Edvard Munch film, directed and written by English director and screenwriter Peter Watkins, was filmed in 1974 for Norwegian television. This is the case about which one can almost certainly say "you definitely have not seen such a biopic". A meticulous, historically accurate study

of one decade of Munch’s life in the mocumentary genre. This is a fantasy on the theme "What would a documentary film about Munch and his era look like if there were documentary films in those years".

For Peter Watkins, the mocumentary genre, which also features non-professional actors, is a trademark, a personal area of experiments and international awards. In the same genre, he shot films about the Jacobist uprising of the 18th century, the war in Vietnam and the Paris Commune. And he tried to select amateur actors in each case not only according to their appearance, but also according to their place of birth, political views corresponding to the character.

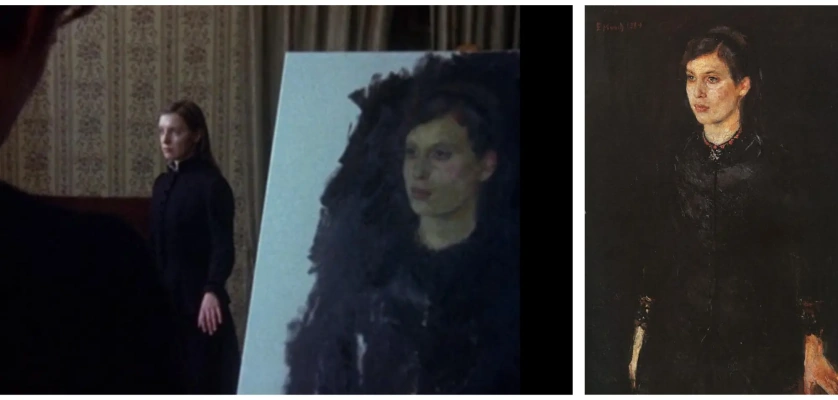

A still from the movie. Edvard Munch and his first lover Fru Heiberg

The Edvard Munch film is a slow, often silent cutting of close-ups of the actual history of the artist’s formation interspersed with pseudo-interviews with the story heroes and others. Invisible journalists seem to be interviewing Christiania’s impoverished families, where even children work in factories, Munch’s brother and sister, women and men from the radical anarchist community. Casual visitors to the artist’s exhibition or a critic who published an article about him in the early 1890s give interviews; Munch’s colleagues gossip about him in a smoky bar. The voice-over is the voice of Watkins himself; from time to time, he reads about important events that happened in the world in the current year, and accompanies episodes from the artist’s life with quotes from his diaries.

Left: a still from the film. Right: Edvard Munch. Sister Inger, 1884

Left: a still from the film. Right: Edvard Munch. The Sick Child, 1885

With the help of virtuoso cinematic techniques, Watkins managed to create visual images that are synonymous with the artist’s mental disorders. Ambitious, energetic, tormented by demons, Munch is silent or whispering for so long that his high hysterical voice in the first tense moment looks almost a miracle, akin to a deaf-mute speaking. The camera follows the hero relentlessly, but sometimes he turns around, staring directly into it, as if a ghost is chasing him. One of the most painful moments in the artist’s life, the illness and death of his beloved sister, stretched out throughout the film. Fragmentary and varied memories from his childhood over time come down to only one thing: Edward’s sister coughing up blood and he himself coughing up blood, 13-year-old boy who suffered a serious illness, but survived. This memory haunts the viewer with such obsession that he must understand: it was that much obsessive and relentless for Munch himself.

The moments, in which the camera moves slowly and stops on the surface of Munch’s paintings, are the most valuable for understanding his art.

These close-ups work better than any art history article: scratches, nervous strokes, lumps of paint and sweeping furrows allow us to understand exactly how Munch invented Expressionism and what Expressionism

really is.

Artists mentioned in the article

We recommend reading