Nowadays smile is an expression of joy and happiness. But what about real emotions behind the smile? They can have a variety of meanings. Now we turn to art to see how smile varied in the long history of portraiture.

Throughout history, the smile was analogous to foolishness, irrational emotion, and deceit.

According to art historian Colin Jones from Queen Mary University of London, the point of inflection regarding the public opinion of smiling came about with a controversial self-portrait of Madame Elisabeth-Louise Vigée Le Brun. In her painting Le Brun, a young mother, portrays herself smiling ever so slightly, showing the edges of her teeth.

"Madame Vigée-Le Brun et sa fille (1786)" by Louise Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun

"It was an innovation that was most unwelcome. No one had been doing this thing since antiquity. If teeth appeared in a portrait, it was usually because the person being portrayed was plebian… or not in full command of their rational faculties."

Beginning from the 20th century the diffusion of smiling in art increased. With the advent of photography and cinema it turned into a habit. The smile has always been considered the stage of internal motions and secrets of the human soul, revealing happiness, fun, seduction, cunning, satisfaction, but also commiseration or uncertainty and, at times, uncomfort. Nowadays, smile becomes a widespread, popular cultural phenomenon.

"A smile doesn’t necessarily mean happiness; it could be something else. In China there’s a long history of the smile — Mr. Yue said — There is the Maitreya Buddha who can tell the future and whose facial expression is a laugh. Normally there’s an inscription saying that you should be optimistic and laugh in the face of reality." But some experts on Chinese art suggest that Mr. Yue’s grin is a mask for real feelings of helplessness.

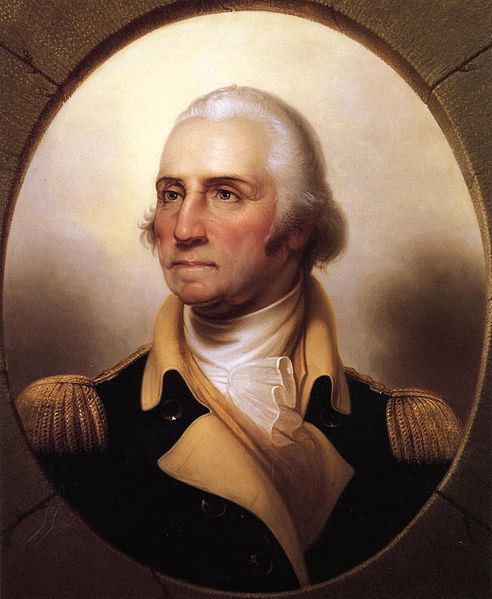

The 18th century, Age of Enlightenment, gave more place to smiles in portraiture, even if teeth were still kept hidden behind a close mouth. The ambition was not to capture a moment, but a moral certainty. Smiling also has a large number of discrete cultural and historical significances, few of them in line with our modern perceptions of it being a physical signal of warmth, enjoyment, or indeed of happiness. Politicians were particularly sensitive to this.

In the few examples we have of broad smiles in formal portraiture, the effect is often not particularly pleasing. In this sense, a portrait was never so much a record of a person, but a formalised ideal.

To see the smile at its biggest and best, we have to leave the upper classes and instead visit our attentions on those lower in the social order. 17th century Dutch painters were fascinated with recording the fullness of life, and deliberately sought out the smiles found within it. Here there are almost no end of artists to choose from, and in consequence ‘Dutchness' in painting, and in life, was often a society shorthand for licentiousness. Jan Steen, Franz Hals, and Judith Leyster were all followers of this style, all painted broad smiles, and all were said to be good company, there being no attempt at separation between the artist, the viewer, and the subject.

By the 17th century in Europe it was a well-established fact that the only people who smiled broadly, in life and in art, were the poor, the lewd, the drunk, the innocent, and the entertainment. Showing the teeth was for the upper classes a more-or-less formal breach of etiquette.

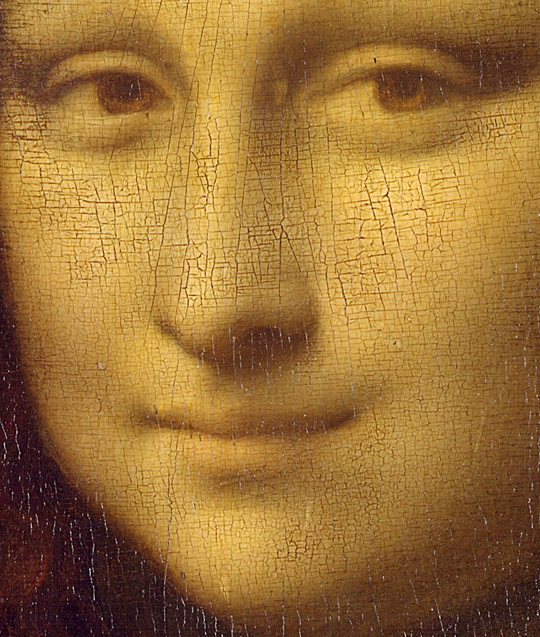

In the 16th century artists often used the technique in which the mouth in portraiture has been debated: an ongoing conflict between the serious and the smirk. The most famous and enduring portrait in the world functions around this very conflict — Mona Lisa by Leonardo da Vinci. Millions of words have been devoted to the Mona Lisa and her smirk — more generously known as her "enigmatic smile".

Mona Lisa (La Gioconda)

1500-th

, 77×53 cm

Equivocal "smirks" do however make more frequent appearances: a smirk may offer artists an opportunity for ambiguity that the open smile cannot. Such a subtle and complex facial expression may convey almost anything — piqued interest, condescension, flirtation, wistfulness, boredom, discomfort, contentment, or mild embarrassment. This equivocation allows the artist to offer us a lasting emotional engagement with the image. An open smile, however, is unequivocal.

Sicily’s Antonello da Messina was surely considering all this when he painted what we now know as Portrait of a Man. Antonello painted quite a few portraits with smiles, and the subject seemed to interest him. We might even infer that it was the challenge of painting a smile in a new tradition that motivated him, being a pioneer by nature. Messina did not go quite so far as to show the teeth, though gave him long dimples on his cheeks and laughter lines at the corners of the eyes.

In the Middle Age, smiling was considered as a mask of childish behaviour.

However, here the smile has a non-human significance, being the character a divine entity.

However, here the smile has a non-human significance, being the character a divine entity.

The Archaic smile appeared on sculptures in the second quarter of the 6th century BC. This smile was used by Greek Archaic artists. It is noted as a small smile or smirk on the face of the sculpture.

It is supposed that this smile was created to suggest that the subject of the sculptor was alive and in good health.

It is supposed that this smile was created to suggest that the subject of the sculptor was alive and in good health.

Limestone male head, late 6th century BC

A walk around any art gallery will reveal that the image of the open smile has, for a very long time, been deeply unfashionable. Nowadays each of us is recorded across hundreds of images, and many of us are smiling broadly. Collected, they represent us accurately in all our moods and modes, and it’s perfect opportunity no longer to worry about being defined by one picture.

Based on materials from The Guardian, The New York Times, Art News, official site of the Louvre Museum

Title illustration: detail from Leonardo da Vinci’s La Gioconda (Mona Lisa), 1503−1506

Title illustration: detail from Leonardo da Vinci’s La Gioconda (Mona Lisa), 1503−1506