In June 2018, the Louvre laboratory conducted a top-secret examination of the world’s most expensive piece of art, the Saviour of the World. The study

was part of preparations for a blockbuster exhibition marking the 500th anniversary of Leonardo da Vinci's death. It ran from October 2019 to February 2020. As a result, a booklet was issued in which the experts clearly stated their findings. It appeared for a very short time in the Louvre book store, after which the edition was removed from the shelves. So what did the researchers find?

"The results of historical and scientific research… allow us to confirm the attribution of Leonardo da Vinci’s work," wrote the director of the museum, Jean-Luc Martinez, in the foreword.

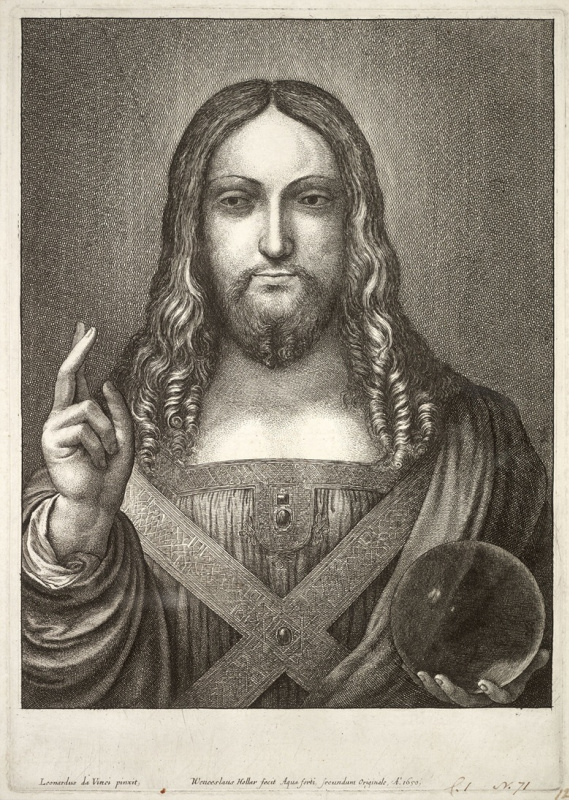

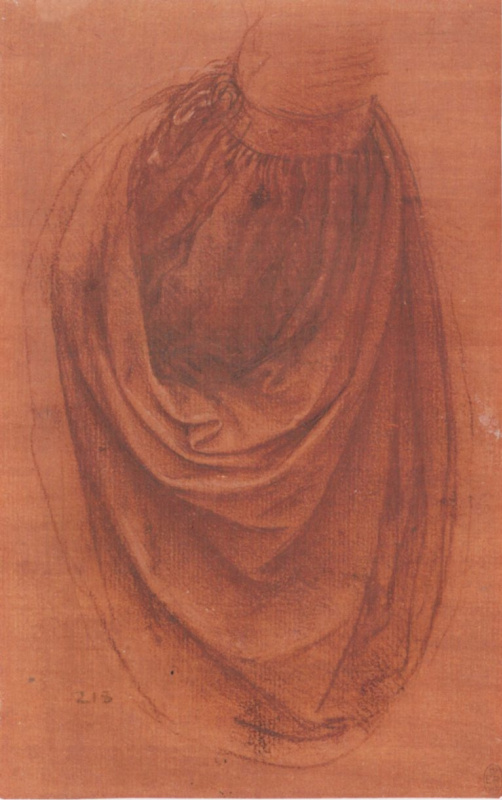

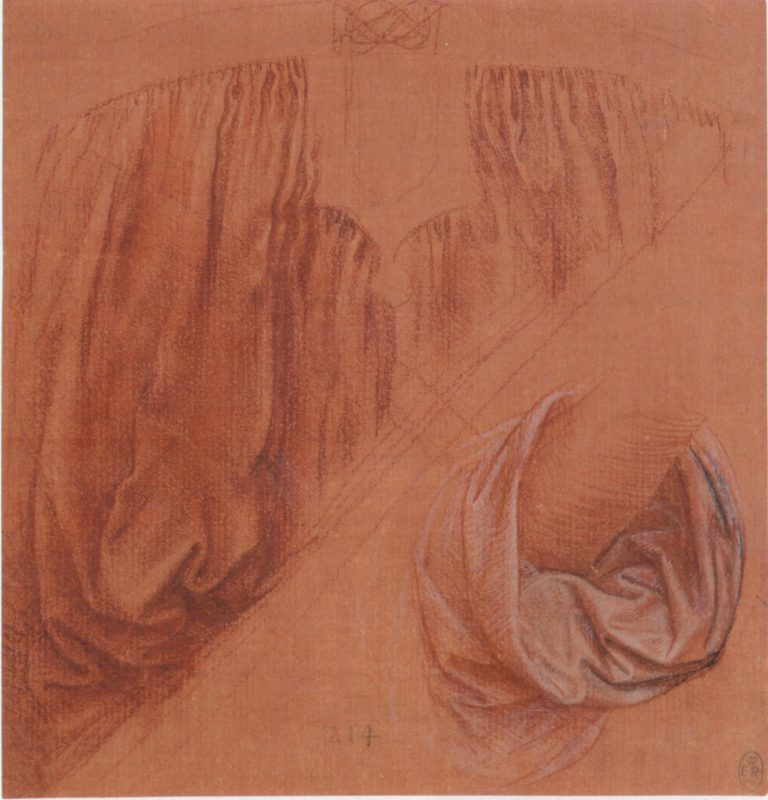

The book is illustrated with detailed X-ray and infrared images taken in the laboratory. The scholars conclude that all the elements studied at the Louvre "encourage us to give preference to the idea that the work is completely original". In his essay, the chief curator of the Louvre painting department, Vincent Delieuvin, mentioned that there is no evidence of Leonardo’s authorship in the documents of that time. At the same time, there are his preparatory drawings for The Saviour of the World in the Royal Collection in Windsor and a 17th century engraving Salvator Mundi by Wenzel Hollar signed "Leonardo painted this".

The book is illustrated with detailed X-ray and infrared images taken in the laboratory. The scholars conclude that all the elements studied at the Louvre "encourage us to give preference to the idea that the work is completely original". In his essay, the chief curator of the Louvre painting department, Vincent Delieuvin, mentioned that there is no evidence of Leonardo’s authorship in the documents of that time. At the same time, there are his preparatory drawings for The Saviour of the World in the Royal Collection in Windsor and a 17th century engraving Salvator Mundi by Wenzel Hollar signed "Leonardo painted this".

Research allows scientists to confirm, in particular, the origin of the painting from the Cook collection. Delieuvin notes its significant damage over the centuries, the fact that the wooden panel is split in two, as well as a serious loss of colour in the central part, which explains, first of all, the "ghostly" face of Christ.

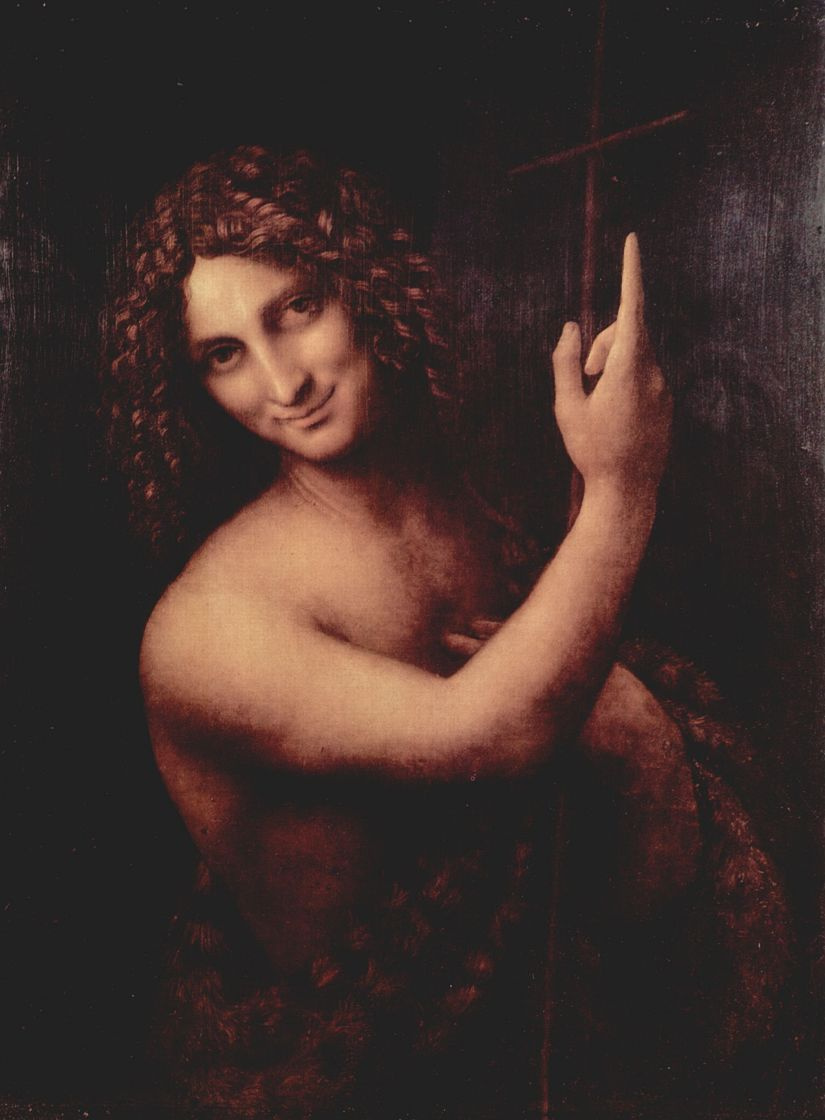

The findings of French experts largely confirm the conclusions obtained by the restorer Dianne Modestini. Additional arguments were found during research on Leonardo’s masterpieces from the Louvre collection. In particular, these are The Virgin and Child with Saint Anne, St. John the Baptist and Mona Lisa. The two latter are especially important.

The findings of French experts largely confirm the conclusions obtained by the restorer Dianne Modestini. Additional arguments were found during research on Leonardo’s masterpieces from the Louvre collection. In particular, these are The Virgin and Child with Saint Anne, St. John the Baptist and Mona Lisa. The two latter are especially important.

The Virgin and Child with Saint Anne

1510, 168×112 cm

Key takeaways from the book

• The panel is of walnut used by Leonardo and his circle, especially in Lombardy (the artist spent a significant part of his life in Milan).• There is a subtle "almost imperceptible" initial drawing (visible in infrared images) "very close to Mona Lisa and St. John the Baptist". The picture itself is strikingly different from studio copies, especially from the two most similar to it — the version of the Marquis de Ganay or the image from San Domenico Maggiore in Naples. Both of them are also painted on walnut panels and are similar in composition.

• Scientists have discovered a number of serious pentimentos (adjustments made by the artist in the process). Delieuvin mentions that the blessing hand did not seem to be part of the original composition, this is indicated by the black background behind it. The scientist also notes a change in the position of the thumb.

• Hair curls, arms, some parts of the mouth and eyes are great. They have a much more pronounced volume than the two mentioned versions. The mouth resembles that of St. John the Baptist.

• "Despite the gaps and scuffs, in the best-preserved parts one can trace a particularly virtuoso visual technique based on transparent glaze, which allows making subtle transitions from shadow to light, softening the contours (the famous ‘sfumato') and emphasizing the face relief. This technique refers to the work of Leonardo within his mature period between 1500 and 1510, such as St. John the Baptist."

• Hair curls, arms, some parts of the mouth and eyes are great. They have a much more pronounced volume than the two mentioned versions. The mouth resembles that of St. John the Baptist.

• "Despite the gaps and scuffs, in the best-preserved parts one can trace a particularly virtuoso visual technique based on transparent glaze, which allows making subtle transitions from shadow to light, softening the contours (the famous ‘sfumato') and emphasizing the face relief. This technique refers to the work of Leonardo within his mature period between 1500 and 1510, such as St. John the Baptist."

Saint John The Baptist

1513, 69×57 cm

Delieuven then analyses the provenance proposed by the National Gallery in London in 2011. The museum article formed the basis for the description at the Christie’s auction, which sold the painting as "the property of the three kings". The chief curator of the Louvre painting department called the hypothesis that the panel was commissioned by the French monarch Louis XII as "weak, if not completely false". The date of the painting creation in 1500 defined by the National Gallery is also doubtful. "Based on the information available at the moment, it cannot be argued that the artist made this composition on behalf of Louis XII. Whatever it was, it is unlikely that [he could have done it] in 1499, because the preserved archival documents indicate that Louis expressed a desire to acquire his paintings only after 1507".

Delieuven emphasizes the main things that distinguish the examined panel from other works of Leonardo’s studio, including de Ganay’s version, which was shown at the exhibition in the Louvre. It is "a very subtle underpainting, the presence of numerous pentimentos and the exceptional pictorial quality of well preserved parts."

"All these factors lead us to give preference to the idea that the work is completely original and, unfortunately, damaged due to poor storage and previous rough restorations," the expert concludes.

Delieuven emphasizes the main things that distinguish the examined panel from other works of Leonardo’s studio, including de Ganay’s version, which was shown at the exhibition in the Louvre. It is "a very subtle underpainting, the presence of numerous pentimentos and the exceptional pictorial quality of well preserved parts."

"All these factors lead us to give preference to the idea that the work is completely original and, unfortunately, damaged due to poor storage and previous rough restorations," the expert concludes.

His findings are supported by scientific evidence of Myriam Eveno and Elisabeth Ravaud of the National Centre for Research and Restoration in French Museums (C2RMF). They describe the non-invasive procedures with which they examined the panel and make the following conclusions:

"It seems to us that Leonardo really painted the picture. In this context, it is important to distinguish the original fragments from those that have been altered or repainted […] Microscopic examination revealed a very skilful execution, especially in the colouring of the skin and in the curls of the hair, as well as incredible sophistication, especially in depicting the embroidery", stated the article.

They continue: "Radiography revealed the same faint lines as in the images of St. Anne, Mona Lisa, and St. John the Baptist, characteristic of Leonardo’s work after 1500. The number of changes made during the creation of the work also speaks in favour of its originality. The first version of the peaked central "bib" is immediately comparable to the central part of the tunic in the drawing from Windsor Castle and, as far as we know, is not found anywhere else."

"It seems to us that Leonardo really painted the picture. In this context, it is important to distinguish the original fragments from those that have been altered or repainted […] Microscopic examination revealed a very skilful execution, especially in the colouring of the skin and in the curls of the hair, as well as incredible sophistication, especially in depicting the embroidery", stated the article.

They continue: "Radiography revealed the same faint lines as in the images of St. Anne, Mona Lisa, and St. John the Baptist, characteristic of Leonardo’s work after 1500. The number of changes made during the creation of the work also speaks in favour of its originality. The first version of the peaked central "bib" is immediately comparable to the central part of the tunic in the drawing from Windsor Castle and, as far as we know, is not found anywhere else."

The Saviour of the World before restoration. Source: Christie’s

"Besides, the movement of the thumb is the same as that of St. John. After scrutinizing other works from the Louvre collection, we discovered that a number of techniques found in The Saviour of the World are typical of Leonardo — the authenticity of the preparation, the use of frosted glass, and the striking use of cinnabar in hair and shadows. All the latter elements indicate that this is a late work by Leonardo, created after Saint John the Baptist in the second Milanese period."

Without a doubt, all these findings would have been presented in the Louvre catalogue if the owner of the Saviour of the World, the Saudi Crown Prince, had allowed the painting to be sent to the exhibition. The museum withdrew the book from sale and did not discuss it, because the institution is not allowed to write about works that it did not exhibit.

But why didn’t the Saviour of the World appear at the most prestigious exhibition dedicated to the 500th anniversary of the death of its creator? The authors of The Savior For Sale documentary premièred on 13 April 2021 on French TV tried to answer this question. According to two anonymous French officials, the museum did not agree to a demand from Saudi Arabia to display the panel next to the Mona Lisa as "rock-solid Leonardo". The institution allegedly considered that the artist only "had a hand" to the image, and Prince Mohammed bin Salman, who bought the panel for $ 450 million, was offended.

The Louvre remained true to its principles and did not comment on the film. However, in a strange way, copies of their booklet on The Saviour of the World got to a number of influential media outlets, such as the New York Times.

But why didn’t the Saviour of the World appear at the most prestigious exhibition dedicated to the 500th anniversary of the death of its creator? The authors of The Savior For Sale documentary premièred on 13 April 2021 on French TV tried to answer this question. According to two anonymous French officials, the museum did not agree to a demand from Saudi Arabia to display the panel next to the Mona Lisa as "rock-solid Leonardo". The institution allegedly considered that the artist only "had a hand" to the image, and Prince Mohammed bin Salman, who bought the panel for $ 450 million, was offended.

The Louvre remained true to its principles and did not comment on the film. However, in a strange way, copies of their booklet on The Saviour of the World got to a number of influential media outlets, such as the New York Times.

Mona Lisa (La Gioconda)

1500-th

, 77×53 cm

The director of the film, Antoine Vitkine, was asked why he did not take into account the conclusions set out in the publication. He replied: "The Louvre’s official line is that the book ‘does not exist'. However, the focus of my film was on the investigation of a political decision made by Macron in September 2019, so I focused on it. I cannot explain the contradiction between the dossier sent to Macron about the Louvre’s findings and the secret book sponsored by Saudi Arabia."

According to the official version, the Louvre did not want to exhibit the Saviour of the World next to the Mona Lisa, so as not to increase the crowd. Moreover, the presence of another overvalued work in the gallery would be too much of a problem for the security service.

According to the official version, the Louvre did not want to exhibit the Saviour of the World next to the Mona Lisa, so as not to increase the crowd. Moreover, the presence of another overvalued work in the gallery would be too much of a problem for the security service.

Based on materials from The Art Newspaper and artnet. News