm

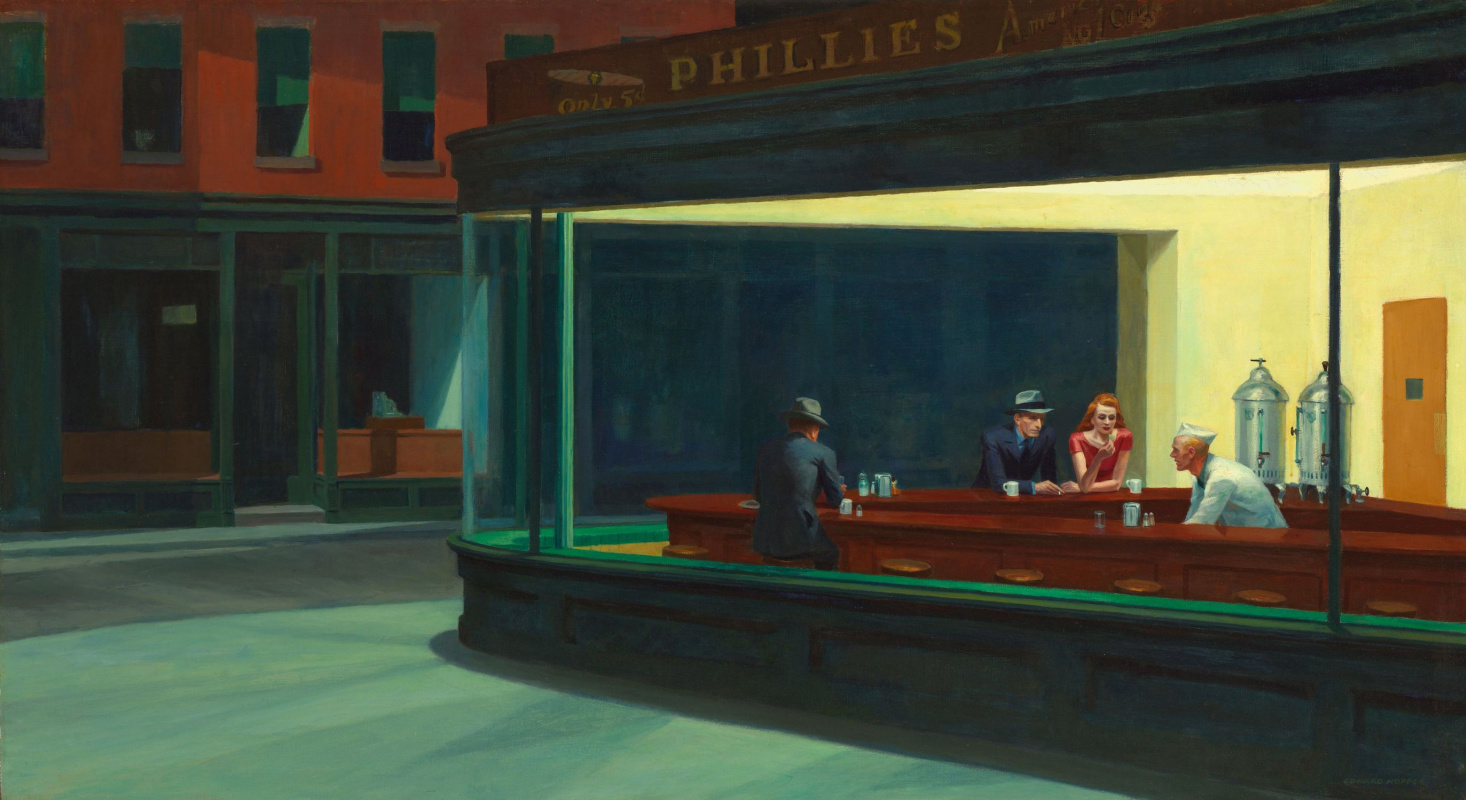

Jo has come up with titles for many of her husband’s paintings, including the famous Nighthawks. She wrote the names and stories for the subjects in these artworks, and then she and Edward discussed what these fictional characters could do, their daily habits and preferences. This union was important and valuable to both of them. At the very beginning of their relationship, it was Jo who persuaded Hopper to start painting watercolours. For more than 40 years of marriage, she helped him get out of his creative stupor multiple times. Josephine wrote that Edward had a very strong competitive spirit, and to get him to paint, she just had to start her own painting.

Nighthawks

1942, 84.1×152.4 cm

When she married Hopper, Jo did not stop painting. But, according to art critics, the most powerful of her works are still those that were painted before marriage. In her diaries, she complained that her husband did not support her work. Although some experts suggest that Josephine, who once showed great promise, simply did not have enough talent, and her work quickly ceased to correspond to the spirit of the time. Of course, if Edward had more support for his wife, she might have been able to develop and become a popular and salable artist. However, now the answer to this question can no longer be found.

Jo drawing

1936, 45.7×40.6 cm

Josephine with her painting

Ever since Gail Levin, who had exclusive access to Jo Hopper’s diaries, released quotes from them, there has been a debate in the art world about whether absolutely everything in these entries can be taken for granted. Barbara Novak, who was one of the few close friends of the Hopper family, said Jo "saw the world through the barbed wire of resentment. These tirades were part of her eccentricity. She was insane, but deliciously insane. She was a brilliant, extraordinary woman, but completely without a sense of humour."

A lighthouse and a bird

Several years ago, the Edward Hopper Art Centre in his native Nyack opened an exhibition of his cartoons — small pencil drawings created between 1933 and 1952. All of them are devoted to the artist’s family life and all represent Josephine in a rather unattractive light. Hopper drew these hurtful pictures when Jo left the room and left them on the table for her to see when she returned. In them, Edward portrayed himself as a victim of her aggressive attacks, ridiculed her inept household attempts and her artistic ability. Of course, these cartoons are biased and one-sided, it was a kind of revenge of the laconic Hopper on his wife, who, in his opinion, was completely unable to cope with this role.From Jo’s point of view, things certainly looked different. In her diaries, she tells how all her emotional attempts to reach out to her unshakable husband failed over and over again. "His ego is so impenetrable! The lighthouses he paints are self-portraits. I have always been so sorry to see the birds that crashed into the Cape Elizabeth lighthouse at night. And I know exactly how they felt."

One of the reasons for the constant fights in the Hopper house was their sex life. When they got married, both were in their forties, but the withdrawn and shy Edward didn’t have much experience, and Jo didn’t have it at all. Due to their puritanical upbringing, they could not talk about it either with each other, much less with anyone else. Josephine could only complain in her diaries that her husband only cared about himself in bed, and she felt abnormal without any pleasure.

One of the reasons for the constant fights in the Hopper house was their sex life. When they got married, both were in their forties, but the withdrawn and shy Edward didn’t have much experience, and Jo didn’t have it at all. Due to their puritanical upbringing, they could not talk about it either with each other, much less with anyone else. Josephine could only complain in her diaries that her husband only cared about himself in bed, and she felt abnormal without any pleasure.

Eleven in the morning

1926, 71.4×91.8 cm

The Hoppers never had children of their own (perhaps they got married too late for that), and Jo often referred to them as the common children of Edward’s painting. She wrote that the New York Cinema painting was greeted by the gallery owner "as a newborn heir". At the same time, Josephine spoke of her own works as "poor little stillborn babies". Jo once said to one of the museum curators: "I don’t like them too much. And how sad that even I reject them."

Josephine Nivison Hopper "Obituary (Flowers of Time Passed)" (1948)

Josephine bequeathed all of her husband’s and her own works to the Whitney Museum. But, unlike the paintings of the famous Edward Hopper, Jo Hopper’s works were of no interest to the museum curators and were sent to the archive. For several decades, these paintings were considered lost or destroyed, until in 2000 they were found in the basement of the museum by art critic Elizabeth Thompson Colleary. It wasn’t until the 21st century that Jo Hopper’s work finally began to be exhibited again.

Edward and Jo in the studio

They lived together for over 40 years, their marriage was a real disaster, each of them could leave at any moment. But they needed each other. Jo wrote: "Ed is the centre of my universe. What a blessing that we have each other. I will be allowed to leave only when he is gone." When Edward died in May 1967, Jo said that she felt as if her limb had been amputated. She survived him by only 10 months. Family friend Barbara Novak said, "We don’t know what she died of. But I think she died from his absence. And he would have died from her absence. It was the most real madness together".