Fact 1. The Superstar

The biography of Artemisia Gentileschi formed the basis for articles, films, plays, novels and, of course, life stories. The most recent one was released in September 2020. It is titled Artemisia Gentileschi and Feminism in Early Modern Europe by renowned art historian Mary Garrard. In 2021, British studio ViacomCBS will launch a series based on her previous book. It will be produced by Frida Torresblanco, best known for her Oscar-winning film, Pan’s Labyrinth. The large retrospective at the National Gallery in London, the opening of which was postponed from spring to October due to the pandemic, became one of the most notable events in the world cultural life of 2020.This is a great path for an artist who was’t really noticed until the beginning of the 20th century (however, let’s face it, Caravaggio wasn’t either).

Fact 2. The Prodigy

Artemisia’s mother died when her daughter was 12 years old, and left the girl to care for her father and three surviving younger brothers. The father, according to contemporaries, was a loner: rude, sarcastic, domineering spender and libertine. But at least he taught his daughter painting.Between cooking, cleaning, sewing and washing, Artemisia ground pigments, took her brushes and maulstick, and copied, copied, copied her father’s artworks. She could not study on par with boys of her age, make sketches on the streets of Rome, attend the Academy or portray models. Her early nudes are shapeless, like ice cream melting in the sun. "Staying at home hurt me," Artemisia said later.

Fact 3. Rape and trial

The earliest known painting by Artemisia is Susanna and the Elders (1610). It was created when the artist was only 17 years old. The work is sometimes called prophetic: we know that in May of the following year, the girl was raped by Agostino Tassi, a colleague of her father, who was hired to train the young artist. After the villain refused to marry Artemisia, Orazio reported Tassi to the authorities. The subsequent trial is recorded in documents discovered in 1876 in great detail. These protocols are a vivid illustration of the terrible treatment of women in Rome in the early 17th century.Artemisia Gentileschi, Susanna and the Elders (1610). Weißenstein palace, Bavaria

Tassi was previously tried for incest with his sister-in-law, and was also accused of trying to shoot his pregnant mistress. However, the attack on Artemisia could only be regarded as a crime if it was proved that she had lost her virginity — then it would be considered causing damage to property. There was no question of any personal injury.

Tassi’s lawyers claimed that Artemisia was a libertine who wandered all over Rome and posed for her father naked at the open window. She was subjected to a humiliating gynaecological examination in public. And afterwards she was tortured with a taut rope wrapped around her fingers, which was especially cruel for the aspiring artist, in order to confirm the testimony. She said over and over again, "It's true, it’s true, it’s true". Her words were recorded in the minutes, which are also on display at the National Gallery in London — for the first time outside the Roman State Archives.

Fact 4. The dependent husband

Today, the art and life of Artemisia Gentileschi is often reduced to the rape and subsequent trial. However, these are not the only significant episodes in her history.Although Tassi was found guilty and sentenced to exile from Rome (but never left the city), Artemisia’s honour was damaged. Orazio married her to Pierantonio Stiattesi, a mediocre artist and top-flight dependent. The "sweetener" was his dowry of a thousand scudi. It is no surprise that the marriage did not last long.

The spouses moved to Florence in 1613, and for the next seven years, Artemisia was almost always pregnant (but never in debt). Unfortunately, three of her children died before they turned one year old. Another boy, Cristofano, died at the age of five. Only her daughter Prudentia grew up, Artemisia named her after her mother. Subsequently, the girl became an independent artist, but nothing is known about her work.

Fact 5. The lover

In 2011, 36 letters were found dating from around 1616—1620. They testify that Artemisia had a passionate affair with a wealthy Florentine nobleman named Francesco Maria Maringhi. Pierantonio knew about this relationship and wrote to his wife’s heartfelt friend on the back of her love letters. Apparently, he condoned their relationship, as Maringhi provided financial support to the couple. However, by 1620, rumours spread at the Florentine court, and Artemisia and her husband had to return to Rome.She had a passionate correspondence with her lover for some time, but it gradually faded away. And by 1623, any mention of Pierantonio Stiattesi had disappeared from all documents. Most likely, Artemisia simply left her freeloader husband and took her daughter with her. Considering that European women were not allowed to own property or be the custodian of their own children at that time, this is an overwhelming act.

Fact 6. The prominent figures

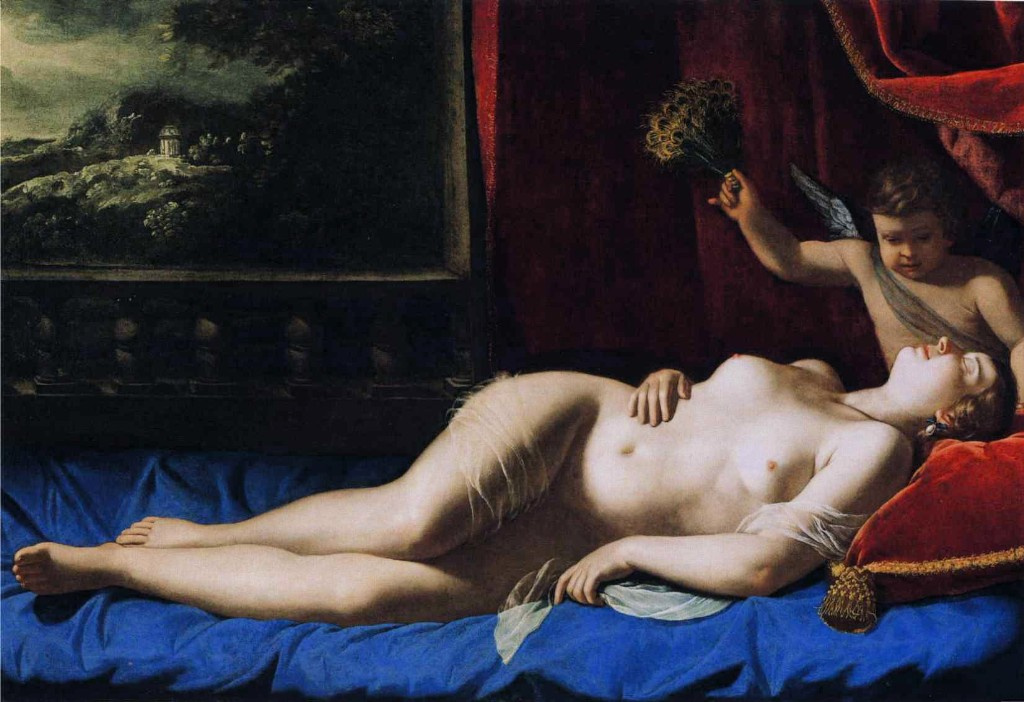

Artemisia Gentileschi became the first woman to be admitted to the Academy of Arts in Florence. As an artist, she could paint naked models of her sex. This gave her an advantage over her male colleagues, who were forbidden to paint nude from live female models. And do not forget that women were not supposed to pick up a brush at all at that time.Artemisia knew Galileo Galilei, both were members of the Academy and were associated with the Grand Ducal Court of Florence. She must have learned some knowledge from the scientist. Thus, the blood splatters in the Judith Beheading Holofernes painting (c. 1620) is consistent with his discovery of the parabolic path of projectiles.

She created a panel titled Attraction commissioned by Michelangelo Buonarotti the Younger (a relative of the great artist) in the Buonarotti house in Florence. It is significant that her first art exhibition was held in this building in 1991.

Fact 7. The letters

Artemisia Gentileschi, Self-Portrait as the Allegory of Painting (1630s). Royal Collection, Windsor

In 1630, Artemisia Gentileschi moved to Naples, where she settled for the rest of her life (except for her short trip to London). She carried on a fairly extensive correspondence with her patrons and friends, including Galileo. Most of the correspondence concerned professional issues, such as payments, orders and paintings, which the artist sent throughout Europe, hoping to find a permanent job. She complained bitterly about the high cost of living in Naples and the constant financial difficulties, but her career nonetheless flourished. Artemisia ran a successful studio in Naples, where she most likely taught her daughter Prudentia.

Determined to be on par with her male colleagues, Artemisia assured that "the woman’s name arises doubt until her work is seen," while her creations "will speak for themselves". Just a few months later, she wrote a phrase that has become popular these days: "I will show your lordship what a woman is capable of."

Fact 8. The prices

In the 1500s and 1600s, there were few artists among women. Artemisia’s contemporaries were Sofonisba Anguissola, Fede Galicia and Lavinia Fontana. However, Gentileschi was undoubtedly the most talented. Her artworks have stood the test of time, which is evidenced by the auction prices.Thus, the fairly recently discovered painting, Mary Magdalene in Ecstasy, was estimated at about $ 300 thousand in 2014, and sold at auction for 1.1 million. Most likely, Gentileschi presented herself as a saint — possibly after winning the rape trial.

At the moment, the record holder among Artemisia’s paintings is Lucretia, which was put up for sale in November 2019. The Parisian Artcurial auction house tentatively estimated it at 600 to 800 thousand euros, but the final price was 4.8 million (6.1 million dollars).

However, these amounts are negligible compared to the cost of the works by her male contemporaries. Thus, the Danae scene by the artist’s father, Orazio, was auctionned in 2016 for more than $ 30 million. Fortunately, Artemisia surpassed her parent, not in auction prices, but in fame.