log in

Enter site

Login to use Arthive functionality to the maximum

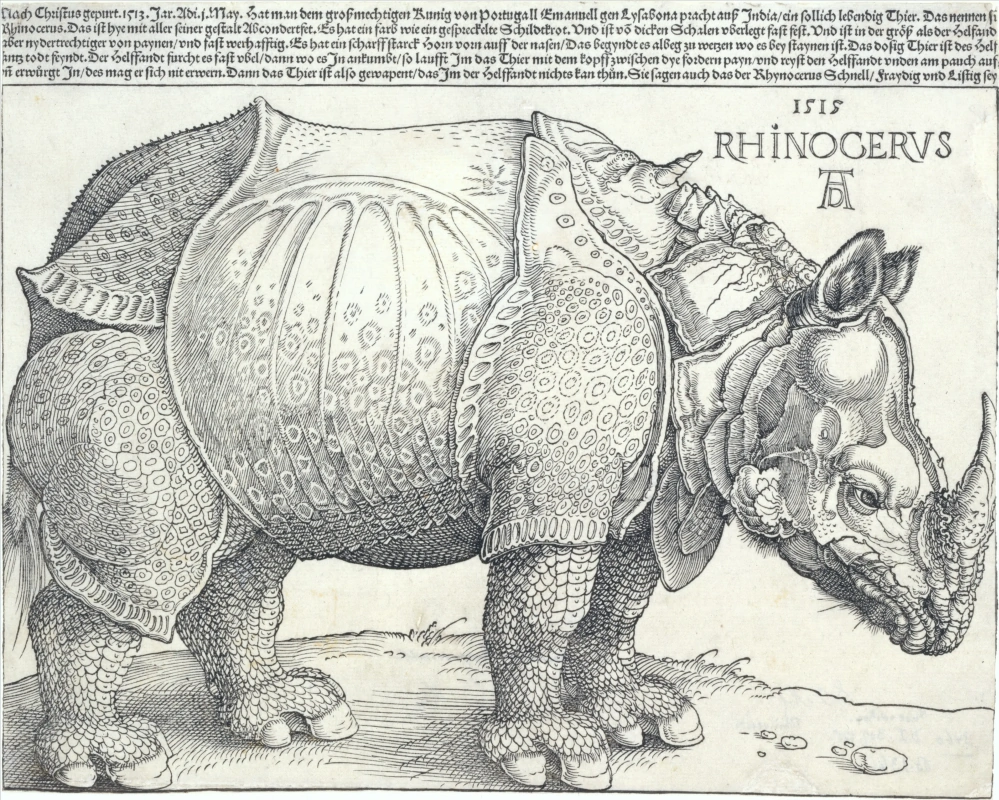

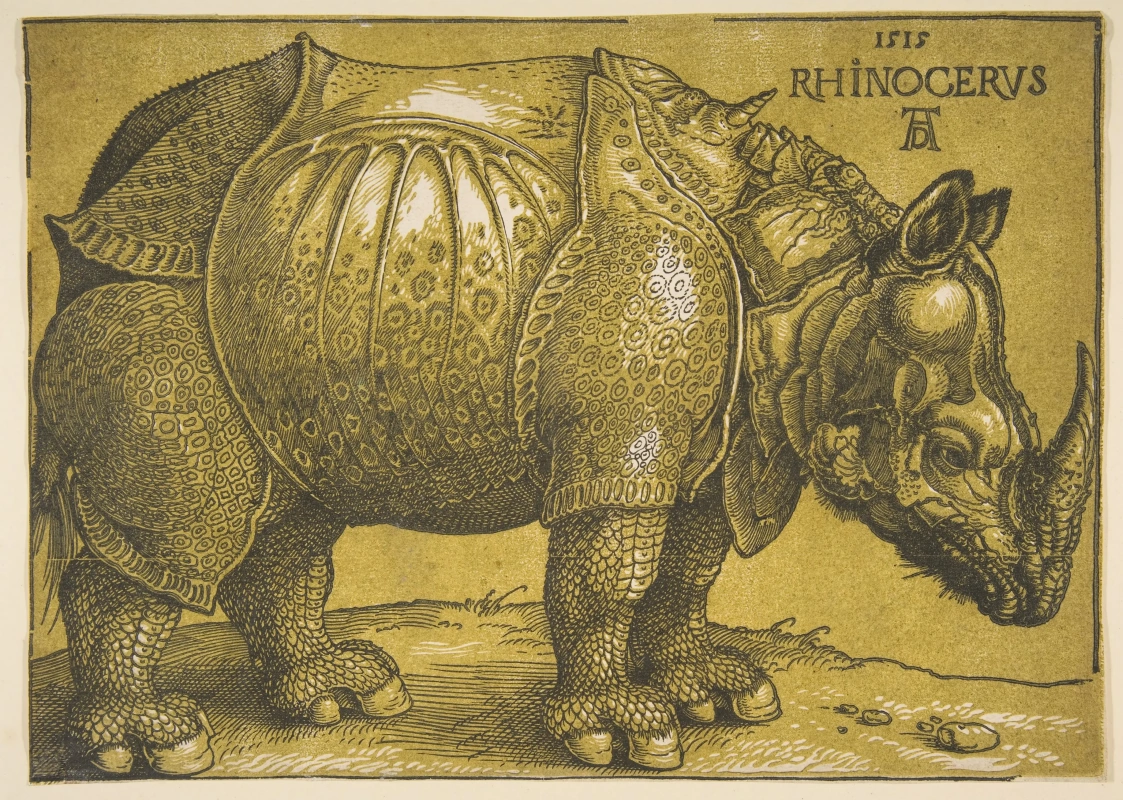

Rhino

Albrecht Dürer • Print, 1515, 23.8×29.9 cm

Description of the artwork «Rhino»

This image of a rhino is perhaps the most famous in the history of art. Dürer himself never saw an animal. He based his famous woodcut on a certain description and sketch of the beast, which the ruler of Gujarat, Sultan Muzafar II, presented to the governor of Portuguese India, Alfonso d'Albuquerque. He, in turn, sent a living present to Lisbon to King Manuel I in the spring of 1515. Most likely, the story and drawing were sent to Nuremberg by the German printer Valentin Ferdinand, who lived in Portugal. The text reads:

“In 1515, on May 1, an animal from India called a rhino was delivered to our king of Portugal in Lisbon. Since this is a curiosity, I decided to send you an image of it. It is similar in color to a toad, covered with thick scales and well protected, equal in size to an elephant, but lower. This beast is the elephant's mortal enemy. In front of his nose he has a strong sharp horn, and when he approaches the elephant, he first sharpens the horn against the stones, and runs to the elephant, sticking his head between his front legs, and rips open his belly, and he cannot defend himself. Therefore, the elephant is afraid of the rhinoceros, he is well armed, very cunning and vigilant. The animal is called a rhinoceros in Greek and Latin, and in India - gomda ".

In the creative interpretation of Dürer, it is a sturdily built mammal with thick skin, covered with armor. It emphasizes the heavy structure of the animal's body and makes it even rougher with woodcuts. By transferring the original drawing to the wood panel, the artist exposes the texture of the rhinoceros skin through the bumps that leave streaks in each print.

Durer wanted to make the outlandish beast even more menacing and armed him with a sharp horn on his back (it is located on the engraving next to the letter R). But even if the artist was mistaken in his interpretations, he still very accurately conveyed the character of a giant. This rhino is a real miracle of the animal world.

In Europe, this mammal was a curiosity, and it was also depicted by other artists, including Hans Burgkmair and Francesco Granacci (possibly also Giovanni Penny). But their work went unnoticed, while Dürer's woodcut took on the status of a visual icon. Indeed, in comparison with other images, his technical skills are obvious, while the sketches of his colleagues look almost comical.

Numerous artists have imitated Dürer's rhinoceros in sculptures, tapestries and ceramics. Even naturalists such as Konrad Gesner have used his presentation in their scientific compilations of natural history. Dürer deliberately made a large number of prints from the original woodcuts in order to maximize his image.

Dürer edited the text accompanying his image of the rhinoceros when he transferred the drawing to the panel. In woodcuts, he further emphasizes his own skills and ability to recreate an animal that he has never even seen. The artist makes strategic adjustments to the description to validate the authenticity of his print. For example, he compares a rhinoceros to a speckled turtle, and not to a toad: the shell of a turtle is hard, therefore, its texture is more suitable for a rhinoceros than toad skin. This logical conclusion convinces Dürer himself, and he makes the audience believe that the rhino is reproduced in full accordance with the original.

The artist's masterly drawing skill casts doubt on the value of direct observation. In addition to its aesthetic appeal, Dürer's Rhino proves that during the Renaissance, people sought to gain knowledge not only through physical encounter with nature, but also through visual materials that were perceived as realistic.

“In 1515, on May 1, an animal from India called a rhino was delivered to our king of Portugal in Lisbon. Since this is a curiosity, I decided to send you an image of it. It is similar in color to a toad, covered with thick scales and well protected, equal in size to an elephant, but lower. This beast is the elephant's mortal enemy. In front of his nose he has a strong sharp horn, and when he approaches the elephant, he first sharpens the horn against the stones, and runs to the elephant, sticking his head between his front legs, and rips open his belly, and he cannot defend himself. Therefore, the elephant is afraid of the rhinoceros, he is well armed, very cunning and vigilant. The animal is called a rhinoceros in Greek and Latin, and in India - gomda ".

In the creative interpretation of Dürer, it is a sturdily built mammal with thick skin, covered with armor. It emphasizes the heavy structure of the animal's body and makes it even rougher with woodcuts. By transferring the original drawing to the wood panel, the artist exposes the texture of the rhinoceros skin through the bumps that leave streaks in each print.

Durer wanted to make the outlandish beast even more menacing and armed him with a sharp horn on his back (it is located on the engraving next to the letter R). But even if the artist was mistaken in his interpretations, he still very accurately conveyed the character of a giant. This rhino is a real miracle of the animal world.

In Europe, this mammal was a curiosity, and it was also depicted by other artists, including Hans Burgkmair and Francesco Granacci (possibly also Giovanni Penny). But their work went unnoticed, while Dürer's woodcut took on the status of a visual icon. Indeed, in comparison with other images, his technical skills are obvious, while the sketches of his colleagues look almost comical.

Numerous artists have imitated Dürer's rhinoceros in sculptures, tapestries and ceramics. Even naturalists such as Konrad Gesner have used his presentation in their scientific compilations of natural history. Dürer deliberately made a large number of prints from the original woodcuts in order to maximize his image.

Dürer edited the text accompanying his image of the rhinoceros when he transferred the drawing to the panel. In woodcuts, he further emphasizes his own skills and ability to recreate an animal that he has never even seen. The artist makes strategic adjustments to the description to validate the authenticity of his print. For example, he compares a rhinoceros to a speckled turtle, and not to a toad: the shell of a turtle is hard, therefore, its texture is more suitable for a rhinoceros than toad skin. This logical conclusion convinces Dürer himself, and he makes the audience believe that the rhino is reproduced in full accordance with the original.

The artist's masterly drawing skill casts doubt on the value of direct observation. In addition to its aesthetic appeal, Dürer's Rhino proves that during the Renaissance, people sought to gain knowledge not only through physical encounter with nature, but also through visual materials that were perceived as realistic.