Chinoiserie (fr. chinoiserie — Chinese-like, derived from chinois — "Chinese") is a stylization genre that imitates the works of art and architecture by oriental masters, one of the varieties of Orientalism. The direction is a European interpretation and imitation of the artistic traditions of the artists of China and East Asia, mainly in decorative art, garden design, theatre, and music. Chinoiserie aesthetics appeared in the 17th century and became even more popular in the 18th century thanks to the vigorous activity of the East India Trading Company and European trade with the countries of the Far East.

Characteristic features of the chinoiserie style

The chinoiserie style has much to do with the rococo style: both have intrinsic abundant decor, asymmetry, emphasis on materials, as well as they both focus on stylization and the theme of pleasant relaxation and enjoyment. Chinoiserie focuses on the subjects which the colonial-era Europeans considered typical of Chinese culture. Artists from England and Italy, and later from other European countries, obeying oriental exoticism, began to freely use the decorative motifs from furniture, porcelain dishes and fabrics imported from China. Intricate patterns with dragons, phoenixes, flowers, oriental landscapes could be found on fans and sun umbrellas, on snuffboxes, tapestries and wallpaper.

François Boucher. Chinese Emperors Feast. Museum of Art, Besançon

The starting point

The impulse for the chinoiserie style prosperity was the illustrated encyclopaedia of China, compiled by a German monk, scientist and inventor Athanasius Kircher (1602—1680). His work China illustrata ("Illustrated China") was published in 1667 in Amsterdam, and it based on the stories by Jesuit monks from the Chinese mission of the order.

Frontispiece of the China illustrata book by Athanasius Kircher, 1667. Source

This compilation of Chinese and Indian culture and traditions aimed, first of all, to demonstrate the prevalence of Christianity in the East. It reflected the success of the Jesuit Order in their missionary work. Nevertheless, there was a place for the animal and plant world, ancient monument studies, lifestyle, political system and other aspects of the Oriental life in the book. The rich illustrations of this primarily scientific publication led to its great popularity, and by the end of the same year a second edition was published. Two years later, the China illustrata was translated into English by John Ogilvy in a truncated format.

Tea bush. Illustration from China monumentis by Athanasius Kirchner: "A. Cia sive Te Herba", 1667. Source

Chinoiserie: decor and porcelain

Chinese porcelain won over European aristocrats and became an undeniable sign of family wealth. Elegant, light, beautifully painted dishes became an integral part of tea ceremonies in every fashionable living room, and decorative vases adorned the interiors of the nobles and royal palaces. In 1708, a porcelain recipe was reproduced in Saxony, which had been considered the greatest Chinese secret until then, and in 1710 the first porcelain factory opened in Meissen. In the early years of the work, craftsmen and artists used Chinese products as samples, which were in great demand. Rich people began to form their own porcelain collections.

François Boucher. Morning Tea Party

Chinoiserie in architecture

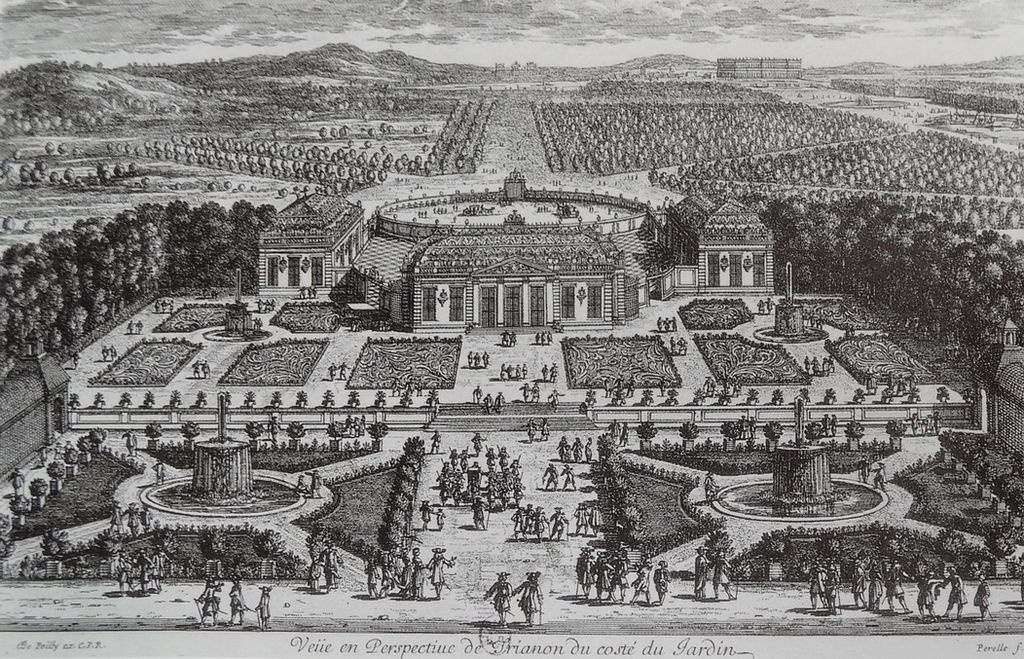

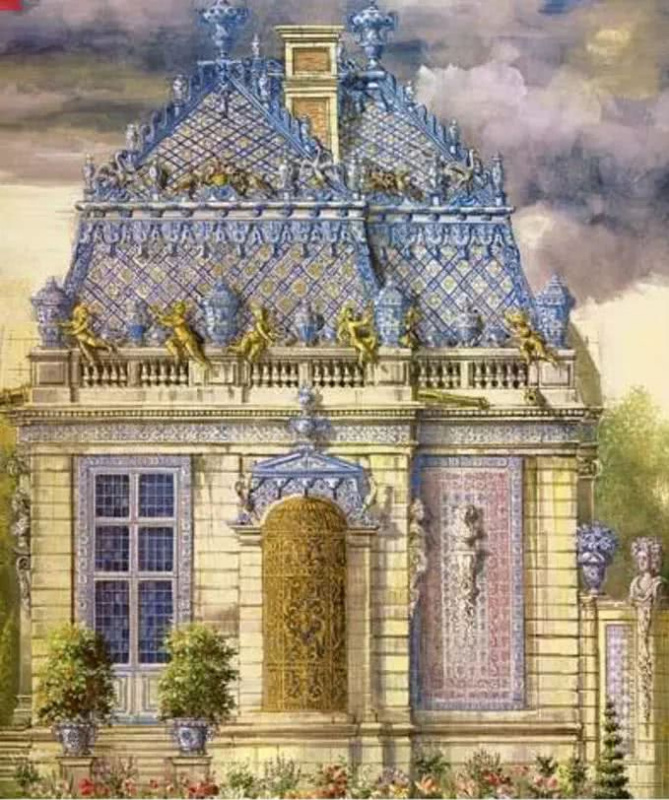

The first significant chinoiserie architectural complex, the Porcelain Trianon (fr.: Trianon de porcelaine), was created in 1670 in the village of Trianon, near Versailles, for King Louis XIV of France. The light-framed buildings were lined with white and blue ceramic tiles painted in oriental style. It is assumed that this solution was a tribute to the exciting stories from Kirchner’s book about the famous Nanjing Porcelain Tower, which was considered the eighth wonder of the world. Of course, the tiles were made of earthenware, while the roof was decorated with painted earthenware vases and figures of cupids. The buildings of Trianon were surrounded by a beautiful garden, the outlines of which have survived to this day. The Porcelain Trianon, the shelter of Louis XIV and his mistress Marquise de Montespan, did not stand long: it was demolished in 1687, and the Marble Trianon was built instead.The quirk of the French king quickly spread throughout the European royal courts. Since then, almost every royal residence has always had its own "Chinese room", a living room or an office. They combined Chinoiserie with baroque

and rococo, richly gilded or varnished decorative elements and decorated with inlays and carvings. The classic colour palette was white and blue, oriental figures and motifs were combined into asymmetric compositions with the planar perspective inherent in oriental art.

William Chambers (1723−1796), the son of a Scotch merchant, studied Chinese architecture in detail during his three trade trips to China in the 1740s with the Swedish East India Company. Having become an architect, Chambers successfully adapted his ideas to the English Palladio style and became the chief architect of the establishment. His friendship with George III helped him to become eventually the Surveyor-General and Comptroller — in fact, the architect of the Crown. Chambers became the first European to conduct methodological studies of Chinese architecture and publish them in his original work, Designs of Chinese Buildings, Furniture, Dresses, Machines, and Utensils. The most famous surviving building created by Chambers is the Kew Royal Botanic Gardens pagoda.

The architectural complex in the Kew Royal Botanic Gardens: Chinese pagoda, Turkish mosque, Alhambra. Architect William Chambers (1723−1796). Source.

The Chambers Pagoda is almost 50 metres high. It was built at the peak of European interest in the culture of the Far East. The construction of the 10-storey pagoda lasted less than a year, and its height was so stunning that Chambers' contemporaries often wondered if it could remain standing at all. The roof corners were decorated with 80 carved dragons, which were removed a few years later, as the wood rotted. In 2018, after reconstruction, the dragons were returned to the roofs — the upper figures were made with a 3D printer, and the lower eight figures were hand-carved by English craftsmen.

The Great Pagoda at the Kew Royal Botanic Gardens after restoration in 2018. Source

Rococo, chinoiserie and artists

In fine art, the chinoiserie style is most widely represented in the works by French painters Antoine Watteau (1684 — 1721) and François Boucher (1703 — 1770). Watteau’s works resemble the details of traditional porcelain painting. Fantastic, similar to the Versailles festivals, the theatrical paintings by Boucher represent the European view of China, its inhabitants and traditions, Rococo in an oriental manner.Chinoiserie greatly influenced fashion. Dresses made of natural silk became great chic. Oriental motifs in dresses were reflected not only in stylized embroidery, but also in sleeve fit, the so-called pagoda sleeve. Aristocrats received guests in step-in slippers — mule shoes, which Marie Antoinette later made an indispensable element of everyday fashion.

The portrait of the artist François Boucher’s wife, Marie-Jeanne Busot, shows chinoiserie in almost every detail: pagoda sleeves, mule shoes, a Chinese-style screen, an elaborate shelf with a china tea set and a Chinese figurine on the wall.

The portrait of the artist François Boucher’s wife, Marie-Jeanne Busot, shows chinoiserie in almost every detail: pagoda sleeves, mule shoes, a Chinese-style screen, an elaborate shelf with a china tea set and a Chinese figurine on the wall.

Portrait of Marie-Jeanne Busot, the artist's wife

1743, 57×68 cm

Boucher not only portrayed vivid scenes from the life of China (certainly, in the European manner), but also adored everything oriental, and also collected outlandish original decorative gizmos from China and Japan. His collection was auctioned in 1771, a year after the artist’s death. He also created a collection of cartoons in chinoiserie style for the Beauvais tapestry manufactory.

François Boucher. Cartoon for tapestry "Chinese Wedding"

Chippendale, the cabinetmaker in chinoiserie

The brilliant English cabinetmaker, Englishman Thomas Chippendale (1718—1779), was famous not only for his furniture, but also left to his descendants The Gentleman and Cabinet-Maker's Directory — a classic book with engravings of the products of his own workshop. Chippendale’s Rococo furniture and picture frames with Chinese and Gothic elements formed the basis of the "English" Rococo. Another book that influenced chinoiserie style was New Designs for Chinese Temples (1750) by the architect William Halfpenny.

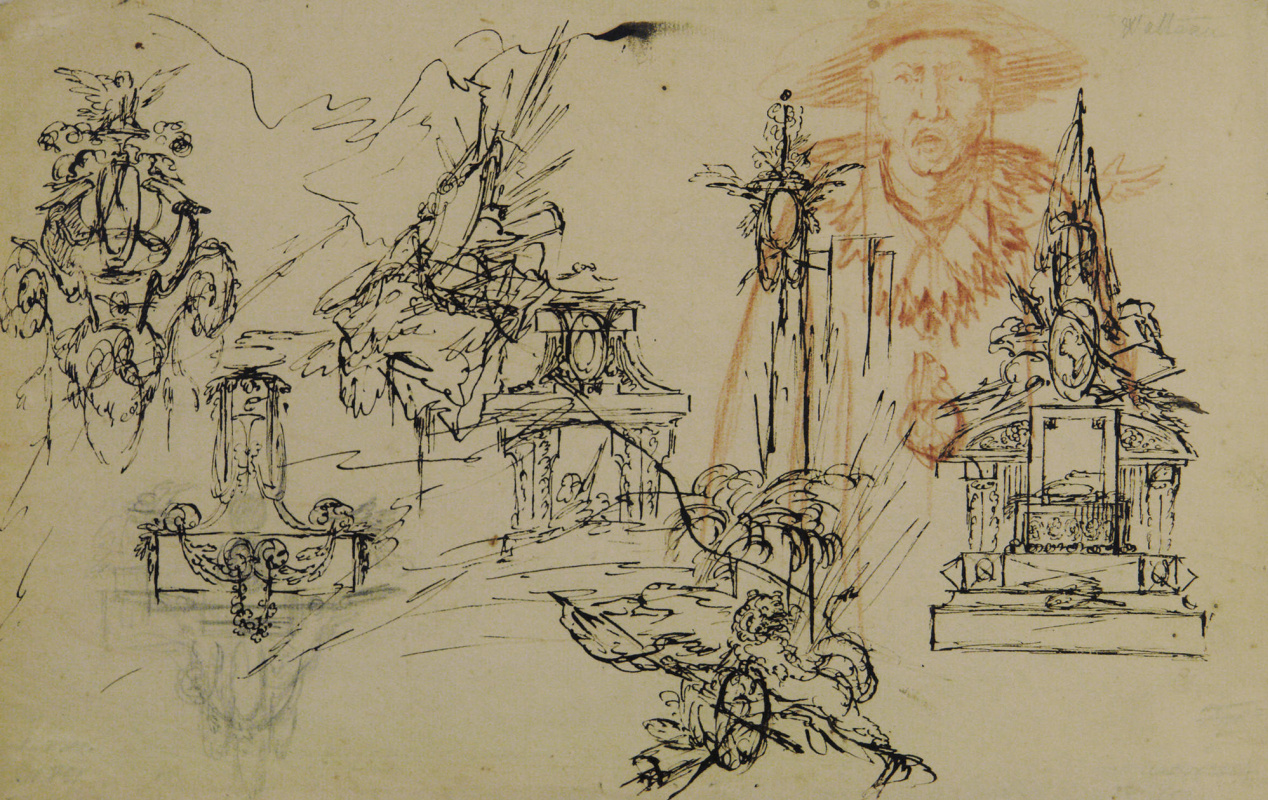

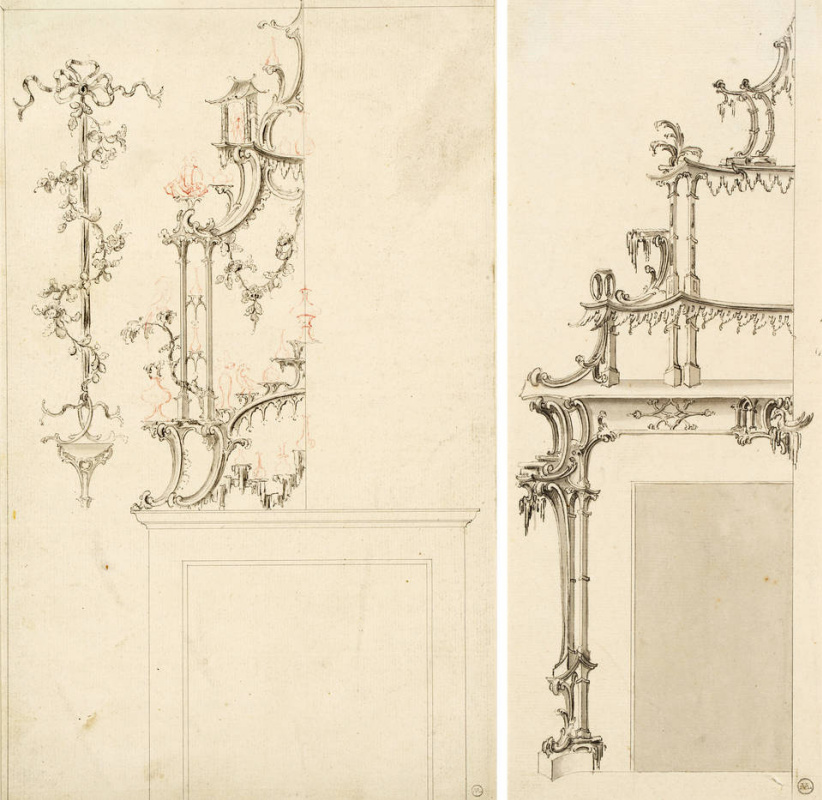

Thomas Chippendale. Design for part of an overmantel and a wall bracket, about 1760.

On the right: a design for decorating a fireplace, about 1760. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Folding screens were one of the most popular decorative elements of the interior; they were adorned with drawings in the Chinese style. Among the fashionable subjects, there were sketches of palace life, birds, flowers, landscapes and romantic scenes from Chinese literature.

Woman fastening her garter, with her maid

1742, 53×67 cm

The Chinoiserie style was in fashion in Russia as well. The Chinese blue room was made in the Catherine Palace, it combining classic interior elements with rich painted silk wallpaper brought from China. And in 1762, Antonio Rinaldi built the Chinese Palace for Catherine II, which was a part of the architectural ensemble of Own Cottage in Oranienbaum. Several halls of the Chinese palace are decorated in chinoiserie style.

Chinoiserie remains a fashionable design trend to this day. Bizarre, fantastic landscapes and playful colours help to create interiors within the decorative aesthetics of the Orient.