До двадцати пяти лет Исаак Левитан писал только Москву и Подмосковье. География его пейзажей не расширялась по очень простой, банальной и грустной причине – художник был беден, почти нищ и не мог позволить себе дальних переездов. Ранней весной 1886 года, заработав первые серьёзные деньги за декорации для спектакля Частной оперы Саввы Мамонтова, Левитан, окрылённый возможностью вырваться за пределы привычного мира, впервые в жизни едет в Крым.

The illustration above: Isaac Levitan. Street in Yalta, 1886.

Levitan did not keep a diary, and the details of his stay in Crimea are still fragmentary even for the most meticulous biographers. It is believed that the artist visited Yalta and Gurzuf, Massandra and Alupka. He was young and extremely impressible, and the southern nature, which was so different from the Moscow region that was familiar to his eye and brush, at first could not but shake Levitan. Everything was different — landscape, vegetation, colour intensity. There a new, previously poorly imagined reality opened up — rocks, Tatar saklias, the sea.

“Dear Anton Pavlovich, damn it, it is so nice here!” Levitan wrote enthusiastically to his friend Chekhov. “Now imagine bright greenery, blue sky, and what a sky! Last night I climbed a cliff and looked out to the sea from the top, and you know what — I cried, I cried bitterly; this is the place of eternal beauty and this is where man feels his complete insignificance.”

Levitan spent one and a half to two months in Crimea. We can only guess, with whom he communicated, where he visited, where he lived, what he saw and felt. But already at the end of April 1886, he sent a letter to Chekhov from Alupka, which evidences that Levitan’s mood had seriously changed:

“Forgive me, my dear Anton Pavlovich, for not writing to you for so long. I didn’t write to you because I am already very lazy to write letters, and besides, I was going to move any day. Now I have settled in Alupka. I am extremely tired of Yalta, there is no society, i.e. no acquaintances, and the local nature only amazes at first, and then it becomes terribly boring and I really want to go north. I moved to Alupka because I did not work much in Yalta — and yet a new place, which means I am to absorb new impressions enough for a while, and then I will certainly go to Babkino (to see your vile face). Just one more thing, tell me, where did you get the idea that I went with a woman?..”

Already in mid-May, Levitan, fed up with impressions and yearning for the “sweet north”, would leave Crimea so that he forget it for almost a decade and a half. The next time he would only come to Yalta in 1900, a few months before his death, to say goodbye.

It could be argued that Crimea did not leave significant traces in Levitan’s work, remained an insignificant episode in his biography, if not for one fact: the Crimean sketches made in the spring of 1886 would appear extremely successful — viewers and connoisseurs would buy them right from the exhibition. And they would talk about Levitan as about the person who opened the “new Crimea” for the Russian public.

Levitan did not keep a diary, and the details of his stay in Crimea are still fragmentary even for the most meticulous biographers. It is believed that the artist visited Yalta and Gurzuf, Massandra and Alupka. He was young and extremely impressible, and the southern nature, which was so different from the Moscow region that was familiar to his eye and brush, at first could not but shake Levitan. Everything was different — landscape, vegetation, colour intensity. There a new, previously poorly imagined reality opened up — rocks, Tatar saklias, the sea.

“Dear Anton Pavlovich, damn it, it is so nice here!” Levitan wrote enthusiastically to his friend Chekhov. “Now imagine bright greenery, blue sky, and what a sky! Last night I climbed a cliff and looked out to the sea from the top, and you know what — I cried, I cried bitterly; this is the place of eternal beauty and this is where man feels his complete insignificance.”

Levitan spent one and a half to two months in Crimea. We can only guess, with whom he communicated, where he visited, where he lived, what he saw and felt. But already at the end of April 1886, he sent a letter to Chekhov from Alupka, which evidences that Levitan’s mood had seriously changed:

“Forgive me, my dear Anton Pavlovich, for not writing to you for so long. I didn’t write to you because I am already very lazy to write letters, and besides, I was going to move any day. Now I have settled in Alupka. I am extremely tired of Yalta, there is no society, i.e. no acquaintances, and the local nature only amazes at first, and then it becomes terribly boring and I really want to go north. I moved to Alupka because I did not work much in Yalta — and yet a new place, which means I am to absorb new impressions enough for a while, and then I will certainly go to Babkino (to see your vile face). Just one more thing, tell me, where did you get the idea that I went with a woman?..”

Already in mid-May, Levitan, fed up with impressions and yearning for the “sweet north”, would leave Crimea so that he forget it for almost a decade and a half. The next time he would only come to Yalta in 1900, a few months before his death, to say goodbye.

It could be argued that Crimea did not leave significant traces in Levitan’s work, remained an insignificant episode in his biography, if not for one fact: the Crimean sketches made in the spring of 1886 would appear extremely successful — viewers and connoisseurs would buy them right from the exhibition. And they would talk about Levitan as about the person who opened the “new Crimea” for the Russian public.

In the Crimean mountains

1886, 36.5×67 cm

“Postcard Crimea” before Levitan

It is easier to understand what was the “new Crimea” discovered by Levitan, if you know how did a common art lover imagine Crimea.

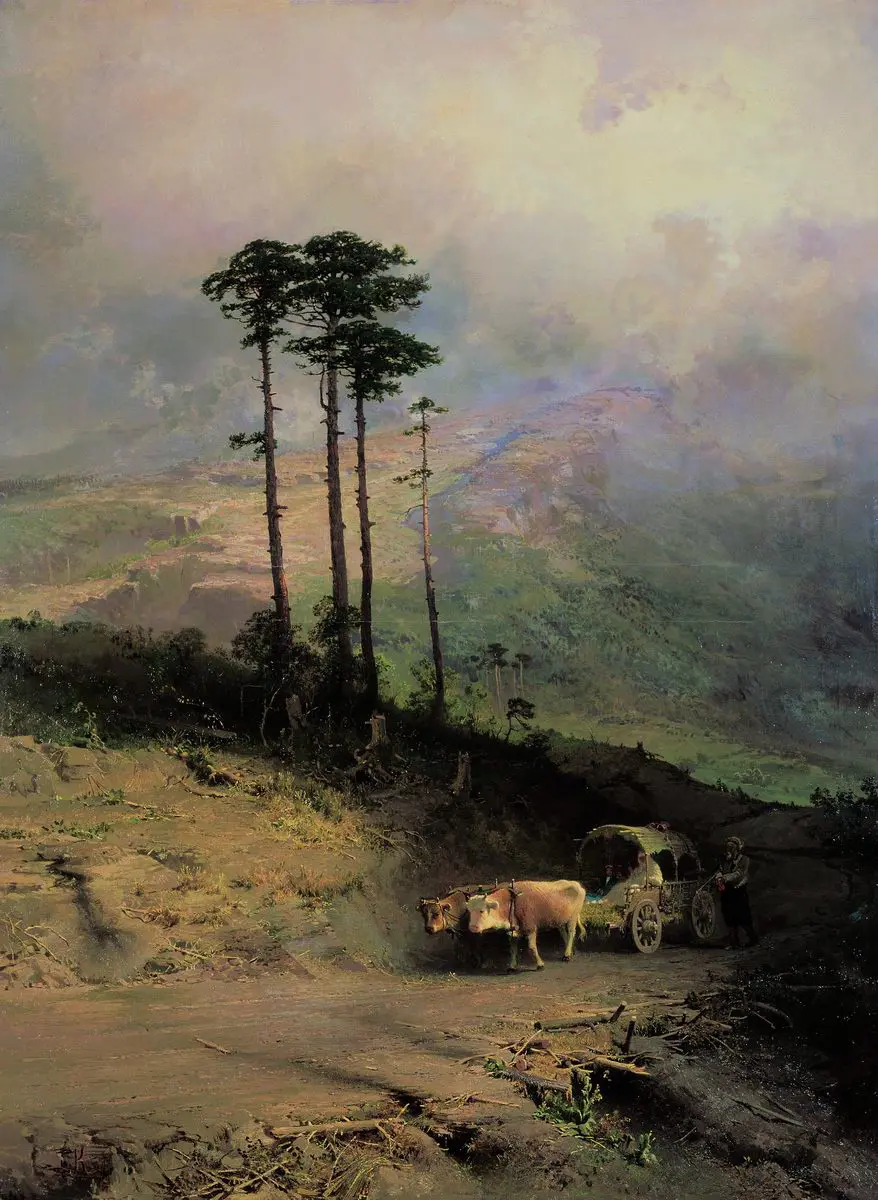

It would be lies to say that the Russian public did not know the picturesque Crimea before Levitan. There was Aivazovsky’s Crimea — solemnly elevated, romantic, and alas, mercilessly replicated in the later years of the artist. There was also a ceremonial Crimea, blooming, radiant and correct, pretty idealized — just ready to print on postcards and send it to young ladies with love. Such a picturesque Crimea is usually called the “postcard” Crimea. Such Crimea would be painted by artists Gabriel Kondratenko, Vladimir Orlovsky, Joseph Krachkovsky both before and after Levitan. They bought such products willingly to revive their interiors.

The “genius young man” Fyodor Vasilyev tried to overcome the textbook beauties of the Crimea in his work, but he died too early and did not manage to do too much.

In the Crimean mountains

1873, 116×90 cm

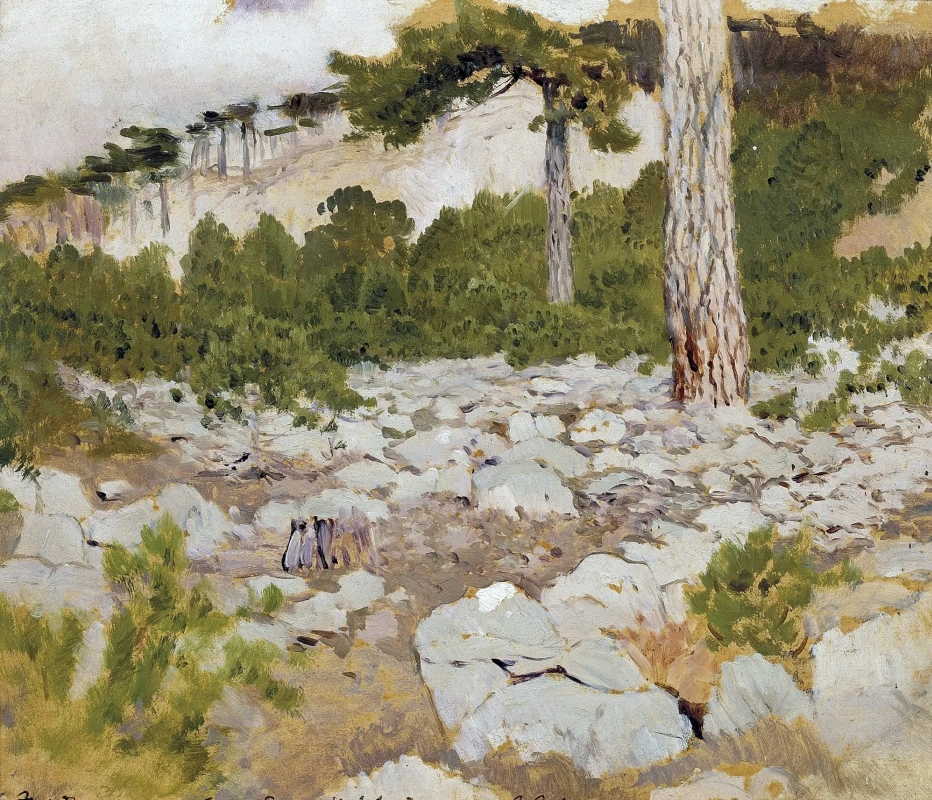

The fresh look of Levitan

Levitan saw a completely different Crimea — not postcard or ceremonial, or “glossy”.

In his Saklia in Alupka, Tatar Cemetery or sea views, there is neither pathetic pressure, nor romantic pompousness, nor special “beauties”. According to art historian Vladimir Petrov, the Crimean landscapes by Levitan “are imbued with a sense of calm, thoughtful contemplation”.

Tatar cemetery. Crimea

1886, 45×75.2 cm

At the beach. Crimea

1886, 41.3×65 cm

One of the most interesting Levitan’s works of his Crimean period is Saklia in Alupka, which is kept in the Tretyakov Gallery. These irregular lines, rough boards and bulky raw stones are very far from the usual Crimean “palace pathos”; at the same time, there is so much radiance and lightness in this cheerful combination of light blue and ocher, sand and sky. There are so many new colouristic possibilities in comparison with the earthy-green palette of Levitan’s early Zvenigorod and Ostanskino landscapes! “Working in the Crimea in the open air gave Levitan a lot, contributed to the enrichment of his palette, the development of his sense of colour,” says the artist’s biographer Alexei Fyodorov-Davydov.

Hut in Alupka

1886, 19×33 cm

“Levitan... was fascinated by the beauties of the southern nature, by the sea, flowering almonds,” testifies the artist’s friend Mikhail Nesterov. “The elegiac motives of ancient Taurida with its opal sea, pensive cypresses, and the soft outline of the mountains corresponded with the gentle, melancholic nature of the artist as much as possible. Upon his return to Moscow, Levitan put his Crimean sketches at the Periodic Exhibition, which was the most popular after the Travelling Exhibition at that time. The sketches were sold out in the very first days...”

The sea coast (Crimea)

1886, 30×40 cm

Grey day. Mountains. Crimea

1886, 33×65 cm

Crimea. In the mountains

1886, 20×23 cm

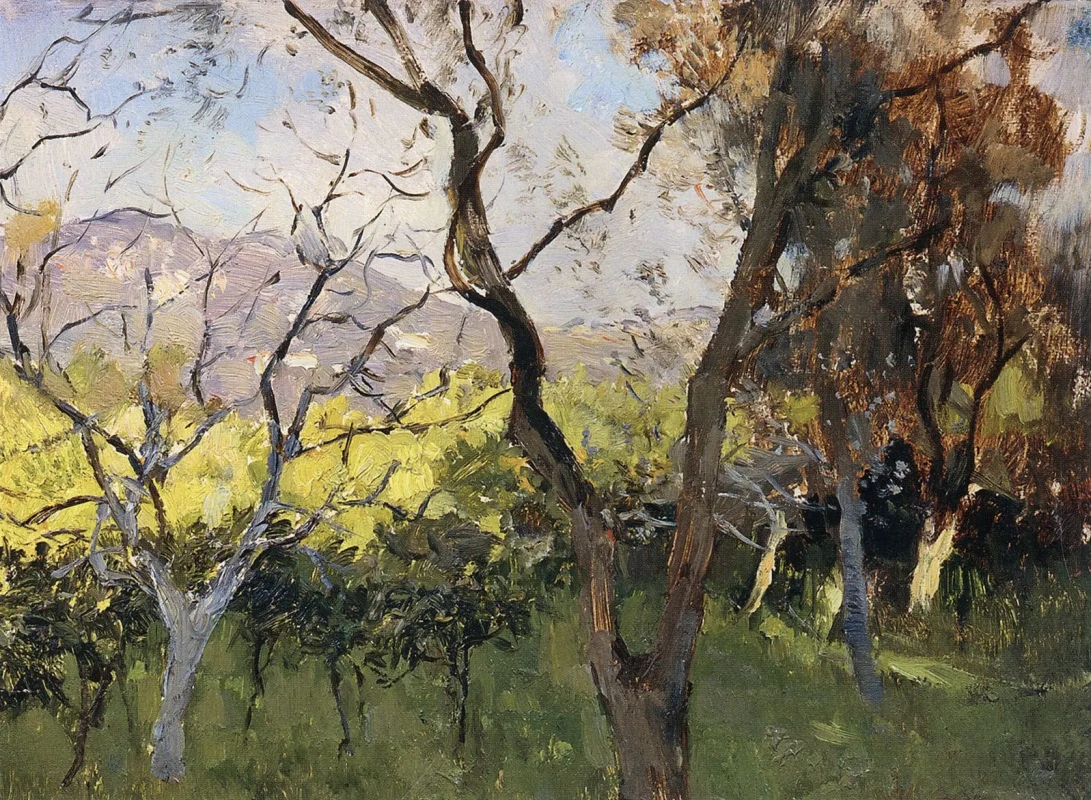

Garden in Yalta. Cypress

1886, 20×32 cm

When the teacher of Levitan at the Moscow School of Painting, Sculpture and Architecture, the artist Vasily Polenov, found himself in the Crimea a few years later, he was amazed at how accurate, subtle and faithful to nature turned out to be Levitan in his Crimean sketches:

“The more I walk around the outskirts of Yalta,” Polenov admitted, “the more I appreciate Levitan’s sketches. Neither Aivazovsky, nor Lagorio, nor Shishkin, nor Myasoyedov gave such truthful and characteristic images of the Crimea as Levitan.”

“The more I walk around the outskirts of Yalta,” Polenov admitted, “the more I appreciate Levitan’s sketches. Neither Aivazovsky, nor Lagorio, nor Shishkin, nor Myasoyedov gave such truthful and characteristic images of the Crimea as Levitan.”

The patio in Yalta

1886, 19×32 cm

View near Yalta

1886, 27.8×38.3 cm

In most cases, Levitan’s Crimean sketches never became material for his finished paintings. There are very few exceptions, such as the By the Sea. Crimea painting (State Russian Museum, St. Petersburg), grown out of the etude of the same name and significantly enriched in palette, and the Crimean Landscape (Plyos State Museum-Reservation of History, Architecture and Art, Plyos).

At the beach. Crimea

1886, 41.3×65 cm

Crimean landscape

1887, 73×97 cm

This picture, which synthesized many of Levitan’s Crimean impressions, depicts the mountainous coast of the Black Sea, colourful pebbles, moist stones greened with moss. The viewer’s gaze slides along the surf line into the distance, resting on the majestic outlines of Ayu-Dag with white saklias at its foot and overgrown cypresses. This is not a marine in the traditional sense — the sea is not the central sibject in the Crimean Landscape. Levitan always acutely experienced the vastness of water space and was emotionally suppressed by it (this was the case not only on the Black Sea, but also when the artist first came to the Volga), therefore he did not seek to capture the vastness or greatness of the sea. Rather, the sky is more important for his composition: these grey and yellowish thin clouds, extremely rich in shades, with bluish breakthroughs, perfectly convey the mood of a cloudy day of Crimean spring.

The staff of the Plyos museum housing the Crimean Landscape managed to see even images of people in the mottled foreground: “On the shore, there are two small figures, so rare in Levitan’s landscapes. He avoided depicting people or even genre scenes in his paintings, trying to “humanize” nature with his experiences and feelings. In the figures, a male and a female, one can guess the artist himself in a black suit and a red Turkish fez and his companion, most likely S. P. Kuvshinnikova.”

The staff of the Plyos museum housing the Crimean Landscape managed to see even images of people in the mottled foreground: “On the shore, there are two small figures, so rare in Levitan’s landscapes. He avoided depicting people or even genre scenes in his paintings, trying to “humanize” nature with his experiences and feelings. In the figures, a male and a female, one can guess the artist himself in a black suit and a red Turkish fez and his companion, most likely S. P. Kuvshinnikova.”

“January in Crimea. Winter comes to the Black Sea coast as if for fun...”

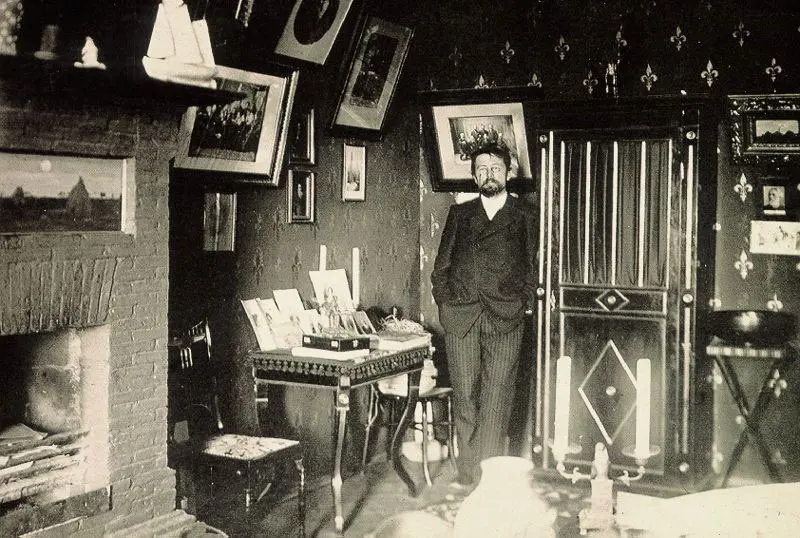

End of December 1899. The last days of the last month of the last year of the outgoing century. Thirteen years have passed since Levitan’s Crimean spring. All those years, he did not even think about Crimea — too many impressions layered, too much work, too stormy life he experienced seething with love passion and plunging into hopeless melancholy from time to time. He worked in the Moscow and Tver Governorates, explored and depicted the Volga, the Volga towns and monasteries, and became the most famous Russian landscape painter. He travelled abroad three times: he saw the works of the Impressionists in France, as well as his favourite artist Corot, he painted spring in Italy and the Mont Blanc mountain range, he was bored and shy again in front of the gloomy power of the sea and mountains in Finland.

But in the last days of the year and century, yet not knowing, but apparently anticipating that this will be the last year of his short 39-year life, Isaac Levitan went to Crimea.

We could loop the literal plot and say that Levitan was again called by the Crimean nature. However, in reality this was not the case. It was not nature, not rocks, not the sea, but people, his closest people in his entire life, attracted Levitan to the Crimea. Chekhov and his sister Maria Pavlovna, MaPa, as her family called her, the only woman Levitan made a marriage proposal to, the only one of all. It was them, Anton and Masha, his closest friends, that the terminally ill Levitan wanted to see.

We could loop the literal plot and say that Levitan was again called by the Crimean nature. However, in reality this was not the case. It was not nature, not rocks, not the sea, but people, his closest people in his entire life, attracted Levitan to the Crimea. Chekhov and his sister Maria Pavlovna, MaPa, as her family called her, the only woman Levitan made a marriage proposal to, the only one of all. It was them, Anton and Masha, his closest friends, that the terminally ill Levitan wanted to see.

In the photo from left to right: Isaac Levitan, Maria and Anton Chekhov.

A year earlier, Chekhov bought a land plot in Yalta. It was very high above the sea, next to the Tatar cemetery. He built a house there, the now famous White Dacha, gathering family and friends in his house, just as before. And on the wall in one of the rooms, among many other paintings and photographs, still hung the youthful portrait of sick Levitan painted by Chekhov’s elder brother Nikolai many years ago.

A year earlier, Chekhov bought a land plot in Yalta. It was very high above the sea, next to the Tatar cemetery. He built a house there, the now famous White Dacha, gathering family and friends in his house, just as before. And on the wall in one of the rooms, among many other paintings and photographs, still hung the youthful portrait of sick Levitan painted by Chekhov’s elder brother Nikolai many years ago.

Levitan came from the Moscow bad weather, dressed for winter frost, and the Chekhovs came to meet him without outerwear, joyful and friendly, as always. Crimean January seemed incredibly warm. Evergreens made you doubt that it was winter outside.

In Yalta, funny things happened with Levitan. He was sometimes loudly recognized on the streets — people already got used to Chekhov, but Levitan was a “visiting celebrity”. Once Chekhov took him to an art shop on the Yalta embankment. Looking at the roughly painted “beautiful” landscapes, Levitan was indignant: who needed such art and why did such things even exist?

When they left, Chekhov blamed Levitan for indelicacy — the pictures were painted by the owner of the shop, who was standing right there behind the counter. Levitan was horrified by his harshness, demanded to return immediately, trying to put on ease, he told the owner to hear that, in fact, everything is not so bad in these cute pictures, not so hopeless, and even glimpses of art... Sometimes he offended his loved ones, but Levitan could not offend someone intentionally on purpose.

In Yalta, funny things happened with Levitan. He was sometimes loudly recognized on the streets — people already got used to Chekhov, but Levitan was a “visiting celebrity”. Once Chekhov took him to an art shop on the Yalta embankment. Looking at the roughly painted “beautiful” landscapes, Levitan was indignant: who needed such art and why did such things even exist?

When they left, Chekhov blamed Levitan for indelicacy — the pictures were painted by the owner of the shop, who was standing right there behind the counter. Levitan was horrified by his harshness, demanded to return immediately, trying to put on ease, he told the owner to hear that, in fact, everything is not so bad in these cute pictures, not so hopeless, and even glimpses of art... Sometimes he offended his loved ones, but Levitan could not offend someone intentionally on purpose.

Chekhov on the balcony of his house in Yalta. 1899.

Photo: chekhov-yalta.org

Maria Pavlovna accompanied Levitan on long walks. She felt sorry for him: Levitan had grown very noticeably old, he tired quickly. The disease, aortic enlargement and rheumatic myocarditis, was pointless to hide behind jokes and cheerful chatter. Heart ailment betrayed itself with sunken eyes, yellowed face, and excruciating shortness of breath.

One day Levitan asked Masha to climb the mountains with him. He was unwell in the morning, his felt pressure in his heart and he explained:

“I really need to go there, higher, where the air is lighter, where it is good to breathe.”

They climbed the Yalta mountain: she was still as sweet and attractive as she once was, and he was slow, leaning on his stick with difficulty. Before Levitan a landscape was spreading similar to the one he saw on his first visit to the Crimea, when it overwhelmed him with its grandeur — the thick-coloured sea, merging with the boundless sky. And Levitan lost control of himself again:

“Marie! I don’t want to die so much. It is scary to die... And my heart, it hurts so much...”

They returned home, where the fireplace was lit, and Chekhov recalled over tea, laughing, how 13 years ago Levitan asked him in his letter to tell their common friend, architect Fyodor Shekhtel, that Levitan would not fall in love with southern nature and exchange the Moscow region for the Crimea: “Tell Shekhtel..., don’t worry, — I love the north now more than ever, I only now understand it...”.

Levitan smiled. He asked Masha to bring a piece of cardboard and paints. Masha herself was fond of painting, once she was Levitan's student (“Does Mlle Marie work?” he asked Chekhov. “Tell her to work a lot. Otherwise I will come and put her in a corner”). Paper and paint were brought quickly. That evening, on an elongated piece of cardboard, Levitan repeated his Haystacks painting. Since then, the picture has remained hanging in Chekhov’s living room, in an oblong niche above the fireplace.

Photo: chekhov-yalta.org

Maria Pavlovna accompanied Levitan on long walks. She felt sorry for him: Levitan had grown very noticeably old, he tired quickly. The disease, aortic enlargement and rheumatic myocarditis, was pointless to hide behind jokes and cheerful chatter. Heart ailment betrayed itself with sunken eyes, yellowed face, and excruciating shortness of breath.

One day Levitan asked Masha to climb the mountains with him. He was unwell in the morning, his felt pressure in his heart and he explained:

“I really need to go there, higher, where the air is lighter, where it is good to breathe.”

They climbed the Yalta mountain: she was still as sweet and attractive as she once was, and he was slow, leaning on his stick with difficulty. Before Levitan a landscape was spreading similar to the one he saw on his first visit to the Crimea, when it overwhelmed him with its grandeur — the thick-coloured sea, merging with the boundless sky. And Levitan lost control of himself again:

“Marie! I don’t want to die so much. It is scary to die... And my heart, it hurts so much...”

They returned home, where the fireplace was lit, and Chekhov recalled over tea, laughing, how 13 years ago Levitan asked him in his letter to tell their common friend, architect Fyodor Shekhtel, that Levitan would not fall in love with southern nature and exchange the Moscow region for the Crimea: “Tell Shekhtel..., don’t worry, — I love the north now more than ever, I only now understand it...”.

Levitan smiled. He asked Masha to bring a piece of cardboard and paints. Masha herself was fond of painting, once she was Levitan's student (“Does Mlle Marie work?” he asked Chekhov. “Tell her to work a lot. Otherwise I will come and put her in a corner”). Paper and paint were brought quickly. That evening, on an elongated piece of cardboard, Levitan repeated his Haystacks painting. Since then, the picture has remained hanging in Chekhov’s living room, in an oblong niche above the fireplace.

“We have Levitan,” Chekhov wrote to his wife Olga Knipper. “On my fireplace, he painted a moonlit night during haymaking. Meadow, stacks, forest in the distance, the moon reigns above.”

Photo: chekhov-yalta.org

Photo: chekhov-yalta.org

Twilight. Stack

1899, 59×74 cm

Levitan did not paint Crimea by his late impressions — the peninsula did not become “his” for him. At this time, the artist could only work supported with drugs and forcing himself. Having met the new year 1900 with the Chekhovs, in a couple of weeks he would sail from Yalta by steamer, return to Moscow, and be gone in the summer.

Several Crimean spring landscapes are dated by the last year of the artist’s life. They are executed in his late “impressionist” manner. They are like an unexpected memory of the distant spring of 1886, when Levitan, having first gained freedom from circumstances, escaped into the unknown Crimea.

Several Crimean spring landscapes are dated by the last year of the artist’s life. They are executed in his late “impressionist” manner. They are like an unexpected memory of the distant spring of 1886, when Levitan, having first gained freedom from circumstances, escaped into the unknown Crimea.

Spring in Crimea

1900, 55.3×71.7 cm

Spring in the Crimea. Etude

1900, 23.7×32 cm

Written by Anna Vcherashniaya