Marc Chagall arrived in New York in June 1941 with a solid reputation among the art world, but with rather little luggage. His paintings followed from Spain separately, at least he thought so. They played a secondary role in the scam that allowed the Jewish artist to flee from increasingly captured by the Nazis Europe.

Alfred Barr, then director of the Museum of Modern Art in New York came up with the trick. He invited Chagall to organize a solo exhibition so that he could get a visa to the United States as soon as possible. Barr was supported by Jewish-American organizations and collectors who paid the fare. The artist and his wife Bella seized the opportunity and left France in great haste. They took what they could, but were forced to leave their two dearest values.

One of them was Ida, their only child, who could not get a visa at Barr’s invitation. The other was the main paintings of the artist.

One of them was Ida, their only child, who could not get a visa at Barr’s invitation. The other was the main paintings of the artist.

Marc Chagall and his daughter Ida in 1945. Source: artsy.net

Before leaving Europe, Chagall attempted to send his colourful canvases of cows, violinists and Russian peasants to the United States. "The artist’s main asset was his paintings," explains Susan Tumarkin Goodman, curator emeritus of the Jewish Museum in New York. In 2013 they held the Chagall. Love, War and Exile exhibition. However, the artist couldn’t arrange a safe journey across the Atlantic for his 25-year-old daughter Ida and her husband Michel Gordey.

"Everything happened too quickly to make any more plans," says Galya Diment, professor of Russian literature, who studied Chagall’s relationship with Ida and the chaotic circumstances of the artist’s departure from France. Before that, he was briefly arrested in Marseilles by the Vichy regime loyal to Hitler. "They were definitely worried about Ida’s well-being, but they understood that Chagall, because of his fame, was in danger of being arrested again and sent to the camps," continues Diment. He was not only a Jew, the Nazis branded him as a degenerate artist.

"Everything happened too quickly to make any more plans," says Galya Diment, professor of Russian literature, who studied Chagall’s relationship with Ida and the chaotic circumstances of the artist’s departure from France. Before that, he was briefly arrested in Marseilles by the Vichy regime loyal to Hitler. "They were definitely worried about Ida’s well-being, but they understood that Chagall, because of his fame, was in danger of being arrested again and sent to the camps," continues Diment. He was not only a Jew, the Nazis branded him as a degenerate artist.

Also read

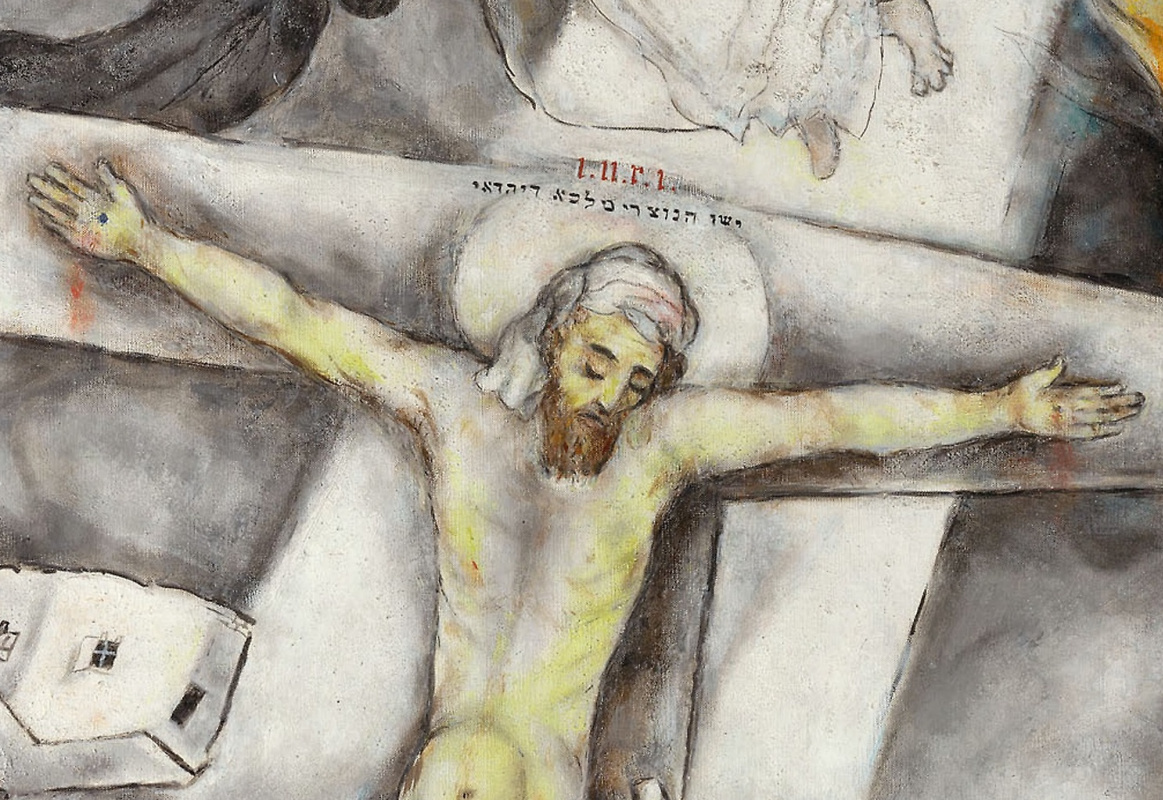

Degenerate Art

So after two years of their flight from the Third Reich, Chagall and Bella quickly left. Back in 1939, the couple left Paris, hiding further and further south as German troops approached the northern borders of France. They took the box of paintings to each new location. However, they had to send to the United States on a separate flight.

Having disembarked in America, the couple found out that Spanish customs had confiscated the precious box in Europe. Full of anxiety, Chagall wrote a letter to Ida who was stuck in the south of France, and his daughter made a heroic attempt to save her father’s work. She went herself to Spain to free the box.

Having disembarked in America, the couple found out that Spanish customs had confiscated the precious box in Europe. Full of anxiety, Chagall wrote a letter to Ida who was stuck in the south of France, and his daughter made a heroic attempt to save her father’s work. She went herself to Spain to free the box.

Blue air

1937, 116.9×86.2 cm

Things got more complicated when her husband Michel who went after his wife a few days later was arrested at the Spanish border. Ida had to make efforts for two releases at once — her father’s legacy from customs warehouses and her own spouse from prison. She brilliantly succeeded in both. "Ida skillfully and persistently played the bureaucratic harp, pulling all the necessary strings," wrote Sydney Alexander, Chagall’s biographer.

But soon another unforeseen obstacle arose: almost no ships left Europe.

By the end of the summer of 1941, there remained few such ships as the Mousinho, which brought refugees such as the Chagall couple to the United States. With a bit of luck and money from his parents (Marc and Bella could not do their bit) Michel bought two expensive tickets to board the steamer for fleeing Jews. These "passes to freedom" cost $ 600, about $ 11,000 each at current prices. The young people decided to selflessly risk their own lives and the precious works of Ida’s father.

But soon another unforeseen obstacle arose: almost no ships left Europe.

By the end of the summer of 1941, there remained few such ships as the Mousinho, which brought refugees such as the Chagall couple to the United States. With a bit of luck and money from his parents (Marc and Bella could not do their bit) Michel bought two expensive tickets to board the steamer for fleeing Jews. These "passes to freedom" cost $ 600, about $ 11,000 each at current prices. The young people decided to selflessly risk their own lives and the precious works of Ida’s father.

Taking paintings out of Europe at the start of World War II was insane, even with money. Peggy Guggenheim, an American gallerist of Jewish origin, desperately bought up works of leading artists in Paris before the German occupation. In 1941, she sent canvases from Europe, hiding them rolled up in a batch of bed linen and blankets.

Marc Chagall, Red Canopy (1939). Private collection

These conditions can be considered almost ideal compared to those in which Ida and Michel had to take out Chagall’s paintings in a box measuring 2×2×1 m. In August 1941, they got their seats on the SS Navemar steamship, which was originally intended for transporting goods and no more than fifteen people. Now, in a hurry, it was re-equipped for 1180 people and four live bulls, which were eaten during the 40-day voyage (there were no refrigerators on the ship). The conditions were terrible, but this was the only option for the refugees. Many of them died during the trip.

SS Navemar left Lisbon on 17 August. Marc Chagall and Bella anxiously monitored its movement through newspaper articles. "Today we read that Navemar is a floating concentration camp," the artist wrote in panic to Morris and Ethel Troper, the European directors of the American Jewish Joint Committee. In another message to Troper, he complained: "They are sick, temperature is 40, no medicine, no water and food. We do not sleep at night, we cannot eat, thinking that children live like animals."

Ida and Michel really lived like animals among animals. They decided to take places on the deck, in the same place where the makeshift bull stall was located, so that the moisture would not damage the paintings. We don’t know how many works Ida brought to the ship, every centimetre of which was set to save human lives.

However, both Ida and Michel and the canvases survived the journey. Chagall’s daughter’s intuitive decision to travel on deck proved to be wise, because all the luggage in the ship’s hold had rotted and was thrown away in New York.

However, both Ida and Michel and the canvases survived the journey. Chagall’s daughter’s intuitive decision to travel on deck proved to be wise, because all the luggage in the ship’s hold had rotted and was thrown away in New York.

Revolution

1937, 50×100 cm

In 1945, Ida organized another operation to rescue her father’s work from Europe. According to a legend, once in a Parisian café she sat down with an American intelligence officer Konrad Kellen and asked if he was going home. When he answered in the affirmative, she persuaded him to take many of Chagall’s paintings with him, leaving one for himself as payment. Kellen reluctantly agreed, and transported the paintings for more than a month, protecting them from all dangers. He sold his "fee" canvas in the 1950s.

The Museum of Modern Art in New York organized Chagall’s solo exhibition nevertheless, the one invented by Alfred Barr to get the artist out of Europe at the beginning of the war. It took place in 1946, and it was, say, the long-awaited return of the artist to his normal career after years of global chaos and personal disorder. The successful Jewish artist was on display in the immediate aftermath of the Holocaust, and his enchanting paintings of soaring lovers, huge roosters and brooding rabbis could hardly have survived if not for the courage and determination of his daughter Ida.

Based on Artsy materials

The Museum of Modern Art in New York organized Chagall’s solo exhibition nevertheless, the one invented by Alfred Barr to get the artist out of Europe at the beginning of the war. It took place in 1946, and it was, say, the long-awaited return of the artist to his normal career after years of global chaos and personal disorder. The successful Jewish artist was on display in the immediate aftermath of the Holocaust, and his enchanting paintings of soaring lovers, huge roosters and brooding rabbis could hardly have survived if not for the courage and determination of his daughter Ida.

Based on Artsy materials