Carpets, tapestries, metal sets, table lamps and chandeliers, children’s wooden building blocks and furniture, social photography and artistic photo collages, experiments with synthetic fiber and the invention of a metal thread: female students of the Bauhaus school for art, design and architecture worked in almost all workshops and managed to achieve a huge success in designing that was unprecedented for women of that time. Today, their works are in the main museums of modern art, and industrial enterprises still produce interior items that were designed by them. And yet, very few have heard of their names. Let’s learn about the five most prominent female graduates of the Bauhaus.

Adopted in 1919, the Weimar Constitution significantly expanded women’s rights to education and employment. They could even get an office job and vote. The Bauhaus manifesto stated that anyone could become a student at the school, regardless of their gender or age. And in the first year, the preliminary course was attended by more female than male students. Those were amazing women: daughters of wealthy parents who voluntarily agreed to a half-starved life at a student dormitory, successful and married women who left everything and started again, and even a former military nurse who’d returned from the front.

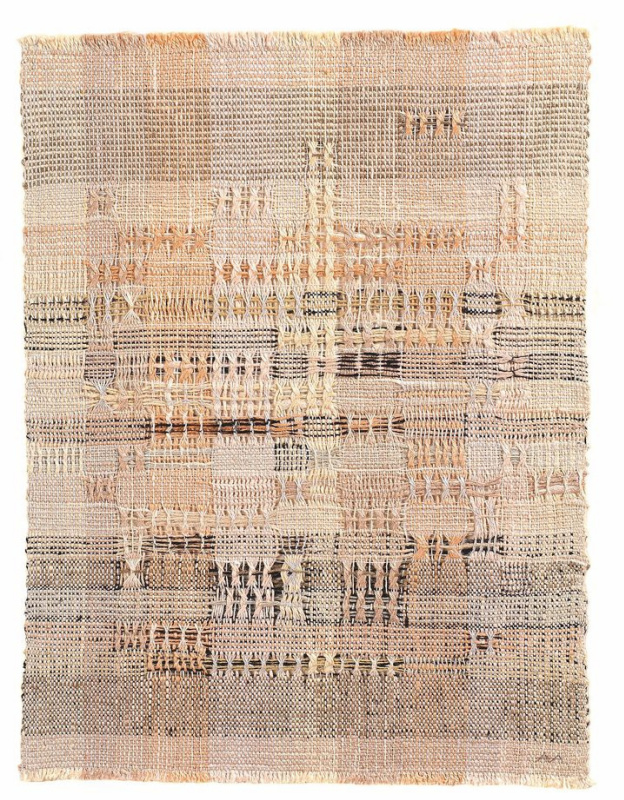

Gunta Stölzl

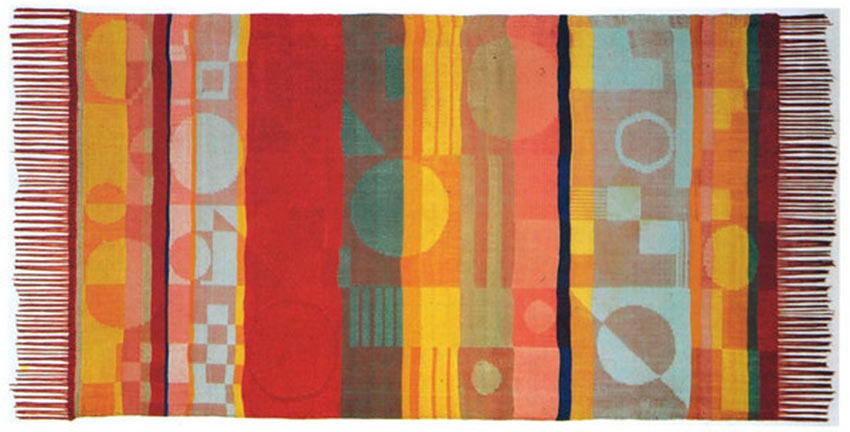

Gunta Stölzl became a student at the Bauhaus school when she was 32; at the age of 40, she was placed in charge of the weaving workshop, developed a training course and became the first woman master of the school. Before the war, she studied glass painting, decorative arts and ceramics at the Kunstgewerbeschule (School of Applied Arts) in Munich, and during World War I, worked as a Red Cross nurse. After the war, Stölzl returned to Munich to complete her studies, and it was during this time that she encountered the Bauhaus manifesto.She was among 84 women (along with 79 male students) who were admitted to the Bauhaus for the very first six-month preliminary course given by Johannes Itten. And at the end of that course, it was she who asked the school principal Walter Gropius to create a workshop in which mainly women could work. For example, a weaving workshop — the basement of the building was full of old looms, since the Bauhaus inherited the School of Arts and Crafts.

The spontaneously emerged "female" workshop needed a master of theory, and Gropius appointed architect Georg Muche to teach the weavers theoretical artistic principles. He was not that keen on weaving, so Gunta became an actual leader and generator of ideas and innovations in that field. It was she who obtained two training courses in Krefeld, the first one — to learn dyeing techniques and equip a dyeing workshop in the Bauhaus, and the second one, two years later, to master the latest weaving and fiber technologies. Then she, as a delighted admirer of abstract paintings by Paul Klee and Wassily Kandinsky, began to apply their artistic principles in her own work.

When Georg Muche (still indifferent to weaving) bought a completely unsuitable jacquard loom for the workshop, the students rebelled and demanded that he was relieved of his position. Obviously, Gunta Stölzl was voted to replace him. Under her direction, the weaving workshop became one of the most commercially successful faculties of the Bauhaus; she developed a four-year training program and issued the first ever Bauhaus weaving workshop diplomas.

Gunta Stölzl left the Bauhaus in 1931, but lived to be 96, opened several private workshops, developed innovative washable upholstery fabric for several Swiss cinemas, participated in exhibitions, received "Grand Prix" at the International exhibition in Paris, raised two daughters and lived in a small mountain cottage in Switzerland.

Gunta Stölzl left the Bauhaus in 1931, but lived to be 96, opened several private workshops, developed innovative washable upholstery fabric for several Swiss cinemas, participated in exhibitions, received "Grand Prix" at the International exhibition in Paris, raised two daughters and lived in a small mountain cottage in Switzerland.

Anni Albers

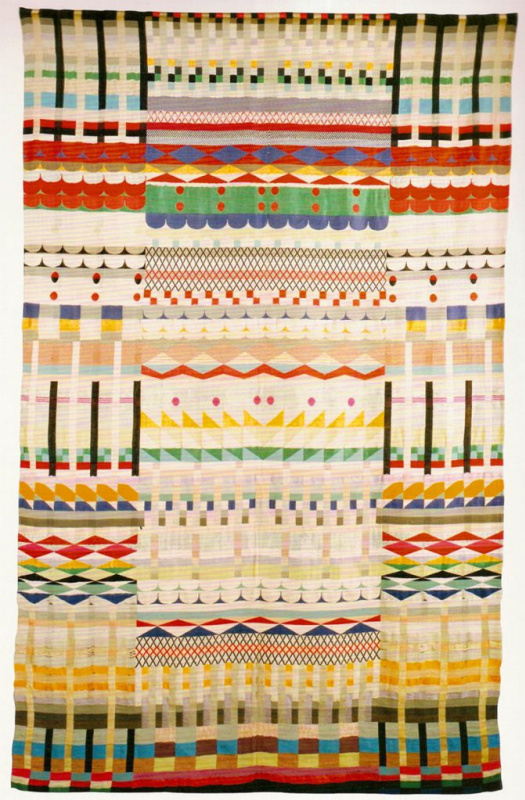

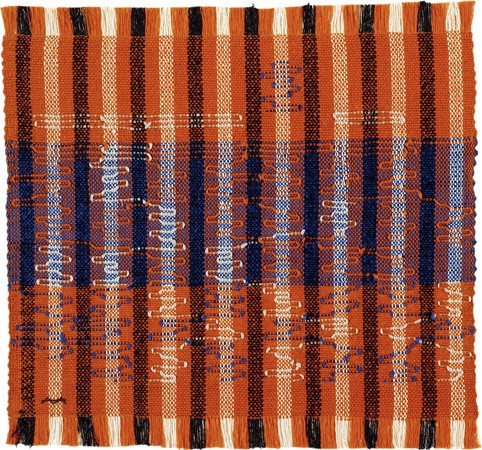

Anni Albers is perhaps the only Bauhaus female student who was much talked about during her life and who has not been forgotten after death. She was the first female textile artist to have a solo exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation was established in Connecticut, USA, thanks to funds received by Anni for the restitution of family property in Berlin. She managed to include her husband’s archives and artwork into the Foundation and save her own works, create a library and a reliable organization that is still active and provides residence and studio spaces for young artists from around the world and for educational programs. Anni Albers' works are included in the collections of the largest museums in America, Germany, Switzerland and other countries. Unlike a simple website created in the memory of Gunta Stölzl by her daughter and grandson, the Foundation’s website provides an opportunity to learn a lot about Anni Albers. Even glossy magazines write about her, tracing the influence of her textile experiments on leading fashion designers.Such popularity is in some way associated with the fact that Anni was lucky to meet a man (back at the Bauhaus), with whom she lived for more than 50 years and moved to America in 1933, when she, a Jewess, was in great danger. The rich metropolitan young lady Anni Fleishman was supposed to keep up the family tradition, get married and enjoy a comfortable idling, decorate the house and raise children, as did the women of her circle. But in 1922 she, long passionate about art, decided to go to the Bauhaus avant-garde school in Weimar. And there, she often starved and felt cold in the unheated classrooms together with other students, wore homemade skirts, exercised on the roof in the morning, swam naked and danced at parties. She considered her assignment to the weaving workshop a great advantage — while other girls were eager to work with metal or carry marble blocks, she gratefully accepted the opportunity to engage in a physically feasible craft, and at the same time attend lectures, conducted by Paul Klee, Wassily Kandinsky and Moholy-Nagy. Anni took up weaving and immediately met the artist Joseph Albers, a man became her husband in three years.

Josef was a talented student who became a young master at the end of the course — and soon, the Alberses moved from the student campus to one of the houses built for teachers. After moving to America, Anni taught, wrote theoretical design works, made jewelry from basic household items, traveled around Mexico, and got inspired by local fabrics and colorful national patterns.

Alma Siedhoff-Buscher

Actually, this woman came up with colorful building blocks, and, most likely, greatly inspired successful toy designers, including Ole Kirk Christiansen, the inventor of Lego bricks. And her "small ship-building game" remains in production today.Alma Buscher entered the Bauhaus with a certain bundle of knowledge — she studied at the training institute of the State Arts and Crafts Museum of Berlin for two years, and after attending the preliminary course run by Johannes Itten, was subsequently accepted into the Weaving Workshop. But she didn’t stay there for long. Alma was soon switched to the wood sculpture workshop — and a year later participated in the Bauhaus exhibition, organized to demonstrate the students' achievements. She also designed the interior for a children’s room at "Haus am Horn." And a year later, one of the kindergartens in Jena was fitted out with furniture she designed.

After attending Wassily Kandinsky’s lectures on color and learning the most avant-garde

and innovative techniques for working with simple figures and materials, Alma Buscher developed a small set of wooden blocks which could be constructed into the shape of a boat. Or rearranged into something else. These were toys that, on the one hand, taught kids to follow a given pattern, and on the other one, allowed for a free hand and creative experimentation.

Unfortunately, Alma Buschehr’s performed her design activities only in the Bauhaus period, because later she married the dancer Werner Siedhoff, often moved together with him, because he was actively touring the whole country, and gave birth to two children. She died in 1944 in a bombing raid on a suburb of Frankfurt am Main. She was only 45 years old.

Despite a short creative experience and a tragic death, Alma Siedhoff-Buscher determined the development of the children’s toy industry in almost the most iconic directions: in addition to wooden blocks, she also created cut-out kits and coloring books, which were immediately printed in one of the German publishing houses. And since then, nothing has really changed in furniture for children’s rooms: bright cubic transformer designs are still the best solution.

Unfortunately, Alma Buschehr’s performed her design activities only in the Bauhaus period, because later she married the dancer Werner Siedhoff, often moved together with him, because he was actively touring the whole country, and gave birth to two children. She died in 1944 in a bombing raid on a suburb of Frankfurt am Main. She was only 45 years old.

Despite a short creative experience and a tragic death, Alma Siedhoff-Buscher determined the development of the children’s toy industry in almost the most iconic directions: in addition to wooden blocks, she also created cut-out kits and coloring books, which were immediately printed in one of the German publishing houses. And since then, nothing has really changed in furniture for children’s rooms: bright cubic transformer designs are still the best solution.

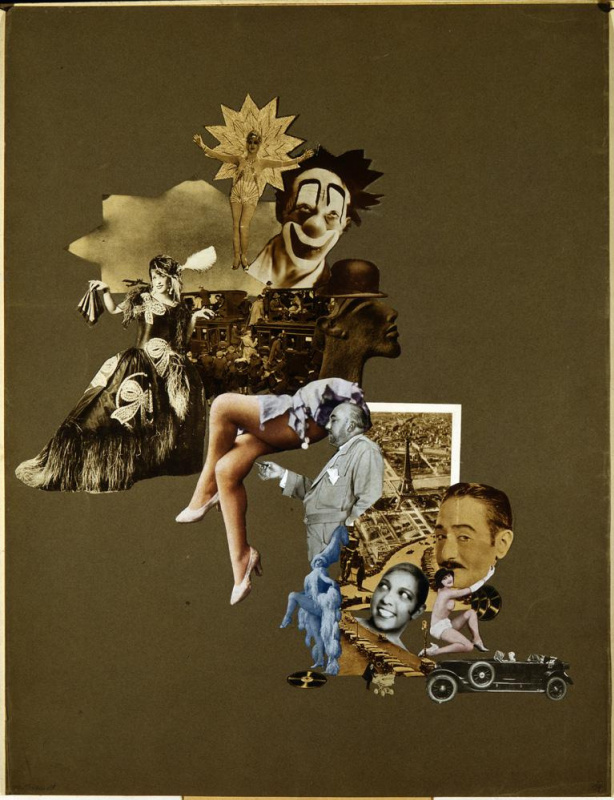

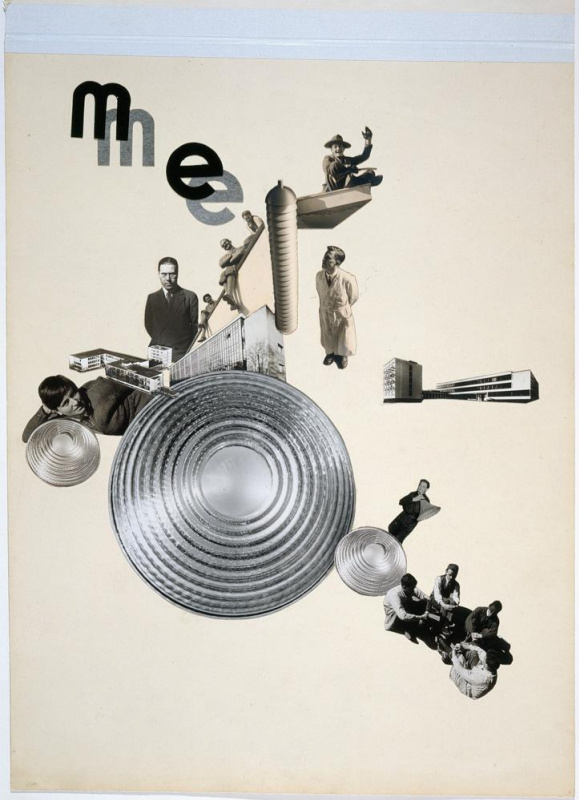

Marianne Brandt

In 2001, the International Marianne Brandt Award was established in her hometown of Chemnitz. Every three years, young designers, photographers, and artists participate in the contest with the motto "The Poetry of the Functional," displaying their designs that combine functionality and artistic character. The two-months-lasting exhibition of the best works always opens on or around Brandt’s birthday. A prize of €5,000, as well as three awards are bestowed in all three categories.Marianne Brandt was a student who broke stereotypes concerning female and male fields of activity, as well as those deeming certain crafts appropriate or inappropriate for frail girls. She joined the Bauhaus school in 1923 as a certified artist who participated in exhibitions, and attended the preliminary course which at that time was taught not by Johannes Itten but by László Moholy-Nagy. And at after that, she was sent off (like most girls) to a weaving workshop. When Moholy-Nagy headed the metal workshop, she asked him to let her study under him. And he opened a space for her — the only girl among male students.

According to the recollections of her colleagues, she was very miniature, short and fragile, so few believed that she would really succeed at heavy manual labor. But already in the first year, Marianne Brandt designed and manufactured the majority of the most iconic objects to come out of the Bauhaus — those that made the school’s unique functional style recognizable: metal tea sets. When the school relocated from Weimar to Dessau, Marianne designed an entire lighting system for it — pendant lamps made of glass and metal and table lamps. Most of her projects were brought into circulation and added significant profit to the Bauhaus, while the most significant of them are still being produced.

When Moholy-Nagy stepped down as head of the metal workshop in 1928, it was Brandt who replaced him. And when Walter Gropius resigned as director of the Bauhaus and founded a private architectural office, Brandt became his assistant. After the closure of the Bauhaus, Marianne’s track record frightened employers rather than aroused admiration — both under the Third Reich and in the German Democratic Republic, where she was not even able to receive a reward for her design of a tea set that was put into production in Italy.

When Moholy-Nagy stepped down as head of the metal workshop in 1928, it was Brandt who replaced him. And when Walter Gropius resigned as director of the Bauhaus and founded a private architectural office, Brandt became his assistant. After the closure of the Bauhaus, Marianne’s track record frightened employers rather than aroused admiration — both under the Third Reich and in the German Democratic Republic, where she was not even able to receive a reward for her design of a tea set that was put into production in Italy.

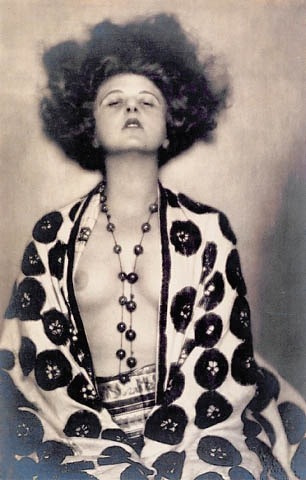

Gertrud Arndt

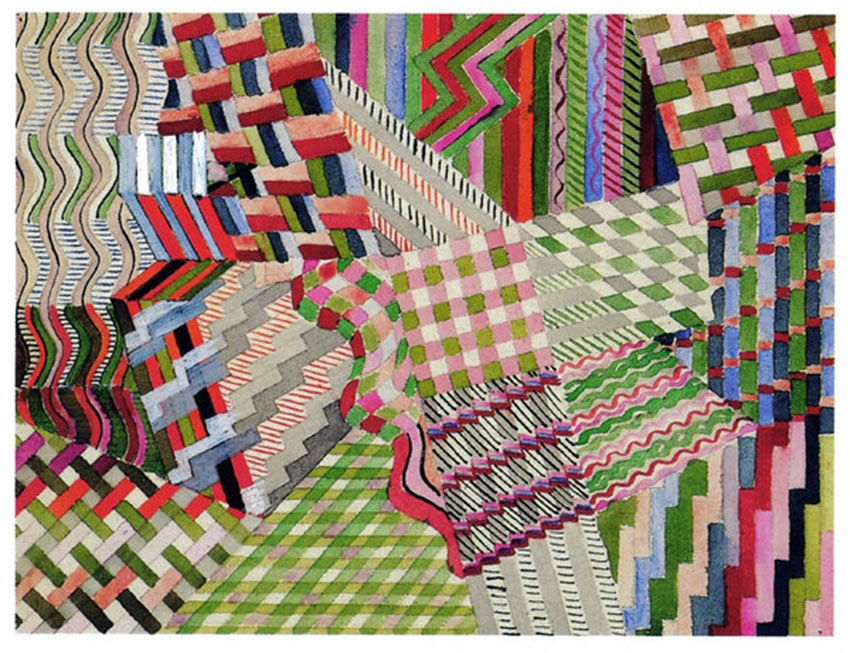

Gertrud Arndt’s life is a story of self-realization, and finding a path not thanks, but contrary to the Bauhaus methods. Walter Gropius genuinely believed that women couldn’t take up architecture, because it was quite obvious that they thought in two dimensions (and therefore were able to capture details and subtleties), while men could handle three (seeing the whole picture and not noticing the details). Strange as it may sound to us, living in the world after Zaha Hadid, this theory was very strong a hundred years ago.Gertrud Hantschk dreamed of becoming an architect and even pursued a three-year training at an architectural studio, where she picked up a camera for the first time — to capture the buildings, textures and elements that interested her. When the girl visited the first exhibition of the Bauhaus school for art, design and architecture in 1923, she decided that there had to be an architectural department there. And entered it. An architectural workshop appeared in the Bauhaus only in 1927, when the school moved to Dessau. Therefore, after the preliminary course, Gertrude had to weave tapestries and carpets and married the student Alfred Arndt.

Surprisingly, Gertrude Arndt considered the preliminary course the most significant one in the Bauhaus. Because it was taught by László Moholy-Nagy — a teacher, who was the most enthusiastic about experiments in photography. Arndt created several series of photographs in her free time — and one of them became iconic. Mask Self-Portraits are 43 pictures for which Gertrude herself posed in dresses, veils, cloaks, transparent blouses, hats and flowers. Trying on different masks of femininity, Arndt juggled with stereotyped images. She even managed to make an obvious allusion to Klimt. Modern historians of photography say that on top of everything else, she was able to use her deliberately feminine outfits to make play with a forced assignment to a weaving workshop, silk, ruching, veils, jacquards and tapestries as the only possible and suitable for a woman. After graduating, Arndt never worked in her specialty, focusing on self-education and development in the chosen field. She took photos of the buildings, designed by her husband, and lived to be 97.

Photo sources: www.moma.org, www.metmuseum.org, www. bauhaus100.com, www.icp.org, www.bauhaus.de, albersfoundation.org, wearenotamuse.tumblr.com.