Separation and affirmation

A falling shadow is almost never found in medieval art, while if the subject still required it, it was presented conditionally, since the artists of that time did not yet know the perspective and even more so the volume, the secret of which was only revealed in the Renaissance . Then they began to actively use the shadow to make the image realistic.

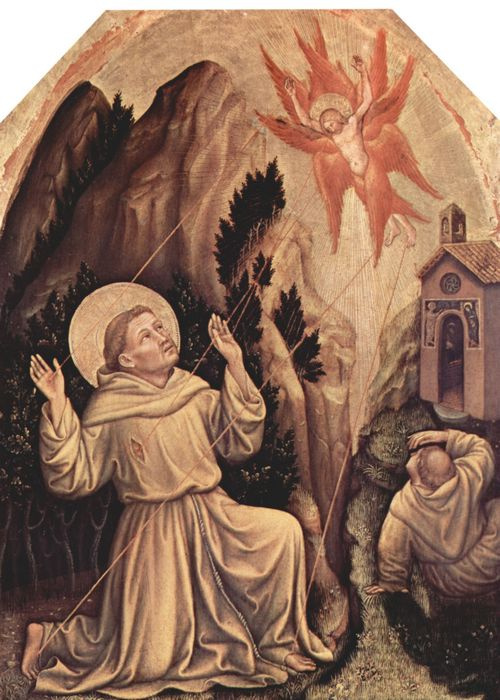

In 1410 Gentile da Fabriano painted the Saint Francis Receiving the Stigmata (1419) panel: the incident light illuminates a small section of the mountain, gets scattered by trees and effectively reflects the silhouette of the Saint on the ground.

The Middle Ages was the period that discovered the beauty and poetry of light in painting, whereas the Renaissance revealed the beauty and poetry of the shadow in art; while the light, on the contrary, was discredited. Moreover, in medieval painting light acted as a positive, creative beginning, whereas in the Renaissance, such a formative, positive beginning was the shadow.

In the 18th century, the aesthetics of the dark and ominous developed in art, and the shadow began to play an active role of a negative principle. This was embodied in the works by Francisco de Goya (Yard with Lunatics, 1794), Heinrich Wilhelm Tischbein, Joseph Wright of Derby, and others. Artists and writers were inspired by everything mysterious and dark.

From light games to mind games

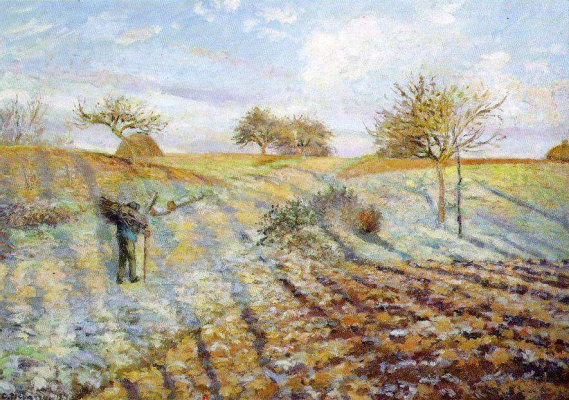

The Impressionists lost interest in the shadow’s narrative capability and used it exclusively as a visual element. In the early works of Claude Monet, the shadows of trees are still depicted black, whereas in the later paintings of Camille Pissarro (Rime, 1874) and Alfred Sisley, the traditional black colour disappears, the shadows become coloured, and gradually their negative meanings disappear.

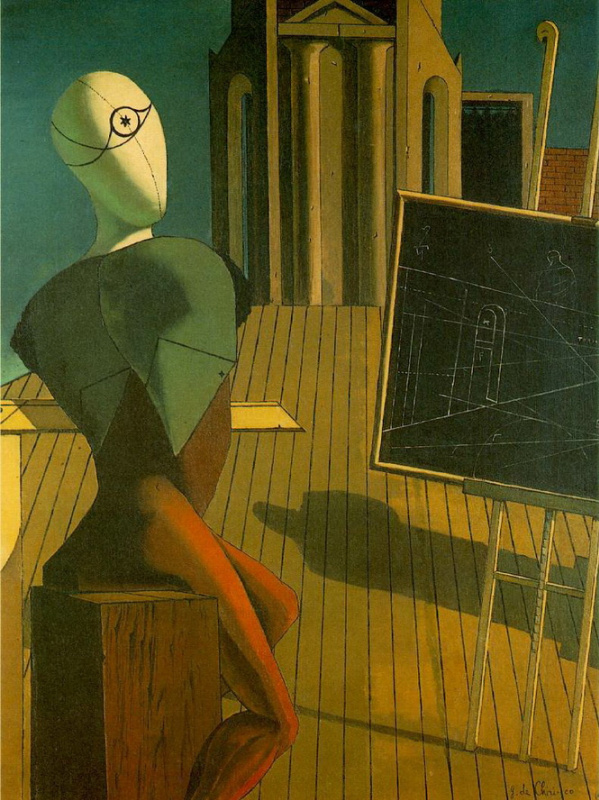

In the art of Giorgio de Chirico, the shadow becomes an obsessive image of the night darkness, any darkness of obsessive fears, darkness of the soul, its behaviour is unpredictable and not subject to the laws of perspective. It appears unmotivated in de Chirico’s paintings, out of nowhere (The Prophet, 1917). In the metaphysical world of ideal entities, the eternal day reigns.

In many realistic canvases, the shadow returns to its vocation and expresses gloomy moods. In the Portrait of Dr Haustein (1928), Christian Schad used shadow to depict a scene of the conversation (the character’s counterpart is reflected on the wall).

Among all modernist trends, the surrealists attached the greatest importance to the shadow. This is partly due to their interest in depicting dreams and fantasies. Salvador Dalí, Yves Tanguy, René Magritte and Paul Delvaux tried to portray their fantasies more realistic than reality itself; for this purpose, they carefully painted every detail and constantly used shadows.

In the realistic painting of the 20th century, the ability of the shadow to create a mood of universal loneliness was actively used (Edward Hopper, Rockwell Kent, Felix Nussbaum).

The Pop Art King. Andy Warhol dedicated a series of his artworks to the shadow. Thus, he wanted to separate his image and the body. The Shadow (1981). Later, Ed Ruscha, Gerhard Richter and others used shadow as a pictorial means in their work.

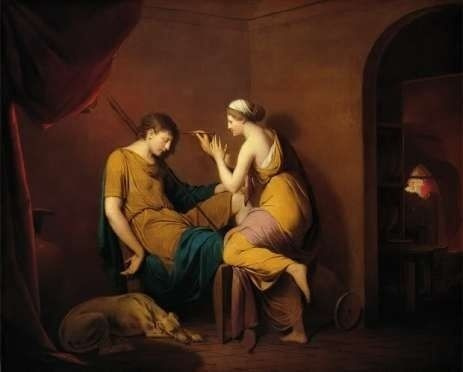

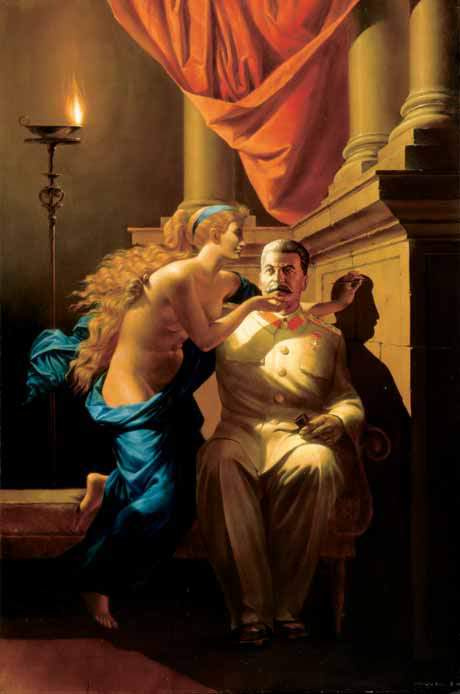

The Origin of Socialist Realism (1982—1983), the painting of Russian contemporary artists Vitaly Komar and Alexandr Melamid presents an ironic vision of the classical myth associated with the traditions of socialist realism.

Finding independence

Today, the creation of works through the use of shadow is gaining popularity, and objects casting a shadow, as a rule, have nothing to do with the result obtained. To create their works, artists turn the lights on and off for months, moving simple materials (paper, wood, aluminium, various rubbish). For example, the favourite theme of the Greek artist Teodosio Aurea is the beauty and grace of the female body.

The English painter and sculptor Rook Floro portrayed the drama of a man devoid of integrity. The character is torn in two: one is who he is, the other is who he could be. It might seem that a tall figure should cast a shadow, but it is somewhat amorphous, and black needles stick out from the character’s back. The main thing in sculpture is that both parts are united by the shadow itself, a dark path. Thus, in the hands of the artist, the secret becomes apparent.

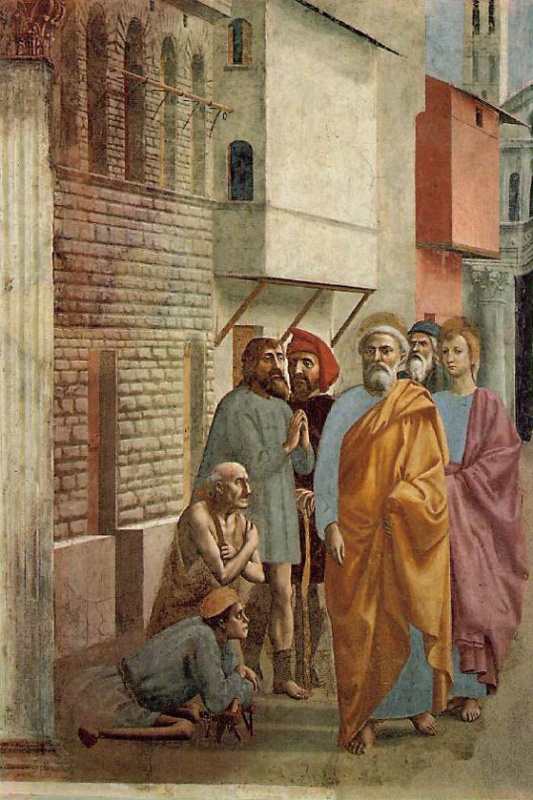

From now on, artists become the creators of light, and the first great artist of the 15th century, Masaccio, makes the shadow the core of his painting composition of the Brancacci Chapel (St Peter Healing the Sick with his Shadow, 1424—1425), a source of divine grace. In medieval painting, God and Saints were depicted in a halo of light, whereas in the Masaccio’s fresco, the Saint appears in a halo of shadow.

Moreover, in the Renaissance, the shadow acquired an additional, symbolic meaning associated with the theme of the Annunciation. In the works by Jan van Eyck, Lorenzo di Credi and Ludovico Carracci, the shadow cast by the Archangel Gabriel on the Virgin Mary symbolizes the "shadow of the Almighty", by Whose power Jesus Christ was embodied as a man.

The sacred darkness

Leonardo da Vinci paid much attention to the role of light and shadow in the visual arts. For the great Leonardo, a painting is a shadow of a human shadow, in contrast to medieval painting that sought to depict the light of the Lord’s light. For him, the dark acts as the embodiment of the earth, the earthly principle, the image of the depth of the earth’s interior. Leonardo does not like bright light, "excessive light creates coarseness", exposes, insults this secret of the living hidden in the twilight. For him, the shadow is the embodiment of the mystery and poetry of life.

Michelangelo Merisi de Caravaggio used the shadow as an independent philosophical image in his work. On his canvas, Supper at Emmaus (1601), which depicts the meeting of the apostles with Christ after his death, the shadow over the head of Christ repeats the shape of the halo, but not the colour. Few could dare to break the centuries-old tradition and deprive the halo of the symbolism of heavenly light. In the picture, everything is extremely mundane, and the spoiled apple reminds of the original sin. The history of Christ is purely experienced from the point of view of a human destiny, and the black shadow turns into a symbol of Doom.

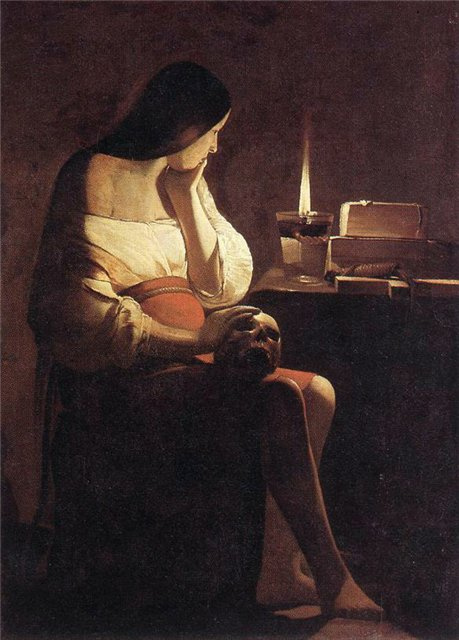

For Baroque artists such as Jean Leclair, Matthias Stom, Hendrick ter Bruggen, Georges de La Tour and others, the shadow becomes the embodiment of the sacred in everyday life. The contrasting night lighting lends a deep drama to religious compositions. The intense light not only emphasizes the energetic plasticity of forms, the purity of silhouettes, but also evokes a feeling of mystery hidden in real life. This is especially evident in the paintings by Georges de Latour. In his Magdalene with the Smoking Flame (1630), a bright candle flame spreads its light in the empty space of the room, plunging the young woman into endless silence, an atmosphere of deep mysticism and quiet melancholy. The candle conveys the theme of the struggle between light and shadow. Latour shows the "night" — the emptiness of the human soul, which can only realize itself through the light of faith.