Before the storm

When Oskar Kokoschka first met Alma Mahler at the house of her stepfather, the woman was still wearing a mourning veil. It happened less than a year after the death of her first husband, the famous composer and conductor Gustav Mahler.She lived with Mahler for 10 years, gave birth to two daughters and buried one of them. She abandoned her own career as a composer, got bored and tired of being married and subject to the strict order of her husband’s life, got into several love affairs, traveled to America with Mahler, visited all the best spa resorts from sheer boredom, met Viennese celebrities. She was 33. After the death of her husband, Alma got quite a good pension, had a reputation as the most beautiful woman in Vienna, slammed the doors in the faces of several of her husband’s acquaintances, continued to enjoy freedom, assisted biologist Paul Kammerer in his experiments with mantis, but when he threatened to kill himself because of her indifference, decided to quickly put an end to her career as a biologist. By the way, Kammerer still committed suicide 15 years later, but due to the fact that his research and experiments were found to be falsified rather than because of the unhappy love.

Alma always managed to guess whether men who wanted to get closer to her possessed enough genius to tolerate their craziness, unattractiveness, Jewish roots, difference in age and other things she considered flaws. And when that degree of genius was sufficient, she was ready to tolerate a lot.

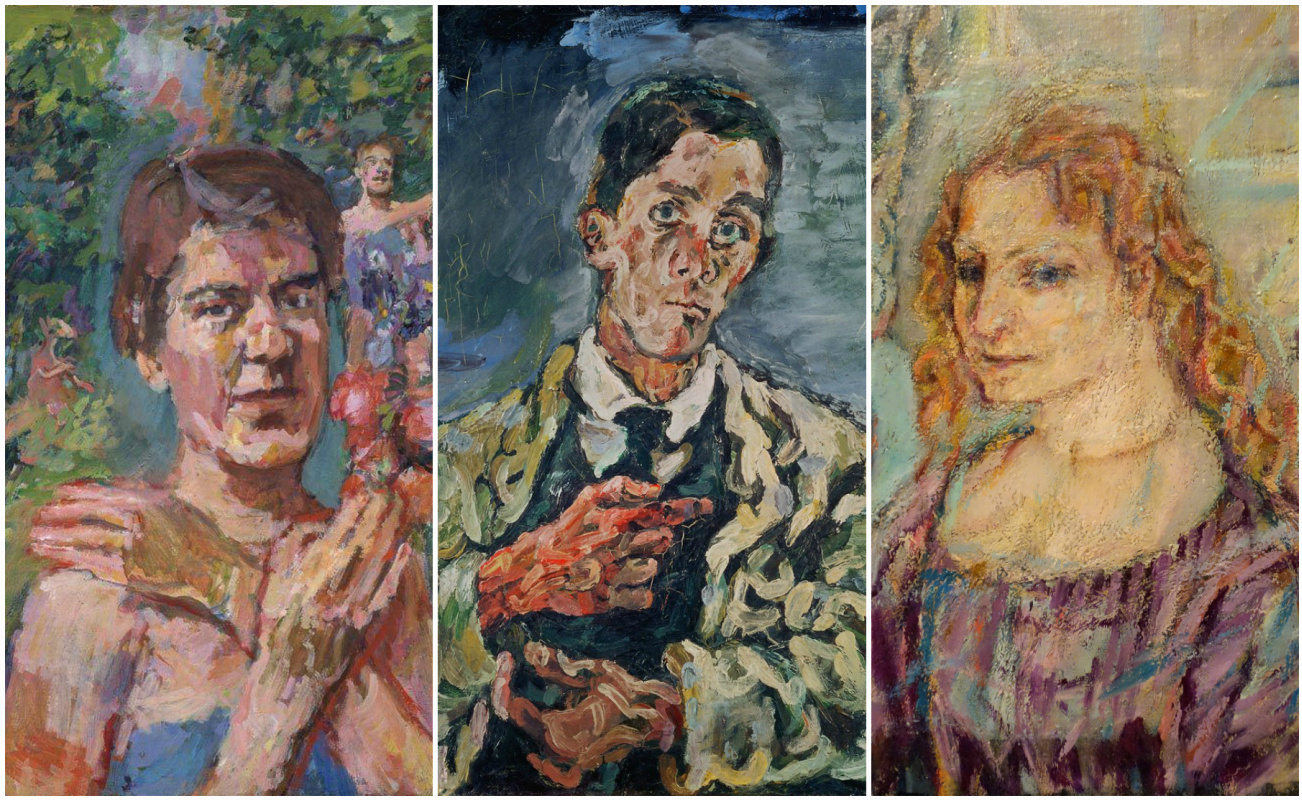

Oskar met Alma Mahler at the age of 26 and by that time, he had already participated in Klimt's exhibition of avant-garde artists and wrote and staged his outrageous play Murderer, Hope of Women, which caused a huge scandal. He was involved with the avant-garde journal Der Sturm and enlisted the strong support of the trendy architect Adolf Loos, who not only recommended Kokoschka to his rich customers, but also paid for his travels. Because of his provocative erotic drawings, Kokoschka was fired — first from a teaching position, and later — from Art workshops, where he used to draw sketches for postcards and illustrations for children’s books. He was on everyone’s lips: those of journalists, bohemian public in taverns and cabarets, wealthy bourgeois at garden parties. It was probably at one of these events where Carl Moll, Alma’s stepfather, heard about Kokoschka. Soon, the artist was commissioned to paint a portrait of the widow of the composer Gustav Mahler.

The Tempest

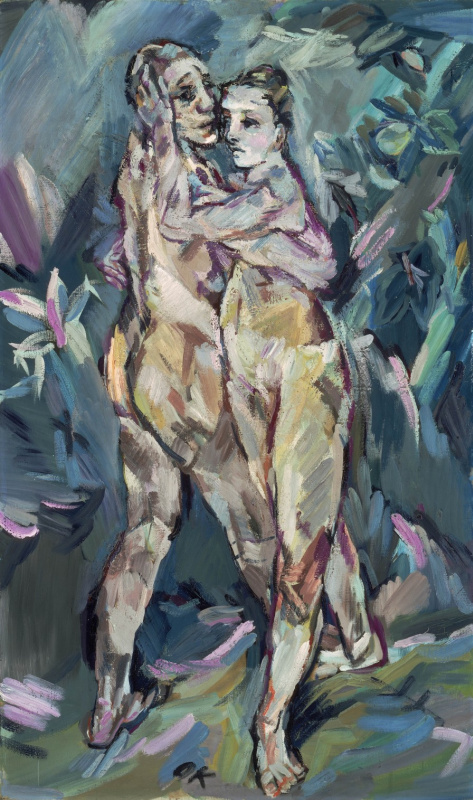

"How beautiful she was, how seductive behind her veil of dreams! I was enchanted by her!" recalled Kokoschka. He decided to depict Alma as Mona Lisa — those were the years of the sensational world-wide fame of Leonardo's painting: in 1911, it was stolen from the Louvre, its' reproduction constantly appeared on the front pages of newspapers, while journalists kept making assumptions and theories. Within several years of searching, it became the most replicated and recognizable painting, the most mourned loss of the museum and the object of the most intriguing criminal story. So Alma had to be the new Mona Lisa.Kokoschka fell in love at their first meeting — and wrote a long letter containing love confession as soon as he got home. He was passionate, assertive, reckless, and seemed to be a really brilliant young man, which was quite important for Alma. Just in case, she didn’t stop her correspondence with one of her previous lovers, the architect Walter Gropius. And kept secret her relationship with Kokoschka — just in case as well. But rumors of such overwhelming love affairs are spread instantly. At the exhibition of the Berlin Secession, Gropius got to see the double portrait of Alma and Oskar with the title Engagement written under it. In the painting, their bodies are intertwined, almost joined like those of conjoined twins, his big hand carefully protects her hand while they are in bed, wearing robes. Everything was too obvious. And then Gropius himself put an end to their correspondence.

A soldier, a professor, a fetishist

When World War I began, it was enough for Alma to call Kokoschka a coward several times so that he enrolled in the 15th Imperial Dragoons, a crack cavalry regiment, and even decided that he did it voluntarily. He sold The Bride of the Wind to buy the best horse. He went to the photo studio and took a few pictures in his new shining uniform. And that was the end of the romantic part of his military career.

For several years, Oskar would be tormented by hallucinations and terrible memories, but his break with Alma Mahler made him suffer even more. He continued to paint her — and when her image faded from his memory, he ordered a doll, which had to resemble his beloved women as precisely as possible. In the evenings, he dressed up the rag Alma in silk and lace and took her with him to the opera and parties. And during the day, he taught at the Dresden Academy of Art. He also travelled and painted a lot, which made his pain gradually subside.

But she didn’t — and got married for the third time. With the writer Franz Werfel. During the reign of the National Socialists, she and her husband fled to America — and in the end, turned out to be completely unhappy in their marriage. A Jewish husband, even though a talented and famous one, often got on Alma’s nerves just by his physical presence, and she started taking a liberty of going on anti-Semitic rants at friendly dinners. She spent the rest of her life making money off copyrights for Mahler’s music and Werfel’s novels.

After his break with Alma, Oskar Kokoschka was single for 20 years — and met his future and only wife at the age of 50.

Viennese pie recipe

In the 1920s, Kokoschka traveled to Europe, Asia and North Africa. He quit his career as a teacher at the Dresden Academy, visited Paris, and finally got to Prague in 1934. Kokoschka’s father was a Czech; his sister lived in Prague since 1919. What’s more, a year before that trip, Czech gallery owner Hugo Feigl held a personal exhibition of the artist — and it enjoyed great success. Kokoschka went to a city in which he could easily find friends and fellow-thinkers, but had no plans to stay there. He wanted to go as far as possible: the Far East would be a nice place to flee from the new German government and the presentiment of an inevitable catastrophe.Kokoschka spent four years in Prague, painting dozens of amazing views of the city from his favorite point of view — through the eyes of a bird hovering over the city. He created an association of creative people in that city, learnt that his paintings had been confiscated from German museums and participated in the Degenerate Art exhibition and heard in one of the radio programs that the German authorities promised to hang him on the first lamppost as soon as they get to Prague. It was there, where he finally met young Oldriska Aloisie (Olda) Palkovská at a dinner in the house of her father, a lawyer and a great connoisseur of art.

When, according to the Munich Agreement, part of Czechoslovakia was given to Germany in 1938, Olda and Oskar decided to leave Prague. It was no longer safe for the "degenerate" artist to stay in that city. They moved to London together — and in spite of the difficulties looming over Europe as a whole, Oskar Kokoschka’s personal notes became calm and peaceful for the first time in many years. For the first time, he stopped thinking about death and being afraid — he wrote about his new partner cooking a delicious rice pudding and chocolate Viennese pie. Every evening they went out to watch a movie in the cinema next door, discussed their favorite directors and walked.

They spent the whole war in London, became British citizens and got married in an air-raid shelter in Hampstead in 1941. Oskar Kokoschka’s work Christ helps the starving children was posted in London underground stations — in memory of the children who died of cold and hunger during the war and as a call to donate to charity in order not to let the rest die.

After the death of her husband, Olda Palkovská took all his diaries and letters and gave them to the Zürich Central Library. For the remaining years, she devoted herself to searching, buying, and collecting manuscripts, sketches, and photographs of her husband. She donated every new discovery to the library archive, and later — to the Foundation in memory of Oskar Kokoschka, which she founded herself.

When it comes to Alma Mahler, recalling Kokoschka in her autobiography, she stated that he had not painted anything worthwhile after the break with her.