Dadaism

, or Dada, was a nihilistic avant-garde

art movement that mainly showed itself in painting and literature. It originated in Switzerland during World War I, and existed in the years 1916 to 1922. Later, the French Dada merged with surrealism

, and the German with expressionism

. The style was a response to the atrocities of war, to the senseless killing of millions. The Dadaists viewed Reason and Logic as the root of all armed conflicts. So, instead, their fundamental values became cynicism, anti-aestheticism, rejection of standards, irrationality, and disenchantment.

Ta-da! Dada!

For a Russian ear, Dada sounds as double yes. However, this is but only one source of the term. There is a legend that the German writer Richard Huelsenbeck once slid a paper knife at random into a dictionary, and the word the knife point landed on — dada, a colloquial French term for a hobby horse — became the new art movement’s name.Another version tells us that it was a founding father of the movement, Tristan Tzara, who came across the word dada in a dictionary. In his Dada Manifesto (1918), he wrote, ‘We read in the papers that the negroes of the Kroo race call the tail of a sacred cow: DADA. A cube, and a mother, in a certain region of Italy, are called: DADA. The word for a hobby horse, a children’s nurse, a double affirmative in Russian and Romanian, is also: DADA.' Anyway, the word sounded so much like nonsense that one could have hardly thought of a better name for the whole trend.

The term might have been favoured for its being so universal. The many different meanings (if any at all) it had in different languages represented the international character of Dadaism in general.

The rare picture on the Earth

1915, 125.7×97.8 cm

Key points

1. Dadaism was the first conceptual art movement that did not focus on creating artworks pleasing to look at. Instead, it aimed to turn the bourgeois morals on their head. This gave rise to a lot of controversial questions about society, an artist’s role, and art’s purpose.2. The Dada artists so fiercely opposed any manifestation of bourgeois culture that they were not even too great admirers of themselves. ‘Dada is anti-Dada,' they cried. The art group’s being created in Zurich, in the Cabaret Voltaire, was a fact of particular significance. The place was given its name after a 18th-century satirist, the author of the celebrated Candide, a novella that lampooned the stupidity of the society of those days. Hugo Ball, a co-founder of both the cabaret and Dadaism , wrote, ‘The ideals of culture and of art as a program for a variety show, that is our kind of Candide against the times.'

3. For the artists like Jean Arp, it was crucial that some parts in their works were left up to chance, and not worked upon. This approach was contrary to all the standards of creation which demanded that every art piece be carefully precalculated and finely finished. Randomisation of the creative process was the Dadaists' form of protest against the conventional art principles, their attempt to determine the artist’s role in the act of creation.

4. The Dadaists are, besides, known for their ‘ready-mades' — easy-to-buy everyday objects, slightly modified by the artist (if at all) and presented as artworks. Ready-mades raised a lot of controversy over the ways of art, over what can be called art, and what its purpose in society is.

Bicycle wheel

1913, 64.8×64.8 cm

But for the war

In the years of World War 1, Switzerland remained neutral. It became a sort of island of free people, among them artists from all over Europe, mostly from France and Germany. One of these refugees, the German poet and playwright Hugo Ball, opened in Zurich a nightclub that would become the cradle of the Dada — the Cabaret Voltaire.Poets and artists, who landed in safe Switzerland in the middle of the war, should have felt relieved after their lucky escape. Instead, they felt powerless and furious at what society of those days was like and how it reacted to all that was happening. So, they decided to protest by what means were available, and turned art into anti-art. Indeed, for society, it would be all the same, they thought. Thus, writers and poets began seasoning their texts with profuse obscenities and off-colour jokes. Artists took to visual puns and started using everyday objects in their works.

Одной из самых возмутительных подобных работ стала "картина" Марселя Дюшана под названием "L.H.O.O.Q". Художник взял открытку с изображением "Моны Лизы", пририсовал ей усы и козлиную бородку и подписал бессмысленной на первый взгляд аббревиатурой, за которой прячется скабрезная фраза на французском.

A piece most notorious — so great was the public indignation it aroused — was Marcel Duchamp's ‘picture' titled L. H. O. O. Q. In fact, it was a postcard of Mona Lisa, with a moustache and a goatee the artist drew to her face. The abbreviation he titled the picture with may seem a jumble of letters, but, actually, it is a veiled hint at a bawdy French phrase.

Hugo Ball said, ‘Art, for us, is not an end in itself, but an opportunity for true perception and criticism of the times in which we live.' His Cabaret Voltaire was the meeting place for the first true Dadaists — the poet Tristan Tzara, the performer and poetess Emmy Hennings, the painter Jean Arp, the visual artist and architect Marcel Janco, the writer Richard Huelsenbeck, the artist Sophie Taeuber, the painter Hans Richter and many others. They discussed the ways of art in wartime, polished the ideology of their movement, and at times, gave performances on the club’s small stage.

It is important to realise that Dada was something more than a mere pretentious pose, and the Dadaists were by no means incompetent bunglers. For them, the atrocity of war was a matter of such depression and despair that they decided to make it the matter of art in a form that could be as appalling for the public. None of the Dada art objects that have survived can be called aesthetically pleasing — actually, they were supposed to be totally anti-aesthetic. As a rule, artists preferred collage pictures, and sculptors used ‘ready-mades' — ready-made objects. Art critics find quite a reasonable explanation for this. In their opinion, the collage technique is something messy and even anarchistic: scraps of out-of-date illustrations, fragments of texts are randomly arranged to form puzzling combinations. It is even simpler with sculptors: as artistic objects, the Dadaists would use things that were not only impossible to be viewed as art pieces, but were hardly ever viewed at all — rusty bicycle wheels, broken bottles, crushed tins, dated furniture with cracked planks, rags, and binned household articles.

The fruit of years of experience

1919, 38×45.7 cm

Short history

Quite soon, Dada spread over Europe and even (largely due to Marcel Duchamp) reached America. The Dadaists issued a periodical to disseminate their anti-war and anti-art ideas. In 1918, as the war was over, a lot of Dadaist followers left Switzerland and returned to their mother-countries, but Dada kept on.In Berlin, Richard Huelsenbeck founded the Dada Club. Its geographic location made most of the art of its members politically charged. They protested against the Weimar Republic, created satirical pictures and collages, and drew political cartoons. In 1919, Kurt Schwitters, who had previously sided with the Berlin Group, set up his own group in Hannover — and was its one and only member. Another influential association of German Dadaists was in Cologne. Its leaders were Max Ernst and Johannes Theodor Baargeld.

The key protagonists of French Dada, André Breton, Louis Aragon, Paul Éluard, and Francis Picabia, were later joined by Tristan Tzara and Jean Arp. However, Picabia soon fell out with the French Dadaists. As he was leaving their circle, he accused them of having turned the movement into something Dada had always opposed — something mediocre, insipid, and commonplace.

In the years of World War I, New York, like Zurich, became a place of refuge for artists. There, Picabia and Duchamp arrived in 1915, and from there, they both would often travel to Europe and back again. It was the period when Duchamp presented his first ready-mades to the public. Picabia in New York (as well as in other cities) edited his Dada periodical 391.

The history of Dada was only six years long. Indeed, the movement was not destined to last. It is safe to say that from the very beginning, Dada was hardwired to self-destruct. The Dada artists never strove to create anything that could make them remembered for centuries. Dada just decomposed to fertilise other styles. Apart from the few Dada pieces in museums throughout the world, the only thing reminding of them is the glorious Cabaret Voltaire in Zurich, now a museum.

Dada: a fact sheet

Artists whose works were created within the movement:

Marcel Duchamp, Francis Picabia, Max Ernst, Kurt Schwitters, Jean Arp, Paul Éluard, Man Ray.Significant works

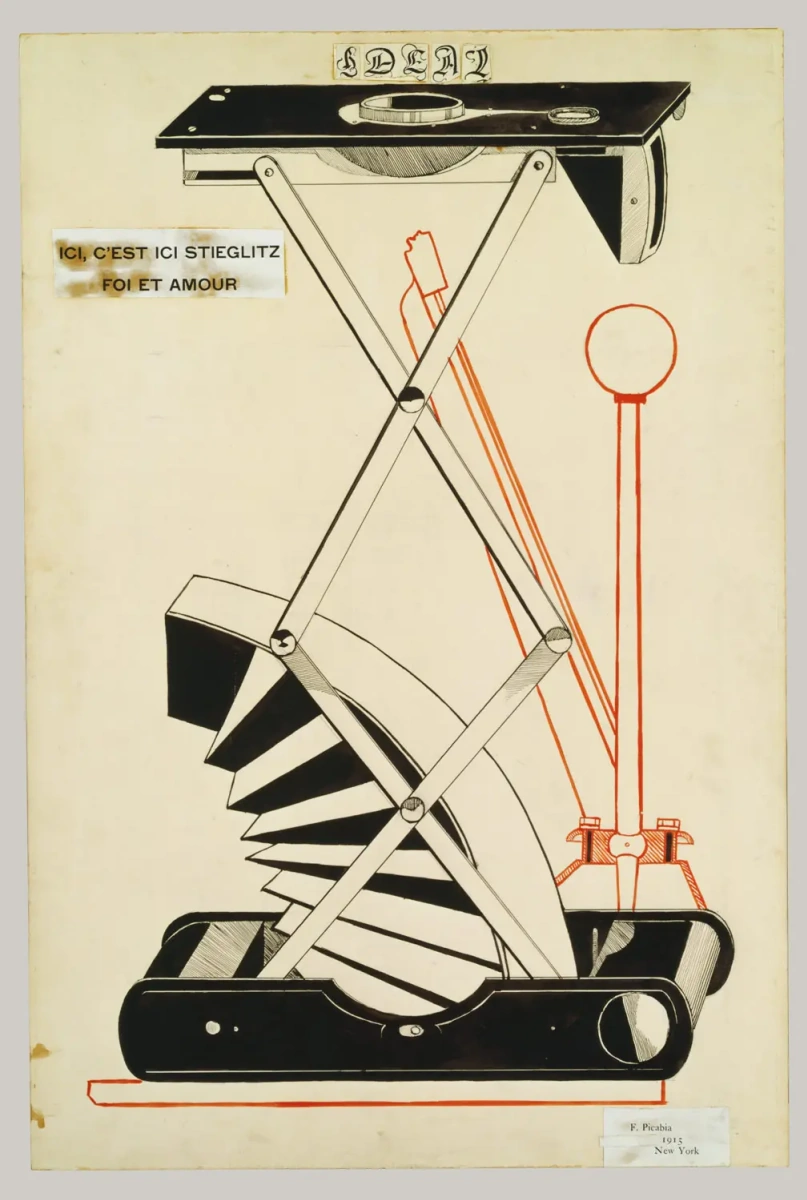

Here is Stiglitz

1915, 75.9×50.8 cm

Ici, c’est ici Stieglitz, foi et amour

Francis Picabia

1915

Picabia was a French artist who supported a number of the Dada ideas and even put forward a number of his own. He enjoyed quarrelling with tradition, and never stopped inventing new techniques and ways in art throughout his forty-five years of creation. At the start of his career, he worked side by side with Alfred Stieglitz, who put on Picabia’s first solo exhibition in New York. In 1915, though, the artist portrayed him in so mechanistic a manner that the work looks obviously critical of Stieglitz. Picabia showed him as a combination of an old broken photographic camera, a gear-box in the neutral speed position, and a brake lever. These details, along with the black-letter word IDEAL, are symbolic of Stieglitz’s values, as old-fashioned and outworn as Stieglitz himself. The ‘portrait' of the celebrated photographer was one of Picabia’s series of ‘mechanical drawings,' though the artist was never too crazy about progress.

Francis Picabia

1915

Picabia was a French artist who supported a number of the Dada ideas and even put forward a number of his own. He enjoyed quarrelling with tradition, and never stopped inventing new techniques and ways in art throughout his forty-five years of creation. At the start of his career, he worked side by side with Alfred Stieglitz, who put on Picabia’s first solo exhibition in New York. In 1915, though, the artist portrayed him in so mechanistic a manner that the work looks obviously critical of Stieglitz. Picabia showed him as a combination of an old broken photographic camera, a gear-box in the neutral speed position, and a brake lever. These details, along with the black-letter word IDEAL, are symbolic of Stieglitz’s values, as old-fashioned and outworn as Stieglitz himself. The ‘portrait' of the celebrated photographer was one of Picabia’s series of ‘mechanical drawings,' though the artist was never too crazy about progress.

Fountain

1917, 30.5×38.1 cm

Fountain

Marcel Duchamp

1917

Of all artists, Marcel Duchamp was the first to use ready-mades in his work. And the first object he chose for a ready-made was defying and provocative not only for critics and the public, but for the artist’s colleagues, too. The few modifications to it by Duchamp consisted in tipping the urinal back and signing it with a pseudonym. By removing the object from its traditional environment and transplanting it into the artistic medium, Duchamp questioned the very definition of art and the artist’s role in creating artworks. The hard-line impudence of the piece made it iconic for the Dadaists, who appreciated the highest possible disrespect for the tradition. Fountain had a drastic effect on the 20th century artists, such as Jeff Koons, Robert Rauschenberg, and Damien Hirst.

Marcel Duchamp

1917

Of all artists, Marcel Duchamp was the first to use ready-mades in his work. And the first object he chose for a ready-made was defying and provocative not only for critics and the public, but for the artist’s colleagues, too. The few modifications to it by Duchamp consisted in tipping the urinal back and signing it with a pseudonym. By removing the object from its traditional environment and transplanting it into the artistic medium, Duchamp questioned the very definition of art and the artist’s role in creating artworks. The hard-line impudence of the piece made it iconic for the Dadaists, who appreciated the highest possible disrespect for the tradition. Fountain had a drastic effect on the 20th century artists, such as Jeff Koons, Robert Rauschenberg, and Damien Hirst.

Untitled (Squares arranged according to the laws of the case)

1917, 33.2×25.9 cm

Untitled (Collage

with Squares Arranged according to the Laws of Chance)

Jean Arp

1917

This work was part of Jean Arp’s series of collages made by the leave-it-to-chance method. The artist dropped square-shaped paper cut-outs onto a large sheet of paper, then pasted them exactly where they landed. The result was as predictable as the I-Ching three-coin divination. Most probably, the technique appeared because Arp had lost faith in the traditional ways of creating geometric patterns. Arp’s collages visualised some key principles of Dada as ‘anti-art' — to leave things to chance, and defy the traditional ways of creating art objects.

Jean Arp

1917

This work was part of Jean Arp’s series of collages made by the leave-it-to-chance method. The artist dropped square-shaped paper cut-outs onto a large sheet of paper, then pasted them exactly where they landed. The result was as predictable as the I-Ching three-coin divination. Most probably, the technique appeared because Arp had lost faith in the traditional ways of creating geometric patterns. Arp’s collages visualised some key principles of Dada as ‘anti-art' — to leave things to chance, and defy the traditional ways of creating art objects.

The spirit of our time

1920, 32.5×21 cm

The Spirit of Our Time

Raoul Hausmann

1920

This assemblage was to reflect Raoul Hausmann’s frustration at the German government and its failure to change the country for the better. This is an ironic effigy of Hausmann’s belief that the ordinary citizen ‘has no more capabilities than those whose chance is glued on the outside of his skull: his brain remains empty.' To construct this piece, Hausmann used a hairdresser’s wig-making dummy, as a symbol of a typical blockhead who can only experience what can be mechanically measured. To this end, there are various tools attached to his head: a ruler, a tape measure, a pocket watch mechanism, a typewriter fragment, some brass camera handles, a holed collapsible cup, and an old wallet.

Raoul Hausmann

1920

This assemblage was to reflect Raoul Hausmann’s frustration at the German government and its failure to change the country for the better. This is an ironic effigy of Hausmann’s belief that the ordinary citizen ‘has no more capabilities than those whose chance is glued on the outside of his skull: his brain remains empty.' To construct this piece, Hausmann used a hairdresser’s wig-making dummy, as a symbol of a typical blockhead who can only experience what can be mechanically measured. To this end, there are various tools attached to his head: a ruler, a tape measure, a pocket watch mechanism, a typewriter fragment, some brass camera handles, a holed collapsible cup, and an old wallet.

Chinese nightingale

1920, 12.2×8.8 cm

The Chinese Nightingale

Max Ernst

1920

In 1919—1920, Max Ernst created a series of collages using photomontage. They featured chimerical creatures composed of fragments of military hardware, human limbs, and various accessories ‘stuck' together. The fearsome fragments of weapons he combined with softer elements and titled the works with lyrical names. No doubt these pieces were of special importance for Ernst, who had been injured during the war when his gun kicked. In The Chinese Nightingale, the artist used an English bomb as the body of a strange creature and complemented it with the arms and the fan of an oriental dancer. An eye is placed above the brace of the bomb, thus making it similar to an odd-looking bird.

Max Ernst

1920

In 1919—1920, Max Ernst created a series of collages using photomontage. They featured chimerical creatures composed of fragments of military hardware, human limbs, and various accessories ‘stuck' together. The fearsome fragments of weapons he combined with softer elements and titled the works with lyrical names. No doubt these pieces were of special importance for Ernst, who had been injured during the war when his gun kicked. In The Chinese Nightingale, the artist used an English bomb as the body of a strange creature and complemented it with the arms and the fan of an oriental dancer. An eye is placed above the brace of the bomb, thus making it similar to an odd-looking bird.

Rayograph

1922, 22.2×17.1 cm

Rayograph

Man Ray

1922

Most of his artistic life the American photographer Man Ray spent in Paris. In the 1920s, he started his photoexperiments he called ‘rayographs.' He would put different objects onto photographic paper, and then exposed it to light. The shadow-like silhouettes left on the paper were quite different from any other traditional representations of the objects. The first of these photos was typically Dadaistic, as it was obtained by sheer chance. While other Dada artists were exploring the boundaries of the possible in painting and sculpture, Man Ray was doing the same in photography. With him, it became something more than mirrored reality.

Man Ray

1922

Most of his artistic life the American photographer Man Ray spent in Paris. In the 1920s, he started his photoexperiments he called ‘rayographs.' He would put different objects onto photographic paper, and then exposed it to light. The shadow-like silhouettes left on the paper were quite different from any other traditional representations of the objects. The first of these photos was typically Dadaistic, as it was obtained by sheer chance. While other Dada artists were exploring the boundaries of the possible in painting and sculpture, Man Ray was doing the same in photography. With him, it became something more than mirrored reality.

You are an expert if you:

— know that Dada was originally a protest against not only the artistic tradition, but the social system as well;— can find the difference between the Dadaists' randomly positioned squares and the Suprematists' well-calculated geometric compositions;

— are aware that any object can be turned into an art piece.

You are incompetent if you:

— believe that the Dadaists produced collages and ready-mades only because they were incapable of painting anything worthwhile;— believe that Dada was nothing more, but provocation intended to tease the public.