Throughout nearly all human history, dogs have been not only guardians, helpers, and companions, but also muses. They have been immortalised in paintings and sculptures, prints and photographs (and even in monumental balloon-like constructions). Now that centuries have passed, dogs are still our companions and living symbols of protection, loyalty, and unconditional love. So, it is no secret why they have been a very important and noticeable part of our visual history for so long a time.

Canine symbolism in different cultures

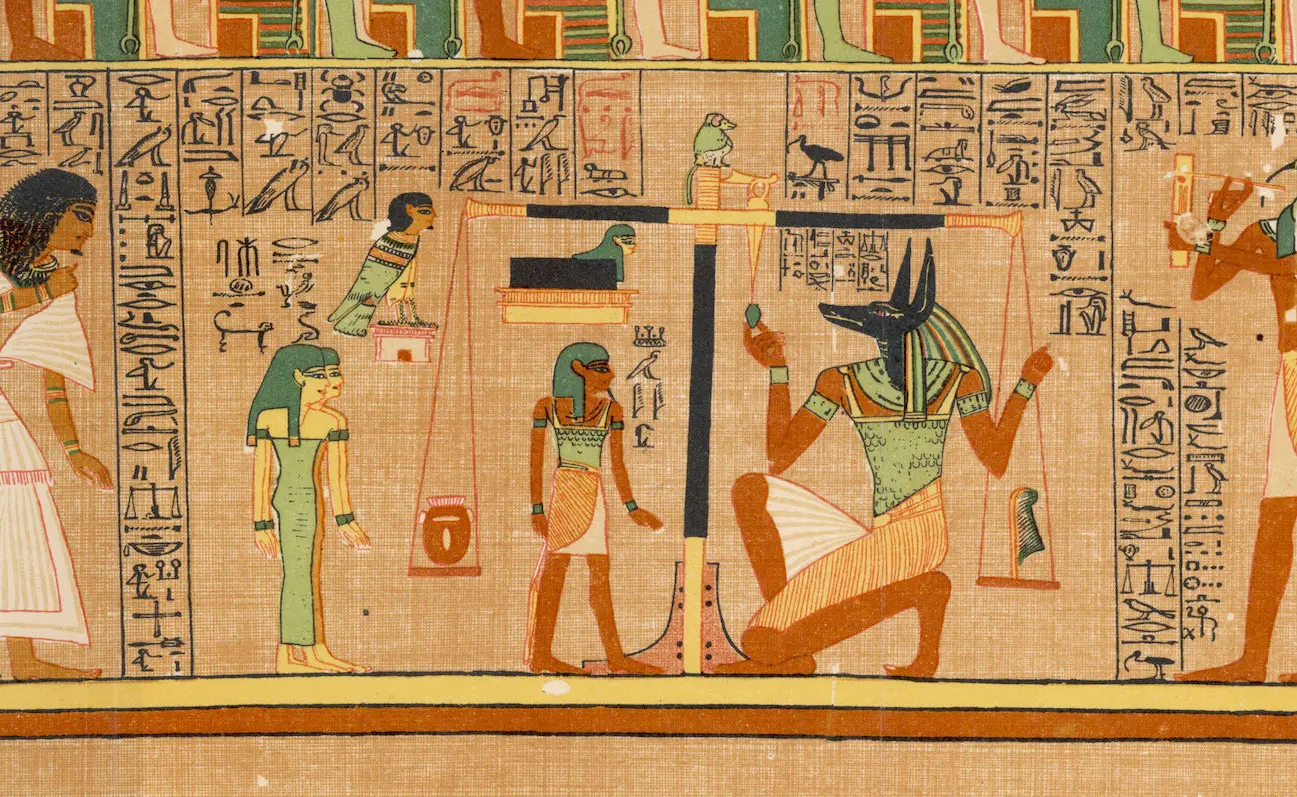

For a long time, dogs were viewed as guides, a liaison between our physical world and beyond. The Ancient Egyptians, Greeks, Romans, Celts, and others saw the dog’s role in being the sacred keeper of other worlds that are beyond our earthly experience. That is the very reason why the dog is sometimes called the symbol of death: it can be a sentinel of immaterial spheres and a guide in out-of-body travels. As an example, you may recall Anubis, the canine-headed Egyptian god, who ushered souls into the afterlife.

The dog was the sacred animal that accompanied the Greek goddess Hecate, whose domain was shadows, sorcery, and nightmares. However, Hecate and her dog companions were also guards and protectors for those unable to take care of themselves: children and infants, the weak and the meek, insane and slandered people.

In Celtic beliefs, dogs symbolised heroism and embodied the qualities so important for a warrior: bravery, endurance, and courage. The Celts did not only use dogs when hunting, but also trained them to assist in battles. Besides, a Celtic dog was a symbol of the medical arts. These animals were often associated with Nodens, a Celtic deity of beneficial waters, hunting, and healing.

For the Chinese, from time immemorial, dogs have not only symbolised loyalty and obedience, like for many other nations, but also good luck and prosperity. It is believed that a dog, by wagging its tail, heralds great wealth. And the powerful Feng Shui talisman — a pair of Foo dogs — protects the building from harmful people and negative energies, helps succeed in business and improve the welfare. Foo dogs are also known as Imperial guardian lions, and that is the reason why Pekingese dogs were intentionally crossbred so that they resembled tiny lions as much as possible.

In Celtic beliefs, dogs symbolised heroism and embodied the qualities so important for a warrior: bravery, endurance, and courage. The Celts did not only use dogs when hunting, but also trained them to assist in battles. Besides, a Celtic dog was a symbol of the medical arts. These animals were often associated with Nodens, a Celtic deity of beneficial waters, hunting, and healing.

For the Chinese, from time immemorial, dogs have not only symbolised loyalty and obedience, like for many other nations, but also good luck and prosperity. It is believed that a dog, by wagging its tail, heralds great wealth. And the powerful Feng Shui talisman — a pair of Foo dogs — protects the building from harmful people and negative energies, helps succeed in business and improve the welfare. Foo dogs are also known as Imperial guardian lions, and that is the reason why Pekingese dogs were intentionally crossbred so that they resembled tiny lions as much as possible.

Foo dugs. 19th century

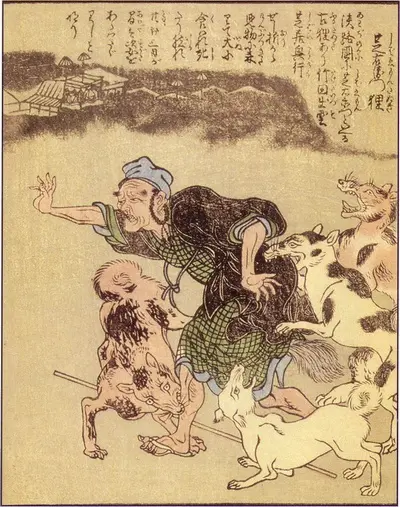

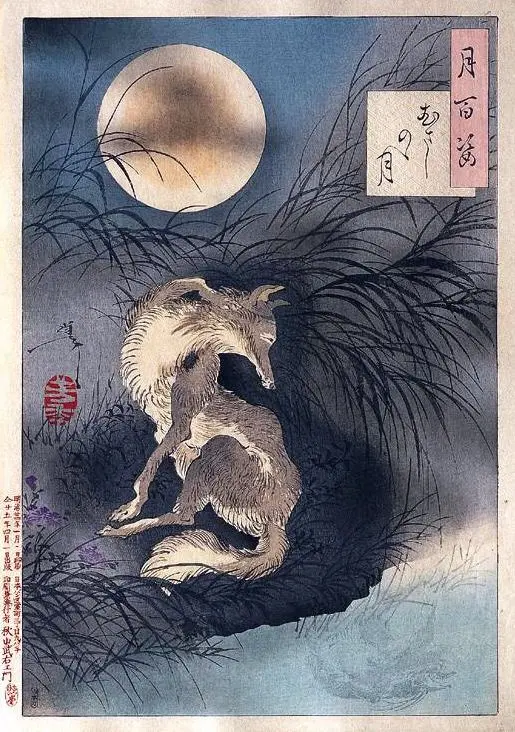

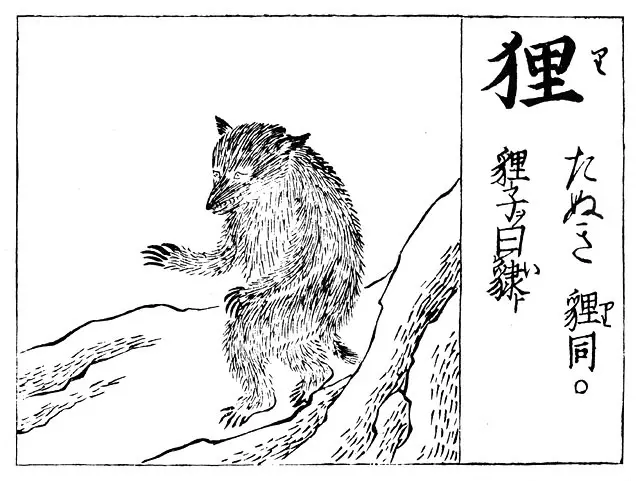

The Japanese raccoon dog, Tanuki, is a favourite subject both in traditional and in modern Japanese art. In folklore and legends, these animals are described as having paranormal abilities. Like the werefox Kitsune, Tanuki can shapeshift into other animals, people, and things. In the earliest folk tales, these creatures boded misfortunes, turned into humans, and could possess people. Now, centuries later, Tanuki has become a sort of trickster, mischievous, deceitful, but harmless. Tanuki’s ceramic statues can be seen all over Japan, especially in bars and restaurants.

In traditional Japanese art, Tanuki were often depicted beneath the moon, because a full-moon night was believed to be the time for Tanuki to transform into other creatures. Curiously, this feature makes Tanuki legends similar to other shapeshifter stories from different countries and nations of the world. In old Chinese and Japanese folklore, Tanuki’s howling on a moonlit night was a portent of bad luck, but occasionally, it could be a good omen.

In traditional Japanese art, Tanuki were often depicted beneath the moon, because a full-moon night was believed to be the time for Tanuki to transform into other creatures. Curiously, this feature makes Tanuki legends similar to other shapeshifter stories from different countries and nations of the world. In old Chinese and Japanese folklore, Tanuki’s howling on a moonlit night was a portent of bad luck, but occasionally, it could be a good omen.

Guarding and hunting

Caverns and tombs that date back to the Bronze Age are often decorated with drawings and statues of dogs (mostly those used for hunting). These animals are even found among ancient children’s toys and as patterns on pottery.Ancient Greeks and Romans valued dogs for their faithfulness and bravery, and preferred them to cats as domestic animals. In Greek and Roman reliefs, dogs symbolised loyalty. Dogs were family pets, guardians, hunters, and indicators of their owners' status. The Greeks appreciated their trust and love. A frequent subject drawn on Greek vases was Odysseus’s arrival at his homeland after his wanderings, and meeting his old dog Argos, the only one who recognised Odysseys and died on seeing his master at last, after years of waiting.

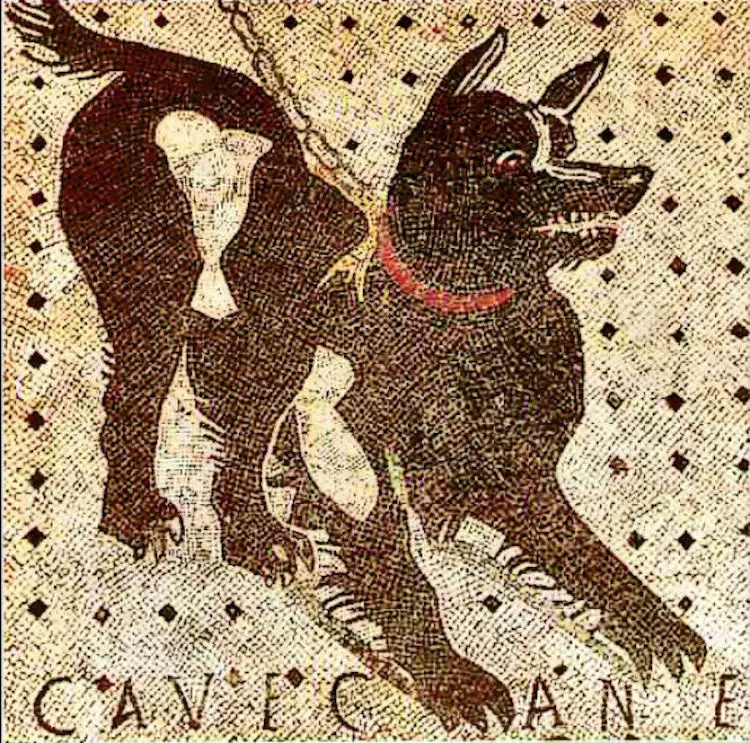

The Romans kept the three kinds of dogs: hunting dogs, mainly sighthounds (the ones most commonly sculpted); large guard dogs, like the Neapolitan Mastiff (their depictions were frequent in reliefs and mosaics bearing the text Cave canem); small toy dogs, like the Maltese, kept mostly by women and almost never found in art of that time. Animals of large breeds were more valued, as they could be used in battles and wolf hunting.

Loyalty and aristocratic status

In the Middle Ages, dogs remained a symbol of fidelity and faithfulness. That is why, along with allegoric subjects, dogs appeared in companion portraits of married couples (typically, by the woman’s side, or on her lap). A dog in a widow’s portrait symbolised her fidelity to her late husband. Besides, these animals were sculptured upon tombstones, in order to praise the dead person’s fealty or spousal constancy.A remarkable example of a dog shown as a symbol is Jan van Eyck's The Arnolfini Portrait. However, different art historians disagree about its role in the picture. On the one hand, the dog in this family portrait may represent marital fidelity, on the other hand, it may symbolise passion, desire, or the couple’s dream of a child. After all, it might have been their real pet, and the painter might have portrayed it to demonstrate the Arnolfini’s welfare.

Medieval art abounds in hunting scenes where people are accompanied by their animals. A picture of a man together with his hunting dogs or falcons was a demonstration of his high social standing, because in those days hunting was an aristocratic entertainment and an obligatory element of the courtly lifestyle. Besides, though agriculture was well-developed, hunting was still an important source of food. The nobility spent fortunes to buy special hound breeds not only for social reasons, but also to provide their families with meat.

The vision of St. Eustace

53×65 cm

Politics and humanism

In the Renaissance period, dogs firmly established themselves in European art. In order to demonstrate their high status, Italian aristocrats of the 16th century often commissioned portraits of themselves in their pets' company. For example, in one of Andrea Mantegna's frescoes in the Camera picta (Mantua), we can see Marquis Ludovico Gonzaga’s favourite dog Rubino, lying comfortably under his master’s seat.Among Renaissance

artists, one of the greatest dog lovers and connoisseurs was Jacopo dal Ponte Bassano. The dogs in his pictures like Adoration of the Magi or The Good Samaritan are so accurate and true to life that there is no doubt Bassano spent a lot of time watching these animals, studying their anatomy and habits.

The adoration of the Magi

1540-th

, 183×235 cm

Good Samaritan

1563, 102.1×79.7 cm

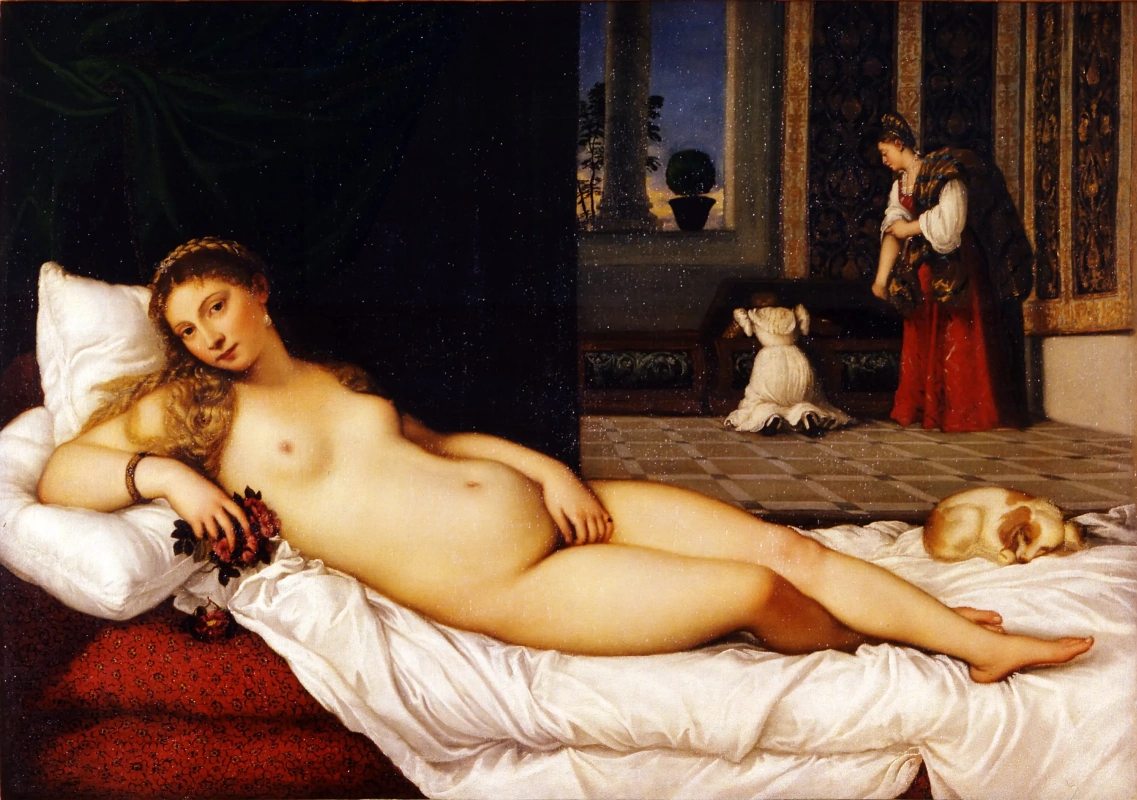

For Titian, too, dogs were of special interest as an artistic subject. They became frequent in his paintings in the 1530s, about the time the artist moved to a large, "status-symbolic" mansion with a garden, and took a few dogs. One of Titian’s most prominent "canine" pieces is the portrait of the little girl Clarissa Strozzi with her toy dog of the Papillon breed. Clarissa, Roberto Strozzi and Maddalena de' Medici’s daughter, was a descendant of two Florentine aristocratic families, and that picture of her was a political matter. The decorations, too heavy for a child, are to signify her noble lineage, but the dog by her side adds an air of childish light-heartedness to the whole picture. The same holds true for the group portrait of the Vendramin family. Here, too, Titian added a note of human feeling and frivolity by placing a dog, again a lemon and white Papillon, on a boy’s lap. And a similar dog is sleeping, curled up, on Venus of Urbino’s bed.

Besides, Titian used dogs as the nobility’s status symbol in his mythological scenes commissioned by Philip II of Spain. One of these illustrates the famous myth of Actaeon. While hunting, he, by accident, saw the goddess Diana (Artemis) bathing. As a punishment, he was turned into a stag and killed by his own hounds. Actaeon’s dog appears in another work by Titian, Diana and Callisto, where it seems to be already the goddess’s property. Hounds are painted in similar poses in all the three versions of Venus and Adonis. Of all mythological subjects, Titian picked these ones because Philip II, his commissioner, was an aficionado of hunting.

Diana and Actaeon

1559, 184.5×202.2 cm

Diana and Callisto

1559, 187×204.5 cm

Venus and Adonis

1554, 186×207 cm

The lifestyle and personal traits

In the 16th and 17th centuries, dogs were mostly painted in hunting scenes or on grand ladies' lap. Some artists, though, portrayed these animals as symbols. For instance, Jean-Léon Gérôme showed the ancient philosopher Diogenes in a company of the dogs, thus alluding to the Cynic school of thought (from the Greek word κύων meaning "dog"). Antisthenes, who is regarded as the founder of this school, believed that to gain happiness, one should live "like dogs" — follow one’s nature, be able to defend oneself, be loyal, brave, and noble-minded. Diogenes was one of the most ardent adherents of Cynicism, and on the philosopher’s grave, a monument with a sculpture of a dog was even placed.As early as in the Renaissance

, standards of dog breeds started being developed and established. The 18th century witnessed the appearance of dogs' portraits in their own right. Sometimes, these portraits had absolutely extraordinary stories behind. For example, in 1831, Edwin Landseer portrayed a Newfoundland dog called Bob. That huge animal had been rescued in a shipwreck off the coast of England, and found his new home in the London waterfront. Bob, too, became a rescuer: over the course of fourteen years, he saved more than twenty people from drowning. For this, he was made a distinguished member of the Royal Humane Society, granted a medal and access to food. Since then, a particular breed with black and white colouration, related to Newfoundland dogs, has been called the Landseer.

A worthy member of a humane society

1831, 111.8×143.5 cm

P. S.

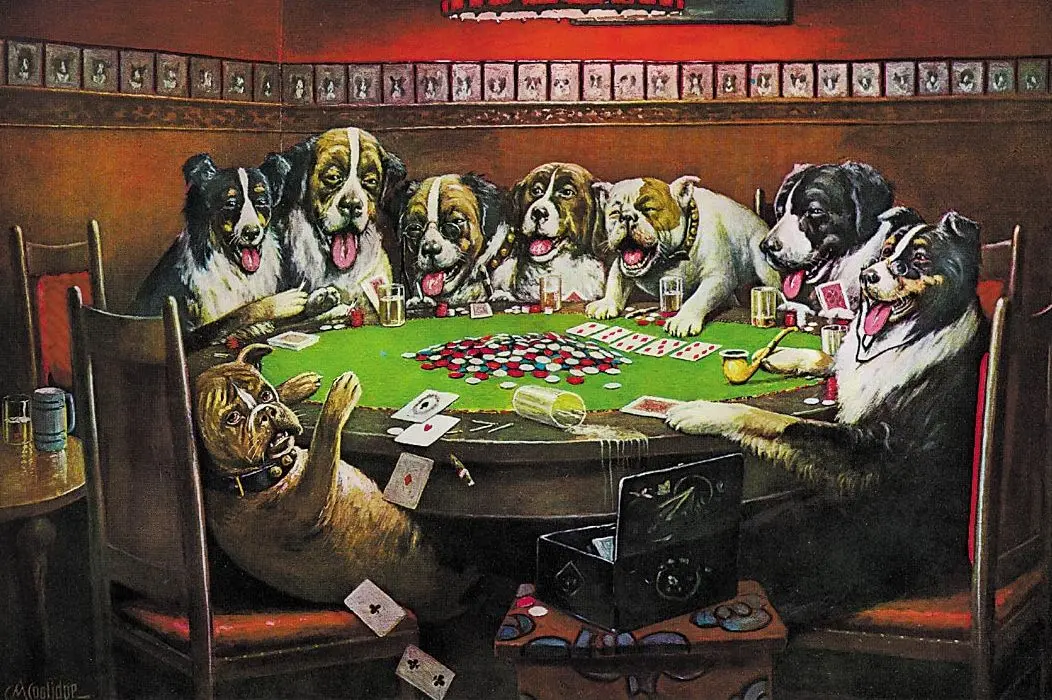

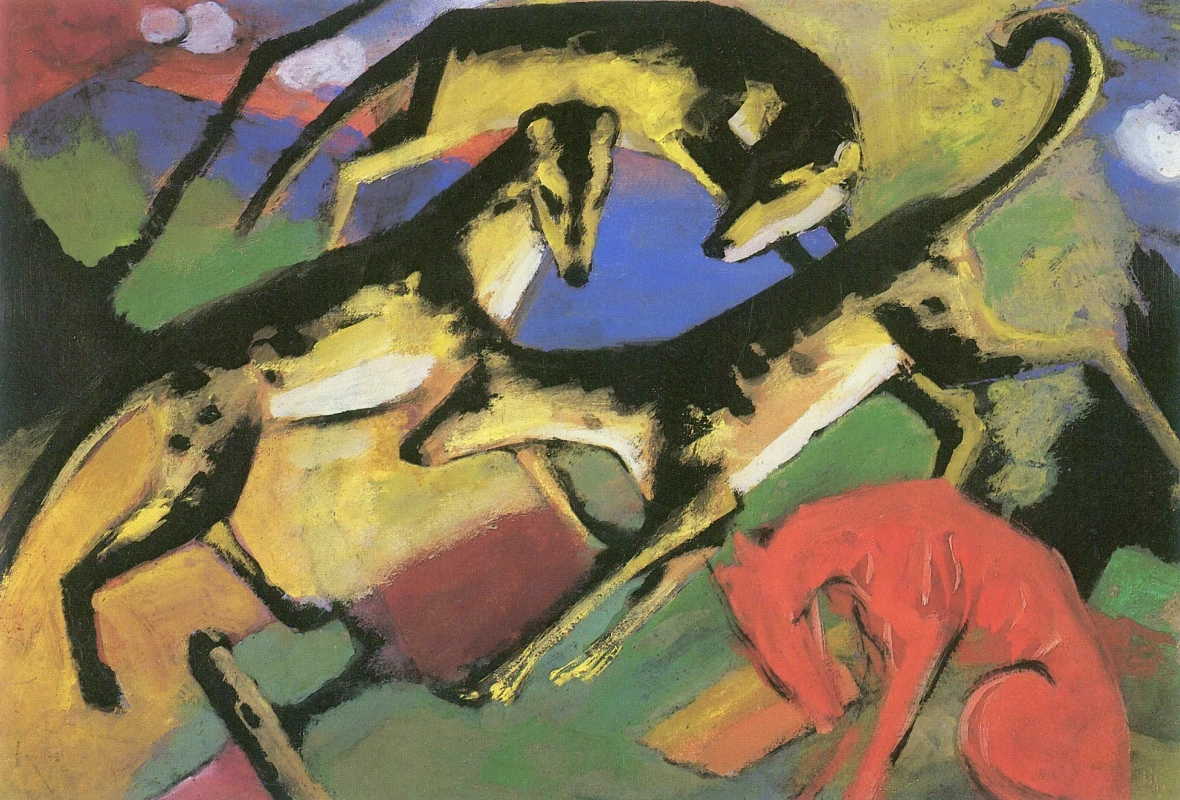

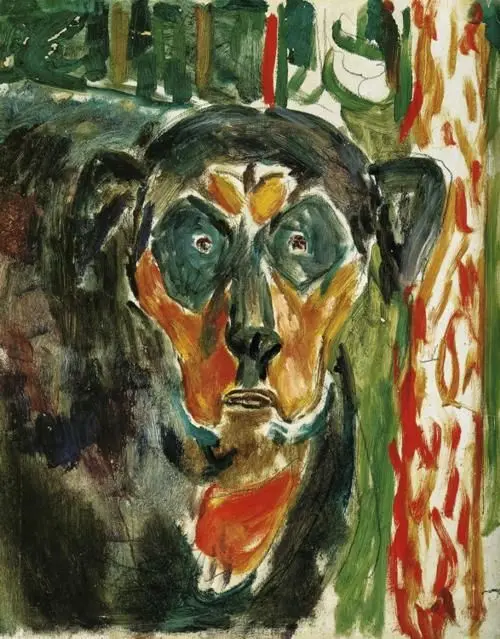

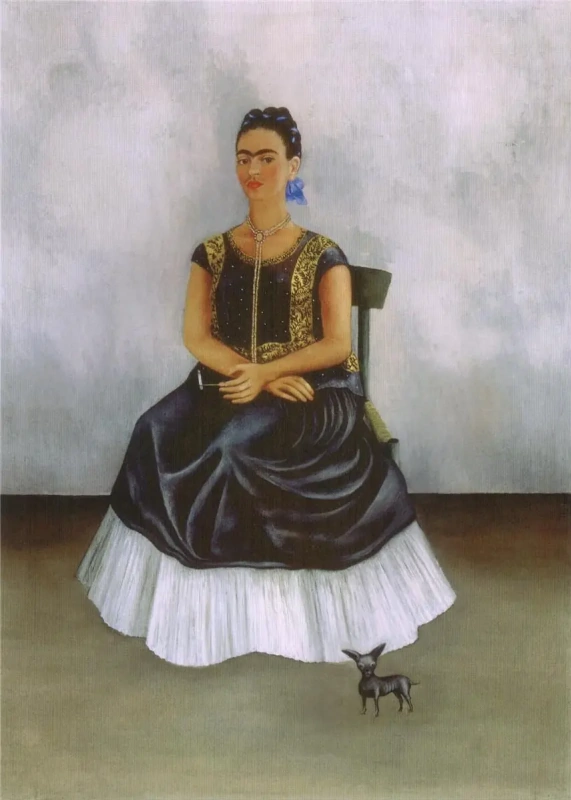

The 20th century, marked with rapid changes and stylistic diversity, presented dogs in a great many new images. Cassius Marcellus Coolidge "humanised" dogs by showing them seated round a table and playing poker. Franz Marc, who, besides horses, had other favourites, too, used his singular brushwork to paint sleeping and playing dogs. David Hockney created innumerable portraits of his dachshunds. Edvard Munch, Frida Kahlo, Andy Warhol, and Lucian Freud portrayed their pets, too.In a way, the art of the 20th century, much more often than it was before, foregrounds an artist and his personality. So any subject an artist chooses (including depiction of a dog) characterises its author rather than has a symbolic message of its own.

Title illustration: Gerrit (Gerard) Dou. Sleeping Dog. 1650

Artistes mentionnés dans l'article