Arnold Houbraken, a Dutch artist of the XVII century, engraver and historiographer

"He was a highly industrious, tireless individual. Success provided him with large sums of money, and his house in Amsterdam was full of many children who were given to him for teaching. Each of them paid him one hundred guldens per year, so Rembrandt made between 2,000 and 2,500 guilders annually from his tuition fees and the sale of student work. This sum did not include the sales of his own paintings and prints."

Joachim von Sandrart, a German artist and art historian of the 17th century, sometimes called the "German Vasari".

Differences in the workshops of Rubens and Rembrandt

Rembrandt’s method differed significantly from the style of teaching adopted, for example, in the workshop of his older colleague Rubens. Rubens recruited pupils for his workshop in Antwerp in order for them to help the artist in his work. A great Flemish, popular not only in Flanders, but throughout Europe, received a huge number of commissions from everywhere, and the workshop was necessary for him, above all, to cope with this endless stream. The structure of the work was usually as following: Rubens sketched and corrected the painting at the very end, and his "staff" was given the whole main stage. To increase the speed and efficiency of work, Rubens shared the duties: some of the pupils painted the background, others were focused on details — they worked on foliage or clothing, the master himself corrected the whole work and execute the most "important" parts — hands and faces.The work of Rembrandt’s workshop was arranged in a different way. There, the pupil was not the "staff" of a master. He rather participated in the art discussion initiated by the master of the workshop, rather than making "technical" works under the recognizable "label". Rembrandt offered the subjects to his pupils — sometimes those that interested him (as a rule, the Old Testament themes), sometimes completely new ones, for which there was no established canon in fine art, so the student had to develop a theme independently, think about its composition, add unordinary details or new characters.

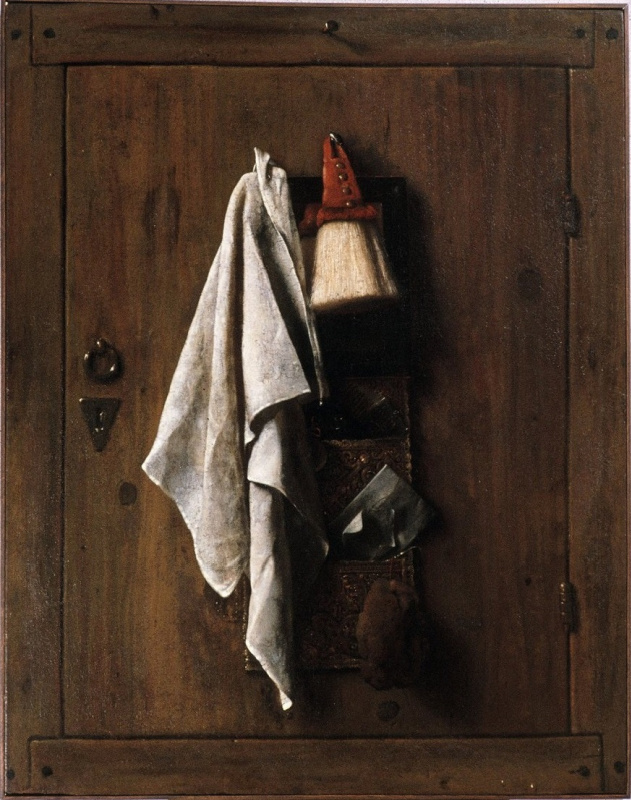

Actually, the "closets" were needed for the same purpose — to individualize the search, to reduce mutual influence, to awaken and develop independent artistic thinking.

At different times in the workshop of Rembrandt Gerrit Dou, Samuel van Hoogstraten, Willem Drost, Aert de Gelder and others were taught by Rembrandt.

Everyday life of Rembrandt's workshop

Rembrandt realized perfectly well that his tasks were complicated. That’s why he followed the rule never to take beginners. There were three types of pupil in Rembrandt’s workshop. Firstly, there were the pupils aged between twelve and fourteen, the boys who wanted to become painters. In the second group were the assistants, who after training with Rembrandt remained in the workshop and helped with instruction and production. They were painters who made their own paintings in the style of the master, some of which are considered to be genuine Rembrandts to this day. Finally, there were the ‘amateurs', who took drawing and painting lessons as part of a good upbringing and did not need to make a living from painting.Teaching was a lucrative business; Rembrandt received around a hundred guilders tuition fees a year for each pupil. It was an additional criterion for selection of random people. The memoirists, who are not very friendly to Rembrandt, after many years would calculate the "profits" of the artist and display him as a grumbling miser, "an eccentric who despised everyone" and tell how the students joked drawing coins on the floor, indistinguishable from the real ones, and Rembrandt leaned down to put them.

Although the majority of Rembrandt’s pupils already had the concept of painting by the time they came to the workshop, one does not need to think that they were spared the routine duties of the apprentices. In the same way as in the workshops of hundreds and thousands of other artists, Rembrandt’s pupils were rubbing the pigments and filtering the oil, cutting the canvases and pulling them onto the stretcher, wiping the dust from the windows to let in more light, preparing props and moving heavy armchairs for the Amsterdam burghers, who came to pose for portraits.

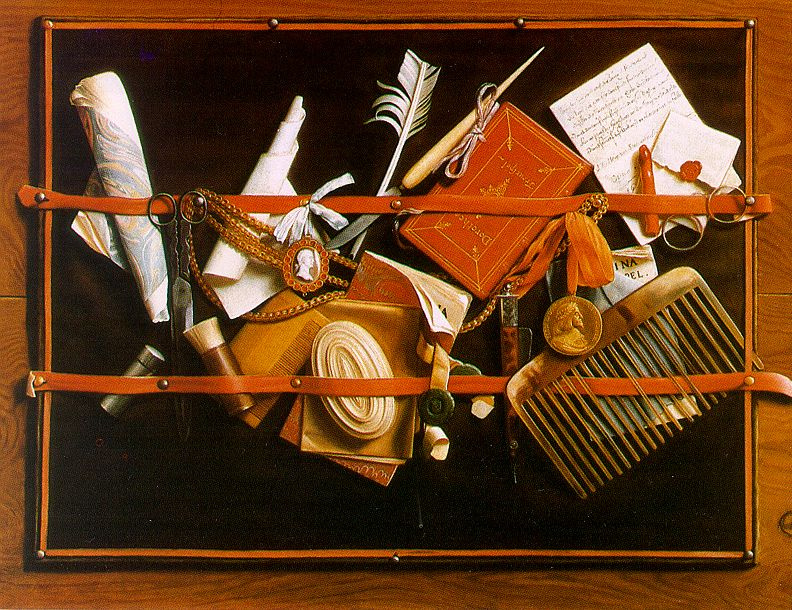

The conditions in the workshop of Rembrandt contributed pupils to the work: the plaster busts of the great men of antiquity, that Rembrandt collected, looked at them from the shelves, the walls were covered with other objects of his personal collection of rarities: weapons of different times and peoples, glistening metal helmets, robes of expensive fabrics — all this could be useful for paintings on historical themes. There were also large folders with drawings and etchings of Rembrandt, to which the students had unlimited access. In addition, the most valuable collections of drawings of Renaissance artists were to their services, from Durer to Raphael, which Rembrandt collected and for which spared no expense in his best times.

However, no matter how democratic Rembrandt’s workshop was compared to the studio of his more successful (from the career and public points of view) colleague Rubens, it’s hard to deny the obvious: Anthony van Dyck came out of the studio of the latter, and Rembrandt did not have such significant followers.

"Among the pupils of Rembrandt there were a lot of mediocrities and even complete lack of talent, which today is reverently venerated and misappropriated praised", argues the author of the book "Rembrandt's Eyes" Simon Schama. "But even in cases when their performance level speaks of the famous craftsmanship, none of the pupils, colleagues, assistants of Rembrandt has ever achieved the originality of the idea that the "The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp"," The Shipbuilder and his Wife": Jan Rijcksen and Griet Jans"or "The Mennonite Preacher Anslo and his Wife" have. The misfortune of the most zealous students was that if only they (sometimes easily, sometimes in agony) instilled Rembrandt’s technique to their natural abilities, as their teacher had already radically revised the foundations of his own style. By the beginning of the 1640s, when a new cohort of pupils had appeared in his studio, including some of his most talented followers: Carel Fabritius and his brother Barent, Samuel van Hoogstraten, Rembrandt gradually abandoned the Baroque style in the paintings on historical themes, thus his bright, rich color and dynamism, to which he gravitated throughout the previous decade (like "Belshazzar's Feast" and "The Blinding of Samson"), were substituted by a much denser, sculptural manner of painting and more contemplative and poetic subjects. His palette was for the most part reduced to the famous set of four colors: black, white, yellow ochre and red earth."

Further on, we will tell you about several pupils of Rembrandt, who managed if not to exceed the teacher, but to achieve considerable fame.

Govert Flinck (1615-1650)

We owe Flinck to "alternative" portraits of those people who are so familiar to us from the work of Rembrandt himself and his wife Saskia.

The stories were taken from two completely different contexts — biblical and ancient. In one case, the forefather Isaac mistakenly blessed the wrong one: although his first-born child was another son, Esau (the one who sold the birthright for a lentil stew), Isaac’s wife Rebekah, using the blindness of her dying husband, summed up the second son — her favorite Jacob. In another case, the seductive princess of Argos Danae, sealed in the underground copper house by King Acrisius, who fears death by the hands of an unborn grandchild, invitingly extends her hand to the lover Zeus, who impregnated her in the form of a shower of gold.

Samuel Dirksz van Hoogstraten (1627-1678)

"Samuel van Hoogstraten", we could find rare details in Rembrand’s biography by Pierre Descargues, "./recalled the difficult moments when the teacher’s exactitude plunged him into deep sorrow. With tears in his eyes, without giving himself a break, the pupil did not eat, did not drink and did not leave the workshop until he corrected his mistakes. If this was violence, it was not generated by power, but by exactingness. In fact, Rembrandt-the teacher believed that the young people who came to him were too absorbed in ready-made ideas "

Hoogstraten himself in a letter to his brother told about the wisdom that Rembrandt gave him: "When I asked my teacher Rembrandt many questions, he quite rightly replied, 'Try to put well in practice what you already know. In doing so you will, in good time, discover the hidden things which you now inquire about."

Hoogstraten painted relatively few paintings — this was due to the versatility of his interests and his reluctance to confine himself exclusively to painting. As a writer he was known no less than as an artist, and his book "Introduction to the Academy of Painting", published in Rotterdam in 1678, put Hoogstraten among the first-rate theoreticians of the XVII century (in contrast to Rembrandt, who did not devote his almost 30-year-old history of teaching a single treatise or article). So it’s no wonder, as it turned out, in one of the early self-portraits, Hoogstraten portrayed as his attributes not the palette and brush, but the pen and paper.

Nicolaes Maas (1634-1693)

However, portraits in the spirit of Rembrandt didn’t bring Nicolaes Maas fame, he became popular for his genre scenes instead, and as a portraitist he became famous only after he had refused to follow Rembrandt, but immediately began to imitate another artist — Anthony van Dyck.

Ferdinand Bol (1616-1680)

Dutch burghers with millstone collars, Old Testament heroes in turbans, women, intently bent over the books — all these recognizable Rembrandt heroes in Bol’s work are so numerous that even specialists sometimes find it difficult to determine to which of them, the pupil or the teacher, belongs one or the other painting.

Like Hoogstraten, Ferdinand Bol in the late 1640s went through the temptation to assimilate his own self-portrait to the Rembrandt’s appearance: he used such attributes as recognizable beret and precious regalia on the chest with which Rembrandt, in periods when his soul was seized with vanity, loved to decorate himself.

Gerrit (Gerard) Dou (1613-1675)

Gerrit Dou spent about three years in the Rembrandt’s workshop, but the influence of Rembrandt on his art was not too significant.

Subsequently, their ways would split: Rembrandt moved to Amsterdam, and Dou stayed in Leiden. Though it won’t stop him from becoming famous for his scrupulously and very carefully painted paintings with a smooth enamel surface. Rembrandt, in spite of the tastes of his contemporaries and the displeasure of customers, would avoid totally smooth surface more and more: he would work with thick paints, purposely gave volume to the strokes, which results in a relief surface, so annoying for the rich customers, and to get a "knobby" surface, he would add to the paints ground quartz and silicon oxide.