Hendrick Avercamp, Ice Scene (c. 1625)

The Dutchman Hendrick Avercamp was one of the first Western artists to paint winter landscapes. His paintings often feature a special grey light as the sun struggles to break through the clouds and the horizon is lost in a haze. The Avercamp’s ice-covered pond is a social space, and he portrays winter as a social phenomenon that affects not only work, but also clothing, fashion, games, and even romantic relationships.The painting was painted in the first half of the 17th century, during the Little Ice Age. Winters were harsh back then, and the climate had a significant impact on agriculture, followed by culture and politics.

Matthew Capucci (in the photo) says: "I see the first breath of spring. Of course it’s still cold, the ice is thick enough to hold the horse. But it is slightly hazy with all shades of grey, and some details in the background are slightly distorted. This makes me think there is a little more moisture in the air than there was at that time in winter. So this is probably the end of February — the beginning of March, that first thaw, when the ice is still there, but the heat from the south raises the moisture level. Cold ice comes into contact with it, causing condensation, so a haze forms at the surface. The clouds are not too high — they are not thunderclouds, but the shallow layer that forms with the first warm breeze of spring. The Little Ice Age was especially difficult for Europe, but it seems to me that the artist wanted to show the opposite. People look so energetic, there is a hint of warmth. Maybe he’s trying to portray a ray of hope?"

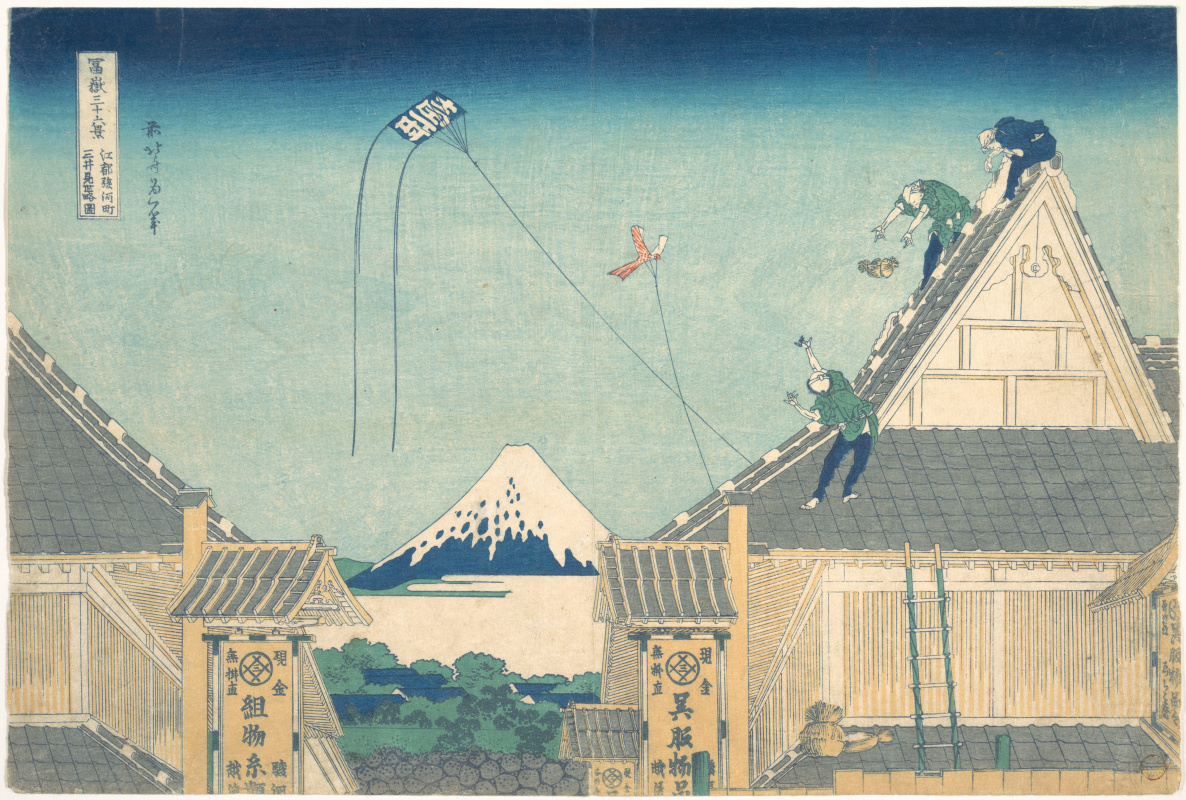

Katsushika Hokusai, Mitsui Shop at Surugachō in Edo (c. 1830)

This image of Mount Fuji was taken between 1830 and 1832. A characteristic peak can be seen in the distance behind a small store, which became the ancestor of one of the largest modern corporations in Japan. The engraving is part of the Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji series, one of the most popular ones by Katsushika Hokusai. In this cycle, the iconic mountain was the starting point and backdrop for depicting details of everyday life, social customs and the natural world.Hokusai created these prints around the time when the price of the rich, vibrant blue pigment was falling and it was becoming more accessible to Japanese artists. In this work, colour is important for conveying the feeling of good weather — along with the nice breeze that keeps the kites in the sky. Sometimes a new material or technique not only helps the artist portray what he sees, but literally helps the vision process. When you fall in love with a certain shade of blue, you suddenly notice clear weather.