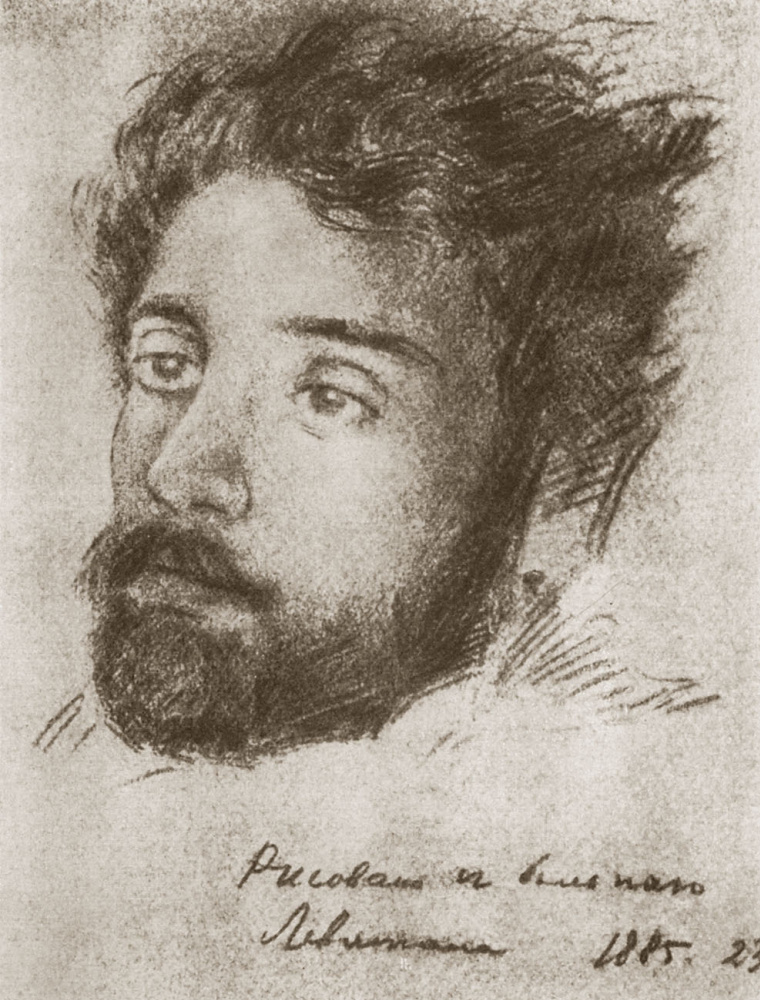

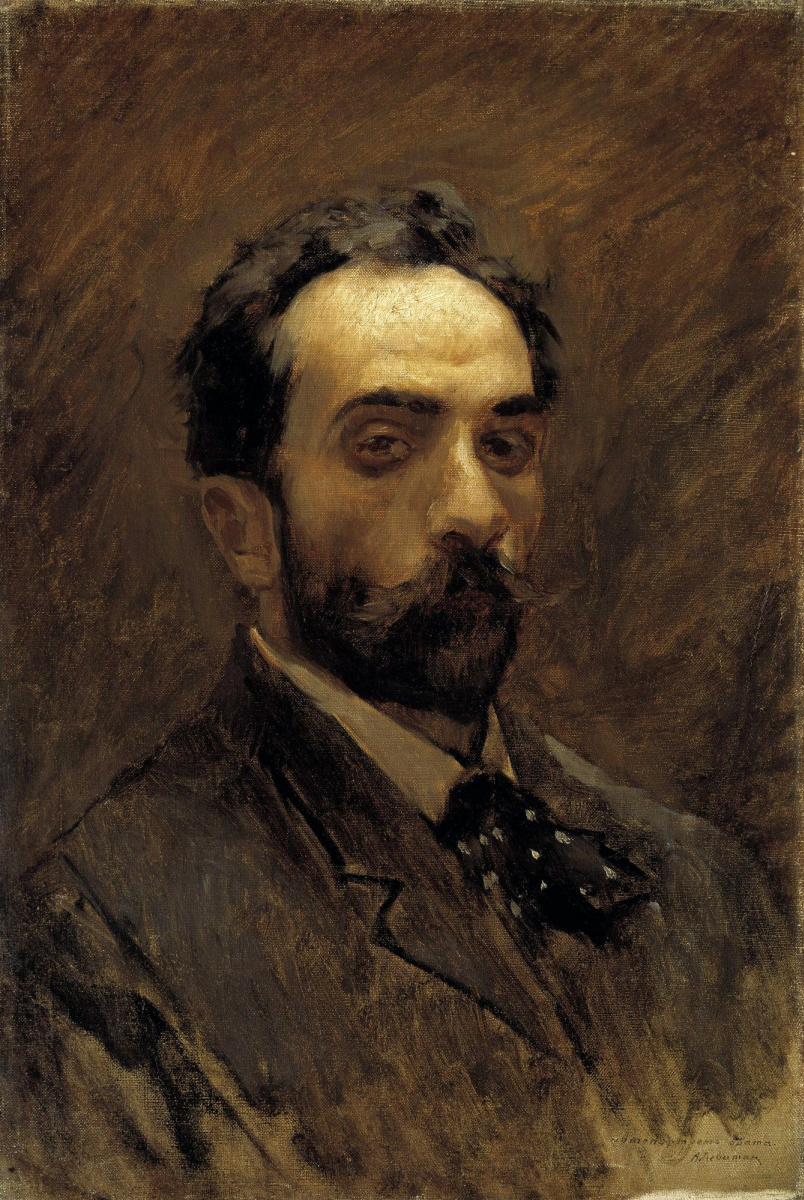

"Levitan was actually a man of a rare beauty," says the artist’s biographer Ivan Evdokimov. "The features of his swarthy face, as if tanned by the sun, were amazingly regular and subtle. The young man had dark curly hair. But Levitan’s main charm was in his huge, deep, black and sad eyes. It was impossible to pretermit his eyes, rare in beauty and expressiveness, even in a large crowd."

Isaac Levitan. Self-portrait, 1885. Tretyakov Gallery

Levitan possessed an appearance not only beautiful, but also extremely memorable. Tall and slender, he was being watched on the street. According to his contemporaries, in the theatre, all women’s eyes focused on Levitan, until the lights went out and the curtain opened. At railway stations, croquet venues, summer open-air concerts, the appearance of Levitan led to an inevitable consequence: necks turned towards him. Women who fell in love with the artist (and there were dozens of them) lost sleep and peace. Levitan’s outward attractiveness passed into a proverb among his acquaintances, the artist’s friend Anton Chekhov wrote sarcastically in his letters: "I will come to you, handsome as Levitan."

In short, there is nothing surprising in the fact that they always willingly drew and painted Levitan — his classmates Nikolai Chekhov and Alexei Stepanov, his teacher Vasily Polenov, his contemporary Valentin Serov. Arthive decided that gazing at the portraits of Levitan, created at different times and by different people, could be a good reason to tell about the artist’s life and his environment along the way.

In short, there is nothing surprising in the fact that they always willingly drew and painted Levitan — his classmates Nikolai Chekhov and Alexei Stepanov, his teacher Vasily Polenov, his contemporary Valentin Serov. Arthive decided that gazing at the portraits of Levitan, created at different times and by different people, could be a good reason to tell about the artist’s life and his environment along the way.

Role: ailing Levitan

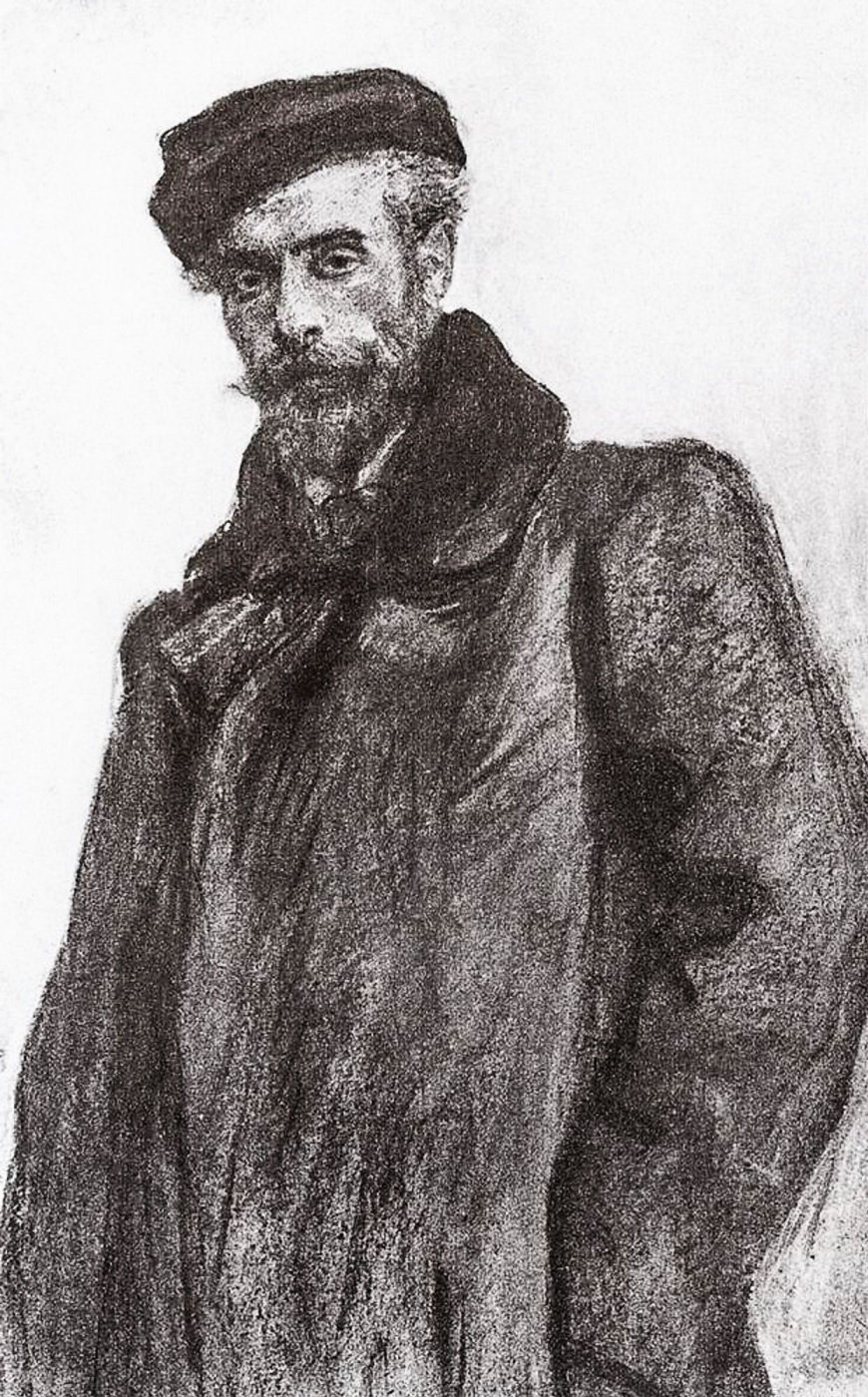

Who is the painter? Nikolai Chekhov

Circumstances of the creation. This sketch was made by Nikolai Chekhov, Levitan’s classmate at the Moscow School of Painting, Sculpture and Architecture, the elder brother of the writer.

Levitan was often ill — the main reason for this was his orphan youth, at times homeless and at first, completely impoverished. He caught typhoid twice in his life. For the first time — at the age of 17, along with his father. The sympathetic neighbours then took away delirious Elyash (Ilya) and Isaac Levitan to different Moscow hospitals, and only Isaac returned from there — his father died. The second typhus, in the late 1890s, exacerbated his heart disease and brought his death closer, while he has not yet turned forty. Between those extreme cases, Levitan regularly suffered from painful depression with a strong suicidal component. His surviving letters are filled with complaints of melancholy, dissatisfaction with himself, the inability to embody the beauty of nature to the full extent, and his personal disorder.

However, apparently, this sketch portrait by Nikolai Chekhov is associated with another disease. 25-year-old Levitan, who still did not have a stable income, was forced to take the commission he did not want — to paint a sketch of the Moskva River with barges frozen into the water near the Krasnokholmsky Bridge. Levitan did not like winter and did not paint much, but he needed money. In severe frost, in a thin coat and cold boots, Levitan worked in a piercing wind and developed inflammation of the periosteum (the biographers, however, do not specify the localization of the inflammation, they only say that the disease was difficult). Interesting thing: both in the hospital and in the hotel, where the recovering landscape painter was transported afterwards, his friends, the painters Nesterov and Stepanov, the architect Shekhtel, the Chekhov brothers, touchingly sat at his bedside, following a strict order. No wonder Ilya Ostroukhov said that Levitan was that rare person who had no enemies at all.

It seems that Nikolai Chekhov, who was on duty at Levitan’s bedside (by the way, he added a female figurine to Levitan’s Autumn Day. Sokolniki 6 years ago — see details), made this portrait. Chekhov was not an outstanding portrait painter. This image, as we can see, generalizes and idealizes Levitan’s features too much, but is curious as a document. As many as four years later, in 1889, Nikolai Chekhov would decease himself: at the age of 31 he would die of tuberculosis. Isaac with his heart disease would outlive his "consumptive" friend by 11 years.

Who is the painter? Nikolai Chekhov

Circumstances of the creation. This sketch was made by Nikolai Chekhov, Levitan’s classmate at the Moscow School of Painting, Sculpture and Architecture, the elder brother of the writer.

Levitan was often ill — the main reason for this was his orphan youth, at times homeless and at first, completely impoverished. He caught typhoid twice in his life. For the first time — at the age of 17, along with his father. The sympathetic neighbours then took away delirious Elyash (Ilya) and Isaac Levitan to different Moscow hospitals, and only Isaac returned from there — his father died. The second typhus, in the late 1890s, exacerbated his heart disease and brought his death closer, while he has not yet turned forty. Between those extreme cases, Levitan regularly suffered from painful depression with a strong suicidal component. His surviving letters are filled with complaints of melancholy, dissatisfaction with himself, the inability to embody the beauty of nature to the full extent, and his personal disorder.

However, apparently, this sketch portrait by Nikolai Chekhov is associated with another disease. 25-year-old Levitan, who still did not have a stable income, was forced to take the commission he did not want — to paint a sketch of the Moskva River with barges frozen into the water near the Krasnokholmsky Bridge. Levitan did not like winter and did not paint much, but he needed money. In severe frost, in a thin coat and cold boots, Levitan worked in a piercing wind and developed inflammation of the periosteum (the biographers, however, do not specify the localization of the inflammation, they only say that the disease was difficult). Interesting thing: both in the hospital and in the hotel, where the recovering landscape painter was transported afterwards, his friends, the painters Nesterov and Stepanov, the architect Shekhtel, the Chekhov brothers, touchingly sat at his bedside, following a strict order. No wonder Ilya Ostroukhov said that Levitan was that rare person who had no enemies at all.

It seems that Nikolai Chekhov, who was on duty at Levitan’s bedside (by the way, he added a female figurine to Levitan’s Autumn Day. Sokolniki 6 years ago — see details), made this portrait. Chekhov was not an outstanding portrait painter. This image, as we can see, generalizes and idealizes Levitan’s features too much, but is curious as a document. As many as four years later, in 1889, Nikolai Chekhov would decease himself: at the age of 31 he would die of tuberculosis. Isaac with his heart disease would outlive his "consumptive" friend by 11 years.

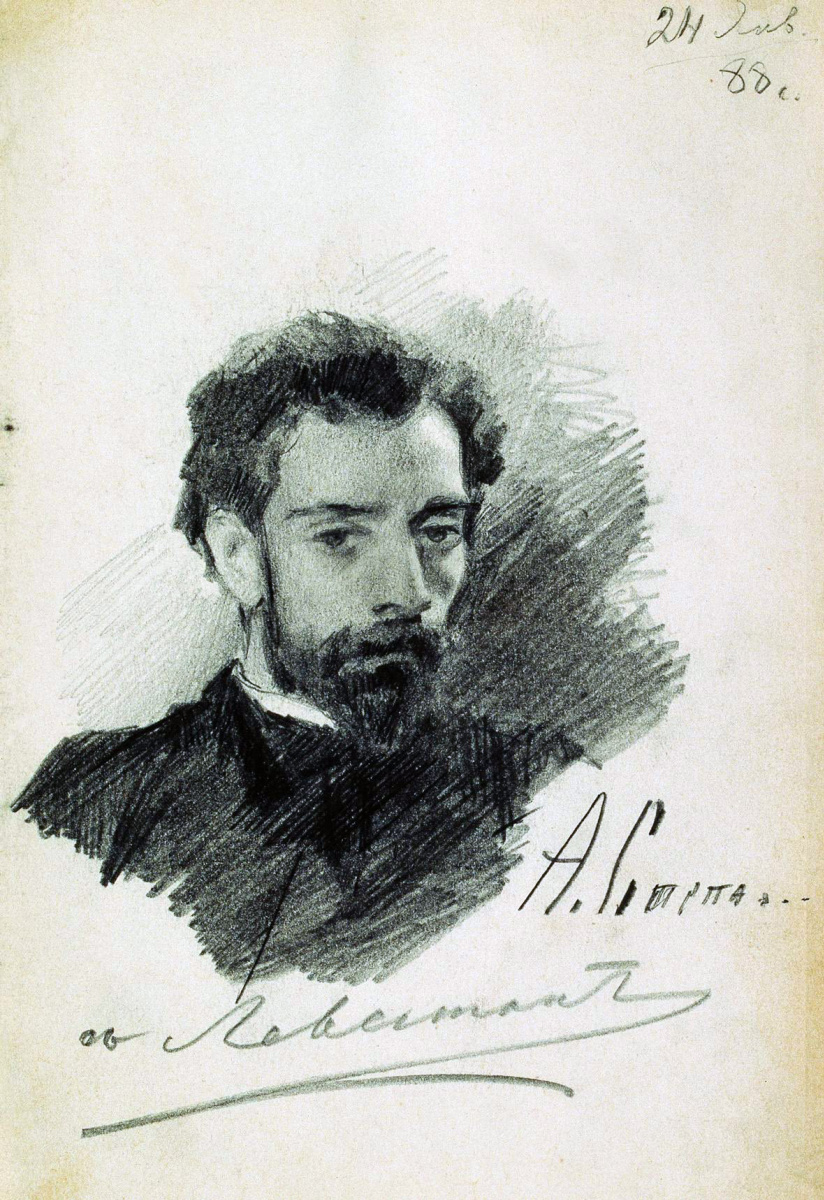

Portrait Of I. I. Levitan. Drawing signed by Levitan

1888, 21×13 cm

Role: thoughtful Levitan

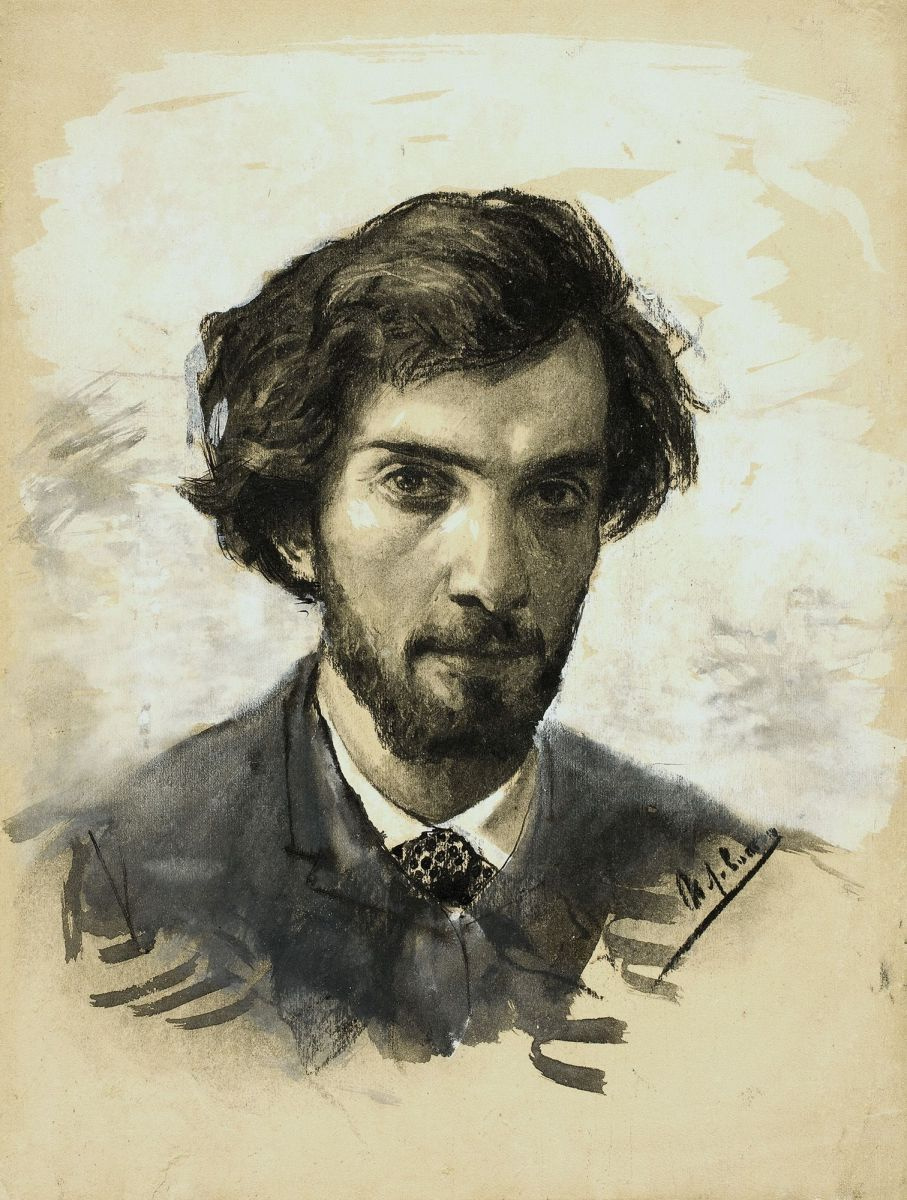

Who is the painter? Alexei Stepanov

Circumstances of the creation. This is another "friendly" portrait that was painted three years after the Chekhov’s sketch . It was made by Levitan’s fellow student, animal painter Alexei Stepanov. After graduating from college, both of them settled in sparsely furnished rooms of the Angliya hotel. The mocking Anton Chekhov joked that this would be their "English period of creativity". In Angliya, it was dark, smoky and terribly noisy. Friends had to open the curtains wider to let the light in, and to close and plug the doors with any suitable rag, so that intrusive extraneous noise would not interfere with their work. Both Levitan and Stepanov were not rich, both had a difficult childhood behind them, in a word, they had a lot in common. But what distinguished the two landscape painters was that Levitan always worked in the field of pure landscape , without deviating into the genre (for a long time, he remembered the "unnecessary woman", painted by Nikolai Chekhov — this is how their teacher Savrasov scolded after the exhibition), while Stepanov generously inhabited his landscapes with animals and people. He once "attached" a wolf into Levitan’s winter landscape. However, albeit he did it skillfully, but in vain: Levitan possessed a rare ability to make the landscape itself "speak" — he did not need people, animals, or even birds for this. The teacher Alexei Savrasov inspired Levitan: "You must learn to paint so that the lark on the canvas was not seen, but his singing heard."

Who is the painter? Alexei Stepanov

Circumstances of the creation. This is another "friendly" portrait that was painted three years after the Chekhov’s sketch . It was made by Levitan’s fellow student, animal painter Alexei Stepanov. After graduating from college, both of them settled in sparsely furnished rooms of the Angliya hotel. The mocking Anton Chekhov joked that this would be their "English period of creativity". In Angliya, it was dark, smoky and terribly noisy. Friends had to open the curtains wider to let the light in, and to close and plug the doors with any suitable rag, so that intrusive extraneous noise would not interfere with their work. Both Levitan and Stepanov were not rich, both had a difficult childhood behind them, in a word, they had a lot in common. But what distinguished the two landscape painters was that Levitan always worked in the field of pure landscape , without deviating into the genre (for a long time, he remembered the "unnecessary woman", painted by Nikolai Chekhov — this is how their teacher Savrasov scolded after the exhibition), while Stepanov generously inhabited his landscapes with animals and people. He once "attached" a wolf into Levitan’s winter landscape. However, albeit he did it skillfully, but in vain: Levitan possessed a rare ability to make the landscape itself "speak" — he did not need people, animals, or even birds for this. The teacher Alexei Savrasov inspired Levitan: "You must learn to paint so that the lark on the canvas was not seen, but his singing heard."

Portrait of Isaac Levitan

1891, 67×54 cm

Role: dandy Levitan

Who is the painter? Vasily Polenov

Circumstances of the creation. When in 1882, Alexei Savrasov, a talented man who was drinking more and more every year and did not hesitate to voice his unpleasant opinions, was quietly driven out from the Moscow School of Painting, Sculpture and Architecture, Vasily Polenov came to head his landscape class. Levitan was going to leave the school following his teacher: he spent eight years there, they did not award him big silver medal (because of their hostility to Savrasov and anti-Semitism that took place in the school), it was time to go on his own resources. But all of a sudden, Levitan stayed. Until recently, it seemed to him that no one, except Savrasov, was able to give him anything in the field of landscape, but suddenly it turned out that the new teacher Polenov was not only an interesting artist, but also a certified lawyer who perfectly knew several languages and travelled a lot around the world, he could teach Levitan a lot. Savrasov was not an outstanding colourist, whereas Polenov was. He knew how paints interacted, was interested in their chemistry, knew how to make the paint layer extremely durable and demanded pure festive colours from his students, and told the curious Levitan about the Barbizon school and the Impressionist artists. After meeting Polenov, there were fewer red and dark grey shades in Levitan’s painting, he began to indulge in a bright palette more boldly.

Levitan and Konstantin Korovin were Polenov’s favourites at the school. All three continued to communicate even after school. In company with Vasily Polenov, restless, yearning Levitan felt pacified. And in his darkest moments, Levitan sometimes turned to him in letters with a request to allow him to come and hunt in his estate. And Polenov often used Levitan as a model.

In this portrait by Polenov, Levitan is a little over thirty. He looks away and crosses his arms over his chest. Psychologist say that this gesture is a manifestation of the fact that the person is "closing himself". Levitan was just that — the door to his personal life or to the depths of his personality remained closed for almost everyone. External restraint and, as Alexander Benois wrote, "Oriental importance" were typical of him. Note the dandyish clothes on Levitan: a fine black frock coat, snow-white starch collar and cuffs, a large cufflink, a tie (Levitan knew how to wrap ties in some special way).

The dandy always lived in Levitan, and therefore in his youth, he was especially oppressed by his inevitable (and the only) checkered jacket with frayed elbows, smeared with paint, short trousers, a flashy red shirt, which Levitan had to wear for the whole summer, his last boots, which dried out after he painted sketches in the swamp. Even at his debut exhibition, where Tretyakov bought his painting for the first time, 19-year-old Levitan came in someone else’s clothes — a coat, hastily bought in a masquerade shop — and he was terribly embarrassed about this, as he was painfully neat by nature, loved beautiful clothes. Therefore, as soon as Levitan had money, he began to rush — he bought an expensive cane, for example, or shoes one number smaller, so that they fit the foot more gracefully. And his sister Theresa, if she managed to sell her brother’s sketch successfully, bought Levitan a thin shirt and cologne, as he liked, with the mignonette smell. By thirty years old, his financial situation had improved a little and Levitan pleased those around him with his somewhat picturesque elegance. The writer and translator Tatiana Shchepkina-Kupernik, for example, recalled his delightful velvet blouses, which set off his bright appearance.

Who is the painter? Vasily Polenov

Circumstances of the creation. When in 1882, Alexei Savrasov, a talented man who was drinking more and more every year and did not hesitate to voice his unpleasant opinions, was quietly driven out from the Moscow School of Painting, Sculpture and Architecture, Vasily Polenov came to head his landscape class. Levitan was going to leave the school following his teacher: he spent eight years there, they did not award him big silver medal (because of their hostility to Savrasov and anti-Semitism that took place in the school), it was time to go on his own resources. But all of a sudden, Levitan stayed. Until recently, it seemed to him that no one, except Savrasov, was able to give him anything in the field of landscape, but suddenly it turned out that the new teacher Polenov was not only an interesting artist, but also a certified lawyer who perfectly knew several languages and travelled a lot around the world, he could teach Levitan a lot. Savrasov was not an outstanding colourist, whereas Polenov was. He knew how paints interacted, was interested in their chemistry, knew how to make the paint layer extremely durable and demanded pure festive colours from his students, and told the curious Levitan about the Barbizon school and the Impressionist artists. After meeting Polenov, there were fewer red and dark grey shades in Levitan’s painting, he began to indulge in a bright palette more boldly.

Levitan and Konstantin Korovin were Polenov’s favourites at the school. All three continued to communicate even after school. In company with Vasily Polenov, restless, yearning Levitan felt pacified. And in his darkest moments, Levitan sometimes turned to him in letters with a request to allow him to come and hunt in his estate. And Polenov often used Levitan as a model.

In this portrait by Polenov, Levitan is a little over thirty. He looks away and crosses his arms over his chest. Psychologist say that this gesture is a manifestation of the fact that the person is "closing himself". Levitan was just that — the door to his personal life or to the depths of his personality remained closed for almost everyone. External restraint and, as Alexander Benois wrote, "Oriental importance" were typical of him. Note the dandyish clothes on Levitan: a fine black frock coat, snow-white starch collar and cuffs, a large cufflink, a tie (Levitan knew how to wrap ties in some special way).

The dandy always lived in Levitan, and therefore in his youth, he was especially oppressed by his inevitable (and the only) checkered jacket with frayed elbows, smeared with paint, short trousers, a flashy red shirt, which Levitan had to wear for the whole summer, his last boots, which dried out after he painted sketches in the swamp. Even at his debut exhibition, where Tretyakov bought his painting for the first time, 19-year-old Levitan came in someone else’s clothes — a coat, hastily bought in a masquerade shop — and he was terribly embarrassed about this, as he was painfully neat by nature, loved beautiful clothes. Therefore, as soon as Levitan had money, he began to rush — he bought an expensive cane, for example, or shoes one number smaller, so that they fit the foot more gracefully. And his sister Theresa, if she managed to sell her brother’s sketch successfully, bought Levitan a thin shirt and cologne, as he liked, with the mignonette smell. By thirty years old, his financial situation had improved a little and Levitan pleased those around him with his somewhat picturesque elegance. The writer and translator Tatiana Shchepkina-Kupernik, for example, recalled his delightful velvet blouses, which set off his bright appearance.

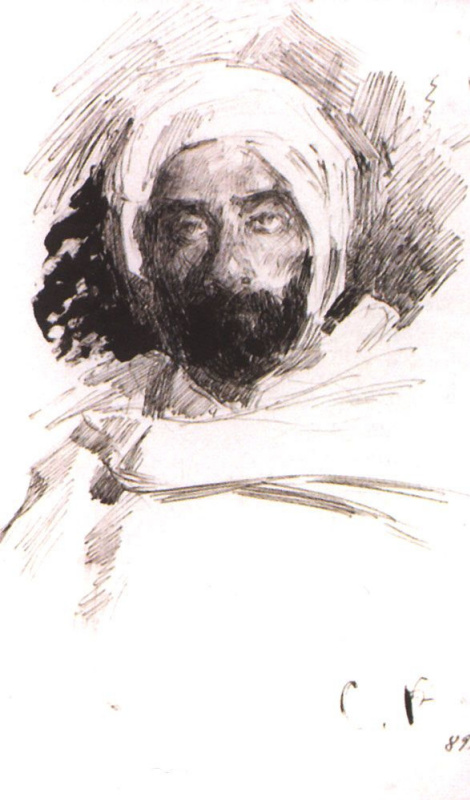

Role: Levitan, the oriental sage

Who is the painter? Vasily Polenov

Circumstances of the creation. Polenov worked on this piece for many years. As he himself, his parents and friends believed, it should have become his main product — a huge picture of the life of Christ (now we know this work under the title "Christ and the Sinner"). The artist was interested in the historical Christ, not His perfectly beautiful image the painting of the Renaissance and the Baroque presented to mankind, but the way He could be in reality. Polenov made countless sketches and preliminary works for Christ and the Sinner. His favourite disciples, Korovin and Levitan, posed for Jesus, both of their profile portraits have survived. But if we were to set the goal of complete plausibility, we had to admit that the Jew (and also the grandson of a rabbi) Levitan looked like much more authentic and organic model for the figure of Christ than Korovin. In the final version of the Polenov’s painting (and in his other paintings of the Gospel series), Levitan’s appearance is obvious.

Interestingly, initially in Christ and the Sinner, Levitan, the Polenov’s model for the Saviour, had to be wearing a headdress, just as in this sketch — it was impossible to do otherwise under the scorching Palestinian sun, and it is not for nothing that all other characters are depicted with their heads covered. But "Christ in the cap" greatly outraged Polenov’s mother, a domineering woman, a little absurd. She had a huge influence on her son: this was against the pictorial tradition, neither Raphael nor Rubens allowed themselves to paint this way! And at the last moment, Polenov gave up and left Levitan without his headdress in the big picture.

Who is the painter? Vasily Polenov

Circumstances of the creation. Polenov worked on this piece for many years. As he himself, his parents and friends believed, it should have become his main product — a huge picture of the life of Christ (now we know this work under the title "Christ and the Sinner"). The artist was interested in the historical Christ, not His perfectly beautiful image the painting of the Renaissance and the Baroque presented to mankind, but the way He could be in reality. Polenov made countless sketches and preliminary works for Christ and the Sinner. His favourite disciples, Korovin and Levitan, posed for Jesus, both of their profile portraits have survived. But if we were to set the goal of complete plausibility, we had to admit that the Jew (and also the grandson of a rabbi) Levitan looked like much more authentic and organic model for the figure of Christ than Korovin. In the final version of the Polenov’s painting (and in his other paintings of the Gospel series), Levitan’s appearance is obvious.

Interestingly, initially in Christ and the Sinner, Levitan, the Polenov’s model for the Saviour, had to be wearing a headdress, just as in this sketch — it was impossible to do otherwise under the scorching Palestinian sun, and it is not for nothing that all other characters are depicted with their heads covered. But "Christ in the cap" greatly outraged Polenov’s mother, a domineering woman, a little absurd. She had a huge influence on her son: this was against the pictorial tradition, neither Raphael nor Rubens allowed themselves to paint this way! And at the last moment, Polenov gave up and left Levitan without his headdress in the big picture.

Christ and the sinner (Who is without a sin?)

1888, 325×611 cm

Role: Levitan the Bedouin

Who is the painter? Vasily Polenov, Sergey Vinogradov

Circumstances of the creation. Since 1884, Vasily Polenov has begun an interesting tradition of working together with students and friends right at home: on Thursdays, the Polenovs held "Drawing Thursdays", and on Sundays, "Watercolour Mornings". Young people were frequent guests of such meetings: Konstantin and Sergey Korovin, Ilya Ostroukhov, Sergey Vinogradov, Isaac Levitan, Mikhail Nesterov, Leonid Pasternak, Elena Polenova and others.

Who was more likely to become a model? Undoubtedly — the picturesque Levitan. While preparing for his biblical paintings, Vasily Polenov travelled to Palestine and from his trips, he brought oriental clothes that could be useful to him in his work. At one of the creative meetings, Levitan was dressed up in a Bedouin costume, and the rest of the visitors of the "Drawing Thursday", including the owner of the house, surrounded the reincarnated landscape painter, and concentrated on their paper and pencils.

Levitan was very good in the image of a Bedouin, the artist seemed to project a mysterious "call of the ancestors". Levitan’s friend, Tatyana Schepkina-Kupernik described him as follows: "A very interesting matte-pale face, completely from a Velázquez portrait, slightly curly dark hair, an expansive forehead, velvet eyes, a pointed beard: the Semitic type in its noblest expression, the Arabic-Spanish".

In the summer of 1885 and 1886, Levitan continued his reincarnations as a Bedouin, but with a different goal. He and Anton Chekhov went to the Babkino estate near Moscow, and staged hilarious performances, dressing up as Bedouins. First, they wrapped themselves in sheets and Levitan, to the laughter of those around him, taught Chekhov how to "walk like a Bedouin". Then the actual action began. Chekhov the Bedouin took a gun, hid in the bushes, and Levitan the Bedouin, saddled a donkey (which the owners of the estate kept for their children), slowly circled the meadow for a long time, as though choosing a place for "prayer". Then Levitan dismounted from the donkey and began to "perform Namaz", making loud mournful throat sounds. Meanwhile, from the bushes, a Bedouin assassin was slowly crawling towards him on his belly and taking aim. On the most shrill and harsh note, the Bedouin’s prayer was interrupted by Chekhov’s well-aimed shot. The people around were not just laughing — they were rolling on the grass and split their sides. Levitan fell on his back, his "corpse" was loaded onto a stretcher, and the next act of the comedy began — a funny funeral. The "follies" in Babkino remained the happiest memories for Levitan.

Who is the painter? Vasily Polenov, Sergey Vinogradov

Circumstances of the creation. Since 1884, Vasily Polenov has begun an interesting tradition of working together with students and friends right at home: on Thursdays, the Polenovs held "Drawing Thursdays", and on Sundays, "Watercolour Mornings". Young people were frequent guests of such meetings: Konstantin and Sergey Korovin, Ilya Ostroukhov, Sergey Vinogradov, Isaac Levitan, Mikhail Nesterov, Leonid Pasternak, Elena Polenova and others.

Who was more likely to become a model? Undoubtedly — the picturesque Levitan. While preparing for his biblical paintings, Vasily Polenov travelled to Palestine and from his trips, he brought oriental clothes that could be useful to him in his work. At one of the creative meetings, Levitan was dressed up in a Bedouin costume, and the rest of the visitors of the "Drawing Thursday", including the owner of the house, surrounded the reincarnated landscape painter, and concentrated on their paper and pencils.

Levitan was very good in the image of a Bedouin, the artist seemed to project a mysterious "call of the ancestors". Levitan’s friend, Tatyana Schepkina-Kupernik described him as follows: "A very interesting matte-pale face, completely from a Velázquez portrait, slightly curly dark hair, an expansive forehead, velvet eyes, a pointed beard: the Semitic type in its noblest expression, the Arabic-Spanish".

In the summer of 1885 and 1886, Levitan continued his reincarnations as a Bedouin, but with a different goal. He and Anton Chekhov went to the Babkino estate near Moscow, and staged hilarious performances, dressing up as Bedouins. First, they wrapped themselves in sheets and Levitan, to the laughter of those around him, taught Chekhov how to "walk like a Bedouin". Then the actual action began. Chekhov the Bedouin took a gun, hid in the bushes, and Levitan the Bedouin, saddled a donkey (which the owners of the estate kept for their children), slowly circled the meadow for a long time, as though choosing a place for "prayer". Then Levitan dismounted from the donkey and began to "perform Namaz", making loud mournful throat sounds. Meanwhile, from the bushes, a Bedouin assassin was slowly crawling towards him on his belly and taking aim. On the most shrill and harsh note, the Bedouin’s prayer was interrupted by Chekhov’s well-aimed shot. The people around were not just laughing — they were rolling on the grass and split their sides. Levitan fell on his back, his "corpse" was loaded onto a stretcher, and the next act of the comedy began — a funny funeral. The "follies" in Babkino remained the happiest memories for Levitan.

Portrait of the artist Isaac Levitan

1893, 82×86 cm

Role: Levitan both the celebrity and the outcast

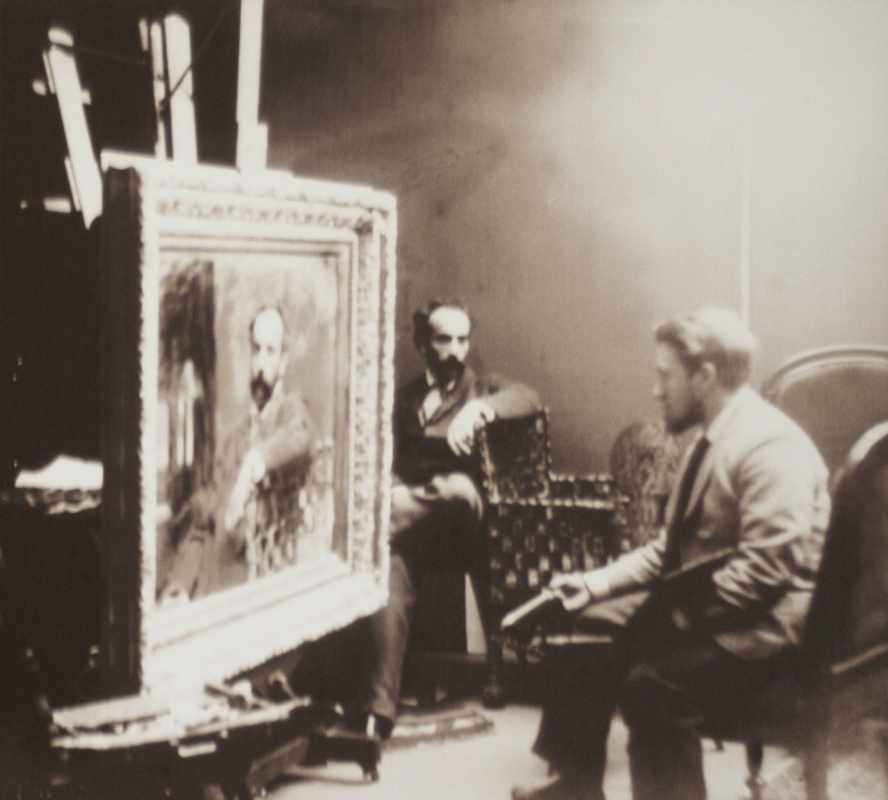

Who is the painter? Vladimir Serov.

Circumstances of the creation. In 1892, Grand Duke Sergei Alexandrovich became the Governor-General of Moscow, and one of his first decisions was to evict all Jewish artisans from the city. Zealous officials, fueling the hysteria of anti-Semitism, handed Levitan and his family an order to leave Moscow. This was already the case more than ten years ago, when the Narodnaya Volya activists attempted to assassinate the tsar, and the Jews were appointed whipping boys; however, at that time the expelled from Moscow Levitan was an unknown 19-year-old student, there was no one to intercede for him. And now an artist with all-Russian glory, who had received first fame outside the country as well, was expelled from Moscow.

Influential persons, including Tretyakov, whose gallery already contained a lot of Levitan’s masterpieces, fought for Levitan, and by the end of the year, Levitan nevertheless returned to Moscow, to his studio in Tryokhsvyatitelsky lane, provided to him by an admirer of his work, industrialist and philanthropist Sergei Morozov. The artist Valentin Serov came to the second floor of this house, climbing a twisted staircase, to paint a portrait of Levitan.

The unpleasant story of Levitan’s expulsion was known to Serov, a man of great nobility and exceptional moral scrupulousness. The fact that he conceived to paint a portrait of Levitan at this difficult time for the landscape painter can be regarded as "an act of moral support, a desire to protect a colleague from the unfair actions of the Moscow authorities," writes Serov’s biographer Valentin Kudrya. "Serov was finishing the portrait, realizing that he, perhaps, did well to reflect the inner world of Levitan, his inherent sadness and melancholy. Hands were usually difficult for him, but this time the model’s artistry was also emphasized by his carelessly lowered hand with thin, expressive fingers."

Who is the painter? Vladimir Serov.

Circumstances of the creation. In 1892, Grand Duke Sergei Alexandrovich became the Governor-General of Moscow, and one of his first decisions was to evict all Jewish artisans from the city. Zealous officials, fueling the hysteria of anti-Semitism, handed Levitan and his family an order to leave Moscow. This was already the case more than ten years ago, when the Narodnaya Volya activists attempted to assassinate the tsar, and the Jews were appointed whipping boys; however, at that time the expelled from Moscow Levitan was an unknown 19-year-old student, there was no one to intercede for him. And now an artist with all-Russian glory, who had received first fame outside the country as well, was expelled from Moscow.

Influential persons, including Tretyakov, whose gallery already contained a lot of Levitan’s masterpieces, fought for Levitan, and by the end of the year, Levitan nevertheless returned to Moscow, to his studio in Tryokhsvyatitelsky lane, provided to him by an admirer of his work, industrialist and philanthropist Sergei Morozov. The artist Valentin Serov came to the second floor of this house, climbing a twisted staircase, to paint a portrait of Levitan.

The unpleasant story of Levitan’s expulsion was known to Serov, a man of great nobility and exceptional moral scrupulousness. The fact that he conceived to paint a portrait of Levitan at this difficult time for the landscape painter can be regarded as "an act of moral support, a desire to protect a colleague from the unfair actions of the Moscow authorities," writes Serov’s biographer Valentin Kudrya. "Serov was finishing the portrait, realizing that he, perhaps, did well to reflect the inner world of Levitan, his inherent sadness and melancholy. Hands were usually difficult for him, but this time the model’s artistry was also emphasized by his carelessly lowered hand with thin, expressive fingers."

Isaac Levitan poses for Valentin Serov in his studio in Tryokhsvyatitelsky lane. Early 1890s.

Photo: commons.wikimedia.org

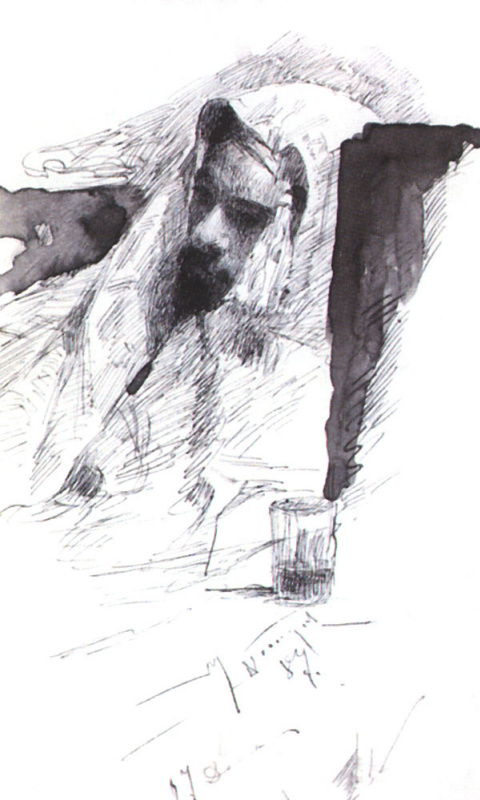

Self-portrait

1890-th

, 39×58 cm

Role: Man in the face of death

Who is the painter? Isaac Levitan

Circumstances of the creation. His last self-portrait was painted by Levitan about a year before his death, in 1899. By this time, Levitan already knew that he was doomed.

In March 1897, still hoping that his heart ailment could be reversible and non-fatal, he asked his friend Anton Chekhov for a consultation. Levitan’s letter of 8 February 1897 was written in a lyrical, familiarly mocking manner, usual for their correspondence:

"A short while ago, I almost popped off again and, having recovered a little, now I am thinking of arranging a consultation at my place, headed by Ostroumov, and no later than in a few days. Shouldn’t you stop by Levitan as only a decent person, in general, and, by the way, advise how to arrange all this. Do you hear, adder? Your Shmul."

Chekhov arrived with his stethoscope, listened to his heart carefully, tapped him, joked as usual, tried to cheer Levitan up. But soon he said to architect Shekhtel: "It's bad. His heart does not beat, it blows. Instead of a knock-knock sound, a pff-knock is heard. Medicine calls it "noise with the first time".

Realizing the real danger Levitan was not going to give up, though earlier he had tried to commit suicide at least three times. He now taught at the Moscow School of Painting, Sculpture and Architecture, in the same class where he once met Savrasov, his students were to make their debut at the Travelling Exhibition, and Levitan worried about them more than about himself. "With sunken eyes, bald ahead of time, with a tortured face, with a stick in his hand, resting every two steps," Ivan Evdokimov described Levitan in his last year of life, "he went to St. Petersburg for the opening day. He was like this in everything, always — selflessly, without looking back."

In December 1899 (the resulting self-portrait had already been completed by that time), Levitan left for Yalta, to Chekhov, to meet the new 1900, his last year. Climbing the mountain together with Chekhov’s sister Masha, whom he made a marriage proposal many years ago, Levitan said: "I really need to go there, higher, where the air is lighter, where it is good to breathe, Marie! I don’t want to die so much. It is scary to die… And my heart, it hurts so much…"

Who is the painter? Isaac Levitan

Circumstances of the creation. His last self-portrait was painted by Levitan about a year before his death, in 1899. By this time, Levitan already knew that he was doomed.

In March 1897, still hoping that his heart ailment could be reversible and non-fatal, he asked his friend Anton Chekhov for a consultation. Levitan’s letter of 8 February 1897 was written in a lyrical, familiarly mocking manner, usual for their correspondence:

"A short while ago, I almost popped off again and, having recovered a little, now I am thinking of arranging a consultation at my place, headed by Ostroumov, and no later than in a few days. Shouldn’t you stop by Levitan as only a decent person, in general, and, by the way, advise how to arrange all this. Do you hear, adder? Your Shmul."

Chekhov arrived with his stethoscope, listened to his heart carefully, tapped him, joked as usual, tried to cheer Levitan up. But soon he said to architect Shekhtel: "It's bad. His heart does not beat, it blows. Instead of a knock-knock sound, a pff-knock is heard. Medicine calls it "noise with the first time".

Realizing the real danger Levitan was not going to give up, though earlier he had tried to commit suicide at least three times. He now taught at the Moscow School of Painting, Sculpture and Architecture, in the same class where he once met Savrasov, his students were to make their debut at the Travelling Exhibition, and Levitan worried about them more than about himself. "With sunken eyes, bald ahead of time, with a tortured face, with a stick in his hand, resting every two steps," Ivan Evdokimov described Levitan in his last year of life, "he went to St. Petersburg for the opening day. He was like this in everything, always — selflessly, without looking back."

In December 1899 (the resulting self-portrait had already been completed by that time), Levitan left for Yalta, to Chekhov, to meet the new 1900, his last year. Climbing the mountain together with Chekhov’s sister Masha, whom he made a marriage proposal many years ago, Levitan said: "I really need to go there, higher, where the air is lighter, where it is good to breathe, Marie! I don’t want to die so much. It is scary to die… And my heart, it hurts so much…"

Portrait of Isaac Levitan

1900-th

, 100×64 cm

Role: Levitan the ghost

Who is the painter? Vladimir Serov.

Circumstances of the creation. Valentin Serov painted this pastel portrait when Levitan had been dead for about a year. The previous Serov’s portrait had a good press and deserved a lot of praise from critics, the public, and — which happens infrequently — the model herself. Artist Vladimir Sokolov, one of Levitan’s students, reported the words of his teacher: "It is an amazing thing! Serov is an amazing artist. I am sure that my portrait by him will later be in the Tretyakov Gallery." However, surprisingly, the work of the perfectionist Serov did not bring satisfaction to himself, he did not consider Levitan’s portrait successful, he thought that he should have been portrayed differently.

In 1901, a student exhibition in memory of Levitan was planned. For Serov, this became an occasion to propose another solution for the image of Levitan, to paint him in a different, new way. This time he worked with pastels and depicted Levitan in a hat and coat, in a three-quarter turn, choosing a slightly lower angle. The artist Boris Lipkin recalled that Serov was interested in his opinion: "How is the portrait?" Lipkin, who knew Levitan well during his lifetime, did not dare to lie out of respect for Serov. "The portrait doesn’t seem very similar to me," he said. Serov immediately agreed: "Yes, I cannot paint without nature. The hat and coat are those of Levitan, but the body is not. The head is a fail, I painted it from Adolf and photographs, it didn’t work, I don’t know how to do without nature…"

Adolf was the name of Levitan’s brother, also an artist, who entered the Moscow School of Painting, Sculpture and Architecture "to study as an artist" a year earlier than Isaac, and survived the famous relative by 33 years.

Who is the painter? Vladimir Serov.

Circumstances of the creation. Valentin Serov painted this pastel portrait when Levitan had been dead for about a year. The previous Serov’s portrait had a good press and deserved a lot of praise from critics, the public, and — which happens infrequently — the model herself. Artist Vladimir Sokolov, one of Levitan’s students, reported the words of his teacher: "It is an amazing thing! Serov is an amazing artist. I am sure that my portrait by him will later be in the Tretyakov Gallery." However, surprisingly, the work of the perfectionist Serov did not bring satisfaction to himself, he did not consider Levitan’s portrait successful, he thought that he should have been portrayed differently.

In 1901, a student exhibition in memory of Levitan was planned. For Serov, this became an occasion to propose another solution for the image of Levitan, to paint him in a different, new way. This time he worked with pastels and depicted Levitan in a hat and coat, in a three-quarter turn, choosing a slightly lower angle. The artist Boris Lipkin recalled that Serov was interested in his opinion: "How is the portrait?" Lipkin, who knew Levitan well during his lifetime, did not dare to lie out of respect for Serov. "The portrait doesn’t seem very similar to me," he said. Serov immediately agreed: "Yes, I cannot paint without nature. The hat and coat are those of Levitan, but the body is not. The head is a fail, I painted it from Adolf and photographs, it didn’t work, I don’t know how to do without nature…"

Adolf was the name of Levitan’s brother, also an artist, who entered the Moscow School of Painting, Sculpture and Architecture "to study as an artist" a year earlier than Isaac, and survived the famous relative by 33 years.

Role: Levitan the brother

Who is the painter? Adolf Levitan

Circumstances of the creation. Few people remembered Isaac Levitan beardless, that young and not resembling his own "canonical" portraits. Except his friend and peer Mikhail Nesterov, who wrote: "I recognized Levitan in this young man, I was like him then. An unusually handsome, graceful Jewish boy looked like those Italian boys who met the Forestieri on the old Santa Lucia of Naples or in the squares of Florence, somewhere near Santa Maria Novella, with a scarlet flower in their curly hair. Young Levitan also attracted attention by the fact that he was already known in school for his talent." Another man who remembered Isaac like that and, perhaps, did not want to know him as the man he would become later, was his brother and the author of this amazing portrait, Adolf Levitan.

The Levitans' family history is confusing and strange. It is quite comprehensible why Isaac did not want to tell anything about his childhood so stubbornly, and ordered to burn all his correspondence after death. His brother Abel Leib, who took the name Adolf on his own initiative, did not leave any memories, although he survived Isaac by 33 years. The well-established version of their biography says: in the family of Lithuanian Sephardi Jews Elyash and Basia Levitans, there were two sons, Abel and Isaac, and two daughters, Theresa and Emma. When the family moved to Moscow, the more capable Abel began to study painting, and a year later, in the footsteps of his brother, 13-year-old Isaac wrote a petition to take him to the school. Both made progress and, due to their extreme poverty, received financial assistance from the school sometimes. School acquaintances spoke of them in the plural: the Levitans. Everyone recognized that the brothers were very similar.

Orphaned, the Levitans shared adversity, sometimes were hungry, unsuccessfully tried to paint something commercially profitable together (Abel was responsible for the figures, Isaac — for the landscape). In the late 1870s, together with other Jews, they were expelled from Moscow to Saltykovka for the first time. On 30 May 1879, Abel painted the portrait of Isaac there. There is a certain fraternal tenderness in it. For both, everything was still ahead, and Abel, of course, did not yet suspect that only one Levitan would remain in the history of art, Isaac.

We do not know much about Abel, we don’t even have his photographs. Like his brother, he participated in exhibitions, received small silver medals, printed his drawings in humorous magazines, painted something. But Adolf, unlike Isaac, was not accepted into the Society of Travelling Art Exhibitions. And unlike Isaac, he did not manage to go abroad, although Adolf addressed a written request to Tretyakov to assist him. After Isaac’s death, Abel, fulfilling his dying will, burned all the letters and became the administrator of his legacy. They loved Isaac in the artistic environment, however were wary and even hostile towards Adolf, for which there are several epistolary evidences. A few years later, Abel-Adolph left for Yalta, ran a small art studio there, and lived as a recluse. Almost nothing is known about his work, as well as about his personality. Whether Abel considered his more talented brother Cain in the depths of his soul, it is difficult to judge.

Metrics newly discovered in 2010 by Mikhail Rogov indicate that Isaac could not have been born into the family of Adolf’s parents, Elyashiv (Ilya) and Basia Levitan. According to the documents, they had two children: daughter Mikhle and son Abel Leib, who was born on 9 January 1861. And the son Itzik Leib (probably, Isaac) was born on 3 October 1860 into the family of Elyashiv’s brother Khatskel and his wife Dobra. Mikhail Rogov suggests that Isaac was taken from the impoverished Khatskel’s family to be brought up in the more prosperous family of Elyashiv and Basia as a "poor relative".

Considering this version, the long-known, but not completely understandable declaration of Maria Chekhova gets a new meaning. She claimed that Isaac Levitan "never said anything about his relatives or childhood. It turned out as if he had neither a father nor a mother at all. Sometimes it even seemed to me that he wanted to forget about their existence… ".

Who is the painter? Adolf Levitan

Circumstances of the creation. Few people remembered Isaac Levitan beardless, that young and not resembling his own "canonical" portraits. Except his friend and peer Mikhail Nesterov, who wrote: "I recognized Levitan in this young man, I was like him then. An unusually handsome, graceful Jewish boy looked like those Italian boys who met the Forestieri on the old Santa Lucia of Naples or in the squares of Florence, somewhere near Santa Maria Novella, with a scarlet flower in their curly hair. Young Levitan also attracted attention by the fact that he was already known in school for his talent." Another man who remembered Isaac like that and, perhaps, did not want to know him as the man he would become later, was his brother and the author of this amazing portrait, Adolf Levitan.

The Levitans' family history is confusing and strange. It is quite comprehensible why Isaac did not want to tell anything about his childhood so stubbornly, and ordered to burn all his correspondence after death. His brother Abel Leib, who took the name Adolf on his own initiative, did not leave any memories, although he survived Isaac by 33 years. The well-established version of their biography says: in the family of Lithuanian Sephardi Jews Elyash and Basia Levitans, there were two sons, Abel and Isaac, and two daughters, Theresa and Emma. When the family moved to Moscow, the more capable Abel began to study painting, and a year later, in the footsteps of his brother, 13-year-old Isaac wrote a petition to take him to the school. Both made progress and, due to their extreme poverty, received financial assistance from the school sometimes. School acquaintances spoke of them in the plural: the Levitans. Everyone recognized that the brothers were very similar.

Orphaned, the Levitans shared adversity, sometimes were hungry, unsuccessfully tried to paint something commercially profitable together (Abel was responsible for the figures, Isaac — for the landscape). In the late 1870s, together with other Jews, they were expelled from Moscow to Saltykovka for the first time. On 30 May 1879, Abel painted the portrait of Isaac there. There is a certain fraternal tenderness in it. For both, everything was still ahead, and Abel, of course, did not yet suspect that only one Levitan would remain in the history of art, Isaac.

We do not know much about Abel, we don’t even have his photographs. Like his brother, he participated in exhibitions, received small silver medals, printed his drawings in humorous magazines, painted something. But Adolf, unlike Isaac, was not accepted into the Society of Travelling Art Exhibitions. And unlike Isaac, he did not manage to go abroad, although Adolf addressed a written request to Tretyakov to assist him. After Isaac’s death, Abel, fulfilling his dying will, burned all the letters and became the administrator of his legacy. They loved Isaac in the artistic environment, however were wary and even hostile towards Adolf, for which there are several epistolary evidences. A few years later, Abel-Adolph left for Yalta, ran a small art studio there, and lived as a recluse. Almost nothing is known about his work, as well as about his personality. Whether Abel considered his more talented brother Cain in the depths of his soul, it is difficult to judge.

Metrics newly discovered in 2010 by Mikhail Rogov indicate that Isaac could not have been born into the family of Adolf’s parents, Elyashiv (Ilya) and Basia Levitan. According to the documents, they had two children: daughter Mikhle and son Abel Leib, who was born on 9 January 1861. And the son Itzik Leib (probably, Isaac) was born on 3 October 1860 into the family of Elyashiv’s brother Khatskel and his wife Dobra. Mikhail Rogov suggests that Isaac was taken from the impoverished Khatskel’s family to be brought up in the more prosperous family of Elyashiv and Basia as a "poor relative".

Considering this version, the long-known, but not completely understandable declaration of Maria Chekhova gets a new meaning. She claimed that Isaac Levitan "never said anything about his relatives or childhood. It turned out as if he had neither a father nor a mother at all. Sometimes it even seemed to me that he wanted to forget about their existence… ".

Written by Anna Vcherashniaya