Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, once the primary witness to Montmartre’s golden age, well knew like a fan and patron of cabarets and brothels, and depicted his dissolute life and his surroundings swiftly and caricatured. But The Grand Palace (Grand Palais) in Paris decided to move away from this long-standing legend and instead focus on the artist’s works, his ambitions, his significance and his endless openness to the world, which he passionately studied and sang. Paintings are accompanied by letters, literature and original materials to form an original and complete retrospective.

Post-Impressionist French painter will be on display in the Grand Palais in Paris in a special retrospective, “Toulouse-Lautrec, Resolutely Modern.” Mentored first by Princteau, Bonnat and Cormon, and later by Manet, Degas and Forain, Toulouse-Lautrec had two distinct periods: one of naturalism and another more caustic. The exhibit explores these two periods and what links them through some 200 works.

Already at the age of 17, the young offspring of the aristocratic family, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec announced his intention to depict a “real, not ideal” world, after which he began to transform his energetic naturalism into a sharp and pungent style influenced by Japanese prints, photographs and impressionists.

Much more than just the more frivolous moments of the Belle Époque, Toulouse-Lautrec wanted to paint time, take hold of duration, find spacetime in images and freeze present, modern life, the entry into the 20th century.

Much more than just the more frivolous moments of the Belle Époque, Toulouse-Lautrec wanted to paint time, take hold of duration, find spacetime in images and freeze present, modern life, the entry into the 20th century.

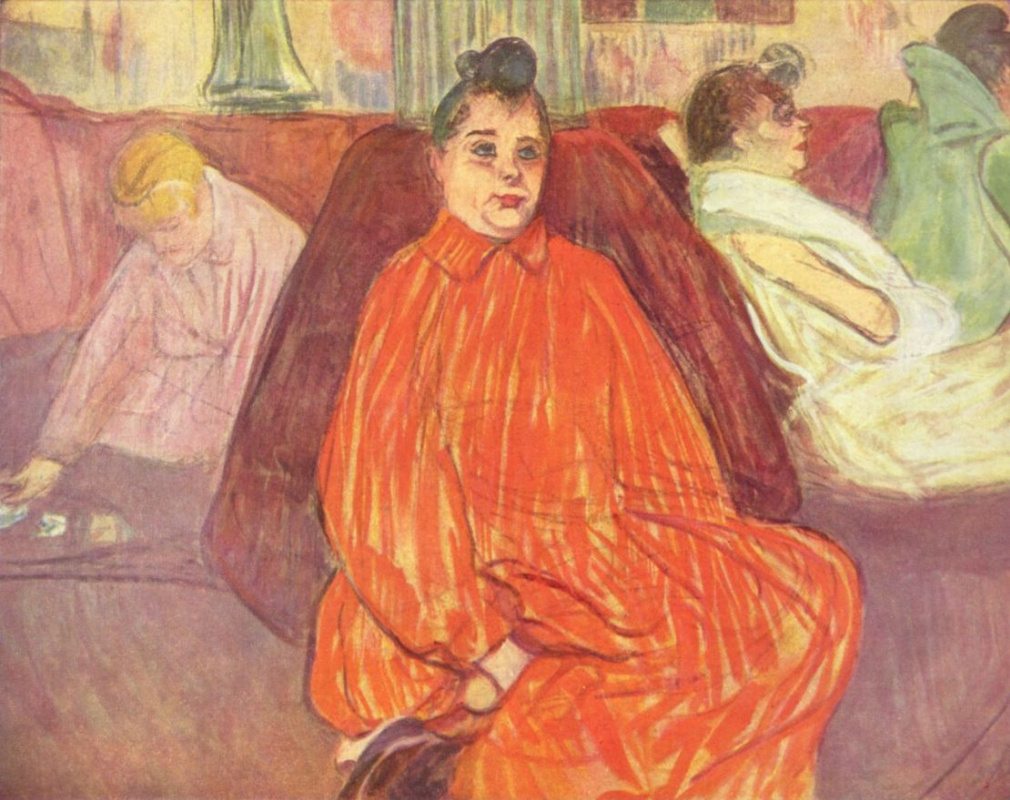

In the salon Divas

1893, 33×47.4 cm

It is the first Parisian retrospective of Toulouse-Lautrec since 1992, the date of the last French retrospective of the artist. Over the past two and a half decades, many exhibitions have explored the connections of Toulouse-Lautrec with the "culture of Montmartre", which he concurrently chronicled and criticised.

This sociological approach, satisfied with the story of the expectations and anxieties of that time, leveled Lautrec's artistic achievements. Meanwhile, he was never the accuser of urban vices and obscene rich people. By his birth, training and life choices, he saw himself rather as a pugnacious and comical interpreter, terribly human in the sense of Daumier or Baudelaire, of a freedom that needs to be better understood by contemporary audiences.

This sociological approach, satisfied with the story of the expectations and anxieties of that time, leveled Lautrec's artistic achievements. Meanwhile, he was never the accuser of urban vices and obscene rich people. By his birth, training and life choices, he saw himself rather as a pugnacious and comical interpreter, terribly human in the sense of Daumier or Baudelaire, of a freedom that needs to be better understood by contemporary audiences.

“We wanted to show works that had not been on display during the last retrospective in 1991, especially the first works and the last ones,” art critic Stephane Guegan said.

Born in Albi in 1864, Toulouse-Lautrec spent most of his life in Paris. He died in 1901, leaving behind between 700 and 800 paintings, 300 lithographs and 40 posters. At the end of 1886, Lautrec published several drawings in the press and thereby announced his future connection with posters, prints and illustrated books. He belonged to the “small boulevard”, a group of impressionists, in a bold style depicting the life of the working class.

He notably painted posters for the Moulin Rouge, the French cabaret famous for its high-kicking cancan dancers and flesh-exposing ostrich feather costumes, which first opened its doors to audiences exactly 130 years ago.

“The first works (were not shown then) because they are seen as too academic, which is a mistake, and the last works because they are deemed poor, which is another mistake,” added Guegan, also an advisor to the Musee d’Orsay.

By giving too much weight to the context and folklore of the Moulin-Rouge, we have lost sight of the aesthetic, poetic ambition which Lautrec invested in what he learned from another painters. As evidenced by his correspondence, from the mid- 1880s, he transformed his powerful naturalism into a more incisive and caustic style thanks to famous impressionists. Yet there was no linear, uniform progression, and true continuities are observed on both sides of his short career.

One of them is the narrative component from which Lautrec strayed much less than one might think. It is particularly clear in his approaches to death, around 1900, when his vocation as a historical painter took a desperate turn. The other dimension of the work that must be attached to his training is the desire to represent time, and soon to deploy duration as much as freeze momentum. Encouraged by his photographic passion and the success of Degas, electrified by the world of modern dancers and inventions, Lautrec never ceased to reformulate the space-time of the image.

One of them is the narrative component from which Lautrec strayed much less than one might think. It is particularly clear in his approaches to death, around 1900, when his vocation as a historical painter took a desperate turn. The other dimension of the work that must be attached to his training is the desire to represent time, and soon to deploy duration as much as freeze momentum. Encouraged by his photographic passion and the success of Degas, electrified by the world of modern dancers and inventions, Lautrec never ceased to reformulate the space-time of the image.

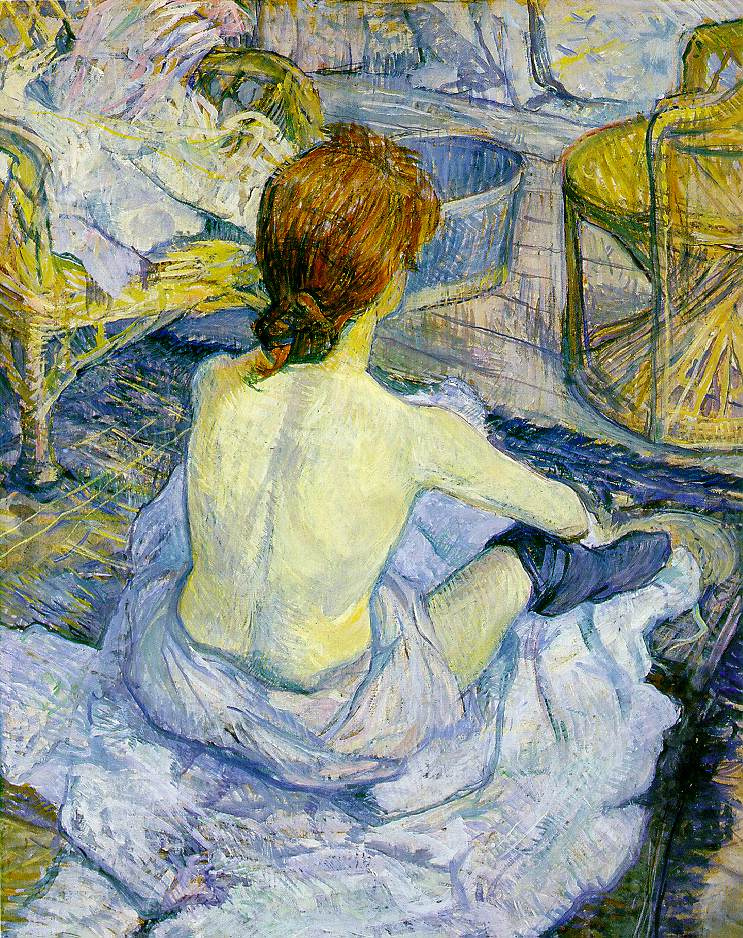

Restroom

1890, 67×54 cm

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, La Toilette, also known as Rousse (1889). Musée d'Orsay, Paris

At that time, the artist was literally obsessed with Carmen Gaudin - a girl with bright red hair (to whom Lautrec was interested on the verge of passion). He explored it in a kind of endless photographic cycle, each time trying to open a new perspective. It is assumed that the painting "La Toilette" (1889) depicts Carmen's neck and back. The woman, her back to the viewer, the unusual perspective and viewer’s angle, is how Toulouse-Lautrec brought reality to life. Like Degas, he portrayed women without any glamour or idealization, their true essence radiating from the line, composition, and color. In turn, the portrait of Jeanne Wenz “À la Bastille” refers to the work of Jules Bastien-Lepage.

À la Bastille

1889, 72.5×49.5 cm

In February 1888, his works were shown in Brussels at the Exposition des XX (the Twenty), an avant-garde association, and in Paris at the Salon des Indépendants. Among them was the work “In the Circus Fernando: The Ringmaster” that the author himself considered a masterpiece. It depicts a young red-haired girl, preparing to stand on the back of a galloping horse and jump through a paper screen. His use of free-flowing, expressive line, often becoming pure arabesque, resulted in highly rhythmical compositions. Here everything is distorted and shortened, passed through the prism of acceleration, and Lautrec finds in ordinary people, whom he painted, unexpected grace and energy.

In the Circus Fernando: The Ringmaster

1888, 98×161 cm

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec (1864-1901) left a hugely dense body of work behind his legacy, the impact of which is just as powerful today as it was when he first produced it. If the artist wonderfully represented the electricity of the Parisian night and its pleasures, he was driven above all by the aesthetic ambition of translating the reality of modern society into its many faces.

Montmartre was the perfect place for Lautrec, who wanted to explore the animality and eccentricity of human behavior. In addition to the desire for pure hedonism, his works reveal passions for dancing, drinking and sex - they overcome social classes, providing the artist with new themes and dramatic forms. A theater of expectations unfolds in the space of paintings. The color emphasizes the quirkiness of artificial lighting, and the excellent pattern comes to life.

The cafés, cabarets, entertainers, and artists of this area of Paris fascinated him and led to his first taste of public recognition. He focused his attention on depicting popular entertainers such as Aristide Bruant, Jane Avril, Loie Fuller, May Belfort, May Milton, Valentin le Désossé, Louise Weber (known as La Goulue [“the Glutton”]), and clowns such as Cha-U-Kao and Chocolat.

At the Moulin Rouge

1895, 123×140 cm

Drinking heavily in the late 1890s, when he reputedly helped popularize the cocktail, he suffered a mental collapse at the beginning of 1899. After a series of episodes of violence, the artist's parents sent him to a sanatorium in Neuilly-sur-Seine. While there he was able to demonstrate his lucidity and power of memory by preparing a number of works on the theme of the circus.

By the time of discharge, he had made 39 workshops of circus scenes depicting clowns and horse stunts among empty bleachers. The paintings that he created after met a lot of warm reviews - the shiny blond hair of Miss Dolly, a waitress at the Star in Le Havre, the "Messalina" series, "An Examination at the Faculty of Medicine", and recent portraits. They testify to the ability of Toulouse-Lautrec to have a different approach to creativity and to declare their own independence and freedom.

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec was a complex character, who knew how to play on his infirmity and create a central place for himself in the ebullient Parisian life of the late 19th century. For many, he was the painter who truly captured the bohemian world, the scenes and the backstage of the cabaret, the swirl of lives being exotically lived. And, with this the first major retrospective in 25 years, the Grand Palais invites you to waltz into the heart of this prolific artist's masterpieces who, despite his death at the age of 36, left behind him some 737 paintings, 275 watercolours and 369 lithographs, and over 5,000 drawings.

The exhibition will be running from 9 October 2019 until 27 January 2020

An exhibition co-produced with the Musée d'Orsay, the Musée de l'Orangerie and the Réunion des musées nationaux, with support from the city of Albi and the Toulouse-Lautrec museum.

It also produced with the exceptional assistance of the Bibliothèque Nationale de France, holder of the entire lithographic work of Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec.

Main illustration: Yvette Guilbert Singing “Linger, Longer, Loo”, 1894, by Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec

Based on materials from official page La Grand Palais, Artnet, Art News.