The identity of Leonardo da Vinci's mother has always been a mystery. Art historians struggle to find information about the woman whose illegitimate son became the artistic genius who painted Mona Lisa. One of the world’s leading authorities on Leonardo, Martin Kemp, in his book shed more light on the mysterious figure and her fate.

With only a possible first name — Caterina — there has been speculation that she was a peasant or even a slave from North Africa.

From: Getty Images

Now, almost six centuries later, one of the world’s leading authorities on Leonardo has given a far fuller account of her story, using documents overlooked by other scientists. According to Martin Kemp, emeritus professor of art history at Oxford University, the future artist was born by Caterina di Meo Lippi, a poor and vulnerable orphan. She had been living with her grandmother in a decrepit farmhouse, about a mile from Vinci. The girl was only fifteen when she was seduced by a lawyer.

Kemp makes his claims in a book out next month, Mona Lisa: The People and the Painting, written with Dr Giuseppe Pallanti, an economist and art researcher.

Newly unearthed documents also cast light on the famed Lisa del Giocondo, and her husband, Francesco. Far from being a genteel Florentine silk merchant, as previously supposed, he was ‘a sharp operator', trading in sugar from Madeira, leather from Ireland, property — and slaves. Kemp believes so, judging from evidence of regular purchases of female slaves.

Left: Leonardo da Vinci. Mona Lisa (Gioconda). 1500s. Louvre, Paris

The research also challenges the generally recognised site of Leonardo’s birth, on 15 April 1452 — the so-called Casa Natale in Anchiano, two miles from Vinci. The Casa has become a museum and a place of pilgrimage for tourists, but documents suggest that art lovers have been visiting the wrong site. Kemp believes the birthplace was more likely to have been the house of his paternal grandfather in Vinci, where Leonardo grew up.

Madonna and child with St. Anne and John the Baptist

1499, 141.5×104.6 cm

The new insights follow a trawl through fifteenth-century financial documents held within the archives of Vinci and Florence. They have proved a goldmine, having been overlooked by other art historians.

Much of the new evidence comes from property taxation returns. As is seen from inspectors' records, Caterina’s father, who seems to be pretty useless, had a rickety house which wasn’t lived in and they couldn’t tax him. He had disappeared and apparently died young. Besides, Caterina had a stepbrother, Papo. Her grandmother died shortly before 1451, leaving them with no assets or support, apart from an uncle with a ‘half-ruined' house and cattle.

Professor Martin Kemp says, Caterina’s was a real sob story. Photo by: David Levenson / Getty

According to Kemp, Caterina was seduced by 25-year-old Piero da Vinci, an ambitious lawyer working in Florence. In July 1451, he stayed in the country. The lawyer was due to get married to another woman, and his family might have provided Caterina with a modest dowry. This can explain how — with no means or possessions — she was married off quickly to Antonio di Piero Buti, a local farmer ‘from her own stratum of society'.

Leonardo was nurtured in the nearby house of his grandfather, Antonio da Vinci. Such arrangements were not uncommon then, Kemp says. Antonio’s 1457 tax return lists family members, including Piero’s illegitimate son, as ‘born of him and of Caterina'.

Leonardo was nurtured in the nearby house of his grandfather, Antonio da Vinci. Such arrangements were not uncommon then, Kemp says. Antonio’s 1457 tax return lists family members, including Piero’s illegitimate son, as ‘born of him and of Caterina'.

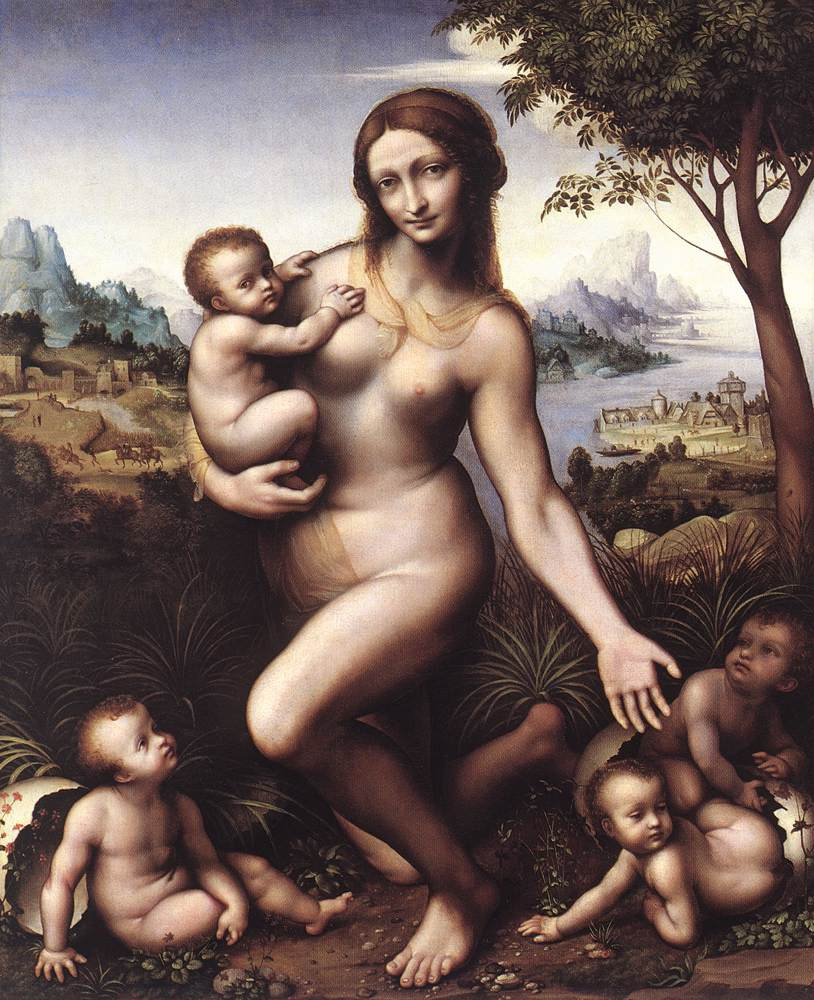

Leda

1500-th

Caterina went on to have a second son and four daughters. Documents reveal a further link between the lawyer and Caterina: he conducted a minor legal transaction for her husband.

Kemp hopes his work will put an end to ‘totally implausible myths' that have built up about Leonardo’s life. Many find attractive the theory of Caterina being a slave, an African, or even an Oriental one. It stems from the fact that Caterina was a name commonly given to slaves.

Above: Famed female portraits by Leonardo da Vinci — Lady with an Ermine (1480s), and La Belle Ferronnière (1490s)

Besides, Kemp’s book pokes fun at his colleagues who try to make their name with new theories about Mona Lisa — that she is Leonardo in drag, or she is a ‘lady of the night'. As he says, ‘the legends become more true than the truths.'

But why had so many significant documents been ignored until now? That is how Kemp explains it, ‘Archives are not tackled because, in current academia, you need to get quick results rather than slogging through material with no guarantees of returns.'

But why had so many significant documents been ignored until now? That is how Kemp explains it, ‘Archives are not tackled because, in current academia, you need to get quick results rather than slogging through material with no guarantees of returns.'

Virgin of the rocks (Madonna of the grotto)

1508, 189.5×120 cm

Title illustration: Leonardo da Vinci. The Madonna of the Yarnwinder. 1507. Private collection

Based on The Guardian publication

Based on The Guardian publication