Varvara Nykolayevna (1852—1922) grew up in an atmosphere of piety and passion for art, and she was not inferior to her brothers in terms of passion for collecting. In the person of Bohdan Ivanovych Khanenko (1849—1917), she met a like-minded person close to her in spirit. The husband graduated from Moscow University in 1871, served as a magistrate in St. Petersburg, then a member of the Warsaw District Court, served in the Department of Justice. He was interested in art, met Shishkin, Kuindzhi, Aivazovsky, and began collecting paintings early.

Trial and error method

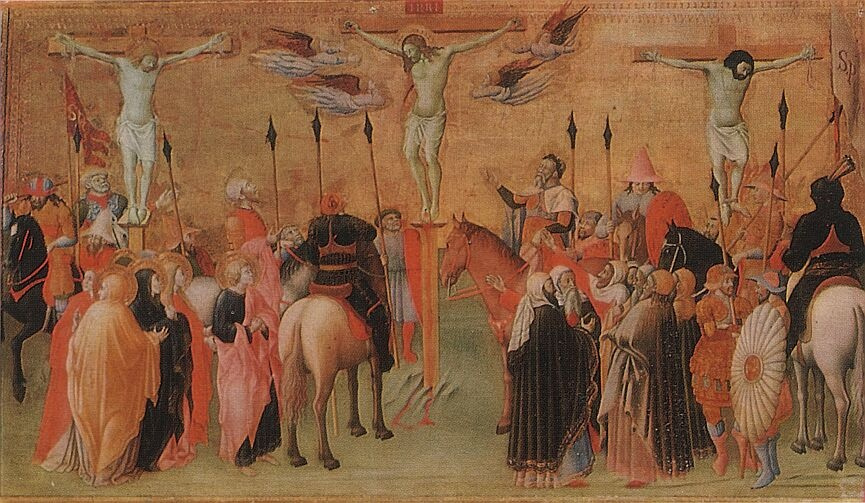

Bohdan Ivanovych collected artifacts with the passion of a hunter. Thanks to his instinct, in Kyiv, you can see the works of Rubens, Pieter Brueghel the Younger, Van Eyck, Perugino, Frans Hals, Reynolds, and the Khanenko Adoration of the Magi diptych by an unknown Dutch artist of the 15th century, which entered all world catalogues.Olena Zhyvkova, deputy director for scientific work of the Bohdan and Varvara Khanenko National Museum of Arts, tells the story of one acquisition. Moscow horse breeder Malyutin asked Khanenko to urgently come to him so that he would take away unnecessary trash from him. The time was late, and he had to examine the canvases with a candle. But even under dim lighting and a cursory examination, the instinct did not disappoint him!

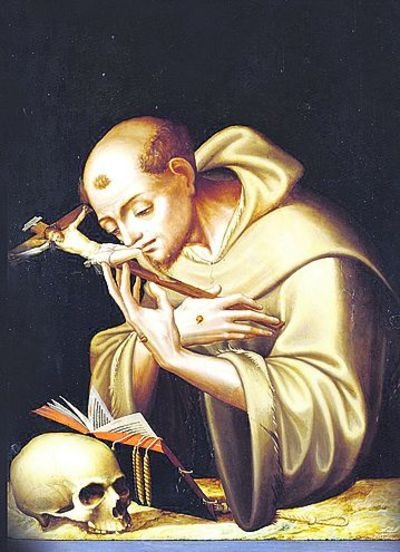

Without much hesitation, Bohdan Ivanovych took everything in bulk and was rewarded: the rarest work by Juan de Zurbarán (1620—1649), Still Life with a Chocolate Mill got in his collection. It is believed that many of the paintings by the artist’s father, Francisco, were created with his help. However, the raging plague did not spare him.

At that, every collector has mistakes. This turned out to be the acquisition of the lovely Infanta, who has been attributed as the work of Diego Velázquez for almost a hundred years. Khanenko acquired this painting in 1912 at the sale of the collection of the Consul Eduard F. Weber (at that time, the most significant private collection of old masters in Germany). The provenance of the work states that in 1891, the Portrait of the Infanta Margarita from the collection of Don Sebastian was acquired by a certain Colnaghi, who, in turn, sold the most valuable painting to Weber. For a long time the world’s big names did not agree to recognize the Kyiv Infanta.

In 2008, scholars finally attributed the painting to Juan Batista del Maso, a student of Velázquez, and dated it to 1665. But many visitors to the Museum are still striving to the hall, where the Infanta Margarita, albeit pained not by Velázquez, shimmers with her pearls from time immemorial.

Knowledge and money

At the time of the beginning of the Tereshchenko-Khanenko collection, few people promoted the investment attractiveness of art. Today, it is much talked, and in many ways, this motive becomes fundamental for collecting works of art. They collect them indiscriminately, without examination, without even having primitive knowledge. It results in an unjustified rise in prices and the emergence of artistic myths. But in collecting works of art, the main thing is not their financial viability, but love! And only when a collector acquires artifacts intuitively (but not without a foundation of his subtle taste), then he can discern the master’s handwriting even in the twilight of a candle, take the trail of a masterpiece like a hound and catch the prey with a stranglehold.A collection cannot be gathered without money, it is obvious, but at the same time one should not forget about knowledge. Khanenko’s library contained about 3 thousand books on art history, he consulted with the most famous specialists of that time. His collection is considered outstanding not so much for the number of exhibits as for their artistic value. And Bohdan Ivanovich used an encyclopedic approach to the creation of his museum. It is not for nothing that over the main staircase, after the restoration of the building in 1987—1998, a cleared inscription became visible, the first terzina of the 4th chapter of Dante Alighieri’s Divine Comedy:

Art in the city: masterpieces for Kyiv

Khanenkos moved to Kyiv from St. Petersburg in 1881. By this time, it had already become obvious that the collection did not fit into their apartment and a separate room had to be built for it; moreover, the couple considered it a crime to hide their acquisitions from the public. Some prefer to admire alone, others show off in a narrow circle of close friends, and some open museums and open doors for everyone.The couple had no children, and the Museum became the fruit of their many years of love and care. They considered having, for example, a painting by Titian or Greek marble of the fifth century and not showing these things is the same as taking over the unpublished works by Goethe, Pushkin or Shakespeare. The creations of geniuses, in essence, should not only belong to those who own them — this was the credo of Bohdan Khanenko.

She passed away in 1922 and was buried next to her husband, in the cemetery near the Vydubetsky monastery