When it comes to Cubism, the first artist that comes to mind is Pablo Picasso. Most online articles devoted to this revolutionary art movement mention (if at all) Georges Braque as one of the founders and pioneers of Cubism. Still, there is not much information on the details of his contribution to this process, and the way he and Picasso influenced each other’s work. Let’s try to figure out why this happened, and what relationship the reserved Frenchman and the explosive Spaniard had.

In spring of 1907, Georges Braque visited the studio of Pablo Picasso to view the artist’s notorious Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (The Young Ladies of Avignon). The Fauve Braque himself was a member of the rebellious art movement: a couple of years before, "the wild beasts" caused quite a stir in Paris. But what he saw in Picasso’s studio was something brand new. The frank, deliberate, blatant "irregularity" of the The Young Ladies of Avignon, simplified forms, broken figures and distorted proportions stunned Braque so much that he decided to make friends with this strange Spaniard at all costs. Yet, a lot of time passed between the beginning of their friendship and the start of the collaborative work. And over the long months in the works of Picasso and Braque there gradually crystallized something which later formed the basis of a style that completely changed the art world.

This union was unique, with no analogues in art history. A union of two personalities, two minds, two creative energies.

In the years that followed, Picasso and Braque were essentially inseparable. They forged a relationship that was part intimate friendship, part rivalry; they were each other’s teachers and apprentices. The two artists worked so closely together that they themselves sometimes couldn’t tell their works apart. They were scrutinizing each other’s work while challenging, motivating, and encouraging each other. Later, Picasso recalled, "Almost every evening, either I went to Braque’s studio or Braque came to mine. Each of us had to see what the other had done during the day." Braque was more poetic, expressing himself: "We were like mountain-climbers roped together."

William Rubin, former director of the Department of Painting and Sculpture at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York, best summed up Picasso and Braque’s relationship, "The collaboration between Picasso and Braque is unique in the history of art for its intensity, duration, and generative impact. No other modern style was the simultaneous invention of two artists in dialogue with each other. In the years of their association, Picasso and Braque not only produced a number of exceptionally great works, they created a visual language that could and would be used by artists with widely divergent aesthetic, literary, and political concerns. Both artists were at their best when they were closest to one another. Cubism

as we know it was a vision that neither artist could have realized alone."

Girl with a mandolin (Fanny Tellier)

1910, 100×74 cm

Still life with bottle and fish

1912, 61×74 cm

The main idea of Сubism was the rejection of conventional ideas about art as the imitation of reality. Stylistic way for this was paved by the experiments with the forms of Paul Cézanne, adored by Braque and Picasso, and by the artists' fascination with the "primitive" African art.

While their Cubist works are visually similar, Picasso and Braque often strove for different aesthetic effects. Picasso shifted his focus from narrative imagery to pictorial design, while Braque channeled his creativity towards his use of materials and textures and the manipulation of light and space.

Braque desired his works to maintain a sense of balance and harmony while Picasso strove to disrupt this sense of balance and harmony.

While their Cubist works are visually similar, Picasso and Braque often strove for different aesthetic effects. Picasso shifted his focus from narrative imagery to pictorial design, while Braque channeled his creativity towards his use of materials and textures and the manipulation of light and space.

Braque desired his works to maintain a sense of balance and harmony while Picasso strove to disrupt this sense of balance and harmony.

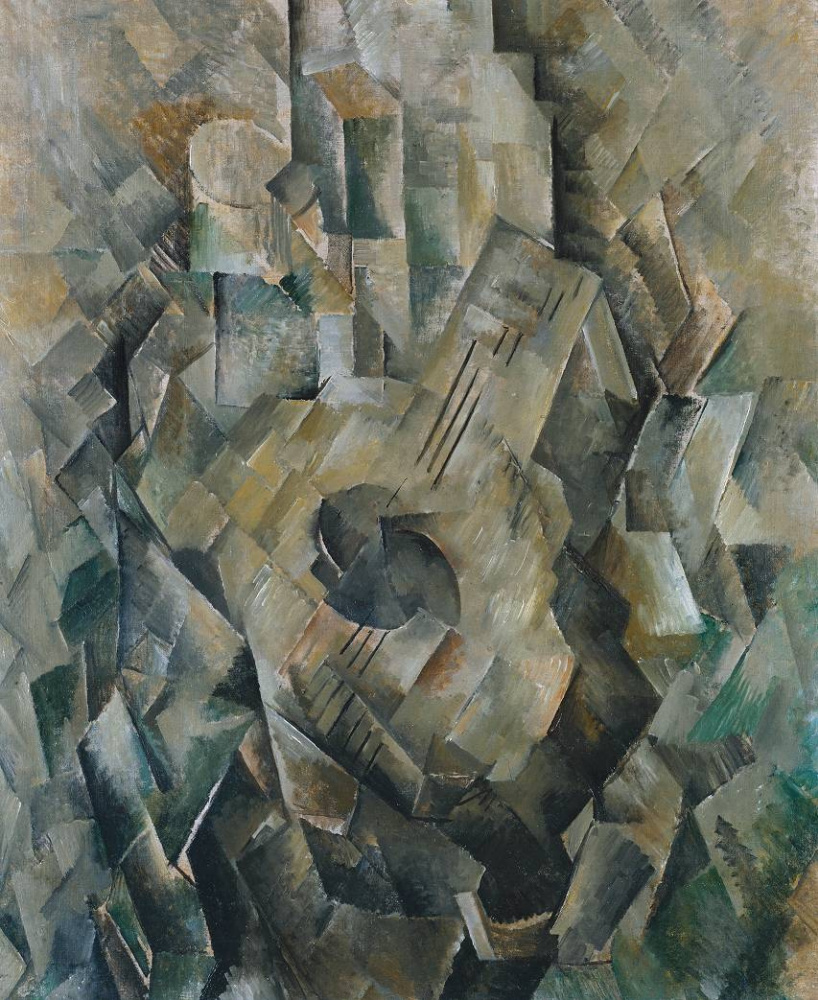

Guitar

1910, 71×55 cm

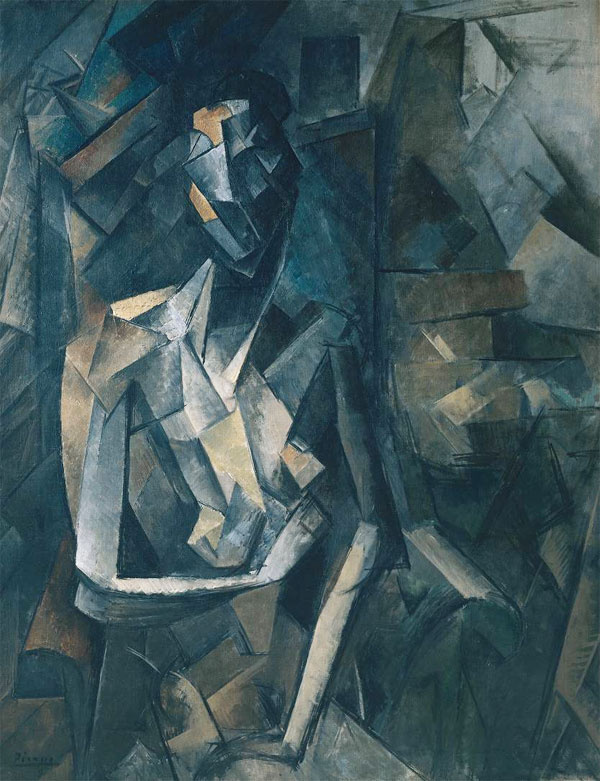

Seated Nude

1910, 92×73 cm

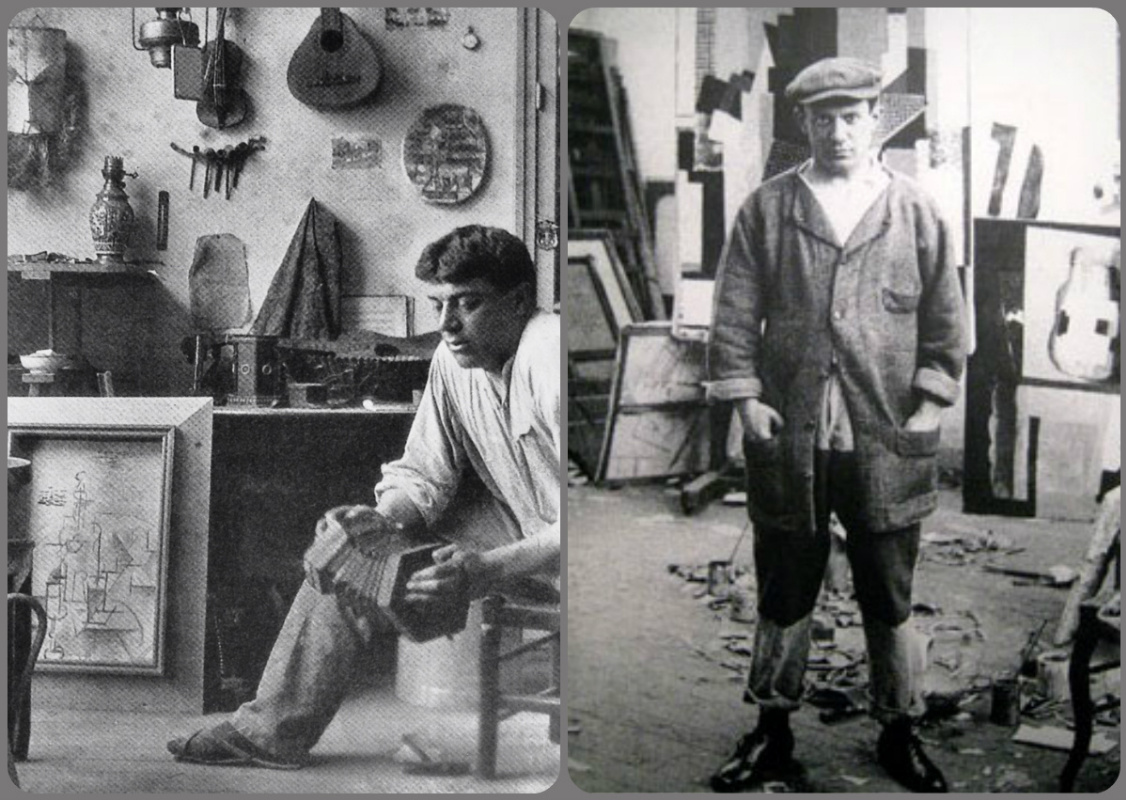

They were completely different. Picasso and Braque’s relationship epitomizes the attraction of opposites. Georges Braque’s father was a house painter and decorator who ensured that his son learned the necessary skills of his trade. Braque was a tall, reserved, systematic Frenchman whose artistic process was dictated by reason and balance. An incredibly private individual, he shunned the limelight and remained married to the same woman his entire life.

Pablo Picasso also received his first professional drawing lessons from his father, but the latter was an academic painter. Picasso was a short, egotistical, outspoken, and unpredictable Spanishman who never stuck to one woman or painting style for a prolonged period of time. Hailed as the first celebrity artist, he revelled in his public status. However, despite their vastly different backgrounds and temperaments, Picasso and Braque complemented each other.

Pablo Picasso also received his first professional drawing lessons from his father, but the latter was an academic painter. Picasso was a short, egotistical, outspoken, and unpredictable Spanishman who never stuck to one woman or painting style for a prolonged period of time. Hailed as the first celebrity artist, he revelled in his public status. However, despite their vastly different backgrounds and temperaments, Picasso and Braque complemented each other.

Georges Braque and Pablo Picasso in their studios

In the case of Pablo Picasso, his final collapse of form from the "African" period into Cubism

seemed quite logical and gradual. The same happened to colours: during his "blue" and "pink" periods, the artist created many paintings in a very limited colour palette.

As for Georges Braque, his transformation from a Fauve to a Cubist was a quantum leap. The metamorphosis was rapid and unexpected: in 1908, coming from his trip to L’Estaque, the artist brought to Paris a series of landscapes, which were absolutely new and strikingly different from his previous colourful Fauvist works (1, 2, 3). The expressive style of painting was replaced by strictness of lines and forms; the colours became restrained and subdued; in the pictures there appeared some volume and almost unspeakable "tangibility". The beauty of these paintings was undeniable, but it was beauty in a completely different sense.

As for Georges Braque, his transformation from a Fauve to a Cubist was a quantum leap. The metamorphosis was rapid and unexpected: in 1908, coming from his trip to L’Estaque, the artist brought to Paris a series of landscapes, which were absolutely new and strikingly different from his previous colourful Fauvist works (1, 2, 3). The expressive style of painting was replaced by strictness of lines and forms; the colours became restrained and subdued; in the pictures there appeared some volume and almost unspeakable "tangibility". The beauty of these paintings was undeniable, but it was beauty in a completely different sense.

Houses in l'estaque

1908, 73×60 cm

Harbor in Normandy

1909, 81×80 cm

Meanwhile, the changes marked Picasso’s work. The bulk of his work at that time were still lifes, portraits and nudes. Picasso seemed to be trying to approach a new style from different sides, tried various "breakdowns" of objects into fragments, different colour schemes, but sometimes his paintings suddenly exploded in colour, or there appeared some unexpected smoothness in them.

Three women

1908, 200×178 cm

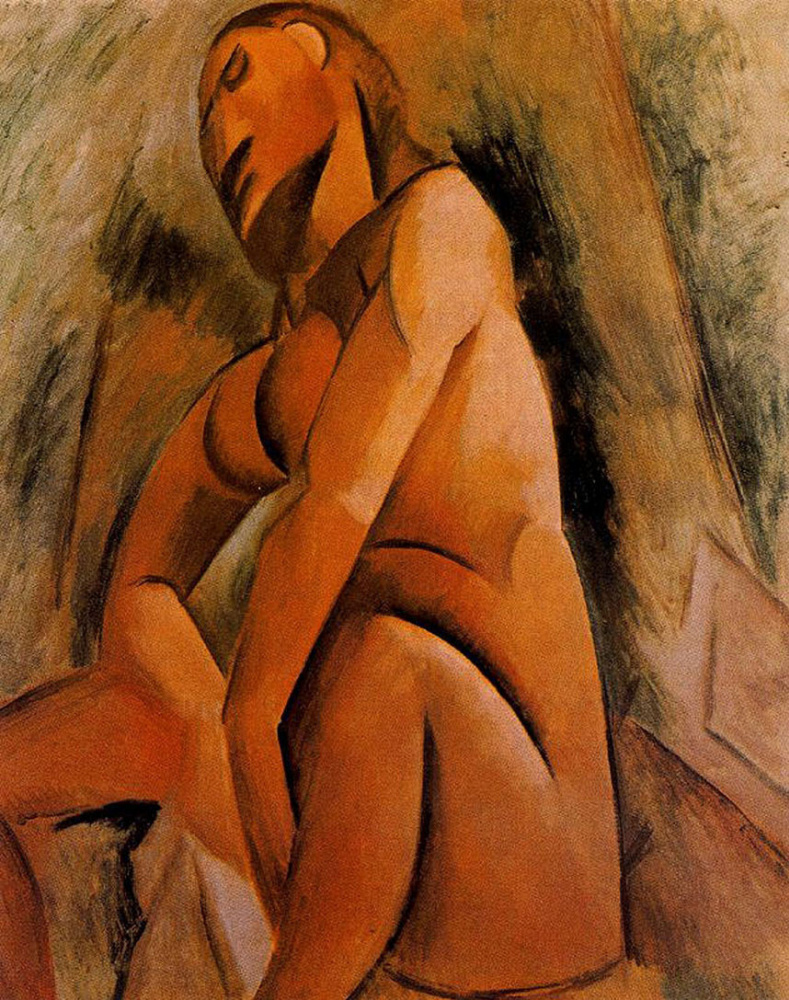

Seated Nude

1908

Soon the close cooperation between Picasso and Braque began. During 1910, the artists created incredibly complex works, the first iconic paintings relating to Analytical Cubism

.

For example, Braque’s Violin and Jug or Picasso’s Portrait of Ambroise Vollard. From a certain point of view, these paintings are very similar, but a closer look makes it apparent that at that time Braque was much more successful in playing with shadows and light, layers and perspectives. The violin in his painting is still recognizable, although it almost "dissolves" in the background, but one needs to read the title to see there the pitcher. And when you finally notice it, you are repeatedly amazed at how the artist depicted the reflection on its sides from different angles.

For example, Braque’s Violin and Jug or Picasso’s Portrait of Ambroise Vollard. From a certain point of view, these paintings are very similar, but a closer look makes it apparent that at that time Braque was much more successful in playing with shadows and light, layers and perspectives. The violin in his painting is still recognizable, although it almost "dissolves" in the background, but one needs to read the title to see there the pitcher. And when you finally notice it, you are repeatedly amazed at how the artist depicted the reflection on its sides from different angles.

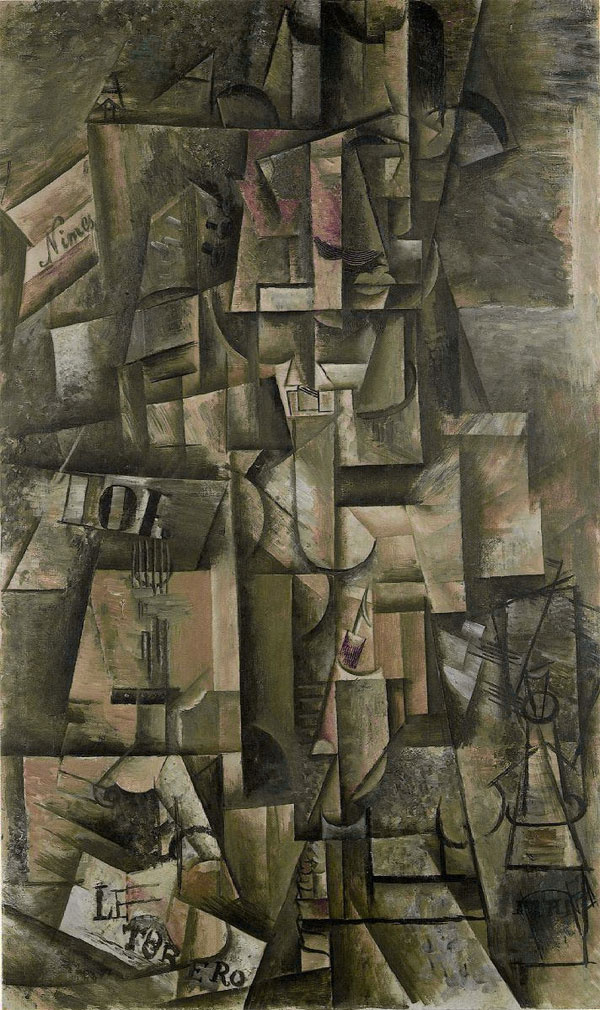

In the case of Picasso’s painting, the title is not necessary at all: it’s not difficult to distinguish Vollard’s heavy look on his angular, gloomy face. This portrait is definitely revolutionary, but it is still too dynamic and devoid of some sterility inherent in later Cubist works. In just two years, Picasso created The Aficionado (The Torero), and this painting shows what a good progress he made. He took a newspaper, a human figure, glasses on the table and broke them into fragments again, but here already appeared something what Braque called "the materialization of the new space." It becomes obvious how the styles of both artists became closer.

The Aficionado (The Torero)

1912, 134.8×81.5 cm

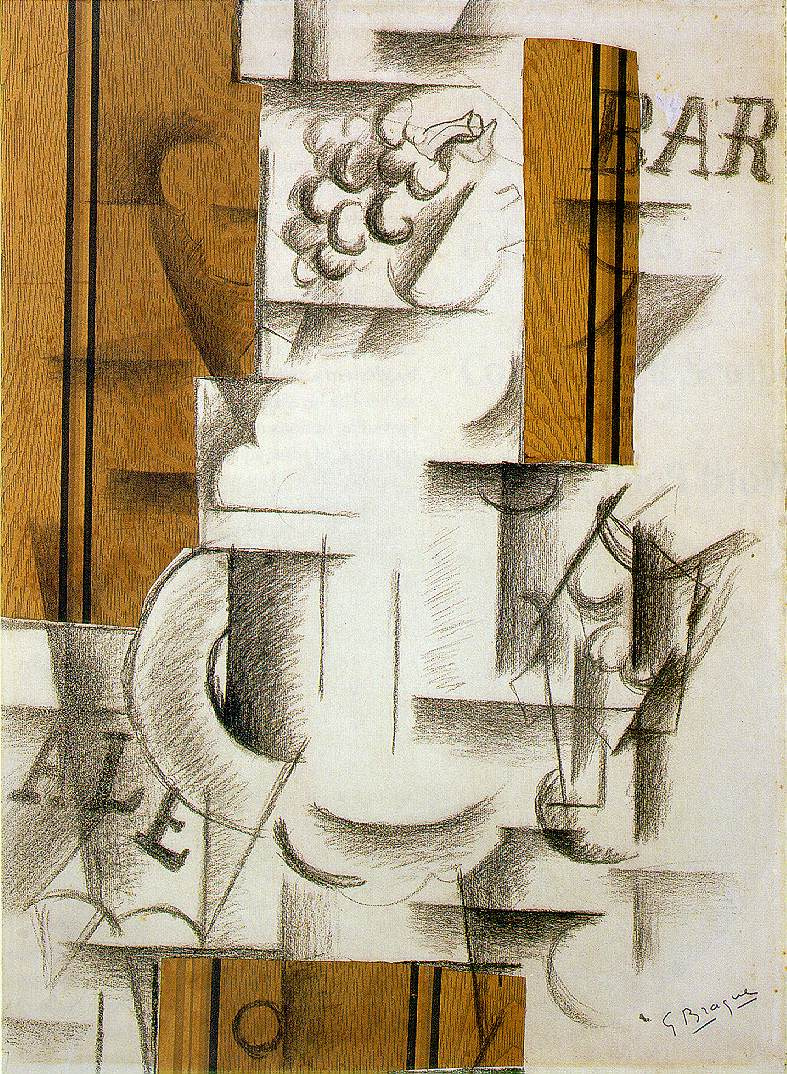

In these first years of working together, Braque and Picasso laid the foundation for Cubism

, in particular, outlined the range of common subjects. Most often these were still life with musical instruments, bottles, jugs, glasses, newspapers and playing cards, less often — human faces and figures. And extremely rarely — landscapes. At some point, both artists started pasting coloured and printed pieces of paper into their paintings, and then collage

appeared, symbolizing the era of synthetic Cubism

. Picasso is credited with inventing "collage" with his 1912 work Still Life with Chair Caning, while Braque is credited for inventing "papier collé," or pasted paper, with his work Fruit Dish and Glass.

The difference between collage and papier collé is extremely subtle — papier collé refers exclusively to the use of paper, while collage may incorporate other two-dimension (non-paper) components, suggesting that both Picasso and Braque co-created these techniques together.

The difference between collage and papier collé is extremely subtle — papier collé refers exclusively to the use of paper, while collage may incorporate other two-dimension (non-paper) components, suggesting that both Picasso and Braque co-created these techniques together.

Still Life with a Chair Caning

1912, 29×37 cm

Fruit plate and a glass

1912, 62×44 cm

And, nevertheless, the most important, and most breakthrough ideas of Cubism were often based on the technical innovations of Georges Braque. However, if he only planned a new path, it was Picasso who turned it into an asphalt high-speed highway. For example, when preparing for a collective display of artists in the MoMA in 1989, experts were able to find out that it was Braque, but not Picasso, as it was previously thought, who created the first cubist sculptures made of cardboard in 1911. But he, apparently, did not pay particular importance to them, therefore none of them reached our days. The earliest preserved similar sculpture — the cardboard "Guitar" by Picasso — was created in autumn of 1912.

Guitar

1912

Every innovative idea, every revolutionary technique, Picasso fully committed to this, and turned them into gold like King Midas. It is his commercial success and insatiable thirst for fame that explains the fact that Braque eventually found himself in his shadow.

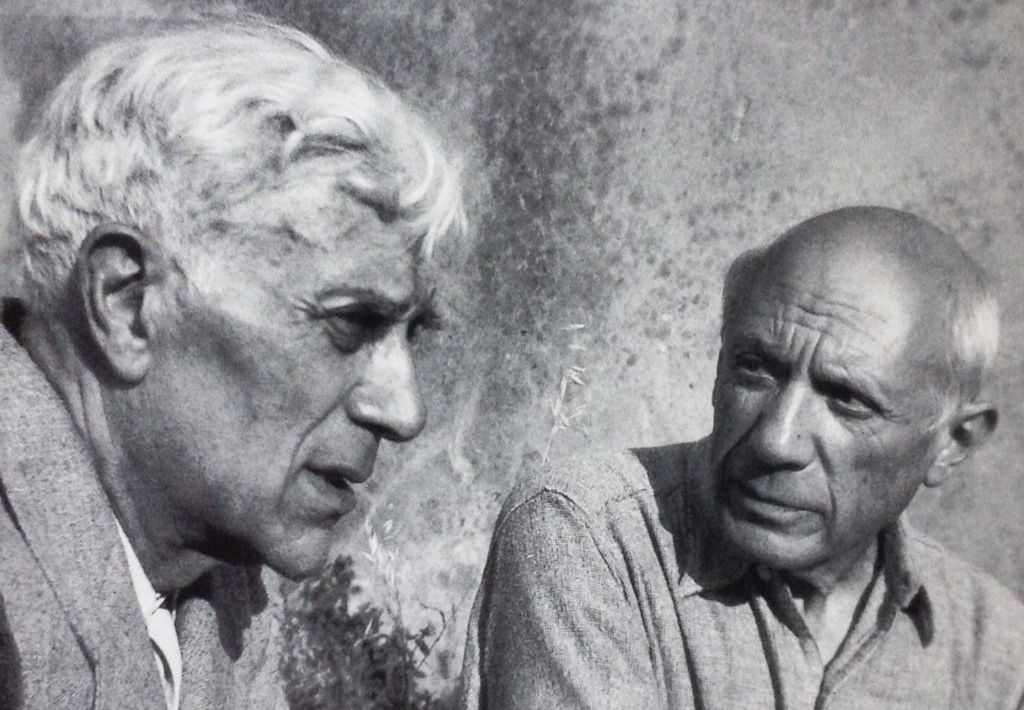

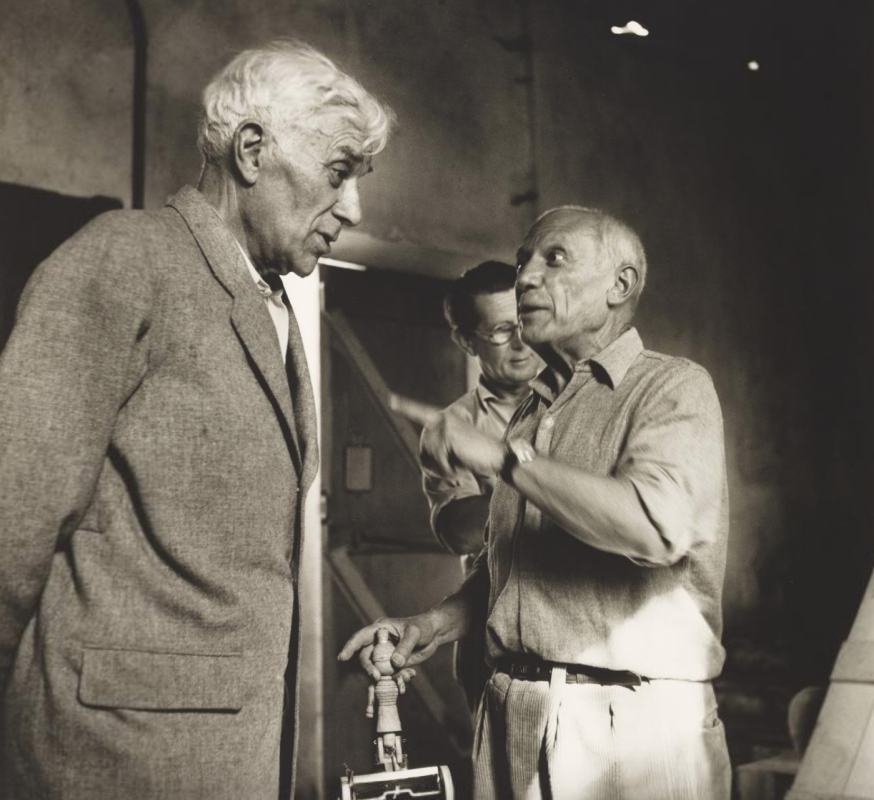

Picasso and Braque enjoyed a stint of productive artistic collaboration until the fall of 1914, when Braque enlisted in the French Army early in WWI. After the war, each of them went his own way, and although the friendship did not stop, that close connection, which made them visit each other’s studios on daily basis was irretrievably lost. Picasso and Braque occasionally made snide remarks about each other, yet spoke with respect and light sadness about the time spent together. "Picasso and I said things to one another, which will never be said again," recalled Braque. "…which no one will be able to understand."

Picasso and Braque enjoyed a stint of productive artistic collaboration until the fall of 1914, when Braque enlisted in the French Army early in WWI. After the war, each of them went his own way, and although the friendship did not stop, that close connection, which made them visit each other’s studios on daily basis was irretrievably lost. Picasso and Braque occasionally made snide remarks about each other, yet spoke with respect and light sadness about the time spent together. "Picasso and I said things to one another, which will never be said again," recalled Braque. "…which no one will be able to understand."

Georges Braque and Pablo Picasso in Vallaruris, 1954. Photo: Lee Miller

Arthive: watch us on Instagram

Cover illustration: Georges Braque and Pablo Picasso in Vallaruris, 1950.

Author: Yevgenia Sidelnikova.

Cover illustration: Georges Braque and Pablo Picasso in Vallaruris, 1950.

Author: Yevgenia Sidelnikova.